Cultural Leapfrogging - Turkish Style

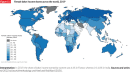

‘Gaslighting’, ‘love-bombing’ and ‘toxic relationships’ have surged in online searches across Turkey. Through interviews in Istanbul, Ankara, Konya, Midyat, Mardin, and many patriarchal countries, I began to see why: many university-educated women are ‘culturally leapfrogging’, jumping to the egalitarian frontier.

But this pattern is far from universal. Why has cultural leapfrogging been so rapid in Turkey, why do young men often remain more conservative, and what does this mean for coupling?

Turkey’s Cultural Fist-Fights

For over two centuries, Westernising reformers have clashed with social conservatives over authority, women’s visibility, and autonomy. Still today, male honour remains tethered to female seclusion. Even online, Turkish men have very few female friends. Ideals of gender segregation help explain why - despite economic growth, soaring education and falling fertility - only 36% of women participate in the labour market. Men continue to dominate state power, comprising 80% of parliamentarians.

After the 2001 economic crisis discredited secular elites, Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) rose to power - blending market reform with Sunni revivalism. Yet Turkey continues to struggle with weak business dynamism and high inflation. The AKP maintains its grip partly by favouring cronies and punishing dissent: jailing opponents, curtailing competition, weakening judicial independence, and replacing university rectors with loyalists.

But while the AKP maintains support among older voters, younger cohorts appear to be experimenting with alternatives.

4 Drivers of Cultural Liberalisation

Turkish liberals benefit from four forces:

First, when a governing regime fails to deliver, its ideology often takes a battering. Acemoglu and colleagues find that unsuccessful democracies lose support, and I suggest this holds for governing ideologies more broadly. Citizens don’t just lose faith in the ruling party, they also lose faith in its underlying mantra - whether that’s communism, progressivism etc. Since Turkey’s AKP has been in government since 2002, and is widely blamed for economic mismanagement, Sunni orthodoxy is also losing favour.

Second, compared to neighbouring Muslim countries, Turkey always had a stronger support base for secularism. Today, only 41% of Turkish parents cite ‘religious faith’ as an important quality for their children. Whereas in Egypt, 82% underscore this priority and are much more insistent on ‘obedience’. The Egyptian school system also provides many more hours of religious education.

Third, Turkey has seen skyrocketing university enrolment - from 1.7 million students in 2008 to over 4.1 million by 2020. Away from home, young people are socialising more freely, carving their own spaces. Female graduates are also more likely to be employed.

Fourth, female graduates in big cities are increasingly engaging with progressive Western values. Smart phones and cheap data mean they can circumvent parental surveillance and national broadcasters, then gravitate to channels that validate their aspirations. On Instagram, TikTok and Spotify, liberal women can speak and be heard. I call this ‘culturally leapfrogging’.

Just as artists once flocked to Paris - the epicentre of prestige in the 19th century - and repackaged prestigious styles for domestic audiences, Turkey’s feminist entrepreneurs are re-imagining female status, happiness and autonomy. They are asserting their own prerogatives, reassessing intimacy and prioritising their own happiness - to large online audiences. For the first time in Turkish history, liberal women can really engage in large-scale ideological persuasion. Their weapons of choice? Comedy, music, and glamour - fun, aspirational, online social-bonding.

Digital Footprints

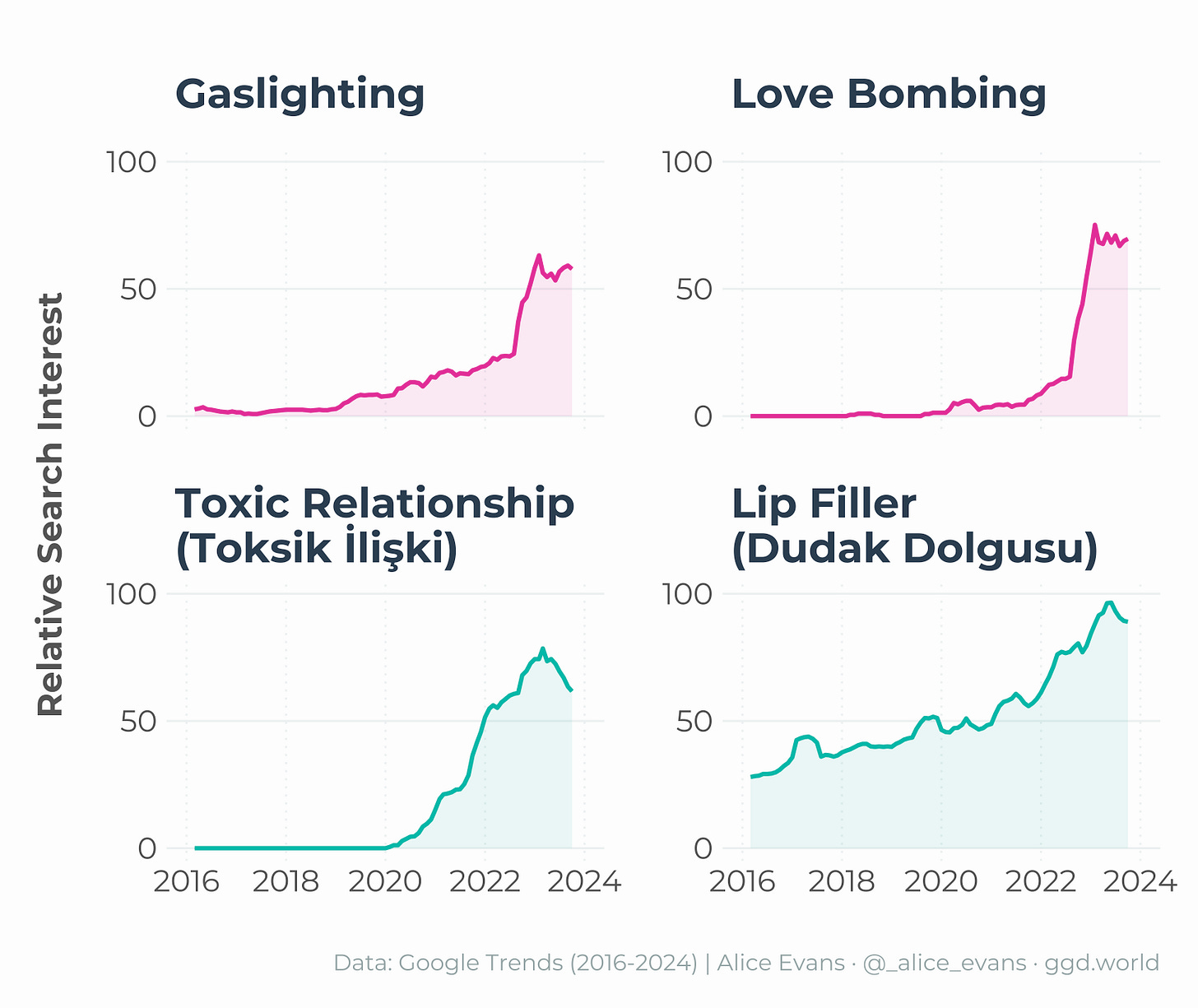

Google Trends data helps us triangulate surveys, which are often irregular, marred by non-responses and social desirability bias. For example, some may report daily prayer, but nonetheless skip a few.

Searches for ‘prayer times’ suggest the extent to which Muslims incorporate religiosity into their daily life, by dutifully checking the appropriate times for Fajr (dawn), Dhuhr (midday), Asr (afternoon), Maghrib (sunset), and Isha (night).

Analysing Google Trends, I can visualise Turkey’s regional heterogeneity. In Istanbul, locals are 2.4 times more likely to search for ‘Tinder’ relative to ‘prayer times’ (namaz vakitleri).

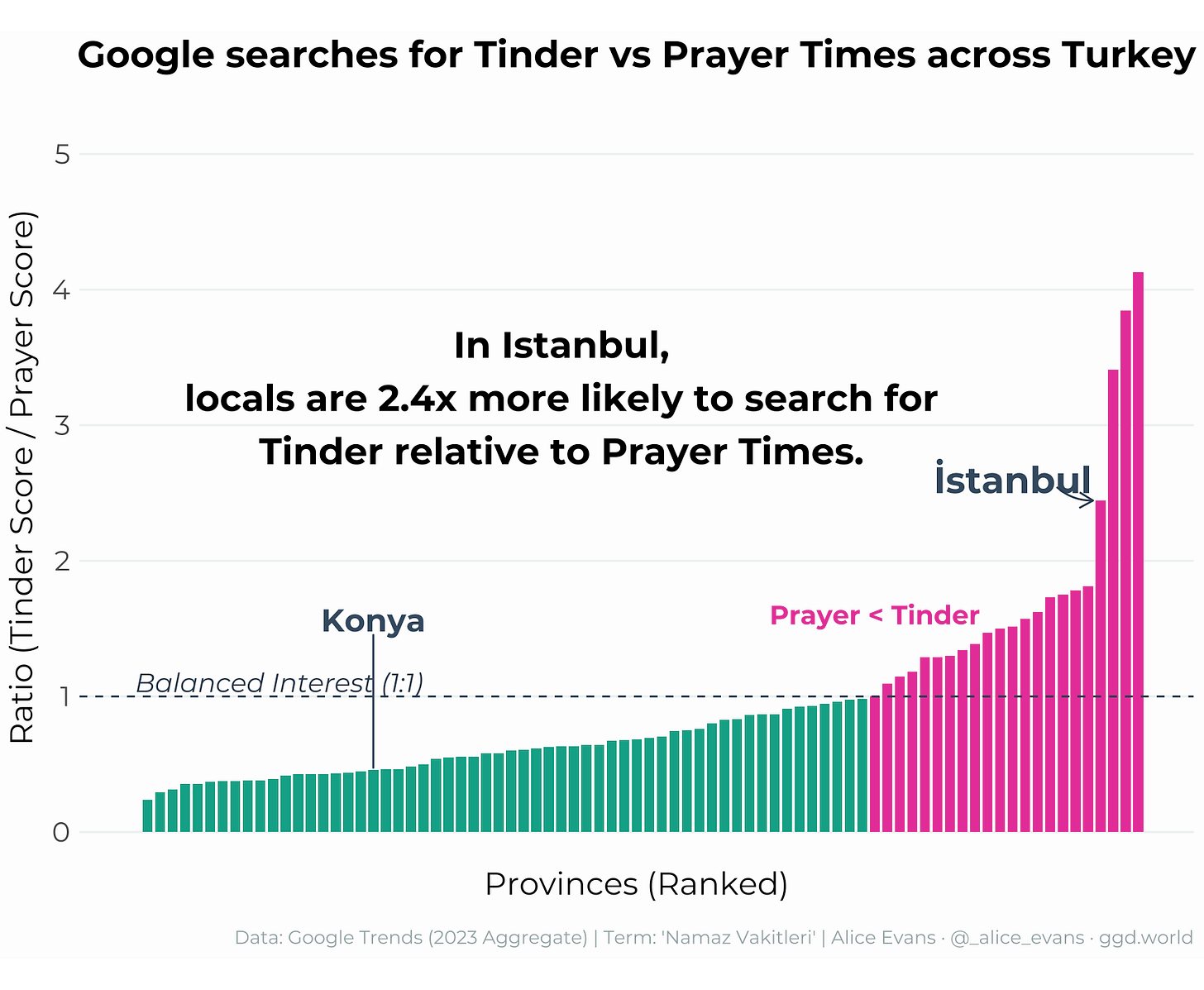

Reflecting growing embrace of US norms, searches for ‘ADHD’ and ‘lip filler’ have spiked - in both Istanbul and Konya. As we spend more time online, our feeds and algorithms, rather than neighbourhoods, play a growing role in shaping cultural expectations. And this is entirely consistent with my qualitative research…

Konya

In Konya, I was introduced to a young hijabi, yet within five seconds of meeting, I instantly knew she was plugged into Western social media. Her gestures gave the game away - fingers clicking like the supremely confident Nicki Minaj. Sassy, astute and assertive, Ece became a great friend, generously helped me interview a range of people across Konya.

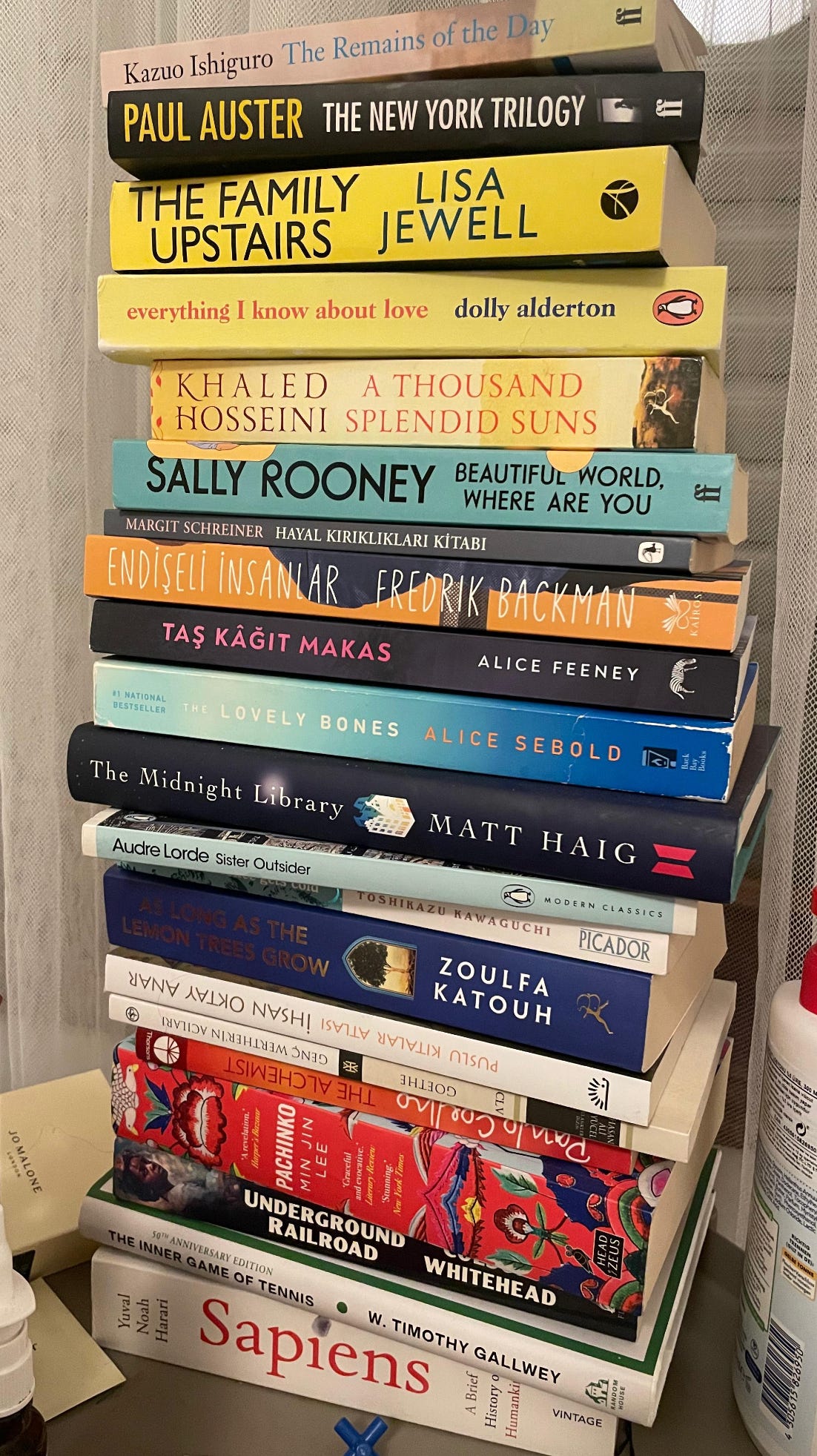

Ece’s friends - fluent in English - have formed a bookclub, stacking their shelves with Sally Rooney, Dolly Alderton, Virginia Woolf, Rebecca Kuang, Gabrielle Zevin, and Kazuo Ishiguro. These novels portray lives that are so radically different from that of their mothers and grandmothers. Instead of enduring abuse, hierarchy and domesticity, they are continually choosing protagonists who contest claims to power, while re-evaluating intimacy. Love, friendship, and even family ties are constantly open to scrutiny: “Is this actually good for me?”. Women’s desires for recognition and pleasure are cast as entirely legitimate. That may sound mundane to Western readers, but in central Anatolia it is absolutely radical.

With three universities, young people come from all over Turkey, mixing without parental supervision. Cafes - once male preserves - now host young women in crop tops. As Ece explained,

“If you go to cafes, everyone is young, no one will care. My friend [from Istanbul] was really shocked about the situation, like “omg it’s crazy”…

“Today, one of my friends sent me a photo, it’s ‘celebrating winter’ [She laughed at this coded description of Western Christmas decorations].

Male Comics

When I study world history, I realise that cultural liberalisation has usually been spearheaded by men - contesting strictures, legitimising dissent. This isn’t to diminish women’s contributions: it merely reflects the reality of patriarchy: men exercise greater authority and act as gatekeepers.

Comedy is a powerful solvent. Laughter triggers endogenous opioid release, forging social bonds. We relax, connect and feel that we’re all in on the joke. In that moment, it becomes easier for relatable and charismatic figures to broach taboos and persuade their peers.

When orthodoxy is mocked, it loses gravitas. Sacred tenets are pulled off their pedestals and deviance becomes more acceptable.

On Netflix, Cem Yılmaz and Hasan Can Kaya mock the absurdities of tradition - family authority, sexual hypocrisy, and macho posturing. While they never target Islam itself, satire is nevertheless a powerful weapon of subversion.

Mocking the Patriarchy

Marshalling this same weapon - irreverent comedy - women have been sharing their own ideas. Yasemin Sakallıoğlu, 37, with over seven million Instagram followers, pokes fun at women’s never-ending drudgery, cooking and cleaning for religious festivals. As a middle-aged mum, she’s extremely relatable - never aggressive or polemical. Much like U.S. women’s magazines in the 1970s, she brings feminist ideas to a mass audience through irreverent, self-effacing humour.

While some economists maintain that women’s low employment in the Middle East, North Africa, Anatolia and South Asia is due to care work, Yasemin Sakallıoğlu is rocking our priors. Patriarchal societies that idealise female domesticity are highly effective in ensuring women perform more housework.

Over on Instagram, femininity is being redefined, with glamorous Turkish influencers chronicling their exotic adventures. Spotify’s top streaming artists include Melike Şahin and Gülşen, who champion women’s independent desire, autonomy and pursuit of happiness. Popular anthems are widely remixed on TikTok and Instagram, signalling wider acceptance.

Beyond beats, banter and lip filler, many Turkish women also look up to articulate, knowledgeable journalists, like Nevşin Mengü. As Ece remarks from Konya, this connectivity shows a whole new world of possibilities:

“Before, you only knew your family, or your sister’s husband. Now, you can see EVERYTHING!”.

In a country where a third of women have experienced domestic violence, viral terms like ‘gaslighting’ name harms and help legitimise exit.

Bodies and Backlash

In societies where women’s bodies are a dangerous source of ‘fitna’ (moral corruption), they are encouraged to hide their bodies and cover up:

“I was constantly ashamed of my body. I felt like my body was not my own. When I was going through puberty, I was constantly told to cover up, to wear bigger clothes, to shut my legs. My father made me feel so disgusting. And this affected my sexual relationships, because I felt like my body was not my own” - Yildiz, Istanbul.

Staying in Istanbul, I joined a local gym, yet rarely saw any women. Asking more broadly, many expressed extreme discomfort. Here, the Turkish Women’s Volleyball team has been catalytic! In 2023, they won the Women’s European Volleyball Championship, becoming a major source of national pride (and attention). Sportswomen demonstrate their strength and agility, casually wearing shorts. But this has stirred backlash. After photographs circulated of Ebrar Karakurt embracing another woman, online bullies came out in droves, with one Islamist newspaper calling her “a national shame.”

In 2021, when the team was competing in the Summer Olympics in Tokyo, a prominent preacher sharply criticized the team for not adhering to his conception of how a Muslim woman should behave. Preacher Ihsan Senocak, with 1 million followers on Instagram, blasted condemnation:

Cultural fist-fights continue. A spokesperson for Turkey’s volleyball federation spoke out in her defence, praising her “spirit of a fighter to represent her country”, adding “Everyone’s private life concerns them only. All the rest is hokum.”

Ghosting the Patriarchy

Social media is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it has enabled Turkey’s female graduates to leapfrog towards egalitarianism. But persuading their male peers remains hard, because many young men appear to be gravitating towards icons that affirm their own status. In 2022, searches for Andrew Tate surged in both Istanbul and Konya. Interest in Menzil - a conservative Naqshbandi Sufi community - is often even higher.

Smartphones may deepen separation - especially in societies where men and women already keep their distance. As attention shifts to hyper-engaging apps, face-to-face connectivity may decline. Over time, this makes it harder to build new friendships, networks and personal charm. Yet if society liberalises such that young people can choose their own partners, selecting for companionship, then weak interpersonal skills create a real barrier to coupling.

Since the early 2000s, Turkey’s marriage rates have fallen, divorce has more than doubled, and fertility has dropped to 1.5. Last week, Ece went on a first date but was distinctly unimpressed:

“He was very kind, but not funny. I wasn’t mesmerised. And he said, ‘you’re in business, “that’s so great for a woman”’. I thought “What the hell?”.

While he was trying to be supportive, Ece found his approach antiquated and patronising. “Thank u, next”, I joked in reply (rightly anticipating one of her favourite songs). Thus even if Turkey’s young female graduates struggle to shift electoral outcomes, they are increasingly saying ‘no’ in their personal lives.

Will Cultural Leapfrogging Go Global?

So will TikTok catalyse worldwide secularisation? Not necessarily. Cultural prestige often tracks perceived political competence. When religious regimes falter, the pews tend to empty - as in Spain after Franco or Chile amid Catholic sex scandals. But where secular elites are blamed for corruption and economic stagnation, religious movements can harness grievance and present themselves as purer, more just alternatives - as in Egypt in the 1970s and 2010s, or Bangladesh’s Jamaat today.

Social media does not determine the direction of cultural change; it amplifies a raft of anti-establishment voices, who then battle to present a more alluring alternative.

Methodological Note

On Tinder versus Prayer Times. Each province’s bar shows the ratio of its Google Trends search index for Tinder relative to its index for Prayer Times (’Namaz Vakitleri’), with both terms independently scored by Google based on search concentration rather than raw volume.