The Global Collapse of Coupling & Fertility

Coupling and fertility are falling. In Finland, Mexico, Peru, South Korea, Thailand, Turkey and the US, both metrics point downwards. In a recent piece for the Financial Times, John Burn-Murdoch has plotted some epic graphs, on the 21st century’s greatest challenge. Drawing on my cross-cultural research and shocking TikToks, let me share what’s driving these global trends and regional differences.

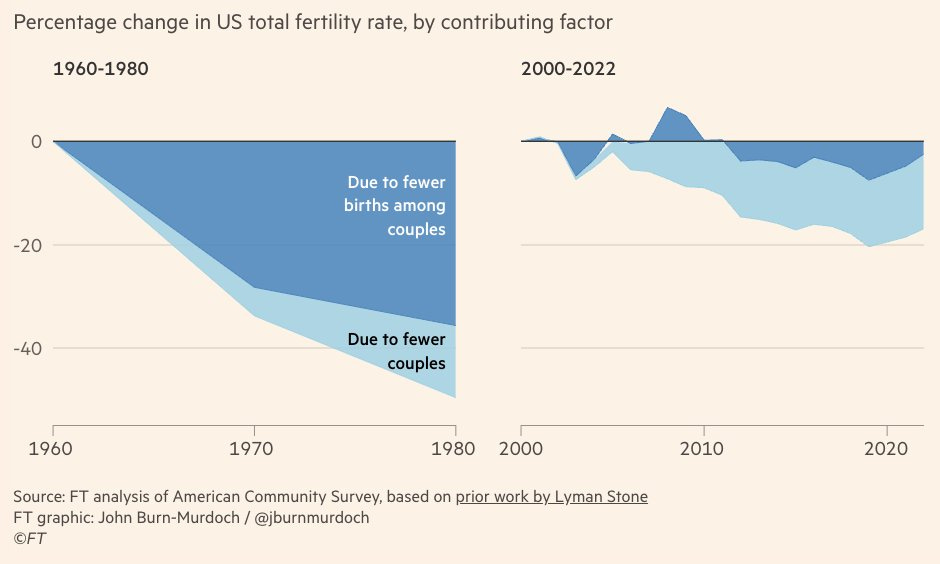

Historical declines looked different. From the 1960s, US fertility fell primarily due to fewer births among couples. In that context, baby bonuses might raise fertility. But today, the major contributing factor is the decline of coupling.

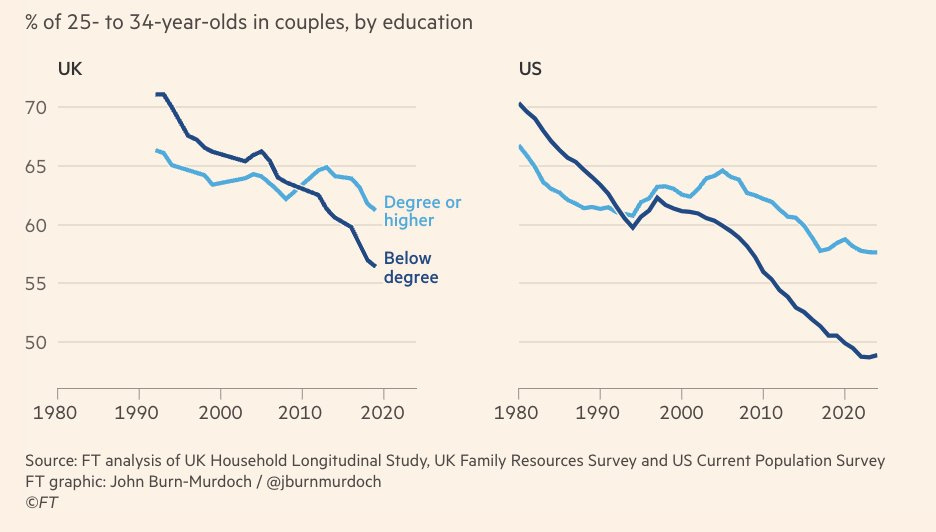

Slurs of ‘childless cat ladies’ usually target female graduates, but the real decline is happening among people with less education.

Why is this happening everywhere all at once?

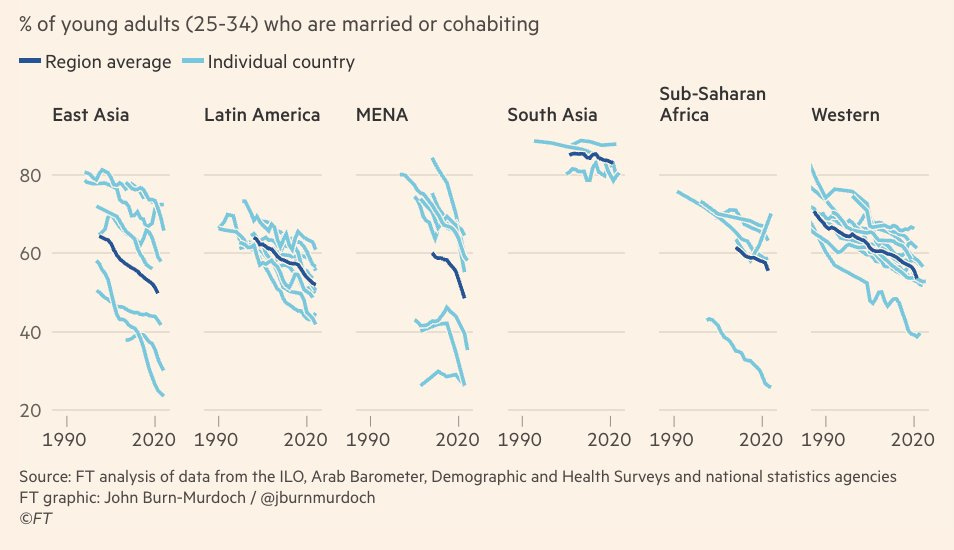

Coupling is declining across the West, East Asia, Latin America, and most severely in the Middle East and North Africa. Why?

The ‘relationship recession’ coincides with the rise in smart phones

I suggest two possible connections:

Smart phones and technology have massively improved the quality of personal entertainment, creating both distractions and conveniences. This encourages encourage home-bound isolation. As chronicled by Jean Twenge and colleagues, US teens are spending more time alone. COVID then created an exogenous shock, vastly improving the infrastructure of solitude. Working from home, without the drag of making fun banter by the water-cooler, people may not necessarily develop confidence and charisma. Instead, they become more socially anxious.

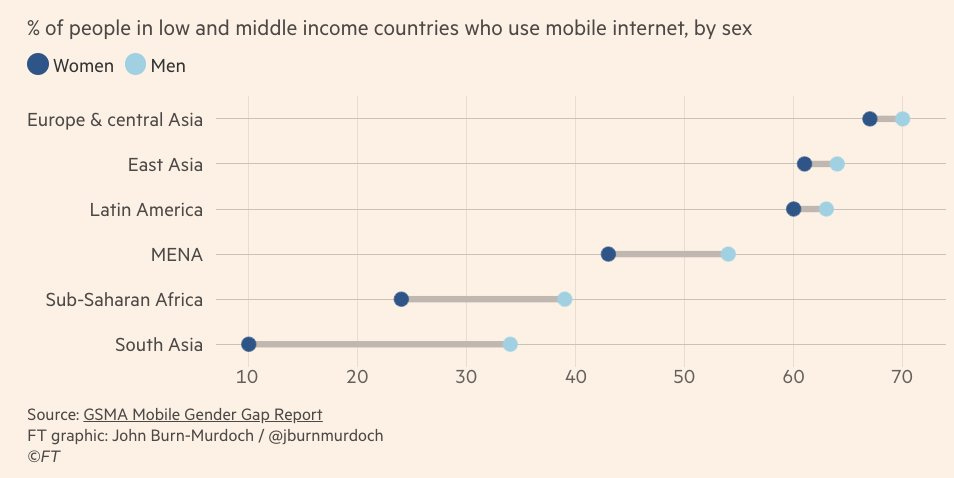

Online connectivity enables anyone in the world to peruse books, films and social media that champion gender equality. Women in Turkey, Malaysia and Mexico can ‘culturally leapfrog’ to the most egalitarian frontier. However, this process is notably asymmetric. Male compatriots may rather maintain their established status! As a result, the sexes drift apart.

Why is Coupling Plummeting across the Middle East and North Africa?

My interviews and wider surveys point to one source of friction: women becoming more progressive, while men are just as patriarchal as their grandfathers. But this is not necessarily the only factor. We urgently need more empirical research on this question.

Who do Egyptian men really adore?

“No one wants a mother-in-law. If someone is telling you about a groom, and his mother is dead, that’s always looked at as ‘lucky you!’”. Sara and I chuckled, but her observation of Egyptian marriage markets was seriously telling. Young women increasingly recognise these rigidities: demanding mothers-in-law and devoted sons.

In Arabic culture, mothers become known as ‘Om’ or ‘Umm’ followed by their eldest son's name. If a mother's firstborn is Abdullah, she becomes ‘Om Abdullah’ - a pre-Islamic custom featured prominently in sacred texts, which may have spread via conquest.

“Even when I insist on being called by my name, it’s always by the son's name. That’s the only base of her identity”, remarked Sara.

Since women are so dependent on their sons, his marriage poses a threat:

"It’s literally life threatening. “I've raised my son all my life, and this stranger comes and snaps him from me”.

To mitigate this risk, sons are often raised to prioritise their mothers. ‘Islam puts mother on a pedestal: it’s constantly about “Your mother, your mother, your mother”, explained Sara. I chipped in, quoting scripture, “Paradise lies at the mother’s feet”. She then shared an example from social media:

“There’s a crazy trend in Egypt, on the wedding day, the husband will leave the wife, and go to the mother, and give her a cake. And be totally dismissive of the bride”.

On Egyptian TikTok, you’ll see a couple of viral videos. After cutting the cake, the grooms runs to give the first bite to his happy mother, leaving the wife jilted and humiliated. These are by no means representative, but may certainly motivate caution. To quote one reply,

“If I were in the bride's position, I would have left the wedding and walked away” (translated).

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Serving your mother the first bite of cake is just the beginning:

“When people come back from the Gulf, the first thing they do is build a storey house, with an apartment for each of the children. The young brides are expected to serve the in-laws: they cook for the entire family, the unmarried brothers, the mother in law, they clean. And when the woman tries to complain, he will tell her “I married you, so you must serve my mother in law”. So it’s very derogatory..

The women know they will be treated as servants, as second class citizens”.

Women are becoming increasingly critical

In a separate interview, Hussain (48) from Cairo, independently remarked on gender polarisation:

“There’s not much progress in the male mindset, compared to the women. The women have become much more open and Western. Young women want to work, want to experience. Women are progressing - faster than the men.

Men don’t want to lose their advantage. Men don’t want to lose control. Men are still jealous and possessive” - remarked Abdullah (a manager of a large professional firm in Cairo).

“In Morocco, women will say the husband is the king. That’s why [Egyptian] men want to marry from there. They want to be the king. We believe very much in male superiority, the male should guide the family.

In the West too, men want to be king. They just can’t get it. Who wants to clean the dishes?” [we chuckle]

Egyptian men not only seek status but also female seclusion - and this reflects strong social policing. As Sara explains,

“There is a word for a guy whose female family members are non-conformist: “dayouth”. The lowest of the low. If your wife is not veiled, your immediately labelled as dayouth. If your sister, or daughter is not veiled, you’re automatically lablled dayouth. So they conform.. I only heard the word “dayouth” from 2011 with the rise of Political Islam”.

Men thus gain status through status, female seclusion, and filial devotion. Whereas women are increasingly critical.

Marriage continues to impose a rigid straitjacket, yet women are becoming more wary. This may help explain why some are opting out. As Sara explains, “This is the beginning of the realisation of the absurdity of the situation”. Indeed, Egypt is now seeing a rise in divorces.

Why are marriages high in South Asia?

South Asia has, I suggest two distinctive features:

Caste and kinship networks are secured through marriage, which remain vital for status and social inclusion. Girls are typically socialised to marry, obey their in-laws and stay put. A litany of relatives ask, “When are you getting married?” Singledom and divorce are both heavily stigmatised.

Gender gaps in smart phone ownership are especially large. As recently as 2022, only 20% of ever-married Bangladeshi women had ever used the internet. Lack of access to modern technology inhibits women’s cultural leapfrogging.

With status so heavily tied to marriage and caste, and little confidence in dissent, weddings remain a firm fixture.

The decline of coupling and fertility is the greatest challenge of the 21st century

These trends are global, but the strength of different factors may vary by region. In Western societies, where gender equality enjoys broad support, our coupling crisis may be amplified by digital isolation. Despite all its conveniences and easy enjoyment, spending so much time home alone probably thwarts social charisma and confidence. Going forwards, I’m keen to see more research on the impacts of school phone-bans.

The Middle East and North Africa face distinct challenges. Online connectivity appears to be shifting young women’s expectations and driving a disconnect. For women to choose marriage, they may want assurances of the first slice of cake.

South Asia poses a curious conundrum: as smartphone access expands and daughters become ever more educated, will families still prioritise caste-based marriages? Or might they adopt a new strategy - raising daughters for economic independence? Given how male honour remains tied to female seclusion, such transitions face significant hurdles.

How important is economics? Well, on the one hand, the convergence of men and women’s earnings enables women to be economically independent. That said, rising female employment is not a necessary condition, since fertility is collapsing across diverse economics. Even in countries where women’s labour force participation is low, and those that have endured economic stagnation, coupling and fertility are declining.

While macro-economics is not causal, it will certainly take a hit. Low fertility means a shrinking workforce, rising dependency, and reduced fiscal space. In the absence of mass immigration or an AI miracle, we will all be poorer.

Should feminists celebrate as marriage nose-dives? Well, as women ‘culturally leapfrog’ and ‘ghost the patriarchy’, men are invariably getting rejected, and denied status. I would thus anticipate male resentment and backlash.

Bravo to John Burn-Murdoch for creating these excellent graphs, demonstrating global trends and regional differences. Stay tuned for our podcast, forthcoming on the FT’s Economics Show.

Can’t wait? Check out my recent conversation with the hilarious Adam Conover: