Power & Punishment

A reply to Acemoglu & Robinson

Nobel laureates Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson have a brilliant new paper, published in the Journal of Economic Literature, proposing a dynamic interaction between culture and institutions. They suggest that a society’s values legitimise particular economic and political institutions, which then shape emergent configurations of culture. In their theory, each cultural set has a set of ‘attributes’ (which can be abstract or specific). These sets can be ‘free-standing’ or ‘entangled’.

Let me give a cheeky hypothetical and suppose there’s a culture of ‘Daronism’. Its attributes include high productivity, churning out books and papers on Economics, which are well-regarded and widely-cited. On the one hand, these attributes are highly ‘entangled’ (core to Daronism), but they are also quite abstract and open to modifications. So as these thinkers consider new data and arguments, they move from stressing institutions to embracing culture.

Contrasting cultural evolution across world regions, they suggest that Islam has some ‘highly specified’ attributes, which are also ‘entangled’. Sharia reigns supreme, since it is the word of God, revealed by Mohammad. Given this fundamental set of attributes, reinterpretation or critique becomes illegitimate. Instead, Muslims usually gravitate to scriptural literalism, and the religion thus becomes relatively ‘hard-wired’, less open to contestation or institutional reform. Rulers then cement their authority by invoking and entrenching Islamic values.

Are Acemolgu and Robinson correct?

Descriptively, they deserve an applause - no one else has really explained why Muslims are especially religious and tend to support Sharia. But is their explanation compelling? Let me raise a set of theological, historical and theoretical questions:

What about Judaism? The Torah is also considered to be the direct word of God, as revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai.

Judaism and Islam are theologically very similar: strict codes were enforced with threats of violent punishment. Just as Jewish men are obliged to study the Torah, Muslim men must attend Friday prayers. Scripture is repeatedly sexist, legitimising sexual slavery. Judaism and Islam are share tight prescriptions for rituals, dress, male circumcision, food (kosher/ halal), while prohibiting image-making and pork.

But Orthodox Jews are now a minority. European Jews embraced the Enlightenment, and over the 20th century, US Jews rapidly integrated and secularised. In fact, Judaism may have accelerated America’s secularisation. Almost all the pioneers of the US’s feminist movement were Jewish. So, I’m not convinced that we can pin Islam’s rigidities to the Quran being the word of God.

Hasn’t Islamic culture undergone major contestation?

Before the 20th century, many Southeast Asians and Sub-Saharans self-identified as Muslim, but nonetheless revealed their flesh, while worshipping shrines and ancestral spirits. Muslims have actually shown remarkable flexibility in moving from syncretism to scriptural literalism. Contrary to A&R, many Muslim communities were not under sharia, but rather have become so. Why?

What about punishment and prestige?

When Acemoglu and Robinson focus on specific cultural attributes, they are primarily considering widely-shared beliefs and practices. But this seems to omit community enforcement.

Since everyone seeks social approval within their networks, they are highly sensitive to praise or punishment. Suppose a man is chatting with a group of female colleagues, who express extremely progressive views. He may nod along so as to maintain social inclusion. Alternatively, consider an Evangelical homosexual - he truly believes it is wrong, but nevertheless succumbs to temptation. In both cases, fear of community punishment plays a hugely important role in motivating compliance.

Ostracism, shaming, bullying, mockery and ridicule are all publicised penalties, signalling that such behaviour will get you kicked out. Uniting against offenders, communities show what is unacceptable. Since we all seek status and social inclusion, visible threats spur widespread conformity.

It is my contention that even in states conquered by Islamic armies, Muslims’ behaviour was not ‘hard-wired’. While individuals may hold certain beliefs, they may still be swayed by deviant desires (“sheitan”).

Islamic rulers and jurists then devised religiously-sanctioned state apparatus to enforce righteous behaviour, commanding right and forbidding wrong (hisba). This was intently political, strengthened by conquerors whose legitimacy was especially insecure. Seljuk and Mamluk rulers established offices of hisba to prove their piety, consolidate authority, and punish detractors. States then set a precedent, legitimised by ulama, encouraging wider vigilantism, safeguarding society from damnation.

Today’s essay is a struggle between Acemoglu and Evans. Reader, you play the judge!

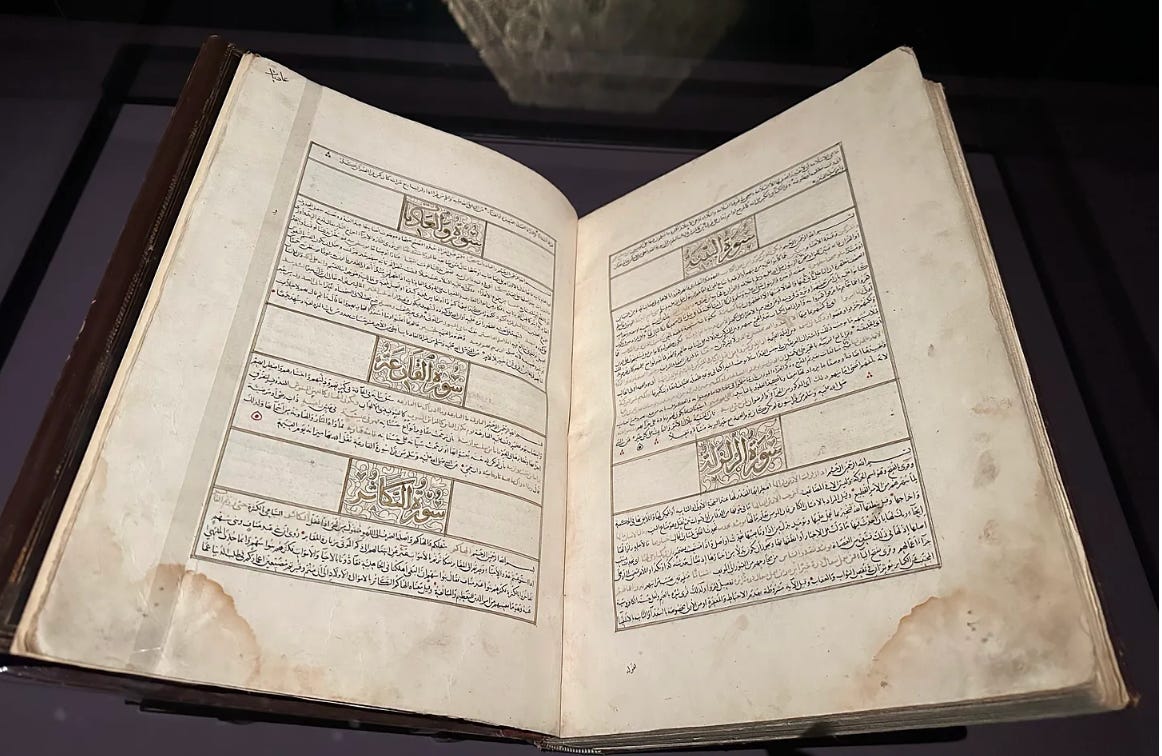

Commanding Right and Forbidding Wrong

“Commanding good and forbidding wrong” (hisba) is a Quranic duty (3:104), but it has always been contested, as scholars debated who should enforce it (the state, men, women?), it scope (public or private?), and its intensity. Women shouldn’t even have autonomy over their lives, so how could they police others? - some argued. Early Islamic scholars, as Michael Cook explains, did not emphasise state enforcement. Even as hisba became a state office, opinions varied on whether they should police behaviour behind closed doors.

In the early centuries of Islam, ordinary primarily encountered the state through the market inspector (muhtasib). Under the Umayyad and early Abbasid caliphs, this role focused on checking scales, measures, and produce quality. By the 9th century, the office grew increasingly religious, tasked with commanding right and forbidding wrong. In 930, Caliph al-Muqtadir’s attempt to appoint a police chief as muhtasib in Baghdad was overruled for lacking religious affiliation, underscoring rising piety. Conversely, the Buyids (ruling Persia, 934 to 1062) were far less interested in piety. Their muhtasib in Baghdad, Ibn al- Ḥajjāj, gained infamy for his obscene poetry about visiting prostitutes!

Evidently, religious policing was not set in stone, but mediated by the ruling authorities’ wants and capabilities. In the 1500 years of Islam, religiosity has always been a tussle, always a fist-fight!

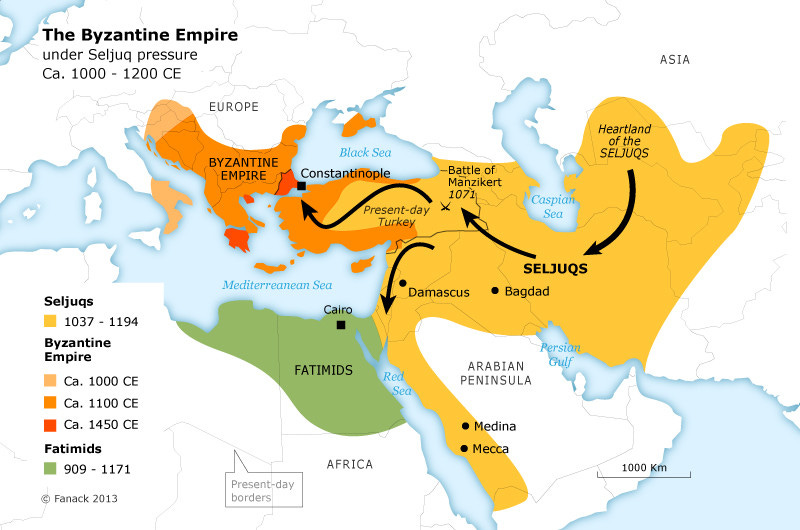

Seljuqs

In the 11th century, the Seljuk Turks stormed into the Middle East. Despite military success, their power was precarious amid Fatimid and Isma‘ili rivals. Culturally distinct as nomads, they were only superficially Muslim, retaining pre-Islamic practices like drinking and gender mixing. If you peruse museum exhibitions on the Seljuks, you’ll see ceramic tiles and bowls depicting women with loose air, often playing musical instruments.

Seljuq sultans sought to solidify control by performing piety, presenting themselves as true Sunnis. Poets hailed the sultan as the ‘muhtasib of the kingdom’, instilling justice with strict penalties, physically carrying the switch (dirra). Royals also embraced ‘siyāsa’, meaning both good government and also punishment.

Strategically, rulers strengthened the office of hisba, to expand government influence and censor public morality. The Siyāsatnāma, a Seljuq administrative text, urged rulers to station muhtasibs in every town, calling hisba a “foundation of the kingdom”. The title derives from ‘ihtasaba’, meaning “to try to gain honour in God’s eyes by acting righteously”.

The Seljuk muhtasib, aligned with state power, administered ḥudūd (statutory) and ta‘zīr (discretionary) punishments. In Ghazna, a muhtasib publicly flogged an powerful emir and army general for drunkenness.

Public shaming parades (tashhīr) were introduced, with the offenders’ crimes loudly announced to all. In 1152, a muhtasib’s deputy in Baghdad whipped a disgraced madrasa director. In 1074–75, prostitutes were paraded on donkeys and banished; in 1119, a secretary was flogged. Blasphemers were also punished by tashhīr.

Seljuq muhtasib encroached into the private sphere, developing espionage and surveillance. By the late 12th century, they spied from rooftops or employed ruffians to raid households, targeting Isma‘ilis and Shi‘i sympathisers amid geopolitical threats. In 1150, a Baghdad preacher, Badīʿ, was arrested for suspected Shi‘i leanings; his home raid revealed clay tablets inscribed with the twelve Imāms’ names, leading to public beating and parading. A decade later, Shi‘i artisans faced muhtasib-led humiliation. In Syria, hisba zealously safeguarded “the saved group” of Sunni orthodoxy, arresting and parading heretics. Patronised by the state, the Sunni ulamā were very much emboldened.

The Seljuks were certainly not alone in using moral policing to legitimise their rule. Indeed, as their empire fragmented, new powers emerged, again seeking to consolidate their rightful authority.

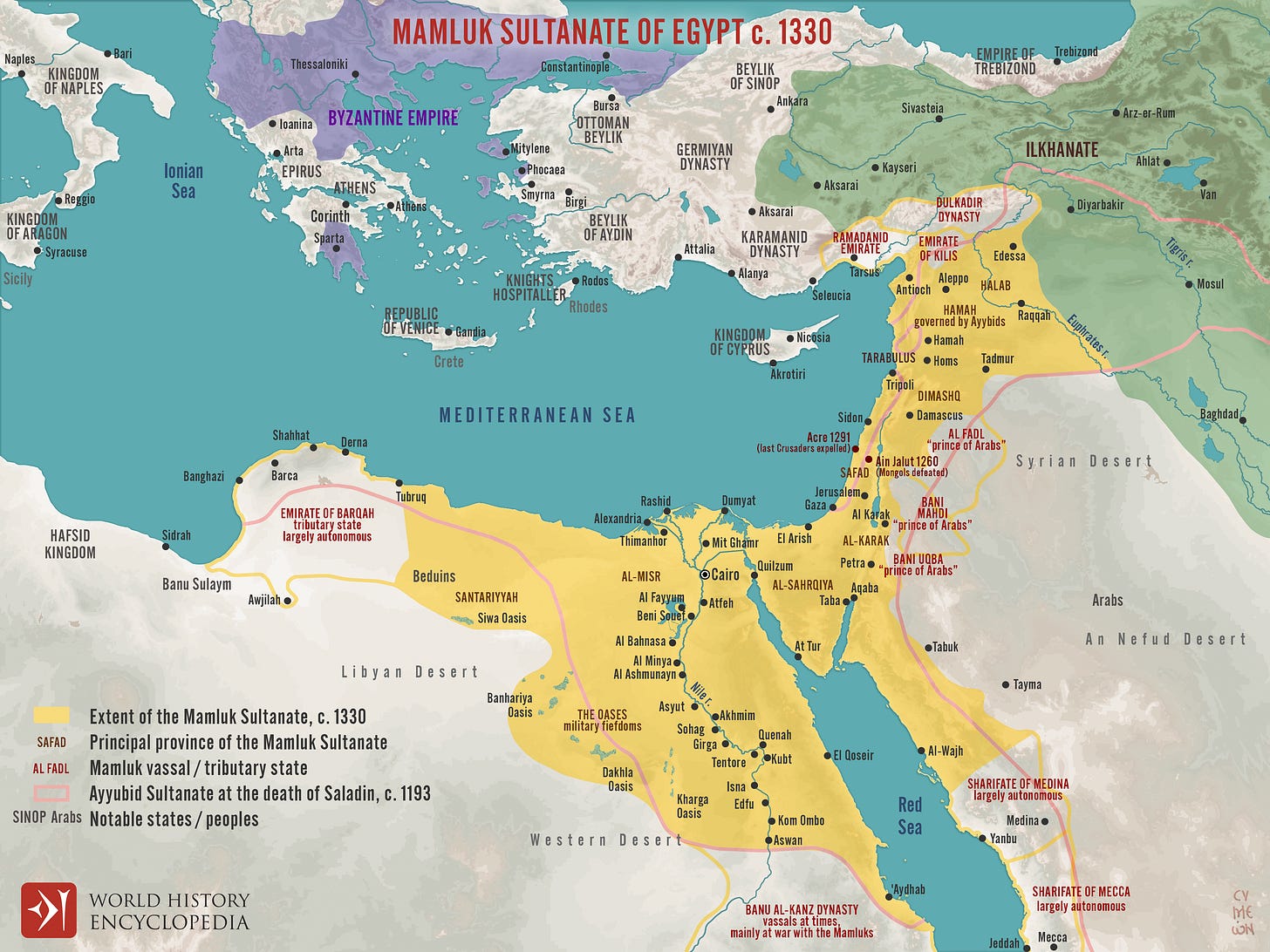

Mamluks

The Mamluks were a dynasty of slave-soldiers who seized power in Egypt and Syria in the 13th century. Lacking both religious and ancestral legitimacy, their Islamic credentials were weak.

To demonstrate piety, Mamluks positioned themselves as guardians of Mecca and Medina, leading the annual pilgrimage from Cairo and exclusively providing the Ka‘ba’s covering. Sultan Qalāwūn compelled the local Meccan tribe to swear that only the Mamluks could supply it, ensuring their banner was displayed above all others. Patronising Jerusalem and the Dome of the Rock, the Mamluks reinforced their role as defenders of the faith.

The Musée d'Orsay currently has a fantastic exhibition on the Mamluks: below you can see their patronage of Mecca and Medina.

Fiqh jurisprudence was well-established. Rather than each person independently interpreting scripture for themselves (ijtihād), the proper path was established by eminent jurists (taqlīd). Doctrinal policies were enforced via muftis answering queries, judges assessing legal issues, and the sultan’s siyāsa power dispatching orders.

The muhtasib acted as the state’s primary arm - directed by rulers, guided by fiqh, patrolling public spaces to command right and forbid wrong.

What was punished and policed?

If you’re eager to read 12th century texts, Egypt’s dry climate is actually a God-send, keeping them well-preserved. Amazingly, we can read al-Shayzari’s manual, Nihdyat al-Rutba fi Talab al-Hisba (The Utmost Authority in the Pursuit of Hisba). Yet more miraculously, I found an English translation. Wahey!

It details mandates, justified by the Quran and the Prophet’s endorsement, with stern vigilance around gender mixing. Following Michael Cook, let me suggest that this constant policing implies that norms were not ‘hard-wired’ into people’s brains, but had to be continually enforced through punishments. The following are direct quotes from the 12th century manual:

Cotton carders: The muhtasib must forbid them from allowing women to sit by their shop doors waiting for the carding to be completed, and from talking with them. (p.89)

Flax spinners: They must not allow women to sit by their shop doors…. But God knows best (p90)

Shoe makers: They should not use paper, felt and such like to make women’s slippers so that these squeak when the women walk, as the women of Baghdad like to have them. This is shameful, and is a disgrace which does not befit free-born people. The muhtasib must therefore stop them being made and worn. But God knows best (p.93)

Money changers: To make a living out of money changing is dangerous to the religion of those engaged in it… If he comes across anyone practising usury, or doing anything while changing money which is not permitted in Islamic law, he should chastise him and evict him from the market (p.94.

Slave-traders: Anyone who wants to buy a female slave may look at her face and palms, but if he asks to examine her in his house and be alone with her the trader must not allow it unless there are other women present. [Nice evidence that slaves typically veiled in public] (p102)

Boys’ education: The first thing that the educators should teach the boy is the short chapters of the Qur’an… Then he ought to acquaint him with the orthodox articles of faith, the basics of arithmetic and whatever letter writing and poetry is considered appropriate, excluding the foolish and depraved varieties…

The educator should order any boy who is over seven years old to pray with the congregation, because the Prophet said: “Teach your children to pray when they reach seven, and when they are ten, beat them if they neglect it.” The educator must also order the children to honour their parents and to obey them without hesitation, to greet them and kiss their hands when they come into their presence..

“The educator must not teach a woman or a female slave how to write, because this makes a woman worse, and it is said that a woman learning to write is like a snake made more venomous by being given poison to drink.

The educator must stop the boys from memorising or reading any poetry of Ibn al-Hajjaj,’ and should beat them if they do. This also applies to the poetry of Sari‘ al-Dila’’ as there is nothing good about it. The educator must similarly not acquaint them with any of the poetry composed by the Talibi Rawdfid.* Rather, he should teach them the poetry which eulogises the Companions’ so that he fixes this in their hearts” (pp119-120) [This is a great example of censorship. Ibn al-Hajjāj was a Baghdadi poet, whose work was often satirical, irreverent, or obscene. ‘Ṭālibī Rawāfiḍ’ is a derogatory term for Shi‘i groups, meaning ‘the rejectors’]

Jews and Christians: The muhtasib should stop them from riding horses… Their buildings should not be higher than those of the Muslims nor should they preside over meetings. They should not jostle Muslims on the main roads, but should rather use the side streets. They should not be the first to give a greeting, nor be welcomed in meetings… They must not be allowed to recite the Torah and the Bible openly, to ring the church bells, to celebrate their festivals or to hold funeral services in public (p. 122) [A good illustration of reducing non-Islamic prestige and preventing competition]

Alcohol: If the muhtasib comes across anyone drinking alcohol he should give him 40 lashes with the whip....If it is a woman, he should whip her while she is wearing her [head] covering and clothes” [Good indication of veiling]

Fitna: If the man committed [pre-marital] adultery, the muhtasib should whip him in public, as God said: “and let a party of believers witness their punishment”.’ If it is a woman, he should whip her while she is wearing her covering and clothes. As for the adulterer who has consummated a marriage, the muhtasib should gather the people around him outside the town and order them to stone him, as the Prophet did with Ma’iz.

If it is a woman who has consummated a marriage, the muhtasib should dig a hole for her in the ground, sit her in it up to her waist, and then order the people to stone her, as the Prophet did with the woman from Ghamid. If the evildoer has committed sodomy with a boy, the muhtasib should throw him off the highest point in the town. (p.125) [All these punishments are to be highly public, so as to unite the community against the offender]

If the muhtasib sees anyone.. playing a musical instrument, he should chastise him.., after breaking the instruments. The muhtasib must do likewise if he sees an unrelated man and woman consorting together, either in private or on the road (p.126) [Proscription on male-female friendships].

The muhtasib must inspect the places where the women gather... If he sees a young man alone with a woman or speaking to her about something other than a commercial transaction, and looking at her, the muhtasib should chastise him and forbid him from standing there…The muhtasib must also inspect the preachers’ gatherings. He must not let the men mix with the women and should put a screen between them. When the gathering disperses, the men should leave first and go on one road, then the women should leave and take another road. The muhtasib must chastise any youth who stands in the women’s road without good cause.

If a funeral procession takes to the streets the muhtasib should order the women to walk behind the men and not to mix with them. He must also order them not to bare their faces and heads when they are walking behind the dead, and instruct the town crier to announce this in the town. The most important thing, however, is to prohibit women from attending the burial.

Whenever the muhtasib hears of a woman who is a harlot or a singer he should call her to repent of her sin. But if she returns to it, he must chastise her and banish her from the town.

He must do likewise with effeminate men and those who have no beard, well known for their perversions with other men. The muhtasib should forbid an effeminate man from shaving off or plucking out his beard and from going amongst women. This also applies to anyone who could have a fine beard and yet goes without one, for when he shaves his beard off this is a sign of his depravity and the muhtasib must chastise him for doing it” (p.127).

Now here’s a specific instance of policing. In 1422, Cairo and Fustat were adorned for the grand annual pilgrimage caravan, which began at the Citadel and wound through vibrant city streets before embarking across the desert to Mecca. Women would might arrive early the day before, securing the best spots to view the caravan, possibly mingling with men during the day, then staying overnight to keep their place. But the muhtasib feared fitna, and issued a strict decree banning women from lingering near merchants’ shops in the marketplace to watch the procession.

However, women nevertheless attended. Again, this suggests that Egyptians were not passive conformists. The spectrum of permissibility was partly a function of how sternly deviance was punished and policed.

Prestige!

Male honour was thus contingent on female seclusion, to such an extent that women’s names were omitted so as not to bring shame. The Musée d'Orsay features many beautiful objects belonging to royal women, yet unlike men, their names are omitted. The fragmented comb below is instead inscribed with the phrase, “among that which was made for the elevated veil” - signifying the status of total seclusion.

The Musée d'Orsay emphasises that royal women could still amass wealth and status - Sitt Hadaq was a slave of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun, then became superintendent of the harem and founded a mosque. My reply is two-fold: yes, royal women were wealthy, but the really crucial variable is the prestige of seclusion.

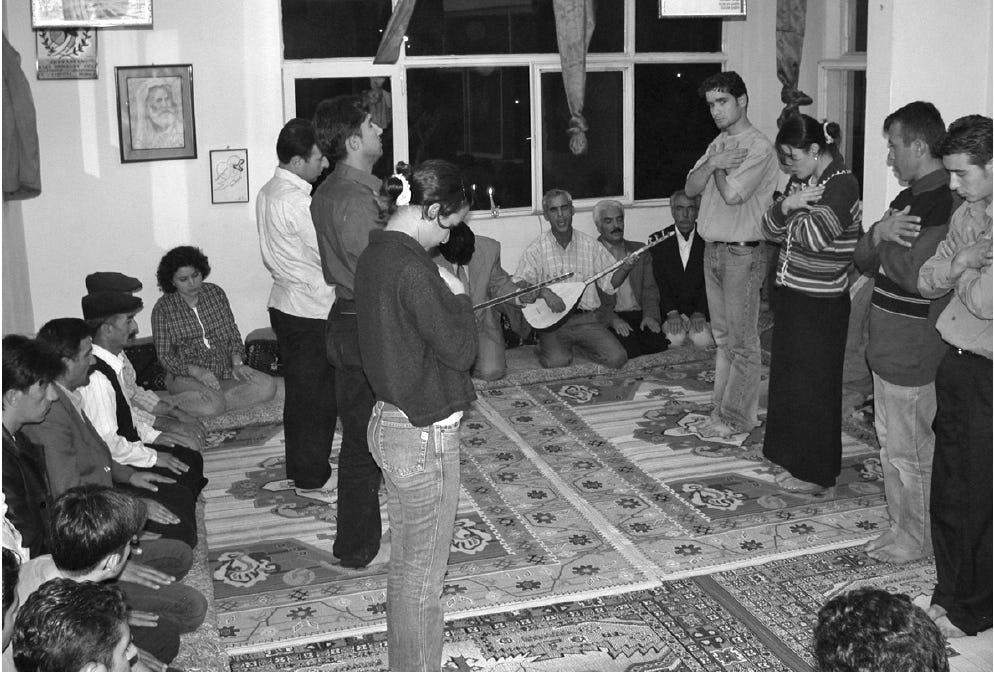

Ottoman Persecution of Alevis

Hisba was often politically driven (and that’s no different from Medieval or Early Modern Europe). Ottoman Sultan Selim I (r. 1512–1520) targeted Alevis - a sect blending Shi‘i, Sufi, and pre-Islamic customs, seen as threats backed by Safavid Persia.

As sultan, he created a register of all Shiites aged between 7 and 70, then in Tokat and Samsun his army beheaded, stoned or drowned them to instil terror. Persecution continued, with the Bektashi order banned in 1826 and later massacres in Maras.

Why does this matter?

In Turkey today, Alevi Shiis (versus Sunni) men are much more likely to endorse gender equality, and Alevi women are much more likely to work. In Alevi ‘Semah’ rituals, women and men dance together (as shown below). This reflects greater liberalism, without strictures of female seclusion. Without violent repression, this more gender equal sect could have achieved greater prominence and popularity.

West Africa

14th - 16th Centuries

Islam spread across Africa’s Sahara, savanna, and rainforests, per Michael Cook, because rulers valued Muslim’s literacy and trans-Saharan trade (especially firearms and warhorses).

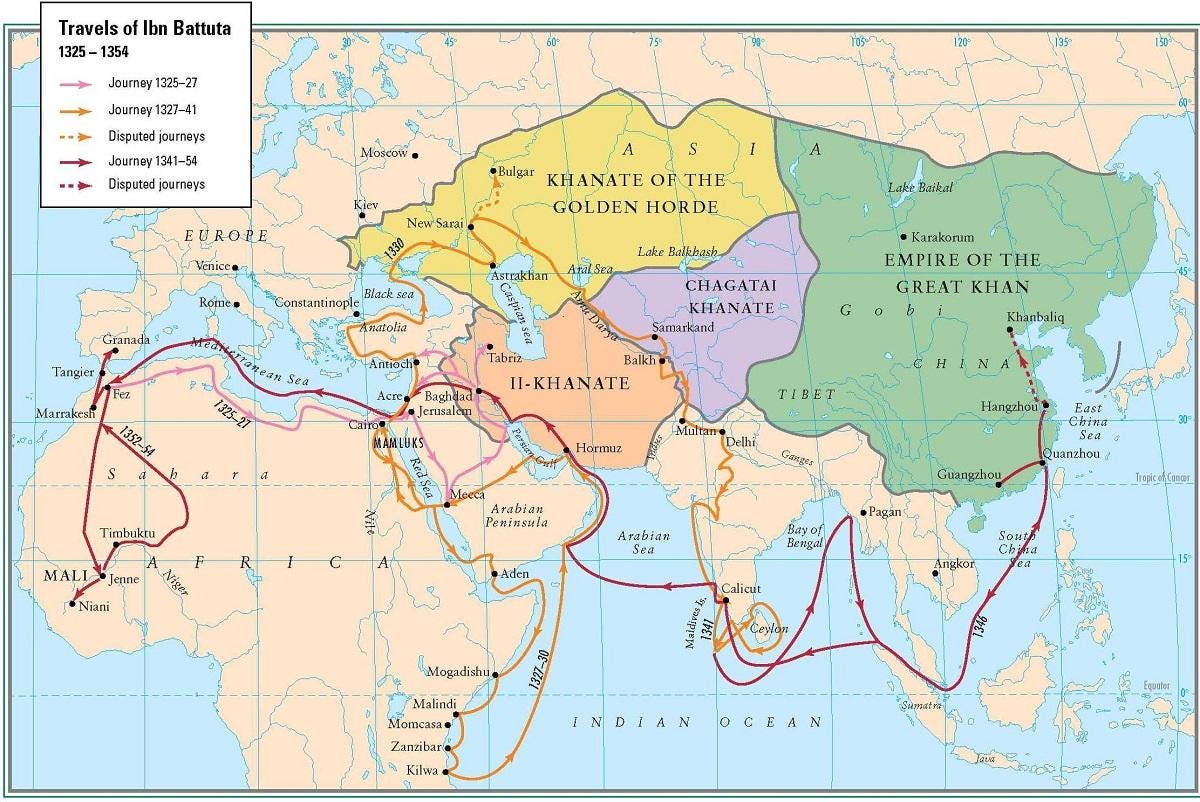

Yet they usually maintained native customs. Ibn Battuta, visiting Mauritania and Mali in the 14th century, was troubled by men’s lack of sexual jealousy, and women’s immodesty. A 150 years later, the Muslim ruler of Songhay bemoaned that beautiful young women (including judges’ daughters) often walked around his capital stark naked.

After Muhammad Askia seized control of Songhay in 1493, he undertook the Hajj pilgrimage and expanded his empire. To strengthen religiosity, he consulted jurist al-Maghili. Correspondence reveals subjects identified as Muslims but practiced paganism, sacrificing to trees and stones.

This duo aspired to enforce hisba, citing the hadith: “At each century’s start, God sends a renewer of religious understanding.” Al-Maghili urged jihad: “These people are polytheists… Holy War against them is more meritorious than against non-Muslims not professing the Shahada”. For those mixing paganism with Islam, he deemed them “tyrants and wrongdoers,” justifying Askia’s jihad as “most meritorious.” Force was vital: “Struggle against them with the sword until they all enter under your authority, in obedience to God and His Apostle”.

But waging jihad was seriously difficult - amid limited military and communications technology. State control was extremely weak, with local princes taxing trade routes but little else. Al-Maghili’s reply to Askia suggests widespread banditry.

“[When] we say to them ‘How then do you join up with these warmongers?’ and they reply ‘We are not able to go against them; we fear us, and that if we leave (them) someone else will seize us, because we are poor, (and) unable to defend ourselves”.

If one cannot contain warlords, one can hardly command right and forbid wrong.

How was Islam practised before the Sokoto Caliphate?

By the 19th century, most Saharan tribes had converted to Islam, yet but neglected Sharia and sexual puritanism. Islamist reformist and caliph of the Sokoto Caliphate, Shehu ‘Uthmān dan Fodio (1754 –1817), wrote several manuscripts detailing corrupt deviations. His Naṣā’ih al-ummat al-muḥammadiyya criticises:

Men and women’s open socialising;

Women traveling without husbands/ guardians;

Bridal feasts with women dancing before men;

Inheritance by the strongest or matrilineally..

He added, “The third party… commits mortal sins: not veiling women, mingling genders, depriving orphans, exceeding four wives. Their doctrine is corrupt… The disobedient is an unbeliever, damned eternally”.

Of course, I was very excited to read these original texts, as they are important for my ongoing debate with Daron! Let me make 2 points:

These deviations echo Muhammad Askia and al-Maghili’s concerns 300 years earlier. I suggest that their attempts reforms failed due to weak state capacity..

Shehu ‘Uthmān’s jihad overthew Hausa rulers, establishing a caliphate based on Sharia. Now we see, Islam is not ‘hard-wired’ but varies tremendously depending on who is in power.

Modern Northern Nigeria

Fast-forward to the 21st century, policing continues. In the late 1990s, Islamist politicians and ulama criticised secular capitalism, promising that religious reforms would unlock Allah’s blessings. Voters were persuaded, and 12 Nigerian states adopted sharia law.

Thousands of youths soon volunteered as enforcers, forming neighbourhood groups with sticks and whips, apprehending suspects. In Garon Dutse, a man interrupted a couple talking in public, “Don't you know we have Shari'a?”, then slapped the man. Muslim youths attacked peers for violations.

To regain control, Kano state established a vast hisba apparatus, organised at state, senatorial, local, village, and community levels. By 2015, over 10,000 Yan Hisbah (muḥtasibuun enforcers) were on the government payroll. A weekly radio programme Muryar hisba (voice of hisba) urged Muslims to command good and forbid wrong.

But Muslims are by no means monolithic! Hardline Islamic scholars attacked the government for leniency, while more Sufi-ulama and Muslim entrepreneurs pushed to protect local jobs.

Yan Hisbah arrested Muslim filmmakers for bringing male and female actors together on set. In 2021, Kano State Hisba banned mannequins as ‘idolatrous’ for being human-like and flaunting female figures. That same year, Hisbah Commandant General condemned hijab-wearing Shatu Garko for being crowned Miss Nigeria.

Muslims face the brunt. In 2003, a wedding was disrupted as “immoral”: a vigilante hisbah brigade brandished knives and sticks, beating up guests, smashing musical instruments. Police held them briefly, releasing without charge. Christians moved away.

In Zamfara, the state aims to enforce sharia, such as by prohibiting men and women from travelling together in buses, taxis and motorbikes. Hisba stopped local taxis, forcing women to disembark, while flogging drivers. Some then refused to carry female passengers. On buses, women were forced to sit at the back. Over 2000 motorbikes were seized by the police - sparking protests by drivers who wanted to preserve their precarious livelihoods. In 2002, 21 Christian nurses were suspended for refusing to wear an Islamic uniform.

Violent punishment has circumscribed the permissibility of dissent. In 2000, Shehu Sani, a Kaduna human rights director, was arrested and intimidated for critiquing Sharia; some called for his execution. The following year, Islamic clerks opposed their conference and threatened to unleash violence if it went ahead. Today, Northern Nigerian academics, activists, lawyers and women’s rights organisations tend to express criticism of Sharia in private, but not in public. Strategically, northern state governors have delegitimised a broad range of critiques as ‘anti-Islam’.

A Kaduna Muslim shared his view of self-censorship:

“Deep down, people are fed up with Shari'a. But Muslims are ashamed to say ‘we don’t want Shari’a’. There is no room for explanation about why we are saying no. In Zamfara, saying no to the governor is like saying no to Islam. Challenging the government is like challenging Islam. If there were a secret vote, the ‘no’ would win, but people won't come out and say so…

There is a fear of being misunderstood, so people keep quiet. They would be seen as blasphemous.

It was a deliberate deception from the beginning. In real Shari’a, you should be able to challenge openly, for example to say to a governor: ‘where did you get that shirt from?’. They don’t want that”.

East Africa

After Sudan’s National Islamic Front (NIF) seized power in 1989, it criminalised ‘indecent and immoral acts’, then established the Popular Police to ‘strengthen Islamic morals’. Authorities flogged, beat and fined women for their clothing, interactions, and work - 40 lashes for wearing trousers and knee length skirts.

In 2008, Khartoum police (reportedly) brought 43,000 public order charges against women. In 2009, a southern girl was arrested and whipped 40 times for wearing ‘shameful clothing’ - some local journalists objected that it should only be 20 for minors. After President Omar al-Bashir was ousted via a coup, the law was repealed and many Sudanese women expressed delight in newfound freedoms:

“It’s a new day, we thank the justice minister and civilian government,” said Awadia Koko, the head of the food and tea makers association in Khartoum. “We were subject to too much violence under the Public Order Law, we were tired of the insults, fines, humiliation and even killings associated with the law”.

“Basically it was designed to chase women from middle to lower class backgrounds, limiting their movement and their ability to make free choices.. Racism was another element –targeting women and men from marginalised ethnicities” - Sudanese activist Winnie Omer.

Authorities would “literally hunt women” - activist Hala al-Karib.

Peace was short-lived. Ongoing civil war leaves 12 million people displaced, many facing famine, ethnic cleansing and sexual violence.

A Reply to Acemoglu

Acemoglu and Robinson propose that each culture has a set of attributes, and if highly specific and entangled, the culture will then be more hard-wired.

Complementing their brilliant theory, I have sought to illustrate how culture may be sustained by punishment. While believers (of any ideology) may sincerely believe that X is wrong, they may still fall prey to temptation. Community persecution plays a crucial role in keeping us all in line.

In states conquered by Islamic armies, values were not only enforced by mosques and madras, but also by the state office of ‘hisba’. Perennially, societies were policed into a narrow band of permissibility. Where Islam spread via trade, clerics lacked state power of enforcement, and thus remain more syncretic.

Theorising more broadly, I contend that the great engines of cultural evolution are power, prestige, and punishment:

When one faction gains state power, it can institutionalise its values.

Prestige encourages wider emulation, since we all seek status and social approval. Prestige can also be impacted by non-state actors - e.g. conquest/ philanthropy/ ideological persuasion.

Punishment, ostracism, shaming and violence teach us what to avoid.

States are pivotal: extracting taxes then channelling resources to patronise preferred organisations and ideals; designing a curricular that elevates certain worldviews; while judges penalise behaviour they dislike. Technology is equally catalytic, allowing for persuasion and policing at scale.

Finally, it is with great excitement that I’m heading to Indonesia!! If you’d like to meet, please shout (or send an email).

Further Reading

Adamu, Fatima (2008) “Gender, Hisba and the Enforcement of Morality in Northern Nigeria”

Mikhail, Alan (2020) “God’s Shadow: The Ottoman Sultan Who Shaped the Modern World”

MS Evans - re the Islam vs Judaism comparison, there is one essential aspect of Judaism that is left out of your comparison, that is, the importance of rabbinical interpretation of the Torah since ca 500 BCE, and relatedly, the predominence of the 'oral Torah' and the Talmud over the written Torah. For almost one and a half millennia, the Bible has been seen as a difficult and often contradictory text that cannot be followed without interpretation and often, adaptation to a contemporary context. The Enlightenment surely built on these tendencies but it does not by itself explain the inter-religious differences you emphasize.

H. Gordon

Excellent analysis Alice as usual, the question that follows is how do we move out of this cycle of punishment and moral policing and would economic independence and self sufficiency for women and marginalised communities be enough in these communities? Also are there any examples where this has happened?