Choice of college major is a major driver of the gender pay gap. This accounts for a whopping 63% of the entry pay gap for college graduates in the US (and 51% in Italy). Young men are consistently choosing fields of study that lead to higher earnings.

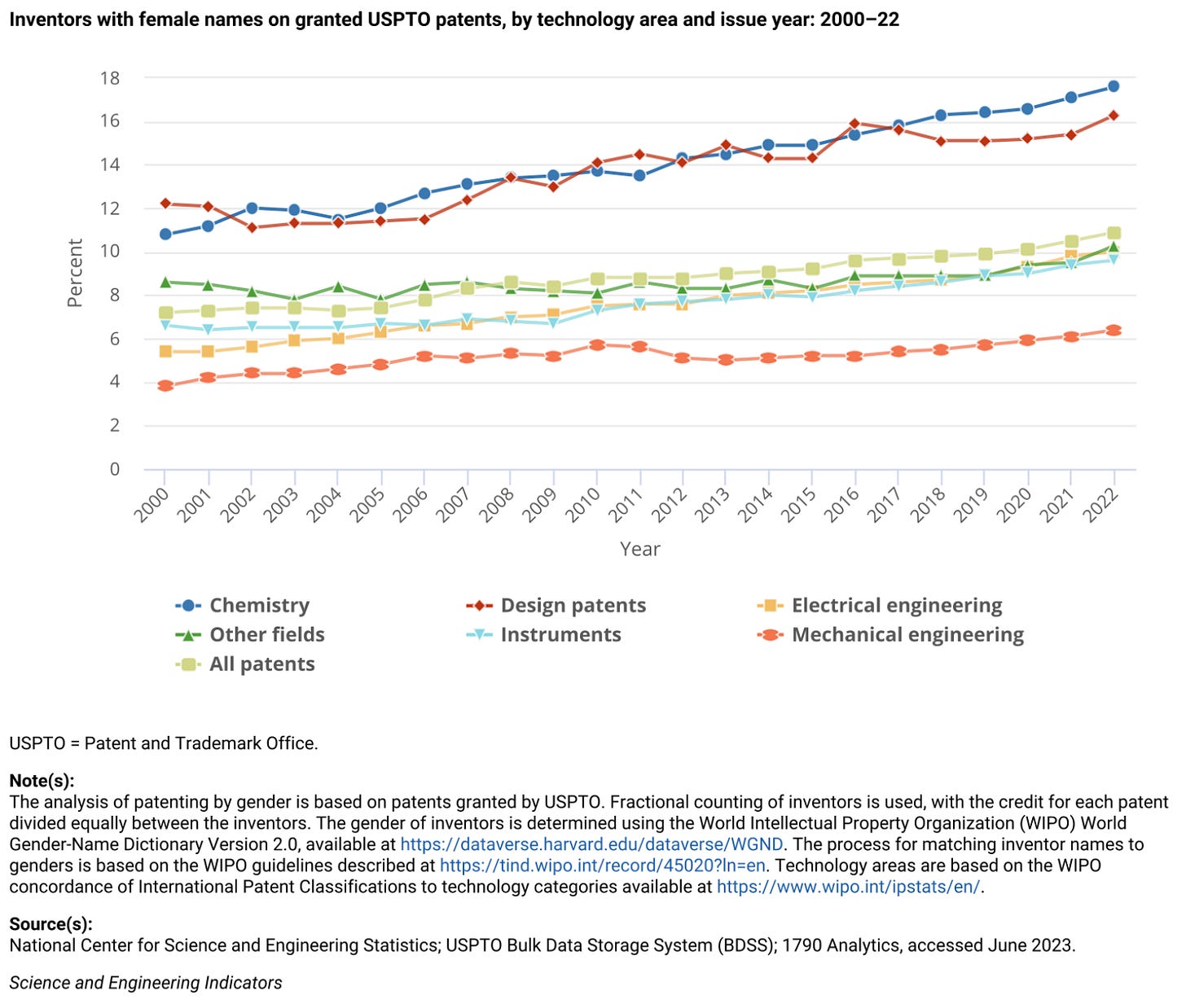

Concerned about these disparities, many have tried to encourage women into high-paying sectors, like STEM. Despite these initiatives, Engineering remains overwhelmingly male. Why aren’t more women pursuing lucrative careers?

Before we dig into an awesome new econ paper that might just crack this code, let’s play a quick game. What’s your best guess about what's really driving these choices?

Profit vs Purpose

Vanessa Burbano, Nicolas Padilla, and Stephan Meier offer a fresh perspective on this puzzle in their new paper published in the American Economic Journal. They explore an overlooked factor: the search for meaning at work.

They distinguish between two types of career-related meaning:

Meaning from social impact: The effect one’s job or organisation has on society or the environment.

Meaning from non-social impact: A sense of accomplishment or pride in one's work, unrelated to social impact.

To investigate gender differences in preferences, the researchers employed:

Cross-country Survey: Data from about 110,000 individuals across 47 countries.

MBA Student Study: A choice-based conjoint analysis with a full cohort of MBA students at a top US business school, tracking their behaviour over two years.

In this blog, I’ll discuss their results and share some unorthodox reflections about how to address the obstinate gender pay gap. Spoiler: it’s about changing ‘bad vibes’.

Cross-Country Differences in Preferences for Meaning at Work

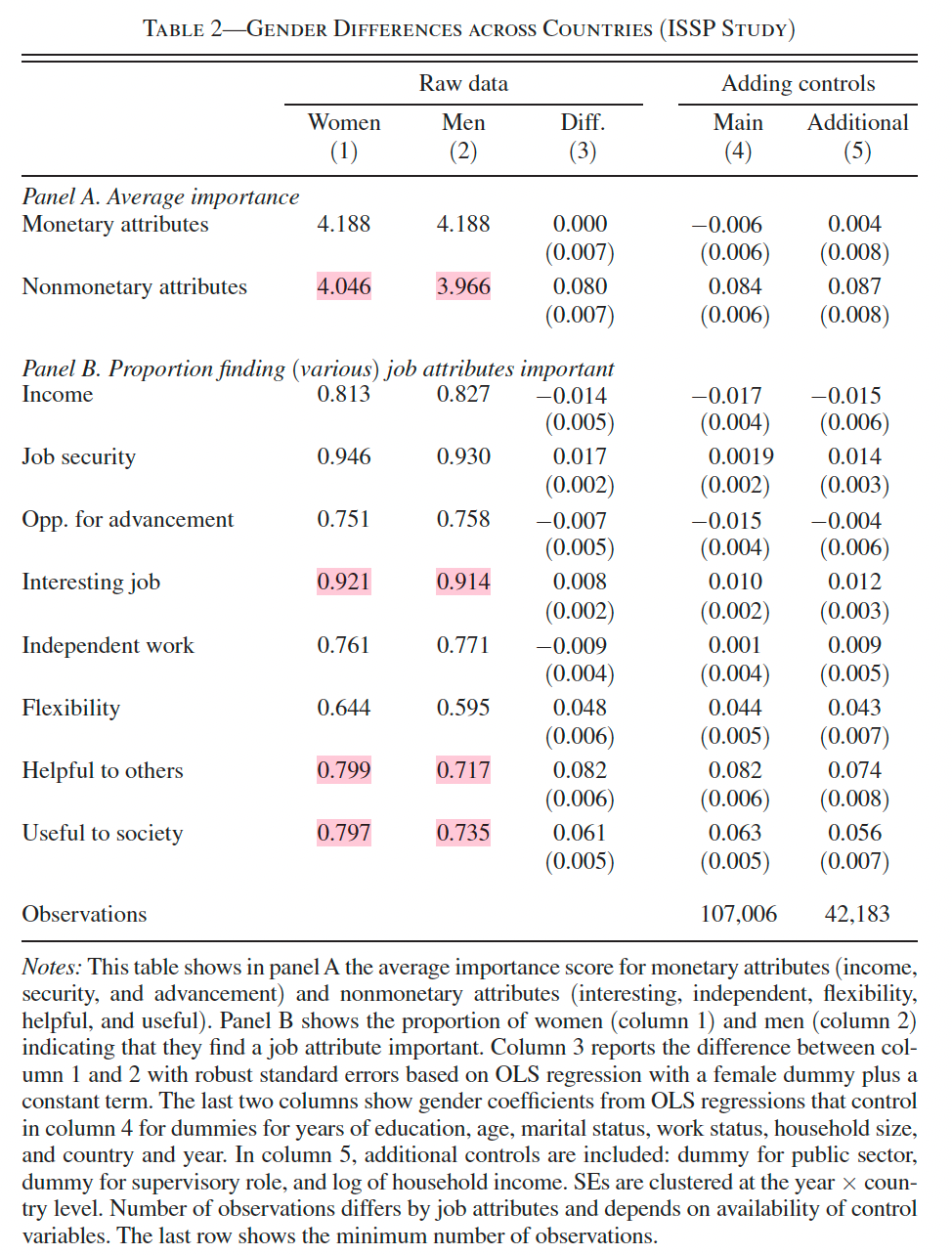

The International Social Survey Program (ISSP), a treasure trove of data covering approximately 130,000 individuals across 47 countries. This dataset spans four waves of time (1989, 1997, 2005, and 2015), providing a rich, longitudinal perspective.

Methodology:

Survey Questions: The core of their analysis revolved around questions about job attribute importance. Participants rated various job characteristics on a 5-point scale from ‘Very important’ to ‘Not important at all’.

Data Preparation: They focused on participants aged 16-65 and rescaled answers so higher values indicated greater importance.

Statistical Analysis:

Dummy variables for each job attribute, indicating whether it was considered 'Very important' or 'Important.'

OLS regressions to control for various factors (age, education, public/private sector/ household income), included country fixed effects etc.

Country-specific gender coefficients were plotted against log GDP per capita.

Finally, they examined how gender differences varied by education level using interaction terms between gender and education group dummies.

Women placed a slightly higher value on helping others and being socially useful

Both genders express a preference for interesting work that provides autonomy.

The gender difference is larger when it comes to flexible working hours.

Bigger still is the gender difference in whether the job is helpful to others or useful to society. The share of women who say they value jobs which help others say is 8.2 percentage points higher than that of men.

This gender gap in preferences was larger in more developed countries.

These gender differences also became more pronounced among people with higher levels of education

Study 2: MBA Students and Real-World Choices

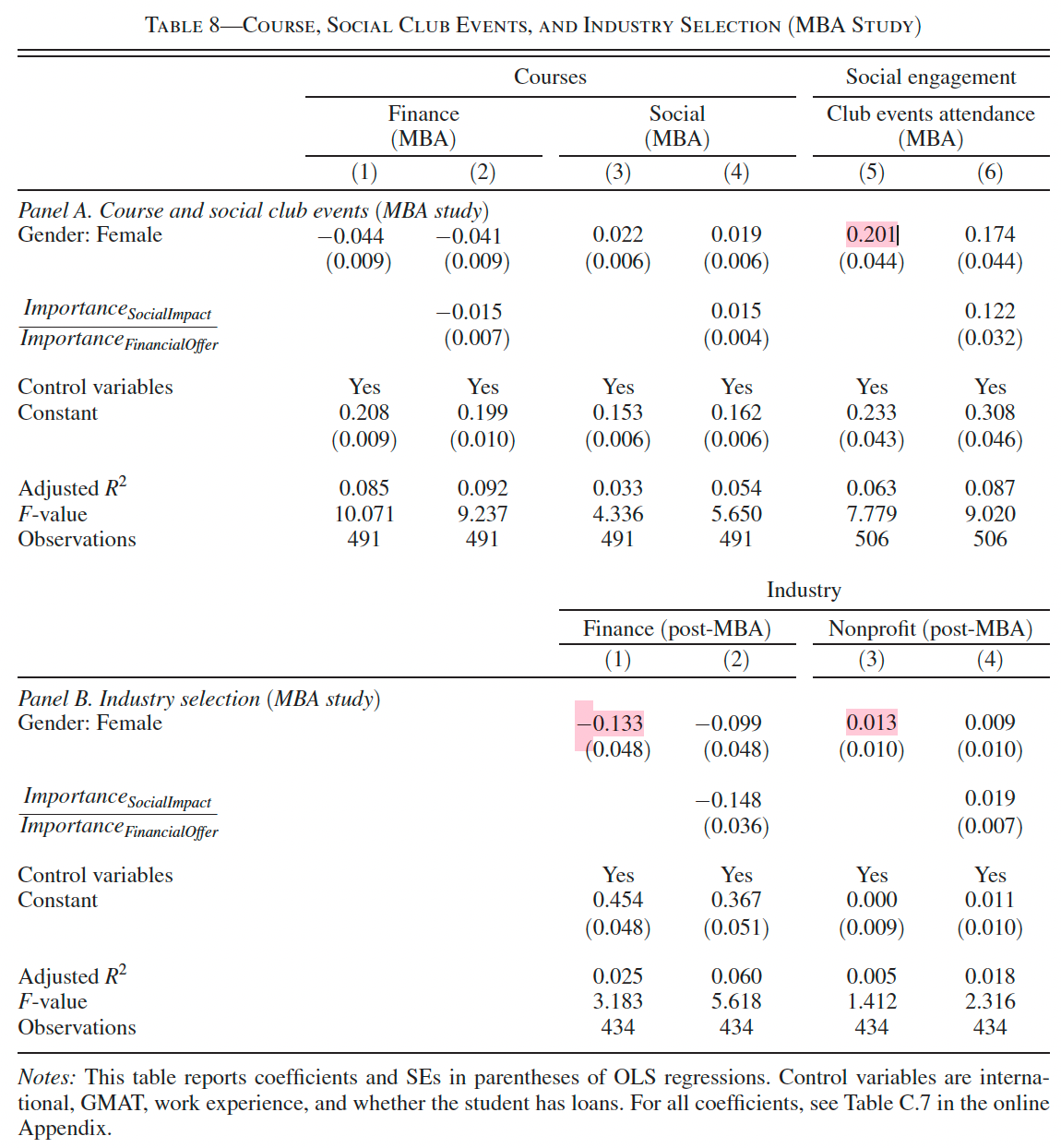

Burbano and colleagues then conducted a choice-based conjoint survey with an entire entering MBA class at a top US university. This is a good study, since they are already partly selecting for financial ambition.

Students were asked them to choose between hypothetical jobs, which varied by financial offer, record on Corporate Social Responsibility, impact, flexibility, and prestige. Each attribute had 2-3 levels (e.g., financial offer: $135,000, $150,000, $165,000).

48% of men vs. 32% of women were finance-motivated

The researchers found significant differences in how men and women valued job attributes, relative to financial compensation.

Women placed far greater value on Impact, Flexibility, and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). The gender difference is most pronounced for whether the potential employer is socially responsible.

This gender difference is probably a lower bound, since MBAs select for financial ambition.

Women students were subsequently more likely to take socially-oriented courses and less likely to pursue finance careers.

Burbano and colleagues leveraged the university’s administrative data to track students’ course selections, student clubs, and subsequent careers. By incorporating initial data on preferences, they can better explain behavioural outcomes, such as:

‘the proportion of female students going into the finance industry post-MBA is about 13 percentage points lower than that of male students’.

Industry placement has major financial implications, as the authors explain:

‘Whereas a median MBA student (at the university of our sample) who goes into investment banking receives $200,000 as a starting salary, the equivalent MBA student going into nonprofit, education, or government is paid less than $120,000’.

That’s a hit! But it’s also a good example of how educated women in wealthy countries can pursue work that they consider meaningful, yet still earn high salaries. So this may explain their cross-country finding that gender differences increase with GDP.

These findings track with my own qualitative research

Earlier this year, I got chatting to a young female student in Hong Kong. She’s eager to challenge social injustice and make documentary films about marginalised groups. Across the world, female students often tell me they want to ‘make a difference’.

Between 2016 and 2019, I conducted a massive study on activism for corporate accountability in global production networks. Interviewing campaigners and politicians across Europe, including France, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, Spain, the Netherlands, and United Kingdom, I noticed a significant presence of women among the activists, all driven by a desire to improve workers’ rights and prevent environmental degradation.

My own journey reflects this broader trend

At 15, I was greatly affected by a trip to South Africa, Lesotho, and Mozambique. After playing football with local children and seeing slums, I couldn’t stop crying. This was my first encounter with poverty and it profoundly shaped my career. While my brother went into Finance, I specialised in International Development, and now teach in the Political Economy of Development. Peter Singer’s books were also catalytic: I became concerned about non-human animal suffering and turned vegan. This anecdotal divergence mirrors the global pattern observed by Burbano, Padilla and Meier.

The Honour-Income Trade-Off

Through my globally comparative research, I’ve leant that individuals have differing preferences when it comes to earnings. For example, in Israel, only 55% of Haredic men in Israel work, because they highly value piety.

In my paper on ‘How East Asia overtook South Asia on Gender’, I emphasise the ‘Honour-Income Trade-Off’, highlighting that not everyone is equally driven by material rewards. Where male honour depends upon female seclusion, female employment remains low.

To highlight two polar extremes, Hong Kong’s Lunar Festival celebrates wealth, while Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan champions ‘honour of faith’.

What does this teach us about gender?

Burbano, Padilla, and Meier's careful study offers valuable insights into women's career preferences, revealing that income maximisation isn’t always the primary goal. This aligns with Ingrid Haegele’s compelling research in Germany, which found that junior men are more likely to apply for promotions, primarily due to a greater desire for team leadership. Combined, these findings suggest that gender gaps in pay and leadership may partly reflect women’s preferences.

The Purpose-Profit Trade-Off

Within the world of finance - often seen as a testosterone-fueled arena - women are carving out their own niche. They’re especially prominent in Environmental and Sustainable Finance. Take

Catherine Buan (Asana’s Head of Investor Relations, Sustainability and ESG Reporting);

Celine Herweijer (HSBC’s Group Chief Sustainability Officer), and

Stephanie Maier (GAM Investment’s Global Head of Sustainable and Impact Investment).

These women exemplify a growing trend of professionals successfully combining profit-driven work with broader societal impact.

This observed trade-off echoes Claudia Goldin’s seminal analysis of the gender pay gap. Goldin argues that women often prioritise job flexibility, but such positions typically offer lower earnings. Increasing pay for flexible work has proven crucial in narrowing the gap, as evidenced in pharmacy.

Now, apply this principle to ‘job purpose’. Women seem drawn to meaningful, socially responsible roles, but these often come with a financial penalty. Could addressing this disparity be key to further progress?

Looking ahead, these gender-based preferences might become even more pronounced. Young women are getting more progressive than a Portland coffee shop. Imagine a young activist staging a roadblock then joining Shell. Unlikely.

Effective Altruists pursue a third option: maximise earnings and give generously.

Are young women accurately assessing a company’s social impact?

17-year-old college applicants might underestimate the power of STEM. While Amnesty International obviously appeals to progressives, it’s possibly worth celebrating massive advances in biochemistry, pharmacology and public health:

Kati Kariko’s work on mRNA vaccines averted millions of deaths;

Tu Youyou won the Nobel Prize for discovering a novel therapy against malaria, a disease that kills millions of children;

Jenna Forsyth discovered that adulterated turmeric in Bangladesh was causing lead poisoning. An amazing national campaign then got lead out of spice, with huge implications for child health.

And let’s not forget Alice Evans!

Born in 1881, she investigated bacteriology in milk, and led to the pasteurisation of milk in the US in 1930. She was the first woman president elected by the Society of American Bacteriologists.

Changing Bad Vibes, Celebrating Public Goods

Here’s the nuance. The conventional approach to getting women into STEM has been to celebrate pioneering women, like Kati Kariko and Tu Youyou. But Burbano et al’s study with MBA students suggest that women are shunning toxic firms.

This indicates that changing occupational sex segregation isn’t just about celebrating individuals, but transforming the image of entire industries.

Now, women aren’t stupid. You cannot woke-wash British Petroleum. So, if women are still shunning Oil and Gas, we should not necessarily perceive it as an inequality.

That said, many sectors’ social impact may be under-appreciated. If your elderly loved ones survived COVID, it’s possibly due to vaccines. Biochemists saved millions of lives. Yet in the U.S., Big Pharma is widely vilified. This demonisation may have turned progressive young women away from pharmaceuticals, too disgusted and ashamed to tell friends that they’re working ‘for the enemy’.

Agricultural advancements also have tremendous potential. Famine currently looms over North Darfur, while much of Sub-Saharan Africa suffers from low agricultural productivity. If African women pioneered a drought-resilient crop, they would radically reshape the continent’s future.

College departments and companies could help change the ‘vibes’, demonstrate their social impact. Macro isn’t just maths, it’s about inequality. Computer science departments could showcase how coding can be re-wired for the social good. By emphasising positive impacts, recruiters might attract women with purpose!

Let me leave you with this. The Enlightenment was led by groups of scientists and technicians collectively celebrating innovations. Can firms’ attract female innovators by celebrating genuine contributions to the social good? And can the wider public play their part, by recognising where modern technology has worked wonders?

BRAVO to Burbano, Vanessa, Nicolas Padilla and Stephan Meier!!

Unfortunately modern agriculture has been widely vilified by media for decades often by people who grew up in cities and have never met a farmer in their life. Even drought tolerant crops because they're typically GMOs which are seen as "unnatural" to the media.

One corollary to this is that young women (and young men) may be inaccurately evaluating the social contribution of NGO/nonprofit work. A lot of these organizations are useless or (in the case of climate change activism) even counterproductive.

If you choose the right career path in biochemistry or solid-state physics, on the other hand, you shouldn't have any doubts about the value of what you're doing. And the pay will typically be better as well!