Why isn't female employment enough to erode patriarchy?

In patriarchal societies,

Prestigious networks (commerce, politics, religion) are dominated by men;

Men are revered as high-status, knowledgeable authorities.

(1) and (2) tend to be mutually reinforcing. When members of one group predominate in socially valued domains, they accrue greater respect. Wealth, power and specialist knowledge in turn enhance status and the capacity for ideological persuasion. Successful elites can persuade everyone else that existing institutions are entirely just.

These two structures - institutional and ideological - reinforced patriarchy for centuries. In Enlightenment Europe, men dominated commerce, science, politics, law courts, religion and media, then championed their own brilliance, while subversive women were vilified.

But then came a major engine of gender equality..

20th century economic growth was a major engine of gender equality

As theorised by Claudia Goldin, US men initially resisted their wives’ employment in order to maintain status. But this cultural preference was overcome by skill-biased technological change, which generated high-paying, culturally esteemed and psychologically rewarding skilled jobs. The Pill enabled women to control their fertility, secure higher education and build careers. As women increasingly demonstrated equal competence, gained recognition from their families, friends and co-workers, many vocally criticised sexist unfairness

Patriarchy’s institutional and ideological pillars weakened, simultaneously. Longitudinal US data shows that gender stereotypes about communion, competence and intelligence have declined.

As US women made in-roads, they pushed for recognition

The US Postal Office issued stamps celebrating past female heroes. This is crucial. Pioneers are not necessarily glorified, nor do they become ‘role models’. What matters is whether a wider movement successfully demands recognition.

Patricia Harris served as dean, professor, chairperson of President Kennedy’s National Women’s Committee, the first female African American U.S. ambassador, and the first African American woman appointed to a presidential cabinet. At her 1977 confirmation hearing, she remarked,

“If my life has any meaning at all, it is that those who start out as outcasts can wind up being part of the system”.

But it was only in 2000 - after concerted calls to celebrate minorities - that she was ideologically recognised on a US stamp.

As women demonstrate equal competence, they collectively affirm their importance

The US is not alone. My PhD explored a century of social change in Zambia, studying growing support for gender equality, encapsulated in the saying,

“banamayo kuti babomba incito sha baume” (women can do what men can do”).

In Cambodia, I similarly saw that as people migrated to cities, they saw masses of women undertaking socially valued jobs, recognised women’s equal competence, and collectively affirmed gender equality.

Support for gender equality has similarly increased in Latin America and East Asia. Based on this cross-national longitudinal research, I inferred that gender inequality was reinforced by low female employment. If only more Indian women undertook socially valued work in the public sphere, they might gain status.

But female employment does not necessarily advance gender equality

My priors were rocked by spending a month in Uzbekistan, where female employment is doubly high, yet most people still insist that wives should obey. Students, teachers, and professionals all affirmed patriarchal dominance. So I began to wonder..

Maybe paid work doesn’t necessarily advance women’s autonomy?

Putting this to the test, let’s compare attitudes in India, Indonesia and Malaysia. Female employment is far higher in South East Asia. Has this advanced equality?

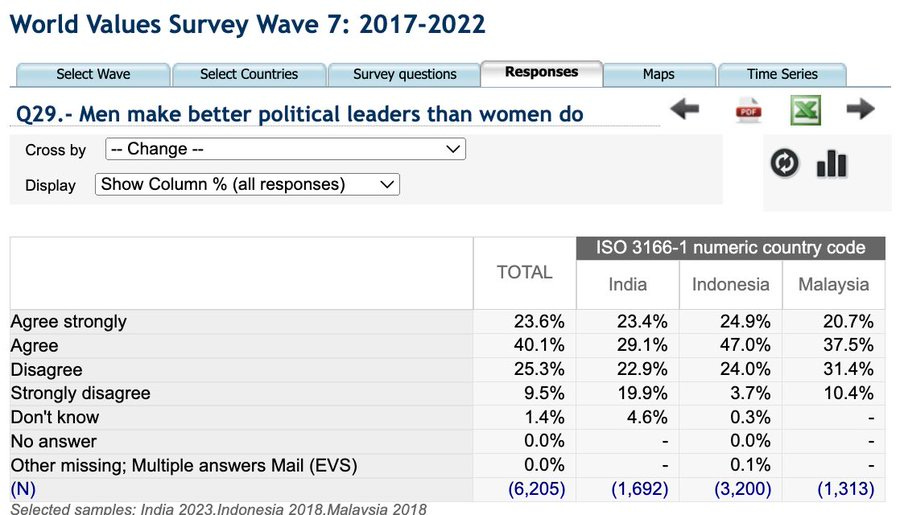

Indonesians and Malaysians actually express stronger support for male leaders.

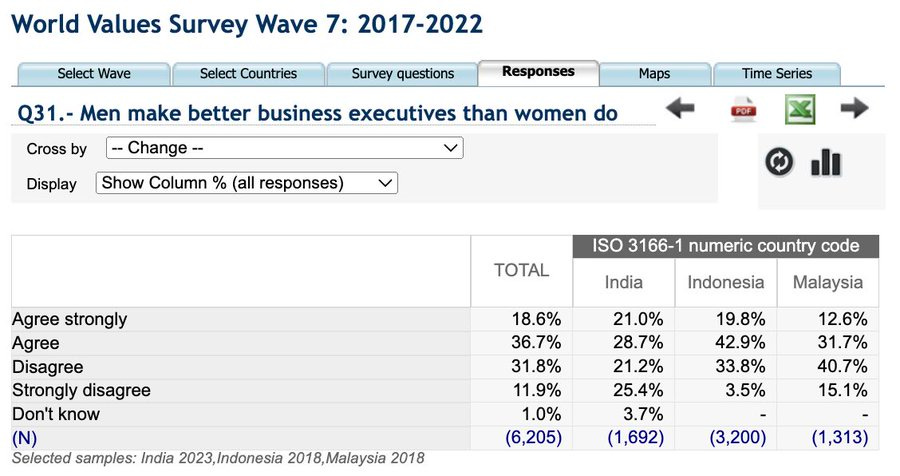

Indonesians also say that men make better business executives.

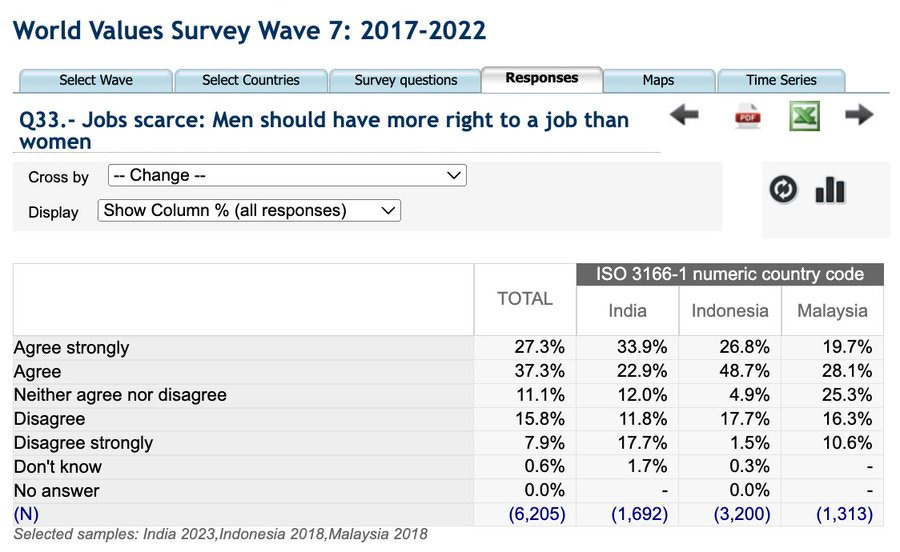

Indonesians are also more inclined to say that men are more entitled to jobs.

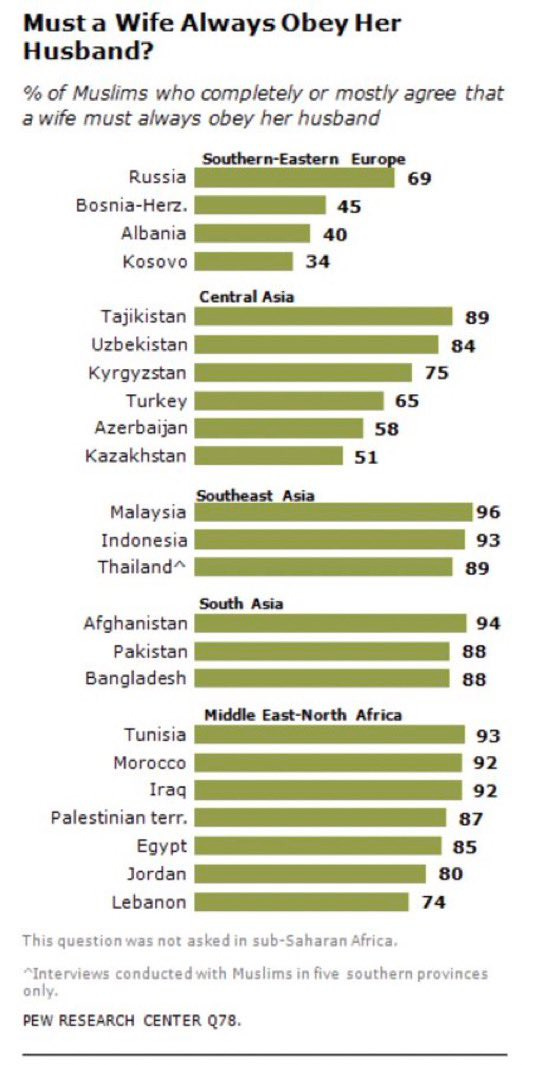

Regardless of women’s economic contributions, 93% and 96% of Muslim Indonesian and Malaysians still say they should obey their husbands. Across multiple dimensions therefore, Indonesians and Malaysians appear much more patriarchal.

No matter what women do in the workforce, they may still be deemed subordinate.

Why has employment advanced women’s status in some countries, but not others?

This is a major gap in our knowledge

My answer?

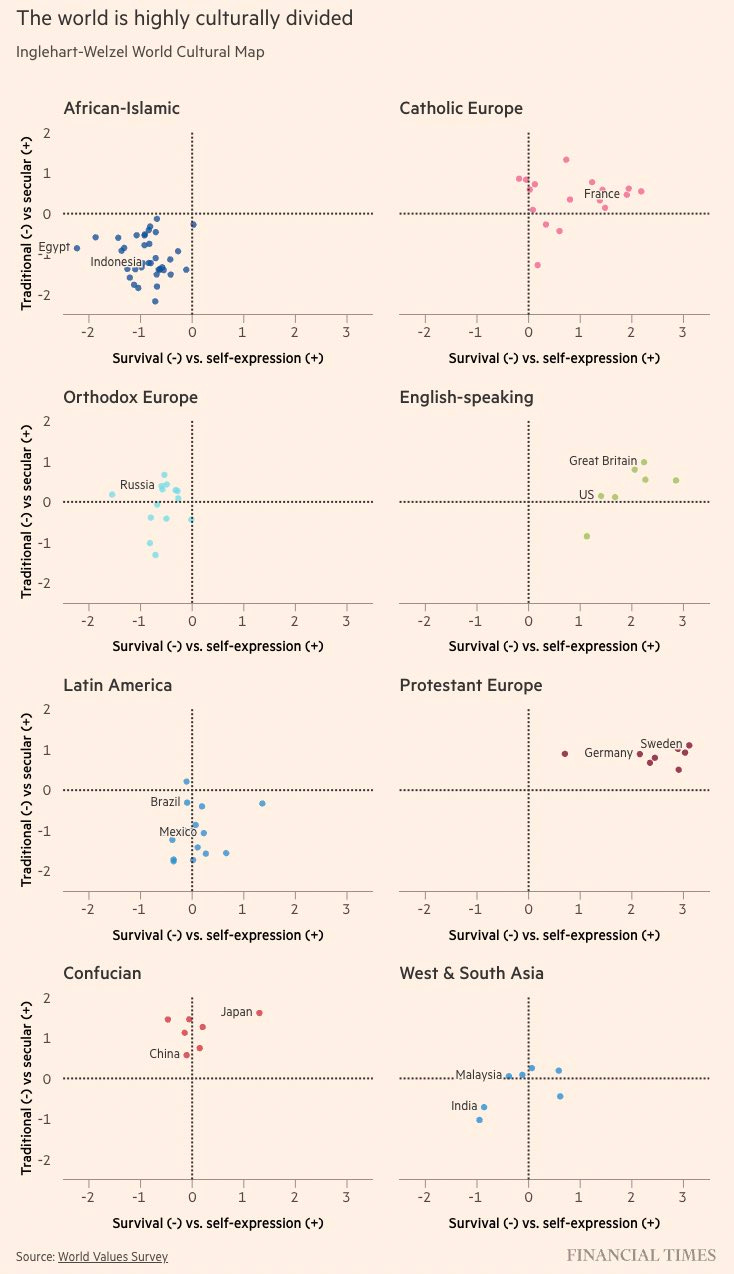

Authoritarian repression obviously inhibits feminist activism. As I have previously argued, post-communist countries tend to be especially sexist, as dissent was suppressed.

Collective harmony is sometimes privileged, over self-expression. Subversive voices are thus unwelcome. Michele Gelfand calls such societies ‘culturally tight’. Social policing, concern for wider approval, and condemnation of deviation may quieten female assertion. So regardless of women’s economic contributions, they may still be deemed low status. If feminist dissent makes people enormously uncomfortable, this discourages open discussions, and allows for the persistence of sexist discrimination. That is my theory of why South Korea has the largest gender pay gaps in the OECD.

Religion is enormously important. Faith isn’t reducible to prayer and ritual, it’s an entire way of life and system of values. Muslims generally say that a wife should obey her husband. Disagreement is more common in post-Communist countries (where religion was violently repressed). Agreement elsewhere is almost universal. This holds irrespective of female employment. 55% of Indonesian women are in the labour force, but 93% still say women should obey. These ideals have been reinforced by Saudi-funded Salafism.

So in places with (1), (2), (3), female employment can rise, but men may still be revered.

Related Posts

And check out the Smithsonian National Postage Museum’s Special Exhibition of Women on Stamps