The Origins of States

What led to the emergence of states? What explains their timing and geography? Did peasants embrace state-protection or were they forced to stay put? Theories include:

Cereals - which could be hoarded and used to feed armies

Collective defence against nomads on the steppe

Military innovations (like cavalry and chariots)

Trade: stationary bandits collected rents and provided shelter

Moralistic punishment and pro-sociality enabled large-scale cooperation

Spatially concentrated resources discouraged exit.

Back in 1970, Robert Carneiro proposed ‘circumscription theory’. Groups battle for control over scarce arable lands, then the losers are compelled to submit because the ecological alternatives are too bleak. In some places, this seems obviously true - see my recent piece on Ancient Egypt. But is it valid more broadly?

David Schönholzer and Pieter François have a fascinating new paper which harnesses several ginormous global-historical datasets: the Atlas of World Archaeology, the Seshat Global Historical Databank, and pre-state agricultural productivity. And to paraphrase Sir Mix-A-Lot, I like Big Data.

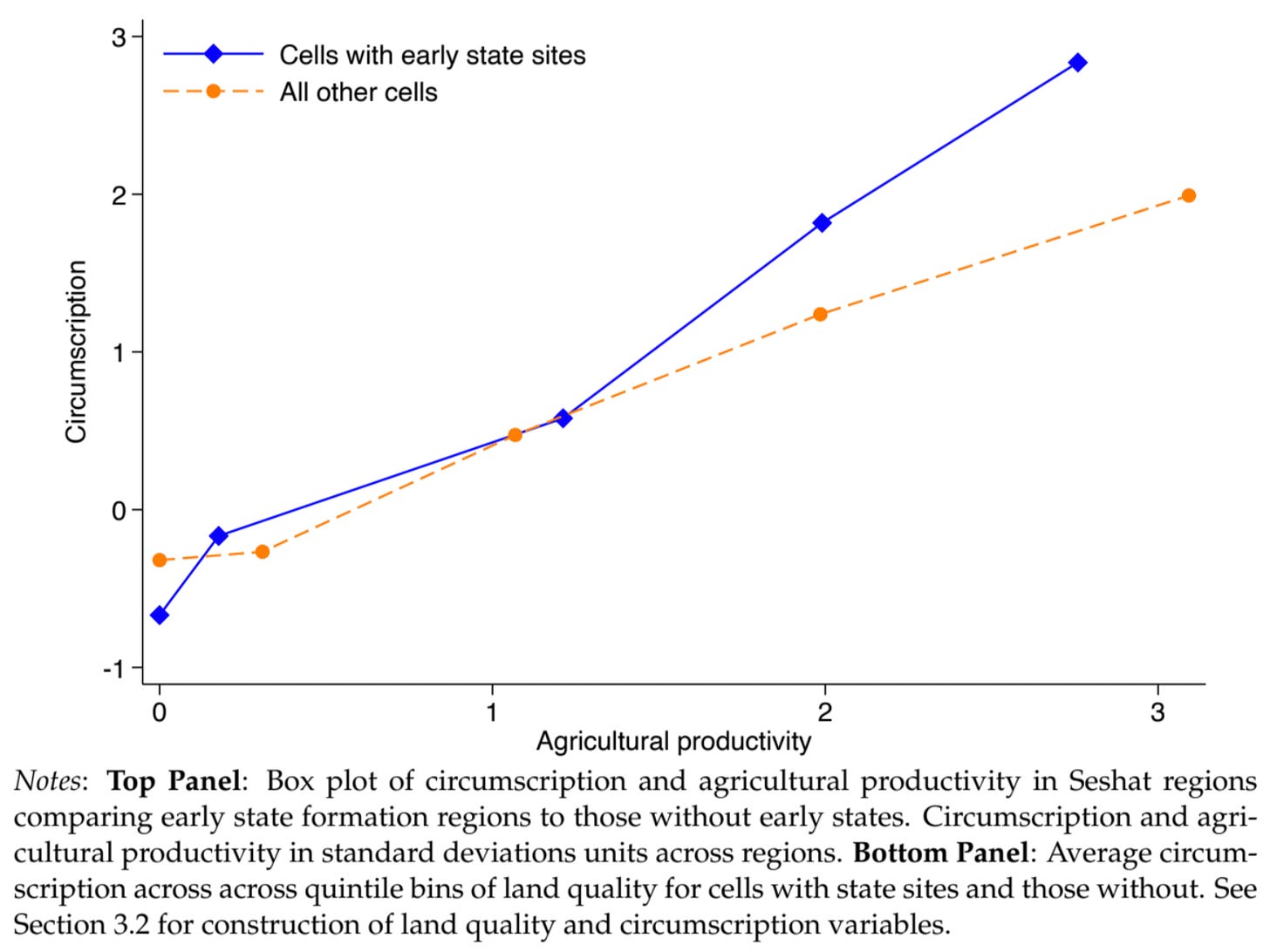

‘Circumscription’ is calculated by computing the difference between the productivity in a cell and the average productivity of all surrounding cells. Across the American Midwest and Western Eurasian steppes, pre-state agricultural productivity is pretty similar, so ‘circumscription’ is low. In the fertile Valleys of the Nile, Oaxaca, and the Basin of Mexico, by contrast, circumscription is high.

Circumscription is strongly associated with state formation

When resources are especially rich, you might - to quote Sir Mix-A-Lot - be ‘thinking about sticking’.

Cooperation or compulsion?

Schönholzer and François have created a tremendous timeline of early state formation (indicated by purple triangles). It showcases general trends and regional specifics. They use this to probe whether states emerged through cooperation or compulsion.

Organised warfare (e.g. defensive ramparts and professional armies) usually precede states. This is consistent with Turchin and colleagues’ argument that military advances enabled large empires. But, in the case of Egypt and the Kachi Plain, signs of intergroup conflict only emerge after state formation.

Public goods (food storage facilities, irrigation systems, roads, drinking water supply systems, or ports - shown in blue) appear before state formation in every single early state region.

Trade (orange circles) appears before state formation in all but two cases.

Population pressure typically precedes hereditary status (legal codes, organised religion and inequality).

’Hereditary status’ generally emerges alongside or after states. This casts doubt on Henrich’s theory that moralising supernatural punishment was a necessary catalyst of large-scale cooperation. Religion may have nonetheless provided a crucial role, subsequently, legitimising hierarchy.

All this validates Graeber and Wengrow’s claim that urban settlements do not entail hierarchy. Indus Valley Civilisation is a good example. No evidence has been found for elaborate tombs, individual-aggrandising monuments, large temples, and palaces. The archaeological evidence suggests egalitarianism.

Faster socio-economic change in circumscribed regions

Schönholzer and François compare societies that had long pre-state histories, alluvial agriculture and similar time since the Neolithic transition, but different degrees of circumscription.

In circumscribed regions (like the Kachi Plain), the domestication of crops is swiftly followed by trade, public goods (like irrigation), organised conflict and inequality. By contrast, in the Middle Ganges wet, where you could exit like a turbo vette, these phenomena took another 3000 years to appear.

Circumscription predicts cooperation and conflict

Schönholzer and François compare the characteristics of all non-state societies. They find that circumscription doesn’t just predict states, it predicts many kinds of conflict and cooperation.

Organised warfare, public goods, and trade were much more common among pre-state societies located in circumscribed regions.

These differences are just so… BIG! 76% of circumscribed pre-state societies had public goods, in contrast to 20% of comparison societies.

Food storage facilities were much more common in circumscribed regions

James Scott famously argued that appropriable cereal grains led to the rise of states. This has recently been corroborated by Mayshar et al.

However! Work by Schönholzer and François implies that theory is in trouble. The authors do not discuss it, but Mayshur’s correlation may be spurious. People in circumscribed regions were much more likely to build public goods (like food storage facilities). It is precisely these places that saw the emergence of states.

Social dynamics therefore may be much more important than cereals versus tubers.

1/5 pre-state societies were hierarchical

Social stratification (‘hereditary status’) does not systematically vary between circumscribed and non-circumscribed pre-state societies. Schönholzer and François do not discuss this but personally, I’m hooked and I can’t stop staring.

20% of pre-state societies were hierarchical.

Graeber and Wengrow thus appear incorrect to claim that states locked in inequality. Hierarchy, while uncommon, sometimes preceded states.

Furthermore, hierarchy appears just as frequent in ecologies with great exit options and those with terrible exit options. My interpretation? Rulers may have enforced oppression through ideological persuasion.

I’ve got to be straight. I don’t think the evidence is sufficiently strong to rule out material mechanisms - especially since their datasets exclude fishing and pastoralism. Moreover, absence of evidence should not be confused for evidence of absence (especially if it concerns something that happened five thousand years ago).

But I think this indicates humans’ tremendous power of cultural innovation.

A Cooperative Fraternity and Coerced Captives

I must lodge one objection…

Schönholzer and François frame ‘coordination and compulsion’ as a binary. Were states imposed by force or did people choose to cooperate?

But as the girl in the Old El Paso commercial says, “Why not both?”.

Merchant citizens may have cooperated as a privileged fraternity, while forcibly subjugating women and slaves.

Athens, for example, was a direct democracy, comprising all male citizens. Each had the right to voice his opinion and debate at length. Boozy parties facilitated group bonding. Men reclined on couches, all at the same level. The Athenian wine vessel below depicts this egalitarianism. Women and slaves, meanwhile, were subordinated. So Schönholzer and François’s binary of ‘coordination vs. compulsion’ omits a crucial aspect of early states: the capture and coercion of slaves and concubines.

TLDR!

David Schönholzer and Pieter François’ brilliant new paper suggests that states were neither imposed by elites, entailed by crop type, nor enabled by organised religion.

Cooperation, conflict and state formation all seem to have emerged much more quickly and more typically in rich ecologies with weak exit options.

Apparently you other brothers CAN deny human rights to women and slaves.

Writing in the 1300s, Ibn Khaldun paid a lot of attention to the idea of in-group solidarity as the main phenomenon that sustains a state. He discussed geography and waterways, too, but it is interesting to think of circumscribed regions as having both the material conditions as well as the sense of being hemmed in that can create in-group solidarity.