Cultural Leapfrogging: Swiping Past Tradition

Happy 2025! Let’s start with a bang: technology and cultural change!

Imagine a young woman in conservative Konya, Turkey, whose Instagram feed is filled with globe-trotting influencers. Or a teenager in Lahore, escaping religious strictures by watching “You’ve Got Mail”. How do we explain their shifting aspirations?

Some think that cultural change follows economic development: wealth catalyses shifting values, or that expanding opportunities power female careerism. Yet my qualitative research across Asia, Anatolia, Africa and the Americas suggests a different story: the power of ideological persuasion through media.

I call this process ‘cultural leapfrogging’. Like technological leapfrogging in development economics, where nations skip intermediate stages of industrial evolution, individuals can now bypass parents and local authorities through exposure to global media. With mobile internet reaching 57% of the global population, this process is accelerating. A young woman in Malaysia does not necessarily identify with local ideas of prestige - instead she turns to “Emily in Paris”.

This narrative is perfectly consistent the wealth of evidence on social learning from parents, neighbours and local television. Now, smartphones introduce a crucial twist: content consumption is now personalised. Naturally, individuals gravitate toward media that celebrates their own status - for women in patriarchal societies, this means content championing female autonomy and achievement, while men, who benefit from existing hierarchies, seek content that reinforces their patriarchal authority. As these gendered worlds of aspiration drift further apart, a new chasm emerges.

The Technological Foundations

20th century innovations ushered in an unprecedented era of transnational learning. Print, radio, and television expanded our capacity for large-scale cultural influence, but the real revolution came with smartphones. Today’s technological connectivity has dramatically reduced the friction in transnational learning, enabling instant access to diverse media.

Internet access is now so good that when I was hiking through the Atlas mountains (that’s over 3000 metres), I ended each day by reading draft chapters of a friend’s manuscript, emailing pages of detailed comments.

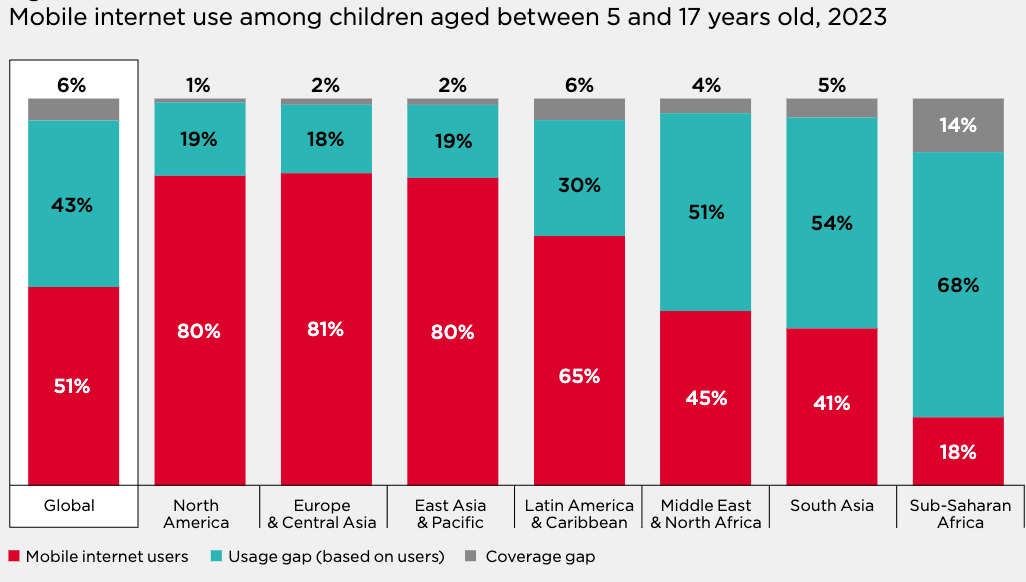

Connectivity varies by region. It is extremely high across the Americas and East Asia, while lower in Sub-Saharan Africa. In patriarchal and poor South Asia, women are far less likely to have their own mobile phone. But even this inequality has diminished.

The Mechanics of Cultural Leapfrogging

Cultural leapfrogging operates through four key mechanisms:

Any teenager with a smartphone can now binge their favourite shows, browse social media or listen to podcasts from anywhere in the world. Personal headsets leapfrog local gatekeepers or family preferences, with far greater privacy.

Watching gripping stories, viewers are inspired by charismatic influencers, admiring their freedoms, and seeking something similar.

Unlike previous waves of globalisation, smartphones (and headphones) allow for more personal choice.

Men and women may self-select into their own filter bubbles.

Technology doesn’t automatically take a side, it’s value-neutral. But humans gravitate towards content that resonates with our existing beliefs and desires. Geopolitical prestige plays a crucial role here – liberals who view the United States as aspirational may favour Hollywood productions, whilst devout Muslims might prefer content from YouTube imams, particularly those trained in Egypt or Saudi Arabia. Gender also marks a split: women may seek out stories that resonate with ideas of equality and independence.

Let me illustrate this through stories from Pakistan, Malaysia, Mexico, Egypt and Turkey.

Pakistan

Hamza’s father was violent, jealous and controlling. His mother was frequently beaten, not even allowed to go shopping for Eid. The madrasah was similarly rife with abuse, where imams instilled religious discipline with long wooden sticks.

When his father was away, Hamza and his mother found solace in romantic comedies – ‘Sleepless in Seattle’, ‘When Harry Met Sally’, and ‘You've Got Mail’. As he grew older, Hamza discovered romantic literature, becoming enchanted by ‘Jane Eyre’ and ‘Middlemarch’. This teen in Lahore, surrounded by cruelty, let his imagination run wild in stories of loving companionship. Spell-bound, he dreamed of finding his wife, and growing old together, hand in hand.

Minor hitches: crappy infrastructure and electricity cuts.

India

Mobile internet access is very new in India, especially for Indian women. Back in 2017, gender gaps in smartphone ownership loomed large. The overwhelming majority of Indian women did not have their own phones, could not necessarily choose their own media, or collectively re-write the script. Instead, they might listen or watch communally. This may have inhibited cultural leapfrogging.

But internet access is rapidly expanding, and wealthier women in cities like Mumbai, are rejecting earlier norms, as indicated by this video: “Do women need men?”. But check out the comments: men expressing backlash and resentment.

I think he sampled the most progressive women of Mumbai?

Malaysia

In Kuala Lumpur, I met Aisha, a modestly veiled 35-year-old who had recently ended a four-year relationship. The breaking point? Her partner's financial jealousy over her higher salary, manifesting in constant accusations of quarrelsome behaviour.

Jocelyn, a Chinese Malaysian, nodded in recognition – her own relationship had deteriorated after securing a better position. Joy, another Chinese Malaysian, captured the sentiment succinctly: “Men have too much ego”.

“Sometimes I wonder whether I should reduce myself…. but I don’t want to settle for less”.

Curious about their cultural influences, I asked about their favourite television show?

“Emily in Paris!” the young Chinese Malaysian women laughed in unison.

This Netflix sensation centres on a confident, stylish woman who prioritises her autonomy. The protagonist breaks off her long-term relationship when her boyfriend demands she return to America, and readily dismisses men who prove tedious or snobbish. Every storyline revolves around Emily, marking a sharp departure from Confucian ideals of female self-sacrifice.

Our animated discussion was interrupted by a man’s unsolicited monologue. We nodded politely, while he continued with a self-congratulatory lecture. None of us spoke, let alone laughed like before. Sensing the women’s discomfort, I naughtily manufactured our escape: “I’m thirsty! Joy, can you please help me get a drink?”.

Scampering away, we reconvened by the tea. Our brief exchange exposed a stark mismatch: Malaysia’s female graduates, inspired by international media, increasingly seek equality and autonomy. Many men, however, seem unprepared for these shifting expectations. This gender asymmetry, if left unaddressed, risks depressing both romantic partnerships and fertility.

Mexico

US TV has gained tremendous popularity across Latin America, particularly with the advent of cable, streaming services and social media. At a women's book club in Puebla, members enthusiastically discussed their Netflix favourite, “the Marvellous Mrs Maisel”. It profiles a young woman turning to the stage, overcoming sexism to pursue her talent as a stand-up comic.

Over on Instagram, Domelipa has amassed 24 million followers. She shares a vision of being young, beautiful, revelling in fun and freedom - without fear of censure.

All this echoes global trends: ‘Espresso’ by Sabrina Carpenter topped Spotify’s global charts, while Netflix’s 'Squid Game 2' is now No. 1 in 92 countries.

Egypt

“There’s not much progress in the male mindset, compared to the women. The women have become much more open and Western. Young women want to work, want to experience. Women are progressing - faster than the men.

Men don’t want to lose their advantage. Men don’t want to lose control. Men are still jealous and possessive” - remarked Abdullah (a manager of a large professional firm in Cairo).

“In Morocco, women will say the husband is the king. That’s why [Egyptian] men want to marry from there. They want to be the king. We believe very much in male superiority, the male should guide the family.

In the West too, men want to be king. They just can’t get it. Who wants to clean the dishes?” [we chuckle]

However, even if men and women drift apart ideologically, men still tend to run firms and institutions. Men can thus make lewd jokes with impunity. Abdullah tells me about professional friends making jokes with their assistants about rape.

“Egyptians are very playful, teasing, we like to crack a lot of jokes. And jokes could be about a woman’s body.. saying “you look nice” or “your skirt is too short”. Metoo has not reached Egypt. We are very much open about it.

“Another friend, teaching in US, Egyptian-American, he was telling me, “No means no”. I was telling him “No means try harder”.

As men restrict their wives’ employment, so as to avoid fraternisation and exploitation by lewd men, marriages may then remain hierarchical.

Turkey

Over in Konya, AKP heartland, I made a tremendous new friend. Veiled and devout, her mannerisms are the perfect fusion of Kim Kardashian and Nicki Minaj. Instantly, I knew she was plugged into Western media. Fluent in English, Ece and her friends are currently reading Sally Rooney.

Konya itself is changing. With three universities, young people come from all over Turkey, mixing without parental supervision. Cafes - once male preserves - now host young women in crop tops. As Ece explained,

“If you go to cafes, everyone is young, no will care. My friend [from Istanbul] was really shocked about the situation, like “omg it’s crazy”…

“Today, one of my friends sent me a photo, it’s ‘celebrating winter’ [She laughed at this coded description of Western Christmas decorations].

On YouTube, so many women look up to articulate, knowledgeable journalists like Nevşin Mengü. Over on Instagram, Ece’s friends watch glamorous influencers, sharing exotic adventures. “Before, you only knew your family, or your sister’s husband. Now, you can see EVERYTHING!”.

Spotify’s top streaming artists include Melike Şahin and Gülşen - who champion women’s independent desire, autonomy and pursuit of happiness. Popular anthems are then remixed on TikTok and Instagram - signalling wider acceptance.

Thanks to technological advances, the barriers to entry have been lowered. Irrespective of patriarchal gatekeepers, independent women can start their own channels, while smart phones radically expand their audience. Thus, for the first time in Turkish history, liberal women can really engage in large-scale ideological persuasion. Danla Bilic gained fame by poking fun at university students’ make-up, and now reflects on the highs and lows of past relationships.

Yasemin Sakallıoğlu, 37, with over seven million Instagram followers, jokes about domesticity - skewering patriarchal expectations that women should perform vast amounts of cooking and cleaning for religious festivals. Never aggressive or polemical, she’s gently subversive and relatable. Much like U.S. women’s magazines in the 1970s, she brings feminist ideas to a mass audience through irreverent, self-effacing humour.

Male comics are equally important for ongoing liberalisation. On Netflix, Cem Yılmaz and Hasan Can Kaya never target Islam, but rather the absurdities of tradition - family authority, sexual hypocrisy, and macho posturing. When orthodoxy becomes the butt of men’s jokes, it loses gravitas, making deviance far more acceptable.

‘Cultural leapfrogging’ thus doesn’t necessarily involve direct engagement with Western culture, but rather these ideas are repackaged by local cultural entrepreneurs, who embolden and affirm women’s quests for autonomy and pleasure. Women are no longer self-censoring to maintain respectability; they are speaking their minds, assessing intimacy with an eye on their own happiness. Back from her recent date, Ece was clearly raising the bar:

“He was very kind, but not funny. I wasn’t mesmerised. And he said, ‘you’re in business, “that’s so great for a woman”’. I thought “What the hell?”.

Inter-Generational Change

Young women are becoming much more individualistic. When Ece’s cousin’s husband turned violent, she left immediately, taking their child and was supported by the entire family.

Another relative, Zeynep, separated from her husband, crediting Ece’s influence: “I didn’t go to university, I don’t work, but I watch your social media. I really like your life, you go to Istanbul, you have a super cool life, you meet all the foreigners, you go to cool restaurants, you go on holiday"“ Ece added, “She really wanted this life”.

Even Ece’s very religious father is rapidly liberalising. Recently, he joked, “You should live your happy life in dad’s house, ‘cause you are princes, do not get married, cos you see all this trauma happening”. Fatherly love combined with his own economic success as a businessman means he is able to prioritise Ece’s welfare.

When discussing future plans, Ece shared:

“I would love to be married, it’s not really fun to live with your parents. I think I’ll move out, after 30”

“Would they accept you living alone?”

“No, but I will do it!”

“How do your friends get married? Do you need a wali?” (I asked, knowing this is common for many British Pakistanis)

“People date, like how the heck do you get married without dating?”.

Ece’s story perfectly illuminates cultural leapfrogging. She consumes Western media, embraces female independence, and inspires relatives.

Yet not everyone shares her vision. While women increasingly seek liberal freedoms, Konya’s men typically prefer to remain breadwinners. A former classmate, now engaged, seeks a full-time mother for his future children. He reportedly dismissed Ece as a potential partner for being “too feminist”. Ece’s response?

“I couldn’t care less what people in Konya think”.

This mismatch may help explain Turkey’s falling rate of marriage and fertility.

The Paradox of Personalised Culture

While earlier waves of technology accelerated globalisation, smartphones enable unprecedented personalisation. This creates an paradox: even as global media becomes more accessible, men and women’s cultural consumption may actually differ.

Women may self-select into media that champions autonomy and equality, while men might watch “Vikings” or play “World of Warcraft”. This growing difference in aspirations may inhibit couple-formation.

Looking Ahead

Technological connectivity enables cultural leapfrogging, independently of economic development. However, ability to act on new aspirations is still mediated by local conditions. Young people who travel to cities for university or work can forge their own communities, away from parental oversight. Together, peers encourage each other’s greater autonomy.

The growing mismatch between rapidly evolving aspirations and slower-changing social structures creates new tensions. As Ece succinctly put it:

“Their mother would never want me as a gelin [bride], ‘cause I’ll never ask my husband permission to go to a cafe.”

As men and women culturally leapfrog to different worlds, their aspirations drift apart from parents and local religious authorities. This may help explain why Korea, Turkey, Mexico and Iran all see plummeting rates of marriage.

Thank you to all my wonderful readers.

Wishing you a wonderful new year.

Looking forward to learning from you all.

Thanks Alice, another fascinating insight. I just wonder how we could reconcile *for the lack of a better word* men and women?

Yes, how do we help shift young males' ideals? Why aren't they changing as well?