"Female Monarchs and Merchant Queens in Africa": Professor Nwando Achebe

Alice: Welcome to Rocking our Priors, I am delighted to welcome Professor Nwando Achebe, Professor of History and Associate Dean at Michigan State University. Today, we are discussing her monumental new book, "Female Monarchs and Merchant Queens in Africa". If you would rather listen than read, this podcast is on iTunes and Spotify.

Alice: Professor Achebe, welcome!

Nwando: Thank you so very much, Dr. Evans. It's just such a pleasure.

Alice: Suppose you and I traveled back in time before the transatlantic slave trade before colonialism, do you think we'd find greater gender equality in Europe or Africa?

Nwando: Definitely in Africa, definitely in Africa. What we see today in Africa has everything to do with our colonial past. And so African women are trying to get back to a semblance of their precolonial past.

So in the pre-colonial era for the most part, I would say that you had systems in Africa that work complimentary. I also use the term "dual sex systems in operation": each sex in Africa took care of what was important to them. So you had men taking care of what was important to men and women taking care of what is important to women. And it didn't matter whether you were talking about a centralized system or small-scale societies that have no Kings or Queens.

Methodology

Alice: How can we know what gender relations were like back then?

Nwando: I'm an oral historian by training. Language is culture. It is the way of seeing and being in the world. So without an understanding of one's language, you cannot understand the world that we live in. And that's my starting point. You cannot be an oral historian without language, right?

The archives obviously are what we are most familiar with, but people tend to think that those archives just emerged and they're not biased. [But] the archive came to be as a result of the colonizing enterprise. And you can't expect your colonizers (who are there to take away your land) to write glowing stories about you. But that doesn't mean that I do not look at the archives, right? So I look for history and evidence in proverbs, proverbs that explained society to itself, in song. When I do women's history, I look at jewellery history. I look at cloth history. I necessarily have to go in search of history, wherever I can find it because these colonial masters that put together that which we now have as history right in the archive did not, for the most part, concern themselves with women's realities. It was white men going into the African rural areas and interviewing old black men about whatever, right? And very seldom did we get the point of view of African women. And so, yes, it's in there, but you kind of have to search for it.

Alice: Can you give me some examples?

Nwando: Let me give you an example of the gender neutrality of African languages. So English for me is a learned language. So I'd like to go back to my mother tongue: Igbo (the new population numbers are about 40 million right now). There is no term for brother and sister. It is the same term. So brother is nwanne. Sister is nwanne. 'Nwanne' means the child of my mother. And this is why if Africans are speaking in the English language sometimes they mix up gender, right? If they want to say he, they say she. It's because in our indigenous languages, that's just non-existent. So that's one good example of the gender neutrality.

God as the creator of everything is neither male or female in most African societies. God is the male and female forces coming together. But because we are stuck with these gender specific languages - European languages, English, French, Portuguese, German - African writers that are writing in these European languages have necessarily had to write in ways because the English language doesn't allow you to really sort of describe a gender neutral force. So I even talked to my students about people of my dad's generation, right (Chinua Achebe, author of "Things Fall Apart"). He talks about God. God is not he, but that was all that the English language allowed him to do.

Alice: I speak Bemba, which is a Bantu language in Zambia and the DRC. The name for women is banamayo and that really means mothers of mothers, while men are bashitata (fathers of fathers). I think that speaks to your point about "dual sex governance". Also in, in Bemba, a woman is called by the name of her first child, regardless of whether its male or female. And I think that resonates with the importance of fertility and how women gain respect by giving birth.

Nwando: Fertility is so important that you don't necessarily as an African woman have to physically right give birth to become a mother. So I talk about biological parenthood in Africa being subordinated to social parents. Fertility does not necessarily in the African context have to be biological fertility, it could be socially.

Alice: That reminds me, on methodology, if you look at sculptures from Southern Nigeria or Benin, it's always that "gender complimentarity", it's the man and the woman. Some emphasize fertility, with particular body parts.

Gender fluidity and female husbands

Nwando: I was going to talk about gender fluidity: fluid, and flexible. You can be born female, right. But be categorized as socially male and there's no tension. Gender is fluid and flexible and allows biological females to become male. I have an article talking about the female king of colonial Nigeria where I say, "and she became a man". And I have another article talking about male priestesses. So there is no tension, no conflict.

It's because of this flexibility and fluidity that you have the institution of female husband, where a woman can marry. And again, it's about this fertility that we're talking about, right? A woman can marry another woman. And if I am doing the marrying, if I decide, I want to marry you, Alice, what am I going to do?

Alice: Pay the bridewealth.

Nwando: Exactly. I am assuming the positionality of husband. And so I become what is called the "female husband". Female is my sex. Biological sex husband is my gender. And I want to marry you. So I have to pay bride-price, bride-wealth, or even bride-service [performing labour for the bride's kin], which has absolutely nothing to do with you, but it has everything to do with the children that you will be giving to me. Non-biological but still I become a parent because of this.

Alice: Forgive me for not understanding, but doesn't that schema imply a degree of gender hierarchy? If it's the husband who has the rights to the children, if it's the "husband", with masculine characteristics, who has all those rights and entitlements doesn't that imply a gender hierarchy? If there was total gender equality, surely we wouldn't call that authoritative rights-bearing position "husband"; we'd just just say anyone could have it.

Nwando: Let me trouble that a little bit. I like to start by saying, and it goes back to fertility and the importance of children in Africa. Every single child belongs. Right? So this whole idea of an illegitimate child came out of Christianity, it came out of the colonial enterprise. Pre-colonially African women did not take their husband's names because African women are long-term visitors in their husbands homes.

So that whole idea of bride-price, bride-wealth, bride-service has absolutely nothing to do with a woman. It has everything to do with the children.

Why is that important? If bride-price/ bride-wealth, bride-service is not paid, those children belong to the mother: bear her name and belong to her lineage. So a child always belongs. And so when you talk about the husband, he has rights over those children because he is in fact paying for those rights.

Bride-price, bride-wealth, bride-service has absolutely nothing to do with the wife. It has everything to do with granting the husband rights over his future children. It's a transfer of rights by payment.

A more apt term for it in English should be "childcare rights" and "child service" because it has everything to do with granting this man and his lineage rights over the children. And those rights begin with the right of that child to bear his name; without that kids don't bear their names.

Alice: Relatedly, in Africa, people traditionally valued "wealth in people". People accumulated wealth by having children. So, so control over labor was imperative. It wasn't about how much land you had; land wasn't high value. What you really wanted was "wealth in people".

Gender in African traditional religions

Alice: In Eurasian religions - in Hinduism Islam, Judaism, Christianity, Confucianism, Daoism - women were not really revered as knowledgeable authorities. Can you tell me more about women's role in traditional African religions?

Nwando: In my first book, I argue that you cannot understand African history by focusing exclusively on the human visible world. That is to tell just one part of history that is a fundamental misunderstanding of Africa.

The African world, the way that Africans conceptualizing world, is in duality, right? The physical human world, the seen world, I'm looking at you. You're looking at me. We are seeing each other is actually a less powerful world than the unseen world. So we believe that there are spirits all around us. We just can't see. And so what I've tried to do in my work is to historicize those spirits.

So in the African world view, I move away from "women", I call it "the female principle". I use that term, "a female principle" to talk about religion because for the most part, we're not talking about human women, even though human women were extremely active. And in African religiosity, there were priestesses, there were prophetesses. But even more powerful was what I call "the female spiritual principle". God, the Supreme God creator of everything, was neither male or female, but a combination of both and God was too big to be worshiped direct, right? And so Africans sort of relied on these gods and goddesses that are called lesser gods and goddesses who were person personifications of natural phenomenon.

In the African context, the most important, the most powerful of these lesser deities were in fact female.

And how do I arrive at that? In order for people to survive, you need water, right? Without water, you are dead. The other thing that you need is food and you get your food from land. So those two: water and land. What are the deities in the African system that are in charge of water and land? For the most part, they're female, the goddess of the waters and the goddess of the land.

There are over 3000 different African nations of people, that speak different languages and have different cultures. So we have to generalize sometimes when we talk about Africa, because it's such a vast continent. I am saying that for the most part, deities in charge of land and water are the most important and most powerful of deities.

That's especially true when we figure into the equation that God, for the most part is not worshiped directly worshiped by Africans, right? God is paid high respect. We worship - in the traditional system - the deities, the lesser gods and goddesses. So they are so much more present in our lives. And like I said, the most powerful are female. And as you go down it's, you will see this "complimentarity" that we're talking about. God is both right?

When you have a female deity, for the most part, you have a male priest in charge of the female deity. When you have a male god you have a female priests, this complimentarity.

Maleness and femaleness make this complete entity, which is this balance balancing male and femaleness is what African cultures is looking for.

Female networks of solidarity

Alice: Can you tell me more about female networks of solidarity? E.g. Igbo women meeting together, discussing their issues and then "sitting on a man", protecting that turf from male encroachment.

Nwando: In small-scale societies, such as the society of my birth [Igboland], leadership is in the hands of a group of male elders and female elders. Age is so important in these cultures. That's what sets you apart from people who are younger, right? In these small-scale societies, you don't have one king or queen. In fact, they have proverbs that tell you, "if you want to be a king, go be a king in your mother's backyard". That's an Igbo proverb. We don't like kings. And we have another one that says when, "The Igbo have no kings", they don't respect kings. It's leadership in the society and in the group.

So in societies like that groups of women come together, right in order to lead themselves, in order to support themselves. So instead of having one person in charge, you have groups of women in charge, women coming together to go to the marketplace, women coming together, forming groups to work on this person's farm, because I need help. And then tomorrow I will work on somebody else's farm. Right? So groups of women helping each other out, right. Also forming credit systems. Women would come together and every month put in a certain amount of money into this pool. If you Alice needed money "I want to do a little expansion to my home", you would just come to our group and we as women will loan money to one another without interest.

You see women using nudity to protest. "Sitting on a man" is really the most extreme form of punishment that women have. You see it in East Africa, you see it in South Africa, women using nudity to say "enough is enough". It's a punishment waged on men, right? If you continue, we will act and we'll act in a manner that you're not going to like, right.

Alice: I read an interesting conceptualization of the nudity protests. In Ukraine, FEMEN women are naked as a form of maintaining ownership of their body and challenging the cult of chastity. But Kathleen Sheldon conceptualises African women's nudity protests as reminding men that they came from a woman. So it's to remind men of women's importance our fertility. I wonder what you think of that?

Nwando: You have it, that is it a hundred percent. It is to remind the community that a mother's body is powerful. Motherhood is so vitally important and powerful. It is the mother that creates the ruler. It is the mother that creates a society. Without the mother's womb, society does not exist. The mother gives birth, she creates and continues the world.

Alice: Yes, and as you highlight in your book, the Queen Mother is the king pin. She has huge authority. She might even have her own court.

Which African societies were more gender equal?

Nwando: It is a difficult question because you're talking about a huge continent, but it seems as though the less centralized a society is you start to see a lot more of this equality, flexibility, and complimentarity. And it's not to say that you don't see it in centralized societies because the Asante have the Queen Mother, who decides on who the king is going to be. But in East Africa where societies were so centralized a woman's position in society really had everything to do with her rank. And if she was not blessed to have been born from one of these like a queen mother or princess then perhaps her status in society is not that high.

But even in those [centralized] societies, there were always mechanisms for women to elevate themselves. Women could become spirit mediums and rise to the level of these male kings and the queen mothers, the Buganda queen mothers and princesses.

Alice: Let me give you two concrete examples. I think women were only 10% of the anti-colonial protesters in Kenya - a relatively small proportion as compared to the Aba women's protests in Nigeria. Also, in West Africa, women controlled the markets. That seemed to be a distinctly West African phenomenon, unless you correct me?

Nwando: That's a million dollar question. I personally don't know why are women owning the markets mainly in West Africa. Another question could be, why are there spirit mediums in East Africa, in the Horn of Africa, in Southern Africa, but not in West Africa? We don't have spirit mediums, but we have spirit possession.

Alice: What's the difference between spirit medium and spirit possession?

Nwando: In Southern Africa, East Africa, the Horn of Africa, North Africa, there are groups of people who have been possessed by a spirit, collectively challenging established rulers. We don't see that in West Africa. I don't know why.

Female circumcision

Alice: I have another conundrum. The Gulf of Guinea seemed simultaneously oppressive and respectful in some ways. Women organized to protect their turf against male encroachment They moved freely in the public sphere. They gained independent wealth and authority. When the Portuguese came to the coast of West Africa, they had to deal with women. Women often married Portuguese traders. They had their own independent wealth, trade and networks. You can correct me on what word we use here, but there were also some very oppressive practices.

Let me give two examples. One, pawnship, the domestic institution of slavery, whereby most of those enslaved people were women. Women were enslaved by their fathers or uncles, they covered debts. And so doesn't the fact that it was mostly women who were enslaved indicate their low status within the household, that they could be so vulnerable?

Secondly, the Yoruba clearly revered female authorities. But if we look at female genital mutilation today, 50% of Yoruba, 50% of Igbo women have been genitally mutilated. And that's usually explained in terms of marriage ability, girls are cut to please men and enhance their marriage prospects. And so how do you make sense of those apparent contradictions?

[Edit: I subsequently checked Demographic and Health Surveys. In 2003, prevalence among Yoruba and Igbo was estimated as 61% and 45%, falling to 35% and 31% in 2018].

Nwando: Yes. So I'm going to start with the second. I'm going to have some corrections as we move forward.

That term "female genital mutilation" in my mind is an extremely offensive term. I don't use it.

I don't talk about it there. I don't even teach about it.

We're talking about female circumcision, so let's call it what it is. It's female circumcision.

Alice: I apologize. I'm listening.

Nwando: It is an extremely offensive term. I want to start and be on record as somebody who is against female circumcision. But having said that, there are certain things that we just need to understand about why it happens and why it will continue to happen. It's going to be an in-bred solution and not an outside solution.

Let's let me also talk about numbers. I'm not sure where you got your percentages from, 50% of women are not circumcised. The first time I ever heard about circumcision was when I came to the United States at age 20 something. "Who's making this stuff up?". I don't come from a society where this happens. There is no way under the sun that 50% of women are circumcised. I can't really speak as forcefully about Yoruba women, because that's not the group that I study, but I would be shocked if 50% of Yoruba women are circumcised.

Female circumcision has been brought up when it comes to citizenship, trying to sort of move justification for being granted asylum.

Female circumcision doesn't just occur in Africa. We have case studies essentially in many places of the world.

If there's anybody practising, it's going to be such a small percentage. I've researched Igboland since 1995, I have not come across it. But I do know that it happens because I had an aunt who was in the medical profession and what they were doing was going into the rural areas where it did happen to essentially teach women how to do it, but do it safely.

In terms of Africa, female circumcision tends to be a coming to age ritual.

And I'm not trying to convolute it with Islam or anything. I'm just saying female circumcision pre-colonial - let's leave out religion and all of that - it's a coming to age ritual. Young boys are circumcised around age 13. And so our young women, it's all about coming to age. Among the Kikuyu, they've come up with what they call a "circumcision of words". And that's why I was saying that any kind of eradication must be inbred because it's so rooted in culture.

What is circumcision? It's about not just the act of being circumcised, but it is an act of being elevated from girlhood to womanhood and all the things that we are taught about what it means to be a woman, what it means to be a mother and all of that.

It's a very touchy subject. I teach on women and gender, gender, and sexuality in Africa.

I never teach about circumcision. I remember when Alice Walker came out with "Possessing the Secret of Joy" [about an African woman who chooses to undergo circumcision], I'm like, "whoa, what is going on? Did she just make this up?" I remember reaching out to some of the most powerful African women that I knew, I said, "why aren't you challenging her? Why are you letting her keep perpetrating some of these false claims?".

And again, I started this by saying personally, I'm not in agreement and I want to see us move in a different direction. We have to do it with an understanding and it has to come from within as opposed to people sitting in the west and be like, "oh, I'm going to teach you".

African women have to decide in the societies in which it happens. Circumcision is something that is spoken about under closed doors, women talk to women. And that's what I got from the strong African women that I reached out to, to say, why don't you confronting this and there? And they said to me, "we're not exposing this to a Western gaze. It's not their business. We're going to have conversations about this. We're going to have these conversations within our societies", knowing full well that conversations around female circumcision don't even occur with men being there.

And so this is my reason, as an Africanist historian that works on women, gender, sexuality issues, I don't teach about this because I don't feel like I don't know enough. I know the book knowledge part of it, but I don't really know enough because I haven't experienced it in the ways that people that I know to be an authority in my mind to speak of it.

In my writing, I talk about "female circumcision". A lot of Africanists write about "genital cutting". I have a problem with "genital cutting" personally. There are many forms of female circumcision, the most form, which is only practiced in very small pockets of areas in Northern Africa, like in the Sudan, which is infibulation in essence.

In most forms of female circumcision, other than infibulation, nothing is cut. It is the scraping - much like the foreskin of the penis is cut during male circumcision.

I'm not trying to minimize. I'm trying to put this in historical perspective, why does it occur? It is not about denying women sexual pleasure. It's rooted in customs of coming to age.

It's been so politicized, it's almost gotten to a point where it's the West versus the rest of us. The west is the one dictating for African women what is problematic.

I put this hand in hand with the mutilation of the female body in the West, whether it's breast argumentation or a butt argumentation or straightening. Why aren't we calling that "mutilation"? And for me again, I'm I have a problem with both, right? So for me, it comes down to who has the power of naming, right? And certainly in this case, it's not, it's not African women naming this.

Pawnship

Alice: Pawnship - as I understand it - was the domestic institution of slavery. Many of those enslaved persons were women. Doesn't that indicate their greater vulnerability within the households, that they would be more likely to be enslaved?

Nwando: Africa is huge. I think that you're, in a sense, right. But I work on indigenous slavery in West Africa, mainly among the Igbo, and when you talk about pawn ship, it wasn't just women that were pawned, right? Everybody was, you know, male, female.

In the West African region - Cameroon, Nigeria, Ghana, the so-called slave coast - there are systems in which women marry a deity. It is mimicking this "female husband" phenomena in the spiritual realm. This form of slavery emerged as the result in response to the aftermath of the Atlantic slave.

So people, these communities had been so decimated right by kidnapping, wars, to recover individuals and human beings for the slave market at the coast. Right? So these societies were depleted. How did they look to essentially guard their communities and raise population? Deities, goddesses, and gods started to marry human beings. And who were the married women? These women became enslaved to the deity in the sense that they could not marry anybody else. They're married to the deity. And so it is a form of slavery, but it is a form of slavery that I argue in my work that elevates women's status.

Yes. They take away rights. But in certain instances - you are still enslaved - but your rights and your status in society and your power rises because of your association with a spiritual being that is so much more powerful than mere mortals.

And so they're looking at me like, how is that slavery? It is slavery because these women have been enslaved to that deity, which means that they cannot marry human beings. So that in itself means that their rights have been taken away. So it's almost like it's this conundrum of both taking away rights, but also improving rights.

So I don't know that I quite answered, but what I wanted to offer was just a little bit more information about how varied these experience experiences are in various parts of life.

Witch-hunts

Alice: Over the past two decades in Tanzania, 20,000 people have been estimated to have been killed as witches. Govind Kelkar and Dev Nathan argue that the transition from matriliny to patriliny actually exacerbated these witch-hunts, men seized elderly women's land. I was thinking that witch hunts are an example of women's vulnerability?

Nwando: I agree with you a hundred percent. I really do. It's not an expertise of mine. What I can say though is that when you look at African religions, there are these spiritual forces that are good forces and there also spiritual forces that are not good.

Caste

Alice: Caste was practiced by some African societies, they upheld rigid endogamy (women should marry within their ethnic group), hierarchy, and inherited occupations. Do you see any differences with African societies that practice caste and those that didn't, in terms of gender?

Nwando: That's an interesting question. I would actually argue that, for the most part, I don't see African societies as caste-based societies. Most African societies practise exogamy as opposed to endogamy. There are rules there to make sure that people are marrying exogamously. They don't want a lot of these in-bred diseases that might materialize.

When you look at the institution of polyandry, when a woman marries many husbands, there is still that insistence on exogamy. Whether you're talking about Nigeria or the Congo, they're still insistent that when a woman marries her first husband, the second husband cannot come from the same area as the first husband. And the reason, Alice, was about solidarity and alliances.

If the daughter marries exogamously then those two places are not going to go to war, to fight yourself. Principles were there also to create unifying influences between communities during the pre-colonial period.

Why are there so few women in West African parliaments?

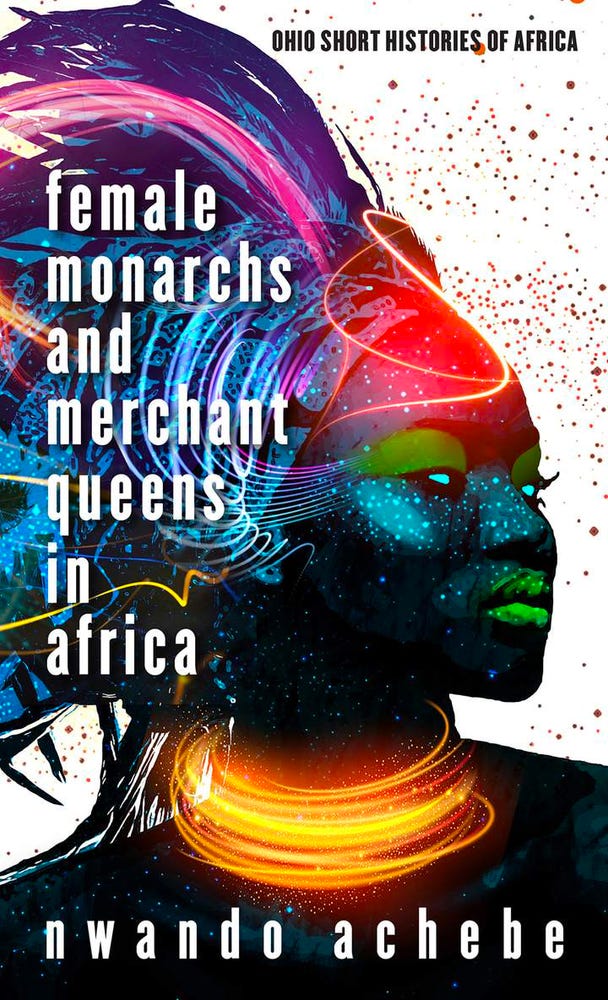

Alice: Your book shows [historical] examples of female leadership across the continent. But if we look at parliaments today, Southern and Eastern Africa have exceptionally high rates of women in parliament. But in West Africa there seems to have been a reversal of fortunes. Women only represent 16% of parliamentarians, just on average. What do you think caused this reversal of fortunes in West Africa specifically?

Nwando: It's painful to me, it's sad.

The only thing I can think of is leadership, right? Because what happened to West Africa happened to East Africa happened to South Africa, happened to all these other areas. So what is the difference now? These are societies, pre-colonially, where women were extremely powerful. And all of a sudden colonialism reduced women pushed us to the background. But we're in 2022 and enough of blaming colonialism, some other African countries have done the right things. So the only thing I could point to is it goes back to good leadership.

I think that it has a lot to do with the present nature of politics and governance, and who's in charge and our leaders actually making this a priority. In the areas you've mentioned, it's coming from leadership. The president of the nation is saying this is important.

Why that's not happening more in West Africa? Your bet is your guess is as good as mine. I'm not a political scientist.

Alice: I think I can trust you to tell me when I'm totally wrong and to correct me. I think we have that relationship. So can I share my little theory with you?

Nwando: I really want to hear this.

Alice: I totally agree with your point that leaders can choose to institute female quotas, even in West Africa. President Wade in Senegal - in response to feminist lobbying - he instituted a gender quota. So Senegal is now ranked 7th in the world for women in parliament.

That said, Nathan Nunn and Leonard Wantchekon's research suggests that transatlantic slavery may have exacerbated distrust and ethnic divisions. And of course it was West Africa that was hardest hit by the transatlantic slave trade because of its proximity to Jamaica, Virginia etc.

So today in Ghana and Southern Nigeria, women are still independently wealthy and powerful, but what I wonder is if the transatlantic slave trade exacerbated distrust and divisions, and on top of that the imposition of colonial borders compounded these effects: grouping multiple ethnicities into large states, imposing nationhood where there was none.

Religious diversity is another unique feature of West Africa. Nigeria has Muslims and Christians, and there is an element of religious violence in many of the countries along the Gulf of Guina.

What that means is even if women are powerful economically, it's very difficult to mobilize and create strong networks of national solidarity because you have all those ethnic divisions. So how can you mobilize for a genda quota? How can you mobilize as women for women?

Also, if ethnicity is politicized it may not be your priority to have a women leader. You'd rather have someone from your ethnic group, from your village, from your region. So your priority isn't necessarily "we want gender equality". We want representation in another way.

So my theory, and you should critique me, is that transatlantic slave trade exacerbated ethnic divisions and distrust and the imposition of colonial borders forced those religions to be part of the same country, which impedes women's mobilization.

Nwando: Phenomenal. 100%. Yes. Let me just add to that, because when you start, I'm like, "why didn't I think of this?" 100%, 100%.

Let's add to the fact that the other nations that we're talking about, different parts of Africa, they have less population density. In Nigeria alone, we have 512 different ethnic groups of people that speak different languages.

You have a very population dense area, with all these different ethnic groups, there is no such thing as a national identity.

When we talk about national identities, we talk about Tanzania. Why? Because Nyere... and Bibi Titi Mohammed (who a lot of people don't talk about, a Muslim woman that taught him that if you want to bring everybody together, speak Swahili and stopped speaking Queens English). So in Tanzania you have this national identity, you don't have it anywhere else.

If war breaks out today in Nigeria, there's no national identity. When somebody asks me "who are you?" The first thing that comes to mind is not that I'm Nigerian. The first thing that I'm going to say is that I am Igbo. That is my nation. Then I will tell you, I am a woman. This is how I define myself. Third, I will tell you I'm African. Then I tell you that I'm Nigerian.

So I agree. 100%. I think you're onto something big there. Yeah.

Final words

Alice: Professor Achebe, let me, let me hype up your book before we close. So this is "Female Monarchs and Merchant Queens in Africa". It is a glorious read. It's not like a heavy, boring academic tome. It's exciting. It's a joy! It was absolutely the best book I read of 2021. It is an enlightening and monumental book, Professor Acheb.

Nwando: Thank you. Thank you. Thank you, Dr. Evans for having me, this was fabulous. Thank you so much.