Big Questions, Big Data!

Research Ideas!

“We need to come and collect you, I’m afraid the road is badly damaged”, warned my host in Madura (a beautiful island in Indonesia). Crossing the colossal bridge, you are initially welcomed by smooth tarmac, and it all seems perfectly congenial… But the further you venture, the bumpier your ride. Potholes, craters, and ditches force a meandering slow-mo, before eventually it’s just rubble.

My brain - in all honesty - is much the same. Despite my best efforts to study global cultural evolution, there are muddy patches.

But perhaps you can help me tackle these gaps? Here, I’m especially eager to trace people’s digital footprints - the little clues they leave while living their lives online. How can brilliant computer scientists leverage massive advances in machine learning to study cultural change? Allow me to present some ideas:

How does the Caste System change upon Migration?

Did Saudi Arabia’s export of Wahhabism change the Islamic world?

Can We Track the Great Gender Divergence on TV?

How Might we Measure Cultural Flux in Autocracies?

What’s the Impact of Religious Schooling?

How does the Caste System change upon Migration?

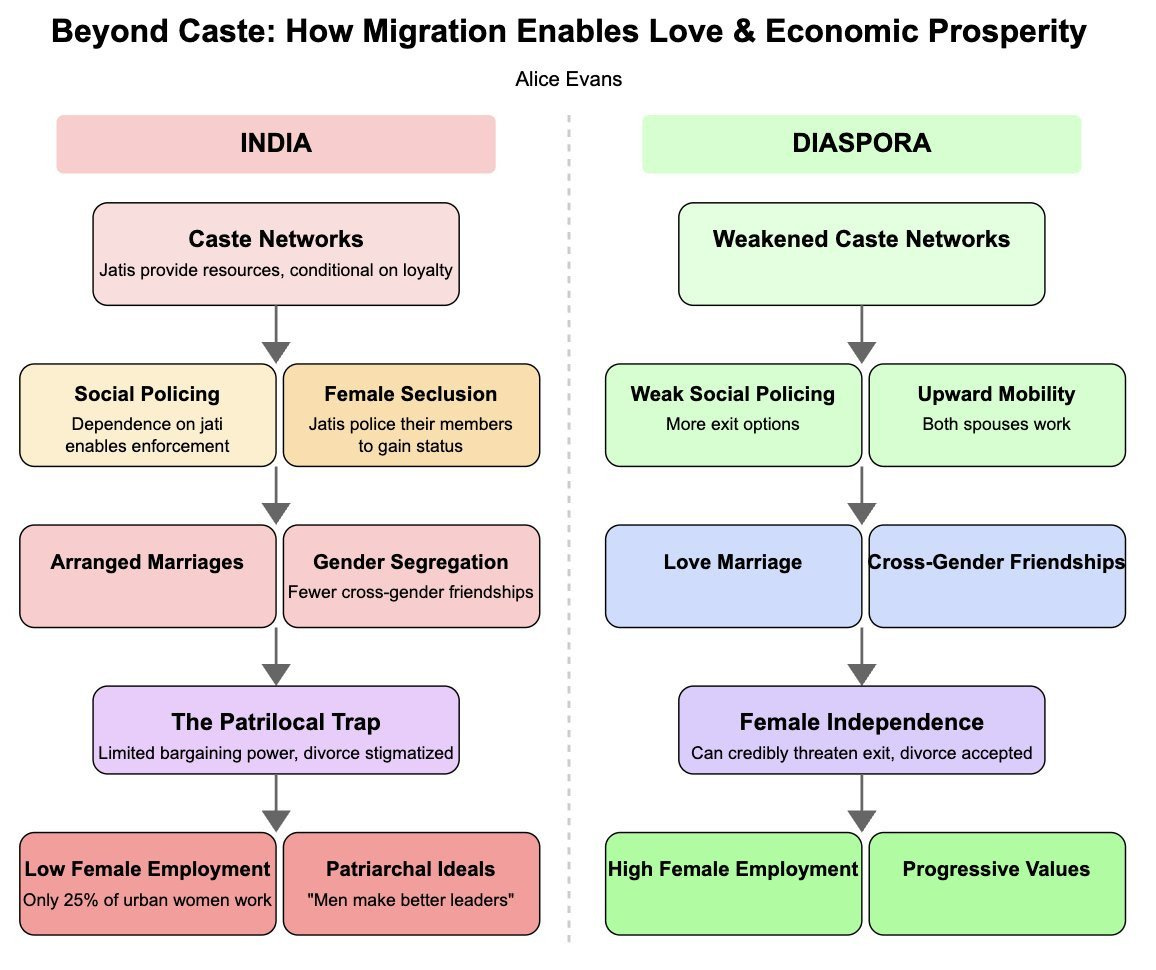

My hypothesis is that India’s ultra-low female employment and ultra-low divorces have emerged from the caste hierarchy, jati policing and Islamic legacy. Indians tend to secure trusted networks of cooperation by raising their children to marry within jati. This motivates arranged marriages and strict policing. Since jatis gain status collectively, by emulating upper caste ideals of purdah (“Sanskritisation”), many uphold strict policing and suppress female mobility. This effect is strongest in North-Central India, where Muslim rulers raised the prestige of female seclusion.

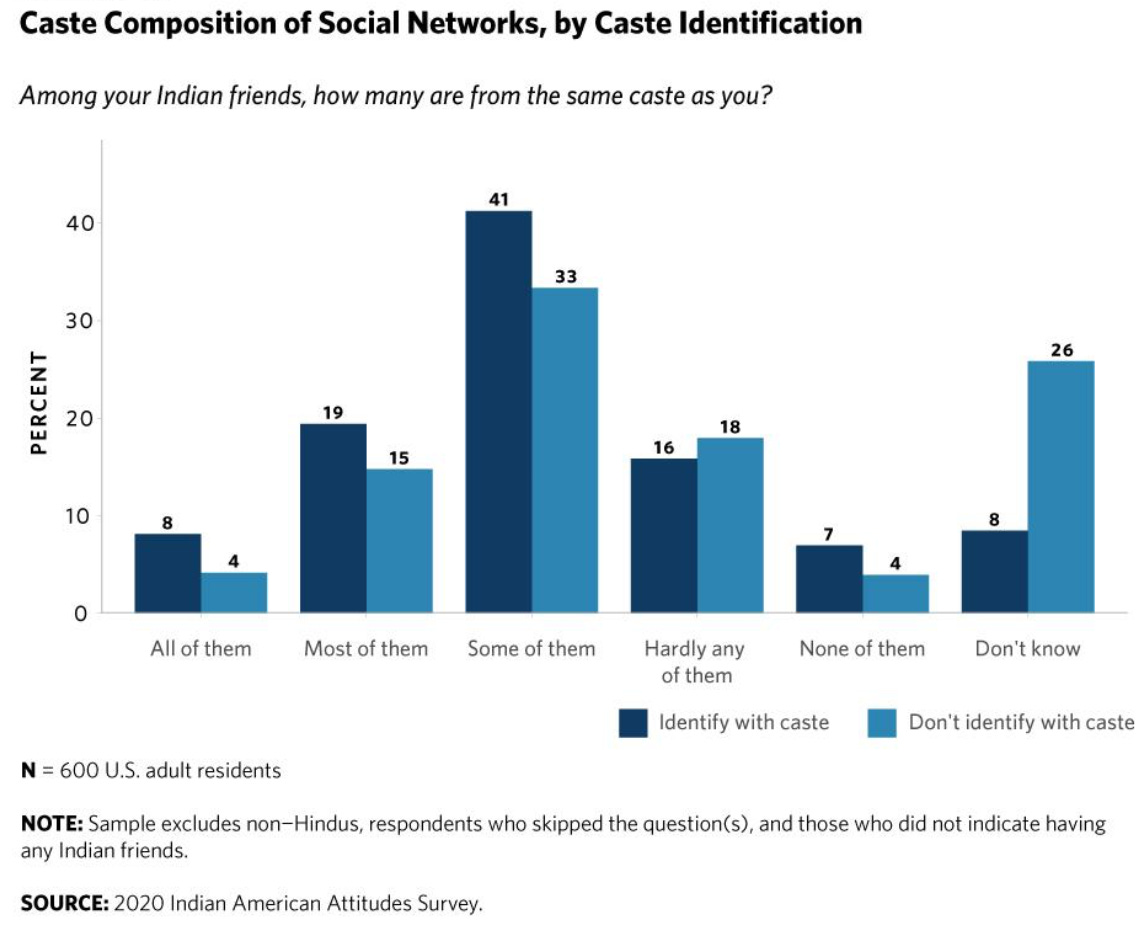

Yet the Indian diaspora - from the UK to Malaysia to Mauritania - is totally different - showing high rates of female employment, less religosity and declining significance of caste. 32% of Indian Americans said that “they do not personally identify with a caste”. The share is much higher among the second generation. Moreover, Indian Americans tend to celebrate a range of festivals, including US Independence, Christmas and Valentine’s.

What explains these differences?

Drawing on my globally comparative research, I suggest that as Indians move to different economies, they can do business with a broader set of partners, and are no longer beholden to a singular jati. Indian Americans usually say their friends are diverse, rarely from their own caste. In Southall (UK), for example, one Sikh trader shared that he sources from at least 30 different traders, of diverse ethnicities. With so many prosperous connections and exit options, jatis may lose their power to police. If families are no longer fixated on endogamous marriages, young women may be permitted greater freedoms. Simultaneously, families can secure status by investing in education and prioritising upwards mobility.

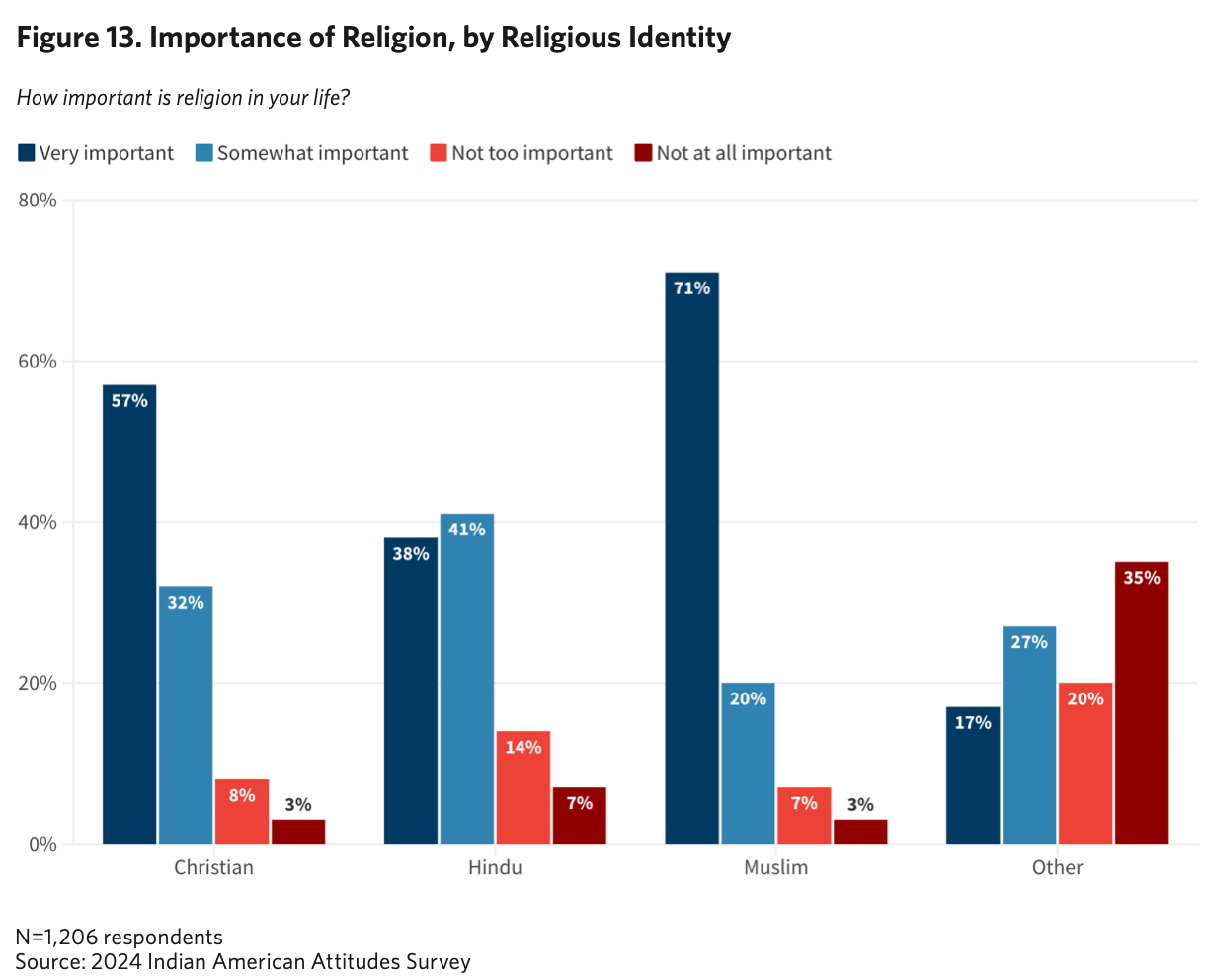

Why do only 38% of US Indian Hindus describe themselves as “very religious”, compared to 71% of US Indian Muslims? I suggest that Hindus never developed religious education for the masses, so seldom carried this institution overseas. Nehru - the Secularist - explicitly to prohibit divisions and imposed strict proscriptions, rejecting religion in government schools. Religion is instead expressed through devotional chants at temples, H-pop songs, big festivities (like Holi), family rituals (like Raksha Bandhan), and online gurus. Hindu faiths haven’t really developed educational institutions. But there is one exception, which proves the rule: Bali. Here in Indonesia, the Hindu minority seeks to preserve their faith by inculcating it in schools - stoking the fire.

On the other hand, survey responses could be misleading. Eager to appear more progressive, upper castes elites may be overstating network diversity. Further, if Hindus continue to internalise ideas of purity and pollution, or if upper caste groups predominate, they may still discriminate. Soumitra Shukla studies US and European multinationals hiring in India, and finds significant caste bias. It would be wonderful to see replications within the West.

Research ideas:

Leverage big data from Meta to map connections across the Indian diaspora. Using surnames to identify caste, estimate intra-caste connections and marriages.

Why do British Hindu and Sikh women work at high rates? Does this also hold within the US? Speculatively, I hypothesise that jati becomes less significant overseas, thus families permit greater female freedoms, including love marriages and higher female employment? One might explore these correlations through large-scale surveys - within the US, UK and Malaysia.

Why are Indian Hindus and Muslims similarly religious, but US Hindus are much more secular? One could test my hypothesis by comparing children’s after-school enrolment in religious education both within India and the diaspora.

In Britain, Hindu and Sikh women are just as likely to work as work as white British women. Families prioritise not Sanskritisation through purdah, but upward mobility through education and wealth. By contrast, British Muslim families typically rely on a single male earner. How do different cultural values affect upward mobility and neighbourhood prosperity?

Compare migrants from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia - countries which share similarly high rates of religosity, alongside low female employment. What percentage enrol their children in religious education (either full-time or as an after-school club). How does this vary by religion?

How did Saudi Arabia’s export of Wahhabism change the Islamic world?

Wahhabism is a distinct Islamic sect, urging strict adherence to the Quran and Hadith, purging all other innovations (bid’a) and polytheism (shirk). Under the principle of “al-wala’ wal-bara”, you should show loyalty (wala’) to true believers while actively disavowing (bara’) and distancing oneself from disbelievers/ polytheists/ innovators. This includes Sufism, worship of saints and shrines, as well as birthdays and Valentines. Importantly, Wahhabism isn’t just a set of theological beliefs, but a mandate to ostracise other Muslims for deviations.

Ever since the 1960s, Saudi Arabia has leveraged its oil wealth to propagate Wahhabism worldwide. By funding mosques, madrasas and religious scholarship, KSA globally denigrated Sufism, while ostracising non-Wahhabi Muslims, disavowing corrupting influences and innovations.

Empirically, we have a wealth of qualitative and historical studies, but these are rather piecemeal, like discrete research on an elephant’s tusks, tail and trunk. We really need to understand the interconnections of financial and cultural flows.

Based on my globally comparative research, I anticipate huge effects. Imagine there are two equilibria:

In “A”, Wahhabis are extremely niche and generally ignored. Since they’re the minority, they can’t threaten others with ostracism. No one cares.

“B” is Wahhabi-majority. They organise politically and have the resources to create club goods. Wahhabi bullying works, since everyone seeks status and social approval.

Saudi funding for Wahhabism likely shifted the equilibria from “A” to “B”, which then allowed endogenous processes of “al-wala’ wal-bara”, loyalty and disavowal. This could help explain the post-1970s Global Islamic Revival.

Causality may be a little murkier, however. Some aspects of Wahhabism have been adopted by other sects. Just like warfare, there’s inter-group competition: clerics from each sect extol religious education, telling parents that they will be Judged for any such failure.

Research ideas:

How much money has Saudi Arabia spent on proselytising? This includes flows to mosques, madrasas, as well as funding scholarships at the Islamic University of Medina (IUM).

Can you digitise historic Wahhabi syllabi at the Islamic University of Medina via OCR, then use track diffusion in madrasa curricula or local fatwas?

Track Islamic discourses over the past 50 years using Natural Language Processing on digitised fatwas, sermons, and books (e.g., from Al-Azhar vs. Medina libraries). Measure shifts in keywords like ‘bid’a’ or anti-Sufi rhetoric.

Explore the demise of Sufism via shrine destructions, surveys on adherence, or conflicts. Proxy with Google Images/satellite data, detecting pixel shifts in destruction, correlating with financial flows or return IUM scholars.

Can We Track the Great Gender Divergence on TV?

Someone clever could explore whether cross-national differences in television content contributes to divergent rates of female employment. This would likely require:

Building a comprehensive corpus of popular television scripts,

Undertaking a content analysis with natural language processing,

Constructing a ‘Progressive Index’, comparing across cultures, and then

Tracking the lagged rate of female employment.

Drawing on my globally comparative research, I have sketched likely charts. Correctives welcome!

Can we Track Cultural Flux in Autocracies?

Kevin Hart, Pete Davidson and Zarna Garg are all performing next month at Riyadh’s comedy festival. MBS is engineering top-down cultural change by imprisoning dissidents and making secularisation appear more permissible and prestigious. But are Saudis really laughing? Or is he stretching the boundaries of permissibility?

One could use surveys, but I worry about non-responses and social desirability bias. Eagerly, I went to the Saudi Embassy, requesting permission to undertake qualitative research. Alas, they never replied. Not easily defeated, I must change tack… Can we leverage people’s digital footprints to track their revealed preferences?

Research Ideas:

Examine social media metadata. Harnessing GPS locations, hashtags, computer vision and sentiment analysis, you could track the vibes. On Snapchat, you can search for posts by location.

Use streaming data (from Netflix and Spotify) and book sales to track what stories and ideas are gaining popularity. Apply Natural Language Processing (NLP) to book reviews and comments.

Track consumption data - e.g. rising demand for women’s workwear and athleisure.

What’s the impact of religious schooling?

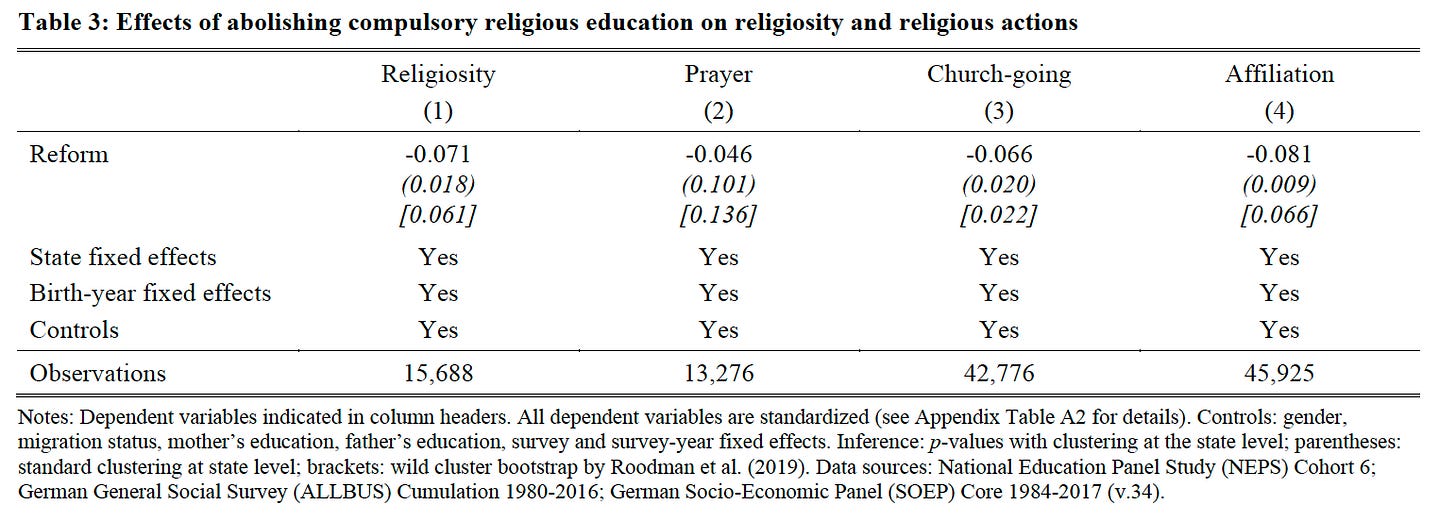

The 1949 Constitution of West Germany made religious education compulsory, exposing state high-school graduates to a 1,000 hours of religious education (quadruple the time they spent learning physics). Between 1972 and 2004, this obligation was progressively weakened, with states permitting students to study non-denominational ethics. What happened next? Aold, Woessman and Zierow find students then became less religious, less likely to pray, or attend religious services.

Indonesia mirrors this same trend, as the growth of religious schooling spawned demand for religious politicians, campaigning to uphold the faith. In Sub-Saharan Africa, European-run missions appear to have increased educational gender equality and female household autonomy. In Kerala, competition between religious and secular groups may have amplified female enrolment.

Belief in Heaven, Karma or nirvana may motivate young people to forgo economic returns in exchange for salvation. I call this “The Paradise Premium”. In my research in Leicester (a city in the UK), every Muslim I interviewed enrolled their children in after-school madrasas. Does this have any impact on female employment, upward mobility, or the broader macro-economy?

How might we test this empirically? This is tricky - disentangling cause and effect. Religious parents are doubtless more inclined to enrol their children in faith schools - so as to preserve their own values over the generations. How do we tackle endogeneity?

Research ideas:

Peer match students using observable characteristics, then follow long-run outcomes. One might compare Gujarati Muslim and Hindus in Leicester, noting their religious education, time spent on home-work, expressed priorities, and long-run economic outcomes.

How do after-school religious schools impact the macro-economy?

Suppose the government relaxes restrictions on faith schools/ clubs, permitting more establishments. How does this affect long-run economic activity, especially of women?

Caution! When comparing faith and secular schools, recognise that there can be ‘de facto’ faith schools. Suppose an ecological disaster forces a large Buddhist population to relocate as refugees. In host communities, some schools may become predominantly Buddhist, despite being designated as ‘secular’.

Puzzles!

Madura is a glorious island with abundant delights, but poor infrastructure limits people’s capacity to harness these resources. Just as great roads would aid connectivity, I’m hoping that LLMs can help us connect the dots and trace global cultural evolution at scale.

Thank you for being so patient while I’ve been away doing qualitative research across five regions of Indonesia. These big trips are hugely important, as they enable me to understand cultural change on the ground. Truthfully, it was tremendous and there is much to come…

Extremely well researched and quite amazed the depth of coverage by this author who I noticed for the first time at CNN. 🙌🌟

Just glanced through this post.

New Zealand has experienced 2 pulses of 'Indian' immigration in my life time. It would be interesting to compare the NZ life paths of Indians in each of these 2 streams, especially for those people in each stream who immigrated about the same time.

The first pulse was following the first coup in Fiji when indigenous Fijians encouraged the offspring of Indian indentured labour (mostly Tamils) who dominated local businesses, both large and small, to leave Fiji. ie they had been somewhat selected for 'business' success. The second pulse has been directly from India and has been mostly post NZ's adoption of a 'points system' for immigration qualification. This has, somewhat, selected for 'academic' success.

My subjective impression is that Indians immigrants, especially children and grandchildren born here, are quite thoroughly assimilated into NZ society. Though perhaps this is because their numbers have been too small for them to form distinct ethnic enclaves.