Slave-Raiding, Solidarity and Status in Africa

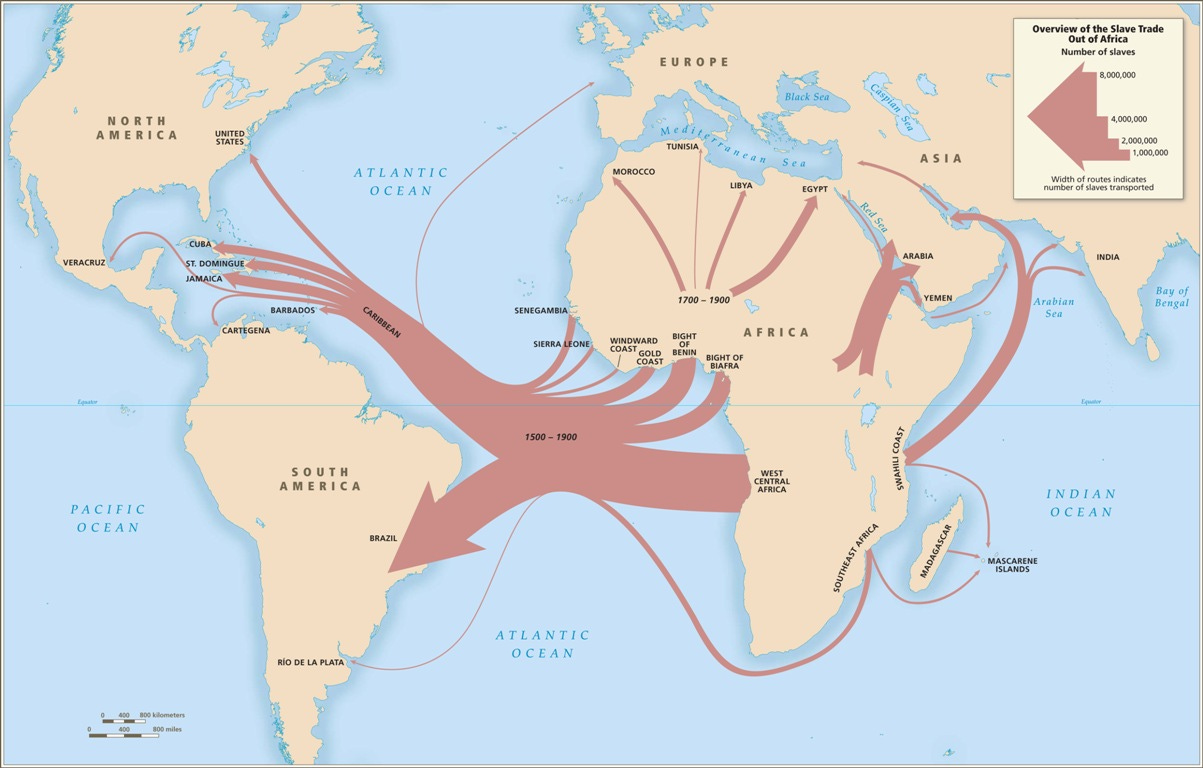

For centuries, millions of African people were captured and coerced into slave trades. The Saharan trade, the Red Sea trade, the Indian Ocean trade and the trans-Atlantic trade all plundered and exported enslaved people. 12 million were taken from Africa to the Americas. A further 6 million people were exported in other trades. As many were coerced into inland slavery - under Islamic states. 300 years of intensive slave-raiding led to predatory states and pervasive insecurity.

How did continuous conflict affect solidarity and status?

Economic historians usually analyse the impact of slave-raiding in the past 500 years, but this can blind us to underlying conditions. If we trace cultural evolution over the very long run, we see that Sub-Saharan Africa’s geography generated strong demand for labour. The slave trades then amplified the returns to slave-raiding, and heightened militarisation.

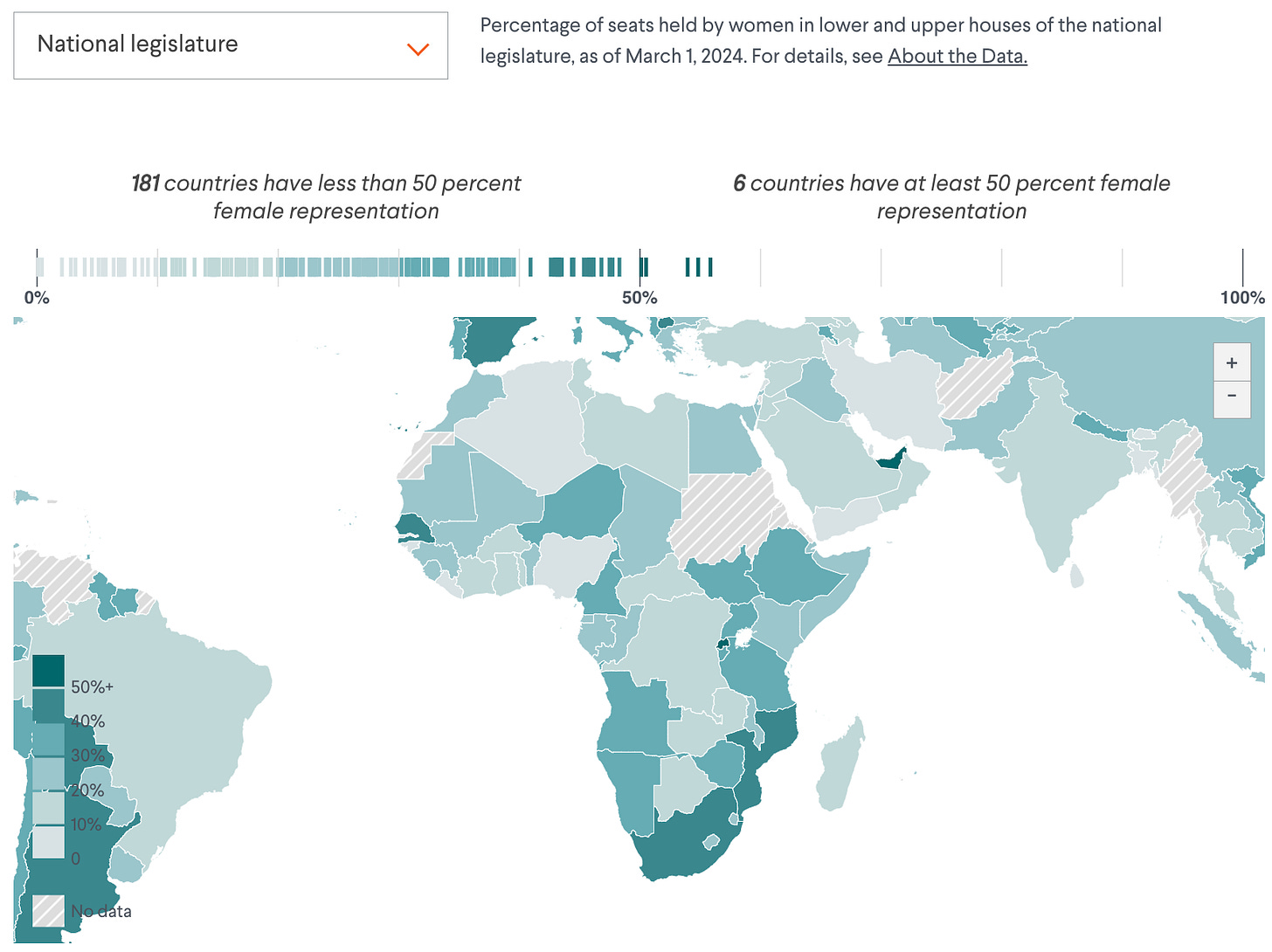

Continuous conflict may have encouraged co-ethnic solidarity and respect for strong men. The trans-Atlantic slave trade disproportionately took young men, while many women were enslaved as concubines and wives in Islamic states. This has resulted in very high rates of polygny, which obstructs gender equality (through high fertility, intimate partner violence, and inter-group conflict). The Gulf of Guinea was most hard hit by the trans-Atlantic slave trade and is overwhelmingly ruled by men.

What encouraged state-formation?

Peter Turchin argues that large empires formed on the steppe frontier, as settled farmers organised to protect themselves from attacks by nomadic pastoralists. Volha Charnysh similarly argues that slave-raiding in Eastern Europe encouraged defensive state-formation. So why didn’t slave-raiding lead to strong states in Africa?

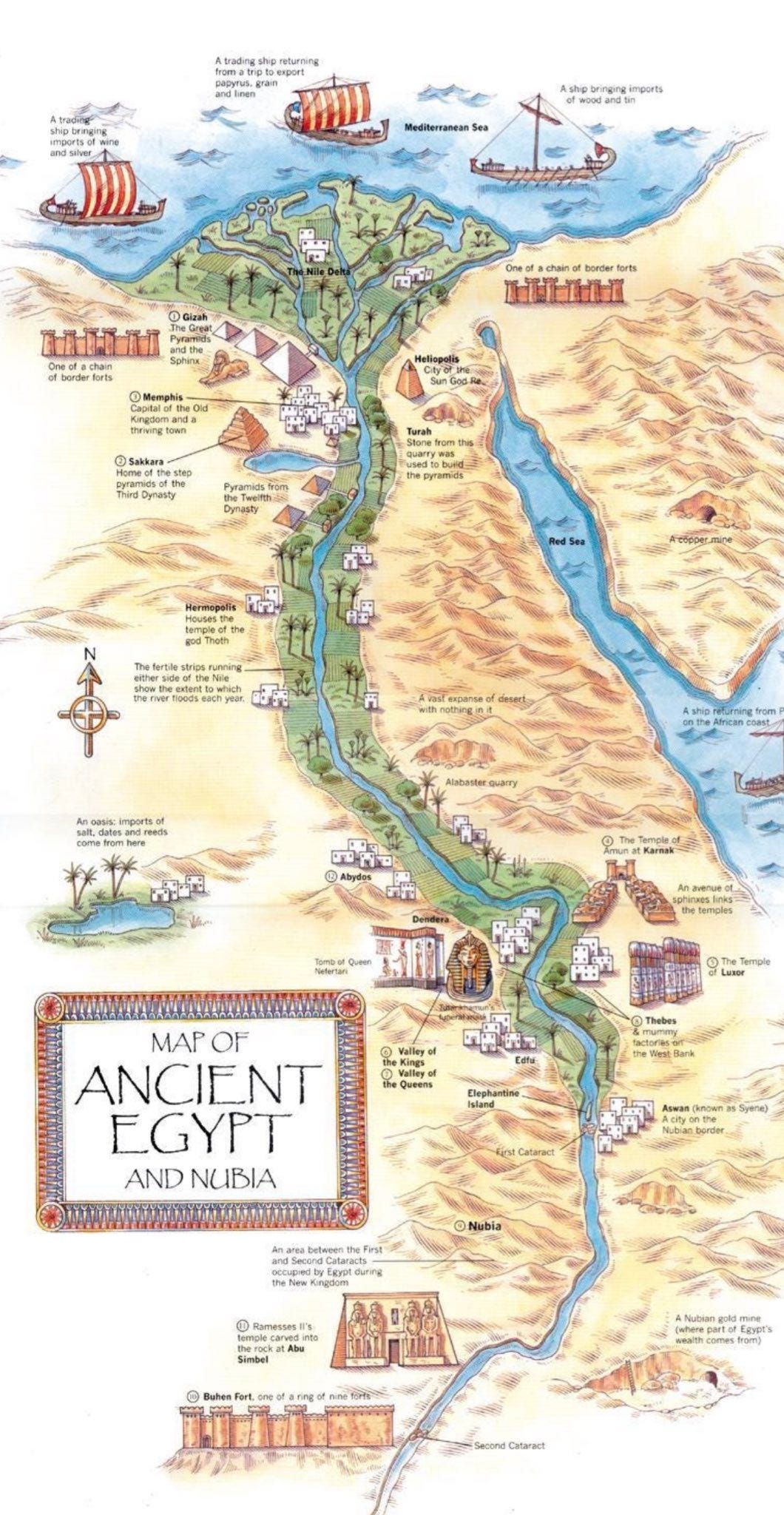

A brilliant new paper by David Schönholzer and Pieter François reveals the importance of ‘circumscription’. They calculate the global heterogeneity in circumscription by computing the difference between the agricultural productivity of one cell compared to all surrounding cells. In the Nile Valley, farming was excellent while exit options were terrible. Circumscription was high. Further south, land was more arid and ‘circumscription’ was low.

Cooperation, conflict and state formation emerged much more quickly and more typically in rich ecologies with weak exit options.

Public goods, defences, irrigation, food storage, currency, and trade were also much more common among pre-state societies located in circumscribed regions.

Ancient Egypt and Ancient Nubia

In mid-4th millennium BCE, Egyptians adopted ploughs and oxen. Owners of these new technologies were increasingly able to command the labour of those without. Dependent on the Nile’s alluvial floodplain, they could not escape. Strong states organised large-scale industries and construction. Egypt’s Great Pyramids were built by armies of corvée labourers, fed by mass-produced bread and beer.

Further south, the Kerma kingdom ruled 2700 BC to 1500 BC. But there is little evidence of complex administration, huge granary storage or territorial fortifications - explains David Wengrow. Writing - a major instrument of state control - came much later. Egyptians developed hieroglyphs in 2700 BC. The Meroitic script emerged two thousand years later and was mostly confined to the royal court. Trade fairs were hosted seasonally at ‘hafirs’ (artificial catchment basins), built alongside temples. Autonomous tribes moved with their herds.

What explains this divergence?

The Middle Nile’s alluvial floodplains were rather sparse. Semi-arid lands favoured pastoralism - suggests David Wengrow. Since Nubian herders moved with their cattle, they were much harder to tax, and this inhibited coercive state development. Weaker state defences also made Nubians much more vulnerable, so they were repeatedly raided for livestock and slaves.

Ancient Egypt was much more circumscribed and saw the early emergence of both cooperation, coercion and state formation. The Kerma kingdom was far less centralised and was continually raided for slaves. This fits Schönholzer and François’s broader finding that states were less likely to emerge in regions where agricultural productivity was more uniform.

Across Sub-Saharan Africa, agricultural productivity was generally low

Revisiting Schönholzer and François’ maps, we see that Sub-Saharan Africa’s agricultural productivity was relatively low. Circumscription was also extremely low. Great kingdoms did emerge, but usually exercised weaker control over their peripheries. Given the abundance of fairly uniform land, people may have preferred to escape and evade centralising control. This likely discouraged state-formation.

African rulers prioritised control over people

Africans have traditionally valued ‘wealth in people’. Labour and capital were scarce, while land was abundant. Low population density made it much harder and more important to control people.

The tsetse fly is pervasive from the Sahara to the Kalahari. It infects and spreads disease in cattle, sheep, goats, camels and horses. The dearth of draft animals likely raised the importance of human labour as substitutes.

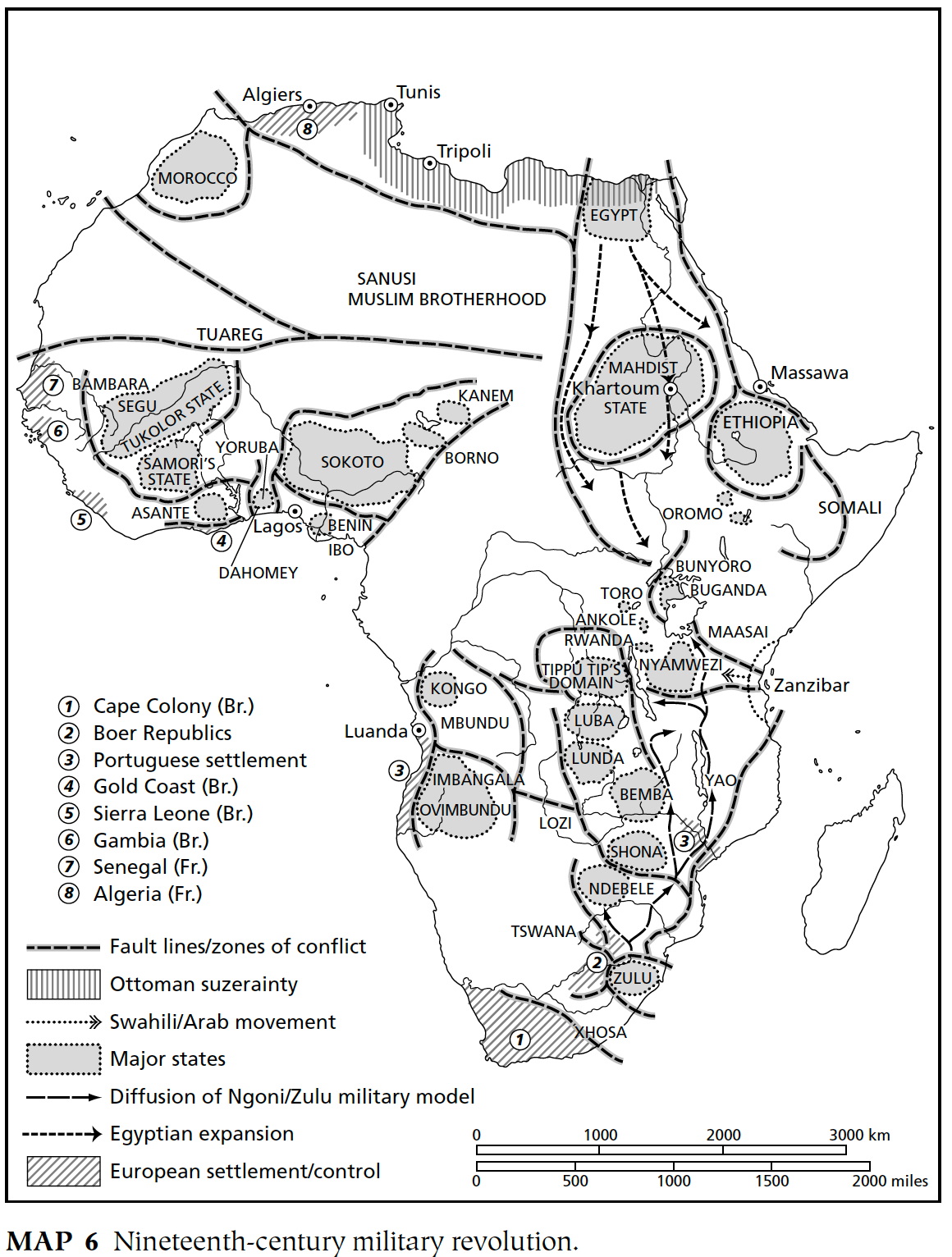

African rulers thus faced a distinctive challenge - argued Jeffrey Herbst. Rather than seeking territorial expansion, they prioritised command over labour. Wars were often waged to raid slaves. 4th century stone inscriptions attest to Axumite kings’ military conquests, seizing slaves and livestock. In the 8th century, the Zaghawa (close to Lake Chad) traded slaves to Muslims further the north in exchange for horses, which they used for more slave-raiding. In the 9th and 10th centuries, the kingdom of Ghana similarly raided slaves, which it sold along with gold to Muslim merchants.

Pre-colonial African rulers’ greatest threat was not international conquest but domestic rebellion. Power was concentrated at the centre, while peripheries were usually delegated to local governors. Historian Richard Reid likens pre-colonial African empires to the spokes of a rimless wheel.

When Arabs and Europeans initially tried to centralise control in Africa (before the 1880s), they failed. State weakness was therefore not a function of culture, but African geography - argues Jason Sharman. In 1590, the Moroccan sultanate failed to conquer the Songhay kingdom. Local Moroccan military leaders became too independent, and developed autonomous slave-raiding ventures. In Southern Africa, the Boers escaped the control of the Dutch East India Company and British Crown, to forge independent republics. In Angola and Mozambique, the Portuguese struggled to maintain local allegiances. Before the 1850s, South Central African ruling families exercised independent control, with their own slave armies (the chikunda).

“Obedience to the Portuguese authorities became a polite fiction, and later even this pretense was dropped, along with Christianity, European dress and family relations, and Portuguese language and literacy” - J.C. Sharman.

Trans-Atlantic demand for slaves enabled African rulers to build more predatory states

From the late 1600s, there was a major external rise in the demand for slaves, to work on American plantations. Sugar, tobacco and cotton were extremely labour-intensive. Deaths in transit, horrific abuse, disease and low reproduction sustained high demand for more victims.

Rising trans-Atlantic demand for slaves gave African rulers opportunities to use external resources to build ‘predatory states’. By purchasing foreign guns, conscripting slave soldiers and using foreign revenue, rulers could pay off subordinates and export more slaves. States became even more extractive.

Sharman suggests that trans-Atlantic demand for slaves enabled African rulers to build predatory states from the ‘outside-in’. Warfare against outsiders was the primary means of generating wealth. Elsewhere in the world, rulers encouraged internal production, which they then taxed to build armies and counter foreign threats. As Tilly famously quipped, ‘war made the state, and the state made war’. State-building was ‘inside-out’.

Why didn’t African rulers tax agriculture? Well, soils generally had low productivity, capital was scarce, and free farmers could easily escape to farm other land. Slave-raiding for export was much more profitable.

Western demand fuelled enslavement on plantations in Africa

As Europe and North America industrialised, so did their demand for palm oil, peanuts and cotton. This created more opportunities for slave plantation agriculture in Africa. Although jihadi movements rose up to overthrow Muslim enslavers, they themselves institutionalised similar economies.

If slave women were taken as wives or concubines, their children had legitimate claims to be free (under Islam). This generated relentless demand for more slaves.

Slavery in the Muslim states of the Sokoto Caliphate, Fuuta Jalon, and Fuuta Toro went on to surpass slavery in the Americas - estimates historian Paul Lovejoy (p. 159).

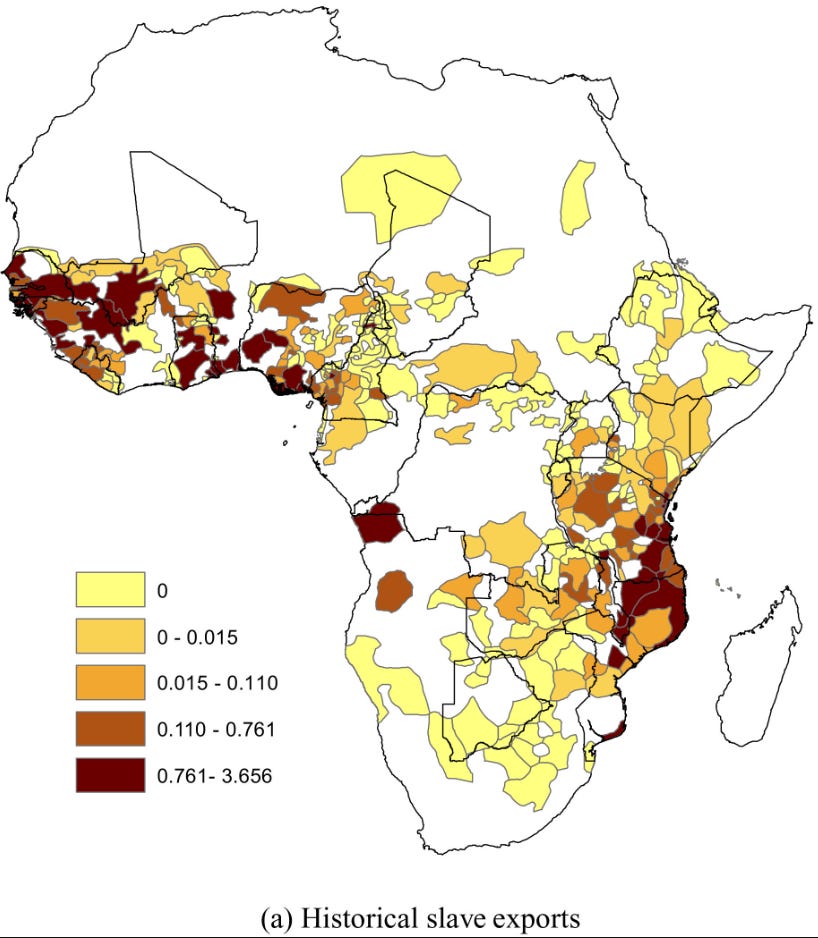

If we want to understand the full impact of slave-raiding in Africa, we must incorporate that caused by the Islamic states in the Gulf of Guinea. So while Nunn and Wantcheckon make an extremely valuable contribution by calculating ‘slave exports’ (using coastline shipping data, as well as foreign markets in Jedda, Sudan and Bombay), West Africa’s total slave-raiding may be under-estimated.

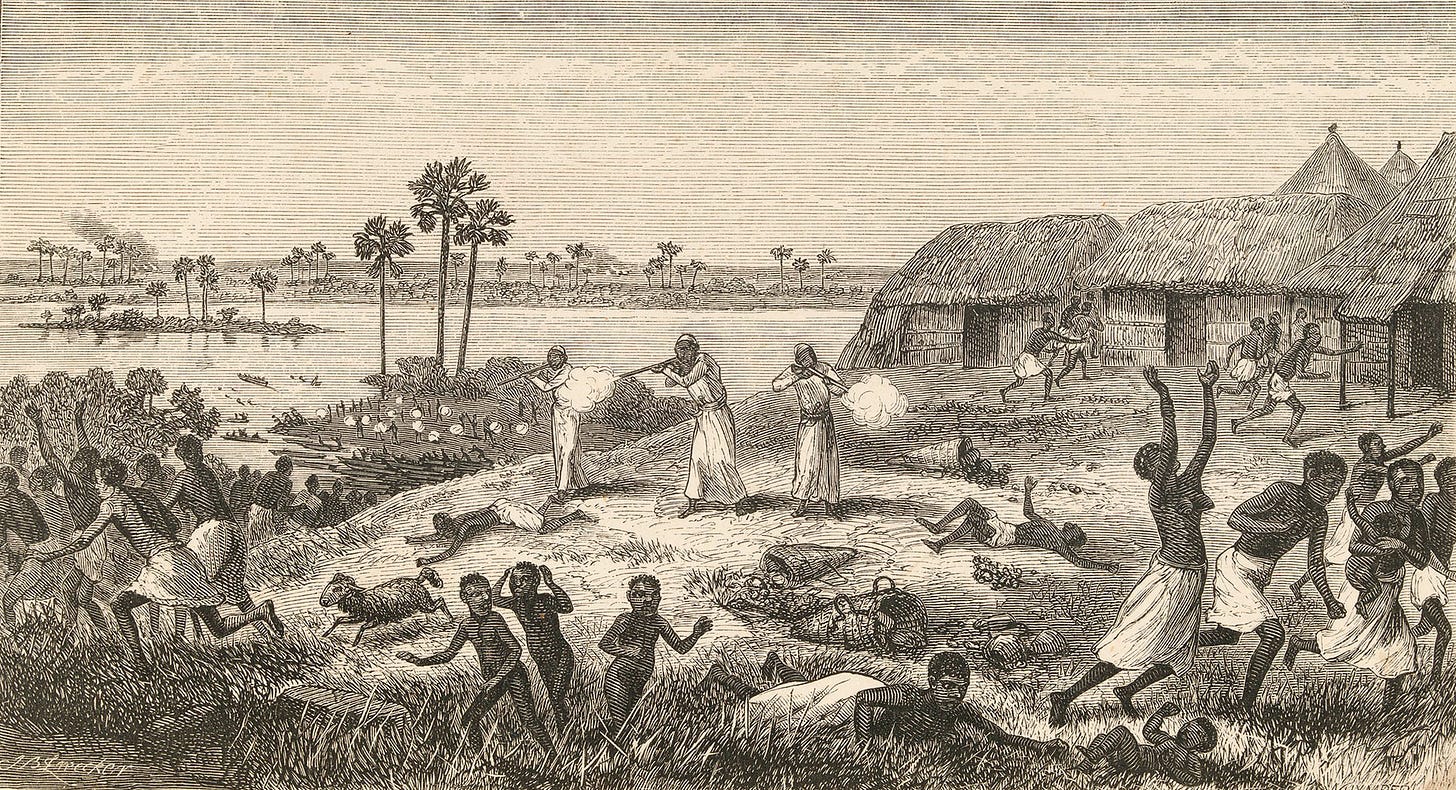

Slave-raiding was incessant; there was endemic insecurity

Predatory military states used slave armies in order to raid and capture more slaves. Warfare was a primary means of generating wealth, especially under adverse climactic shocks. War was ramped up - over hunting grounds - competing to capture more slaves. The primary producer of slaves during the trans-Atlantic slave trade was conflict between ethnic groups. Conquered peoples would either be directly exported, or forced to pay ongoing tribute in slaves.

West African states and societies became especially militarised. Any society that stopped exporting slaves would have less revenue, and become more vulnerable to capture. In the Niger River Valley, young men were conscripted as slave soldiers, while women were forced to farm. According to a French observer in the 1880s there was,

“incessant warfare.. to capture women, children and young men in order to sell them”.

In Souroudou (Burkina Faso), another French observer reported,

“There is a shocking anarchy reigning in Samo country: the pathways are not safe; one ventures out with one's bow and arrows and returns with booty, the product of banditry. Unfortunately, the Dioula, particularly those coming from Bandia-gara, encourage this unstable situation by buying captives. For one cow or one bar of salt, a Dioula can purchase a slave, who was probably captured the day before in a neighboring village”.

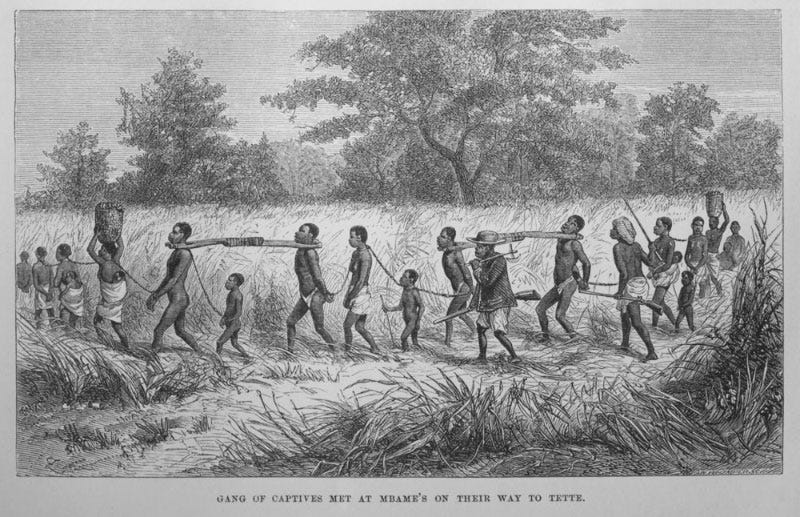

By 1840, 40% of the population of Zanzibar were slaves - usually captured by Arabs for the Sultanate. Constant predation spawned endemic insecurity. Terrified people sometimes escaped to hide in the tropical forests, abandoning their crops.

Equatorial Africa suffered from incessant slave-raiding - especially from Darfur. Manhunting (chasse à l’homme) continued under French colonialism. The French wanted porters to carry their heavy loads, but Africans resisted, so the French relied on labour coercion. The French also recruited non-local guards, who they did not properly feed. These guards plundered villages en route - to expropriate food and rape local women, tying them together at the neck.

“He gets himself carried by tipoye, demands five or six chickens for his daily food, and beats the natives when they do anything that does not fully please or satisfy him” - observed a colonial officer, who typically turned a blind eye (quoted by Lombard 2020).

Father Joseph Daigre (a missionary in Banda country) observed,

“Auxiliaries [militiamen] behave like police and hunt out all the gatherers who try to escape the ordeal. It is common to meet long lines of prisoners, naked and in a pitiful state, being dragged along by a rope round their necks. Countless poor wretches are taken along the remoter tracks, completely stupefied by the harsh treatment. They are famished, sick, and fall down like flies… The really ill and the little children are left in the villages to die of starvation. Several times I found regions where the people least affected killed the ones who were dying, for food” (quoted by Lombard 2020).

Terrified people fled their villages - explains Louisa Lombard. In 1896, Émile Gentil remarked upon Mansa’s immense millet and manioc plantations. Four years later, adventurist Fernand Foureau only saw rot. A colonial officer complained,

‘We track them in the bush where they prefer to seek refuge and die of hunger rather than carry our loads’.

How did slave-raiding impact culture?

300 years of slave-raiding likely affected culture. The question is in how?

Intensive raiding and insecurity have long-run cultural effects - as demonstrated by Nathan Nunn and Leonardo Wantchekon. Africans who distrusted others may have been more likely to evade capture and then socialise their children to be distrustful. Today, distrust of relatives, neighbours and local government remains higher in places that suffered intensive raiding.

Meanwhile, Whatley and Gillezeau find that slave exports are strongly correlated with more ethnic groupings today. The Gulf of Guinea suffered most severely from the trans-Atlantic slave trade (due to its physical proximity to the Americas) and now has acute ethnic divisions, stratification and distrust.

Colonial borders may have compounded these effects: grouping multiple ethnicities into large states. Alesina and colleagues introduce the term ‘artificial states’ for places where ‘political borders do not coincide with a division of nationalities desired by the people on the ground’. I would add, it’s not just about the imposition of political borders, but also weak states and the the dearth of public goods, which are fundamental for nation-building.

Existing studies suggest that slave-raiding amplified distrust and differences, while strengthening ethnicity. How can we make sense of these findings?

Slave-raiding likely encouraged ethnic fraternity

Groups may have been more likely to evade capture if they had strong fraternal solidarity. Weapons alone were no safeguard, since any one man could have prospered by turning on his neighbours and selling them as slaves. After that, the group would become smaller and unable to mobilise defence.

Large groups are key, but these could only have been maintained if every man downplayed his individual advantage and prioritised the group. I suggest that men united in loyalty would have been more likely to survive as a cohesive group.

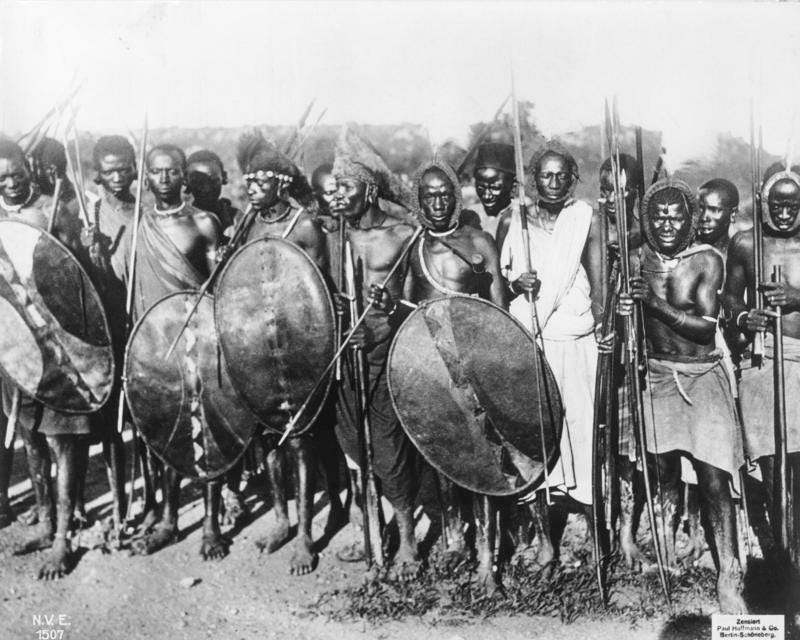

Fraternal solidarity is fundamental - due to men’s biological advantage in warfare. Testosterone is 5-20 times higher in males, especially young males. Testosterone promotes muscle development during puberty. This is why males generally have greater body strength and pack a more powerful punch. Testosterone is also associated with violent aggression. But it is not static: it surges with competition and success. The fighting forces - which protected the entire group - were almost always men. Group survival thus depended on brotherhood.

Ethnic groups waged war to amass wealth, gain honour and protect their people. Dahomey, Asante and Yoruba city-states competed against each other. Historian Richard Reid details that ‘faith and identity both drove these wars and were called into service to justify them’. So while others have emphasised distrust and divisions, I suggest we recognise the power of ethnic brotherhood. Groups with stronger bonds may have been more likely to survive, because they sacrificed self-interest to maintain group strength.

Dahomey was an exception. Its army of 12,000-15,000 included female soldiers; 5,000 were under female commanders. But that was unusual; other armies were overwhelmingly male. None of this negates women’s important contributions as mothers, nor does it deny the importance of wider social cohesion. My only point is that in times of inter-ethnic war, groups really benefit from fraternal solidarity.

Cultural traits that were advantageous during the centuries of violent slave-raiding may persist today - if surviving parents encouraged their sons to look after their own, band together as brothers, and build supportive networks. Peers can also strengthen club-like solidarity by punishing those who show excessive loyalty to outsiders. This is not inconsistent with Nunn and Wantcheckon. Ethnicity is a selective form of solidarity, within a wider context of distrust.

Slave-raiding may have raised co-ethnic men’s status

In her brilliant book on “Status”, Cecilia Ridgeway theorises that groups gain status when they are seen as making valuable contributions to the group. At football matches, fans cheer for super-star players who score the most points. And when the Kaiser City Chiefs won the Super Bowl, fans mobbed to celebrate their heroes. Likewise in law firms, praise is lavished on partners who secure lucrative clients. Alexei Stakhanov was a Soviet miner, heralded as a ‘Hero of Socialist Labour’ - because he supposedly mined 227 tonnes of coal in a single shift.

If a group has high status, this means that they are treated with respect and deference, their words carry more weight, and they are seen as leaders. Low status groups, meanwhile, are expected to serve and be subservient.

In certain times and places, African women did exercise spiritual power and moral authority. Learning from oral histories, Nwando Achebe reveals women’s importance as goddesses, priestesses, oracles, deities, and queen mothers. Cosmology upheld gender complementarity. The Asante, Igbo and Yoruba also had dual sex systems of governance. Women had independent networks and separate spheres of influence. Markets in the Gulf of Guinea were controlled by women - who set the rules and punished wrongdoers.

But I suggest that during endemic slave raiding, co-ethnic men may have gained status. Like almost all wars, African wars were primarily waged by men. Military strategy and warfare were overwhelmingly orchestrated by men. Victory brought honour and celebrations. Richard Reid suggests that military prowess was the surest way for a young man to gain status. Women ululated and cheered for their saviours. Military honour and courage were celebrated in the Benin Bronzes, the Epic of Sunjata, and Ganda culture. Whether societies were organised by kinship or age-mates (like the Maasai), group competition motivated militarisation.

By saving their communities from capture, co-ethnic men may have become revered as vital protectors. Intersectionality is really critical. I am specifically stressing ‘co-ethnic men’. We should not expect inter-ethnic slave-raiding to cause generalised fraternity, or reverence of all men. Non-ethnic men may be viewed as dangerous threats.

Attitudinal surveys usually examine gender bias, rather than intersectionality. So, it’s hard to test my hypothesis that slave-raiding increased co-ethnic men’s status. But support for male leaders does seem especially strong in Nigeria (which was especially hard hit by slave-raids). This holds for both Muslims and Christians.

Ethno-religious fragmentation may have weakened women’s movements

In Eastern and Southern Africa, civil wars and especially post-conflict nation-building have provided opportunities for women’s movements to press for gender quotas. Eager for donor funding, authoritarians have often used quotas to strengthen international legitimacy.

But campaigns for gender quotas have been far weaker in West Africa. I suggest that they have been hampered by ethno-religious fragmentation. Women who primarily identify with their ethnicity may have little appetite for such campaigns, since she is loyal to her ethnicity. An Igbo woman may prefer to be led by an Igbo man than a Hausa woman. Even if women privately support gender quotas, distrust may dampen willingness to invest in sustained mobilisation across ethnicity. Activism becomes sporadic.

Polygyny

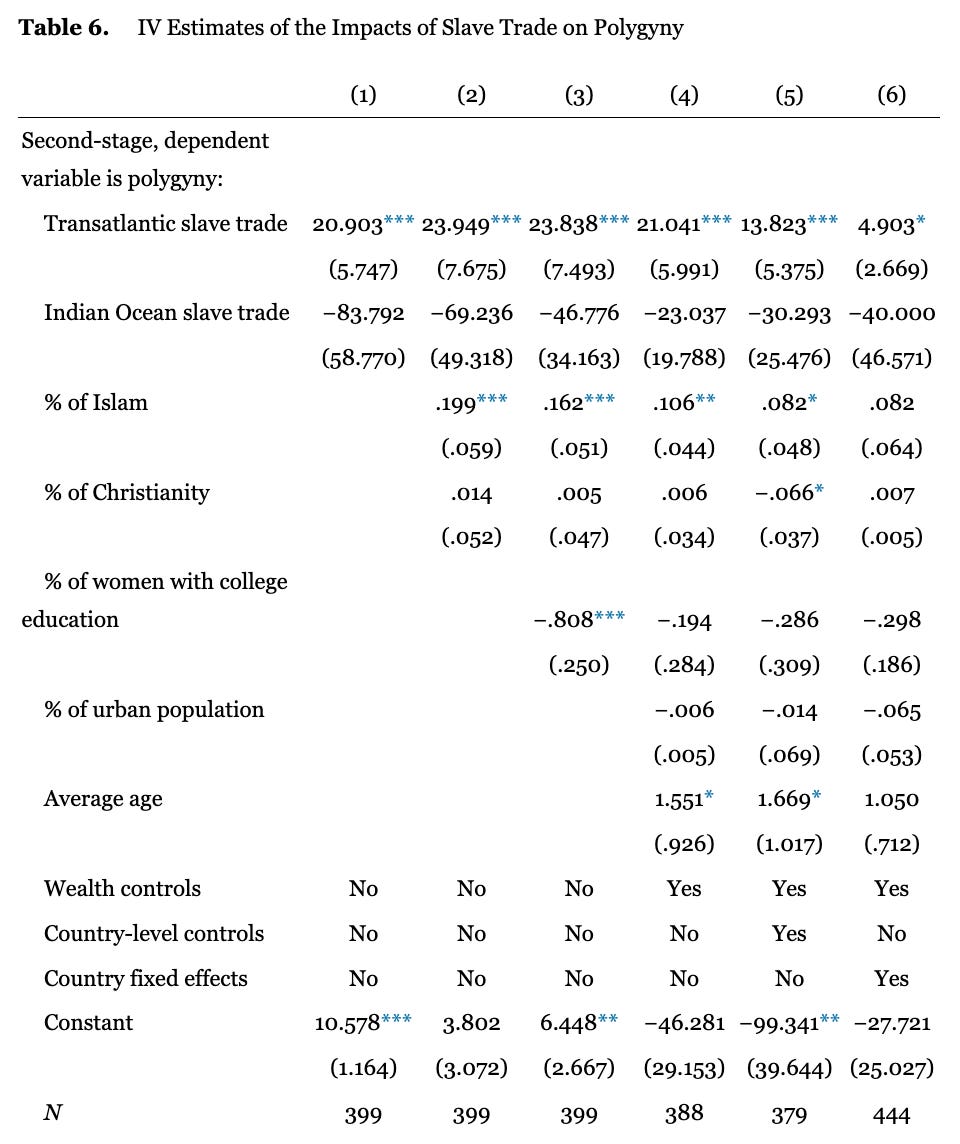

Polygny is pervasive across Muslim areas of West Africa. Economists Dalton and Leun suggest this is because the trans-Atlantic trade disproportionately exported enslaved men, created long periods with uneven sex ratios. Women may have then become polygamous co-wives.

Analysing Demographic and Health Surveys, they find that ‘Muslims tend to have more wives than people of other religions like Christians’, and suggest this is because ‘Islam allows up to four wives, while Christianity forbids polygyny’.

Polygny may have been initially encouraged by the trans-Atlantic slave trade, but it was subsequently idealised by the jihad slave states. The Sokoto Caliphate seized enslaved women to become wives and concubines. Enslaved women were valued for both farming and fertility. Polygny gained prestige - emulating the Prophet and marking men’s military might. (Enslaved men were not permitted wives). So polygny isn’t just permitted by Islam, it also signifies status. This help explain its cultural persistence among Muslims.

Polygny creates cultural barriers to gender equality

Women in polygynous countries marry 5.1 years earlier and have 2.2 more children than those in monogamous countries - finds Michele Tertilt. By marrying early and bearing more children, women are then economically disadvantaged.

Polygamous unions can be fraught with conflict and competition - as I was frequently told during nine months of research in the Gambia. Bright Opoku Ahinkorah’s analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys suggests that polygyny is a major predictor of intimate partner violence.

Yet despite these risks, women may feel unable to refuse. In the Gambia, Isatou worked extremely long hours for many years as a nurse, built a large house, only to discover that her husband had taken a younger wife. She was absolutely distraught, but felt totally powerless. In Burkina Faso, husbands may also threaten their wives with (unwanted) polygny in order to enforce obedience.

Polygny, bride price, and disadvantaged young men

Bride prices are usually paid in African countries that are polygamous. By selling their daughters, fathers can procure additional wives. Poor young men are thus competing with older, established men. This generates inflationary pressures on bride prices. Moreover, Gambian women usually seek men who can provide financially. Poor young men then feel immense struggle and sadness - as they shared with me:

Francis (a 34-year old woodcarver) lost a girlfriend to an arranged marriage because he was “...not yet strong enough and they would not wait.”

Solomon (27 years old) wanted to marry his girlfriend but he was “not that much strong and not ready to handle myself, or someone else... Even myself... to take care of myself is a problem.”

“If you are chasing a girl, before she accept, she will like to know whether you are [financially] strong or not... They don’t care for boys unless you get. That is the main problem here in The Gambia between the boys and the girls” (Mohammed, 24 year old chef, electrician and plumber)

“They will underrate because you’ve got nothing to give” (Abdoulie, a 30-year old woodcarver who shares a bed with a male friend, as he couldn’t afford his own bed).

In polygamous societies, grooms must acquire enough resources in order to marry or find much younger women. This results in large spousal age gaps. Michele Tertilt finds that in polygamous societies, brides are usually 6.4 (rather than 2.8) years younger than their husbands.

In Burkina Faso, a man marries a wife (not the other way around). A good wife then ‘endures’ (muɲu, in Manding). By paying the bride price, the husband gains ownership of the children. Indeed, West Africans tend to say that children belong to the father. They are not her lineage.

Across Africa, women farmers are often less productive. This is because they are less able to command labour. In Niger and Northern Nigeria, women are disadvantaged both in terms of land and labour - because their children are not their own.

Polygamy is especially high in Northern Nigeria. Poor young men struggle to compete with established older men and afford high bride prices. This may be contributing to violent conflict - such as the Salafist-jihadist group Boko Haram, which has killed over 35,000 people and in March 2024 abducted hundreds of women and girls. To recruit poor young men, Boko Haram offer inexpensive weddings.

Conclusion

Sub-Saharan Africa suffers from low agricultural productivity. Land was undifferentiated and abundant, the tsetse fly killed cattle, while labour was scarce. Prosperity depended on wealth in people. Foreign and internal slave trades amplified demand, resulting in centuries of slave-raiding and militarisation.

Polygny appears to have been encouraged by the trans-Atlantic slave-trade and jihad states. This inhibits gender equality (through early marriage, high fertility, lineage, intimate partner violence, and inter-group conflict). Women are quadruply disadvantaged.

The trans-Atlantic slave trade and relentless slave-raiding may have bolstered co-ethnic solidarity and male status. This could explain why cabinets are male-dominated in African countries where ethnicity is heavily politicised.

The Gulf of Guinea was hard hit by slave-raiding and is overwhelmingly ruled by men. Ghana’s parliament is 85% male, the Central African Republic’s parliament is 89% male, Nigeria’s parliament is 96% male.

In some respects, Africa is not unusual. Terrified civilians usually want big strong patriarchs. When people are under attack, they typically seek macho leaders. Geo-political conflicts and terrorist attacks generally erode public support for women. Cross-country regressions and natural experiments confirm this broader trend. Peace and security are hugely important pathways for gender equality - in Africa and worldwide.

Previous Essays

Further Reading

“Female Monarchs and Merchant Queens in Africa” by Nwando Achebe

“Africa: The Historical Roots of Its Under-Development” by Emmanuel Akyeampong, Robert Bates, Nathan Nunn, and James Robinson

“The Legacy of Arab-Islam in Africa” by John Alembillah Azumah

“Resources, Techniques and Strategies South of the Sahara: Revising the Factor Endowments Perspective on African Economic Development, 1500–2000” by Gareth Austin

“Looking for the one(s): young love and urban poverty in The Gambia” by Sylvia Chant and Alice Evans

“The puzzle of monogamous marriage” by Joseph Henrich, Robert Boyd

and Peter J. Richerson

“States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control by Jeffrey Herbst

“In Plain Sight: The Neglected Linkage between Brideprice and Violent Conflict” by Valerie Hudson and Hilary Matfess

“Hunting Game: Raiding Politics in the Central African Republic” by Louisa Lombard

“Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa” by Paul Lovejoy

“Jihad in West Africa during the Age of Revolutions” by Paul Lovejoy

“Women and the War on Boko Haram: Wives, Weapons, Witnesses” by Hilary Matfess

“Tribe or Nation? Nation Building and Public Goods in Kenya versus Tanzania”

Edward Miguel

“Power and Landscape in Atlantic West Africa: Archaeological Perspectives” edited by J. Cameron Monroe and Akinwumi Ogundiran

“The Slave Trade and the Origins of Mistrust in Africa” by Nathan Nunn and Leonard Wantchekon

“Polygyny and intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from 16 cross-sectional demographic and health surveys” by Bright Opoku Ahinkorah

‘“Unwilling Cocoons”: Boko Haram's War Against Women’ by Temitope B. Oriola

“Warfare in African History” by Richard Reid

“Status: Why Is It Everywhere? Why Does It Matter?: Why Is It Everywhere? Why Does It Matter?” by Cecilia Ridgeway

“Something New out of Africa: States Made Slaves, Slaves Made States”

J.C. Sharman

“Environmental Circumscription and the Origins of the State” by David Schonholzer and Pieter Francois.

“Polygyny, Fertility, and Savings” by Michèle Tertilt

“Women in Ghana at 50: Still Struggling To Achieve Full Citizenship?” by Dzodzi Tsikata

“Nation Building: Why Some Countries Come Together While Others Fall Apart” by Andreas Wimmer

Rocking Our Priors

“Why does Rwanda have a strong state while CAR is war-torn?”. podcast with Professor Louisa Lombard (author of the Hunting Game, and State of Rebellion)

“Female Monarchs and Merchant Queens in Africa”, podcast with Professor Nwando Achebe.

Pre-Ordering

“How to Become a Big Man in Africa: Subalternity, Elites, and Ethnic Politics in Contemporary Nigeria” by Wale Adebanwi (out in August)

Africa is now majority Protestant Christian. How does it impact clan dynamics since Catholic Christianity destroyed clans in Europe? Do you see a growing reduction in kinship intensity in very religious Christian communities in Africa?

So strong a set of arguments for rejecting other worldviews and embracing (which includes acting on, or implementing) the Judeo-Christian, or biblical worldview. Not necessarily Western interpretations--remember, the Hebrews including Jesus were/are Asian--but applying principles of love and right living based on solid fact, and illuminated in the Bible.