Why is Scandinavia the Most Gender Equal Place in the World?

Part 2

In 1900, Scandinavia was no more gender equal than the rest of Europe or North America. While women’s movements lobbied for suffrage, the majority were still scrubbing floors, washing laundry, and lacking status. However did Scandinavia surge ahead, outpacing us all?

Continuing this two-part series, I suggest that weak ideals of seclusion and a stronger culture of associations enabled high female employment, alongside labour mobilisation. Combined, this empowered the Social Democrats to wield state power for egalitarianism, wage compression, and proportional representation.

Here I draw on a wealth of evidence from economics, history, political science, as well as my qualitative research - a month in Stockholm plus interviews in Stavanger, Copenhagen, Lund, and Malmö.

Dual Earners

Claudia Goldin famously posits a U-shape relationship between female employment and structural transformation: as economies transition from agriculture to manufacturing, women drop out, avoiding stigmatised work, only returning with the growth of careers in services.

Yet Scandinavia was different: female employment was precociously high and thereafter quite stable. Why didn’t it plummet? I suggest they never idealised seclusion, and thus seized all jobs!

In the late 19th century, 55% of Swedish women were in the labour force - estimates Jakob Molinder. Even when Sweden was the exact same wealth as the Netherlands, Swedish women more likely to work.

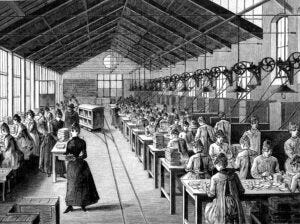

Initially clustered in domestic service, women then moved to higher-paying unskilled work in factories, where were generally welcomed by Swedish workers’ associations.

Here’s a crucial point for political economy: women’s proclivity to work, combined job-creating economic growth and democratisation ensures a BIG working class that can extract larger concessions!

Members also gained vital democratic training - learning self-governance through practices like voting, debating, writing minutes, holding speeches, and collaborating on social projects. In 1889, women matchmakers protested against low pay and dangerous work, thereafter forming the first women’s trade union.

Segue: in my qualitative research in Zambia and India, I noticed that domestic workers are often more meek than other similarly low-skilled women. Alone all day, labouring for a boss, without a reverse dominance coalition, many endure abuse, while being unaware of critiques that circulate in busy markets and factories. It’s very hard to organise or believe in the feasibility of social democracy if you lack allies.

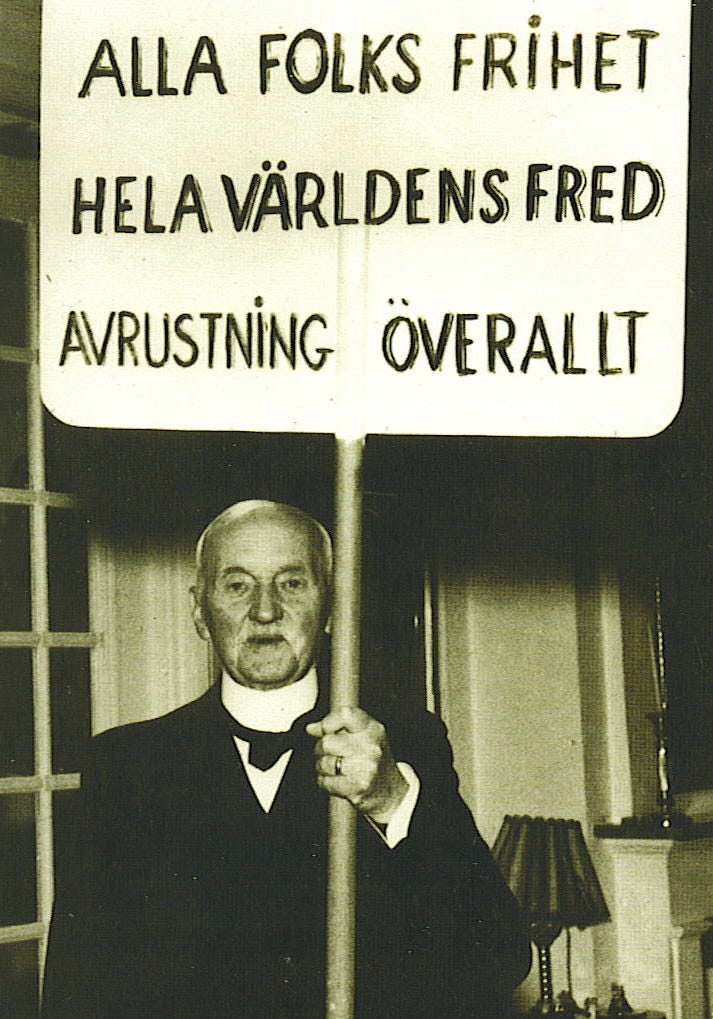

Protective legislation (such as against women’s night work) was imposed across many economies in the early 1900s, as formalised in the 1906 Bern Convention, but in Sweden this was bitterly contested. While some politicians sought to conform with international agreements, women’s rights organisations and sympathetic male politicians argued that this was deeply unjust, reminiscent of guardianship laws. Sweden’s Legal Committee specifically rejected the proposal, with Lindhagen (1909) arguing that

“it cannot be considered advantageous or flattering to us to be included in the finale of this male chorus of a dying masculine culture… We can still be the first in employment protective legislation, to place adult men and women at each other’s side as comrades”.

While night-work was banned, women textile workers and journalists kept petitioning through the 1930s, demanding its repeal.

20th Century Popular Movements

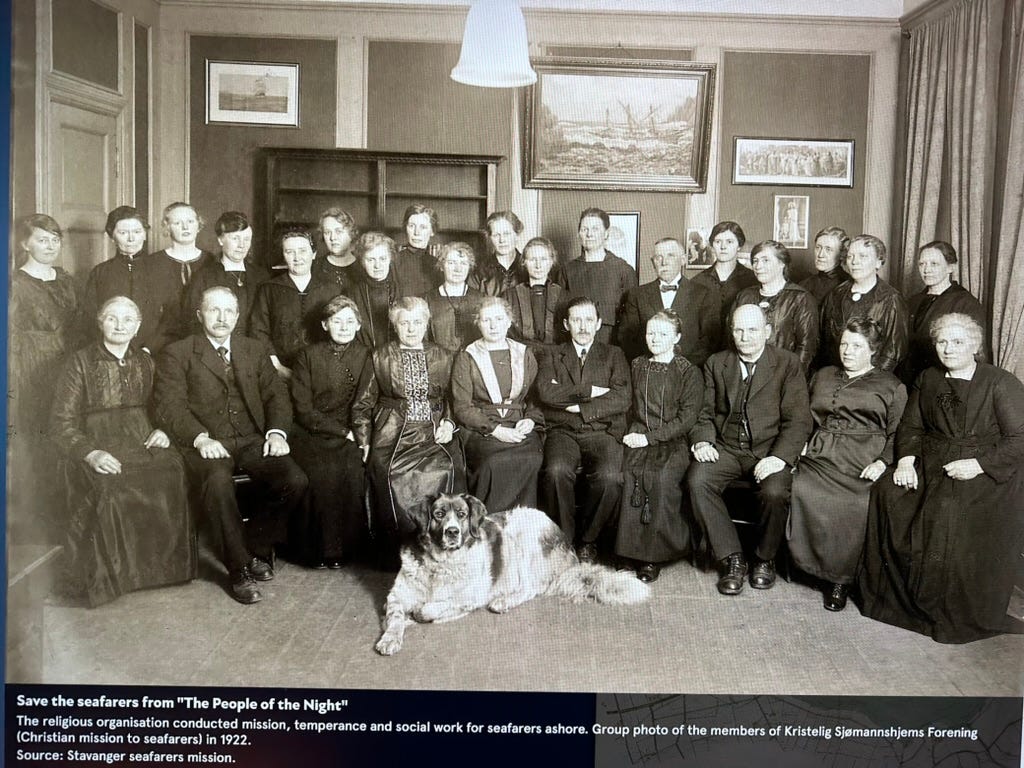

“My mother and father were part of associations - to get dairy, timber, roads, electricity, to get expensive machines”, explained Vera (78, born into a poor family in Northern Sweden). She continued, “the basic structure is not built from the top, it’s built by associations, free associations, built by people themselves”.

By 1920, one in four Swedes above age fifteen belonged to some form of association - whether it was labor, temperance, or free church organisation. These groups were diverse, yet shared a crucial feature: they championed both individual independence, collective action, and democracy.

Members comprised an ‘elective community’ - creating their own rules of admission and expulsion, establishing new hierarchies, and forming powerful ties of reciprocity.

In Scandinavia, membership of folket (‘the people’) became the determining principle of the right to social insurance. The state was seen as responsible. The first major reform forged in this pattern was the Swedish state pension adopted by Parliament in 1913. The Swedish welfare system continued to target resources and policies at individual citizens. This was in keeping with a cultural ideal that the state should protect the individual from being in a relationship of dependency - on parents, spouses, or charities.

School children were taught a history of Sweden that emphasised medieval traditions of independence. Odhner’s “National History Textbook for Elementary Schools” (1877) criticised aristocratic attempts to impose feudalism, and portrayed figures like Engelbrekt as champions of the peasantry, “[giving] ordinary Swedish people back their freedom and independence”. Proud histories of the 13th century were thus called upon to champion a particular vision of Swedish modernity!

The Swedish model thus contrast with the German welfare system, which worked through intermediaries (entirely consistent with the Catholic principle of Subsidiarity). It also contrasted with the United States’ antipathy to state interference.

Working Class Activism

Industrialisation, combined with a strong associational culture and high female employment, catalysed a large working class, who organised to smash hierarchies. Karl Östman captured this egalitarian ambition in his 1923 novel “The Broad Road”:

“The working class must be rescued from serfdom! We must become human beings in the truest sense of the word and live decently in the world, bodily and spiritually. No longer will that privilege belong to a chosen few”.

The Great Levelling!

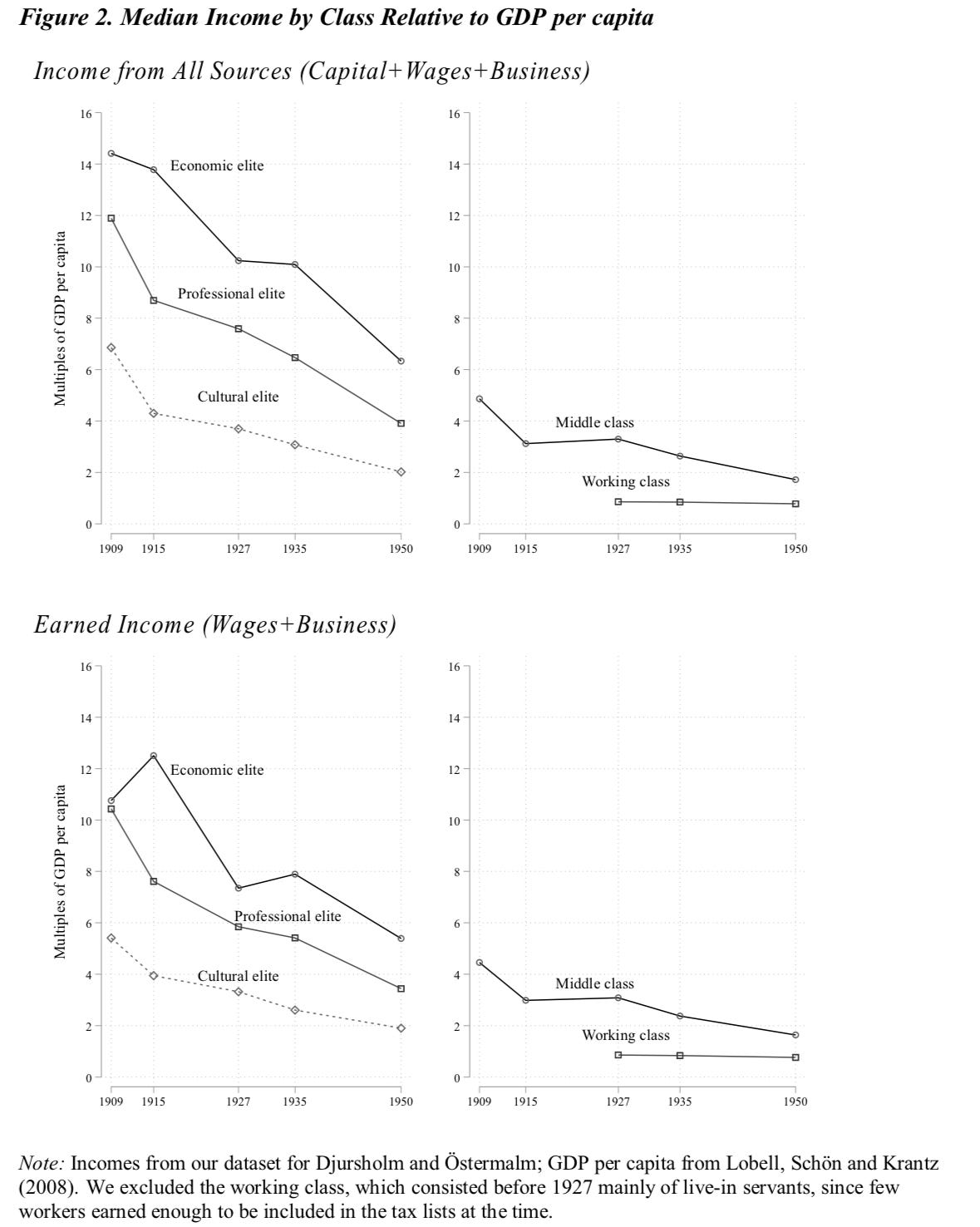

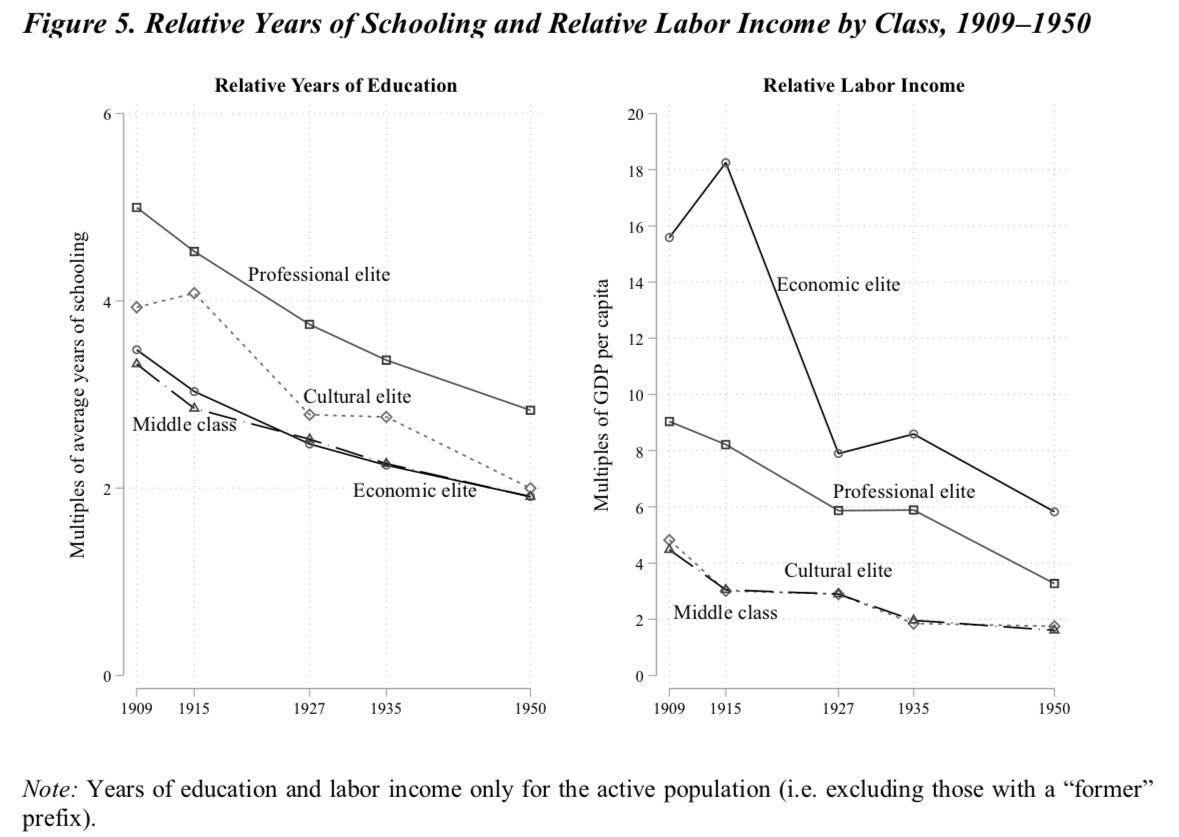

During World War I, Swedish elites earned 15 times the median income. By 1950, it was only six-fold. What happened?

The marvellous Erik Bengtsson and Jakob Molinder propose a two-part explanation: capitalists’ monopsonies were weakened by business competition and state regulation, while working-class mobilisation, collective bargaining agreements, and educational expansion raised the wage floor, reduced the skills premium and closed pay disparities.

From 1915 to 1927, industrial workers’ hourly wages grew by 135%, while their annual incomes surged by 110%!! ✊

Revolutionary Fear and Elite Concessions

But what animated the working class, what equipped them with unswerving zeal, and why did elites so readily concede?

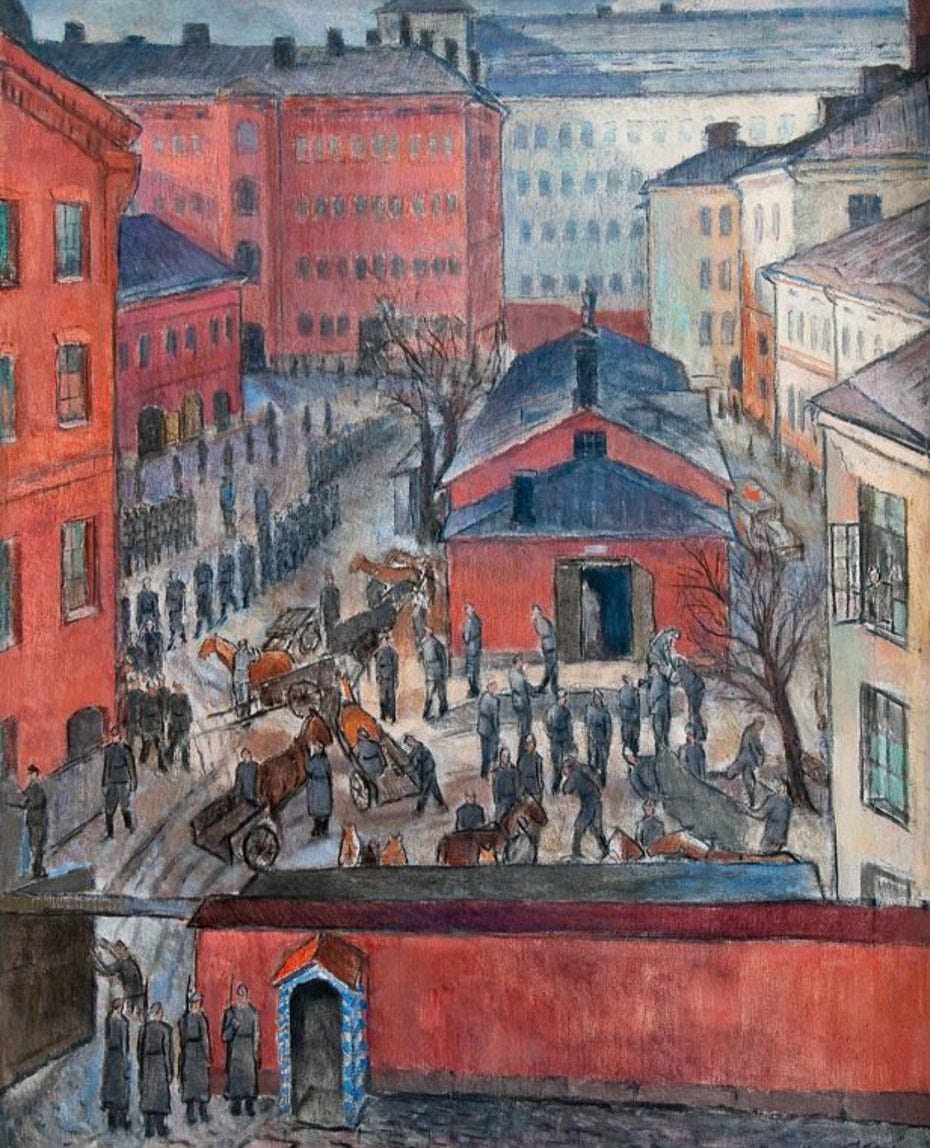

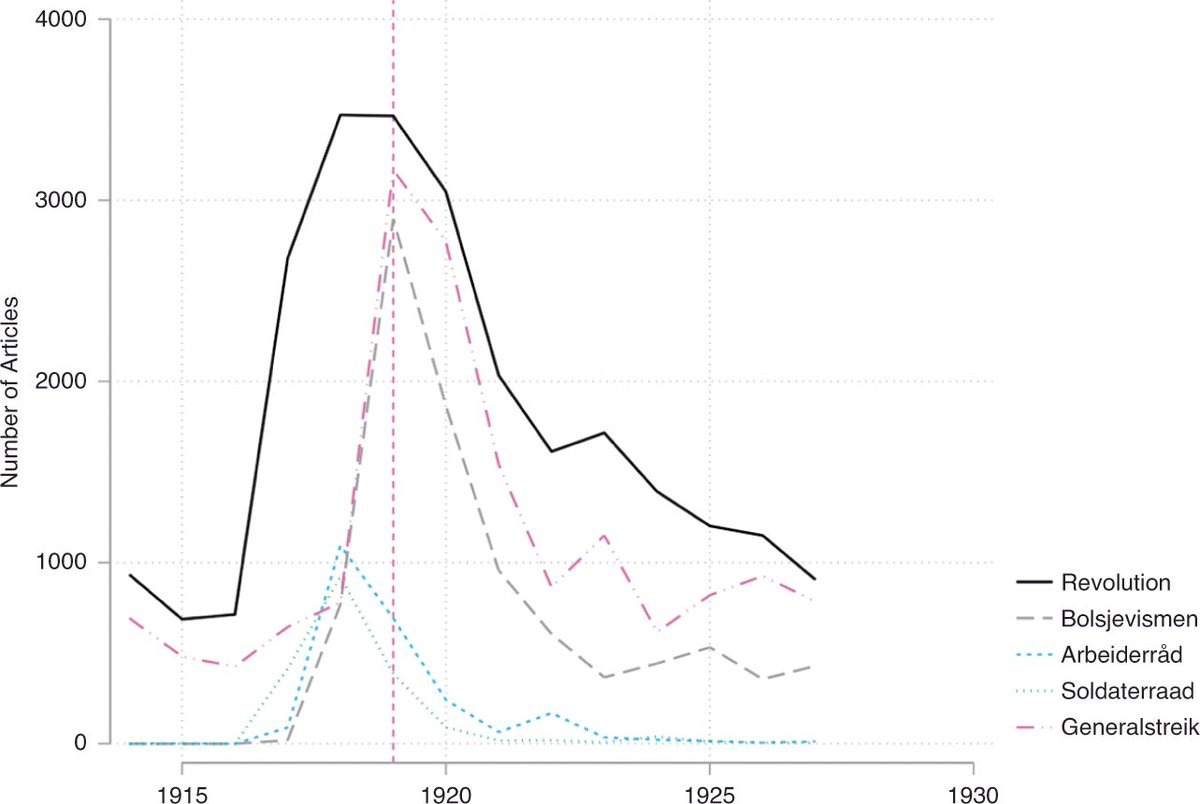

Focusing on Norway, Magnus Rasmussen and Carl Knutsen present a complimentary explanation, arguing that class conflict was exacerbated by leftist excitement about the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

Norwegian Labour leader Tranmæl captured the revolutionary zeitgeist: “One can now clearly see that the fire will spread with a strength such that it cannot be stopped”. Worker and soldier councils organised nationwide, passing resolutions for 8 hour days, and threatening mass strikings. The labour paper Klassekampen called to

“Establish everywhere soldier and worker councils as your body in the struggle for peace!”.

By 1918, the Norwegian Labour Party had fallen under control of revolutionaries who explicitly rejected parliamentary democracy. The party even joined the Communist International (Comintern), which aimed to establish communist organisations ready for European "civil war" and world revolution.

Elites got scared. In 1919 alone, Norwegian newspapers published 3,500 articles discussing the fear of revolution.

The military response was severe: working-class people were excluded from certain divisions, secret police surveilled post and telegrams, and during strikes in 1918, they even sent the battleship Harald Hårfagre.

The Employers' Association (NAF) was so terrified they contacted the Prime Minister directly. Previously confidential board notes, written to be destroyed, reveal their strategic thinking: “Before we would have resisted... All the unrest that exists around the earth at present... We must make sure we can save that which can be saved”.

Norwegian elites then made a series of remarkable concessions. The eight-hour workday, rejected by Liberals and Conservatives in 1915, passed unanimously in 1919. Proportional representation, long opposed by Prime Minister Knudsen in 1911 and 1915, was suddenly embraced in 1919 because, as Conservative leader Halvorsen declared, “the times demand it!” Knudsen himself noted how “Discontent among the socialists has skyrocketed” and pushed his party to accept electoral reform.

Why did Scandinavian elites choose reform not repression?

Why did the elites concede, rather than repress? Certainly, they could have marshalled fascist police violence and stamp out socialism - as in Italy after WWI. In Sicily, Acemoglu and colleagues find that when the Peasant Fasci gained support demanding higher wages and redistribution, landowners marshalled the coercive capacities of the Mafia. Kurt Weyland similarly argues that the Cuban Revolution inspired leftist insurrections across Latin America, which terrified the middle classes who supported authoritarianism.

What explains these divergent responses: concessions versus crackdowns?

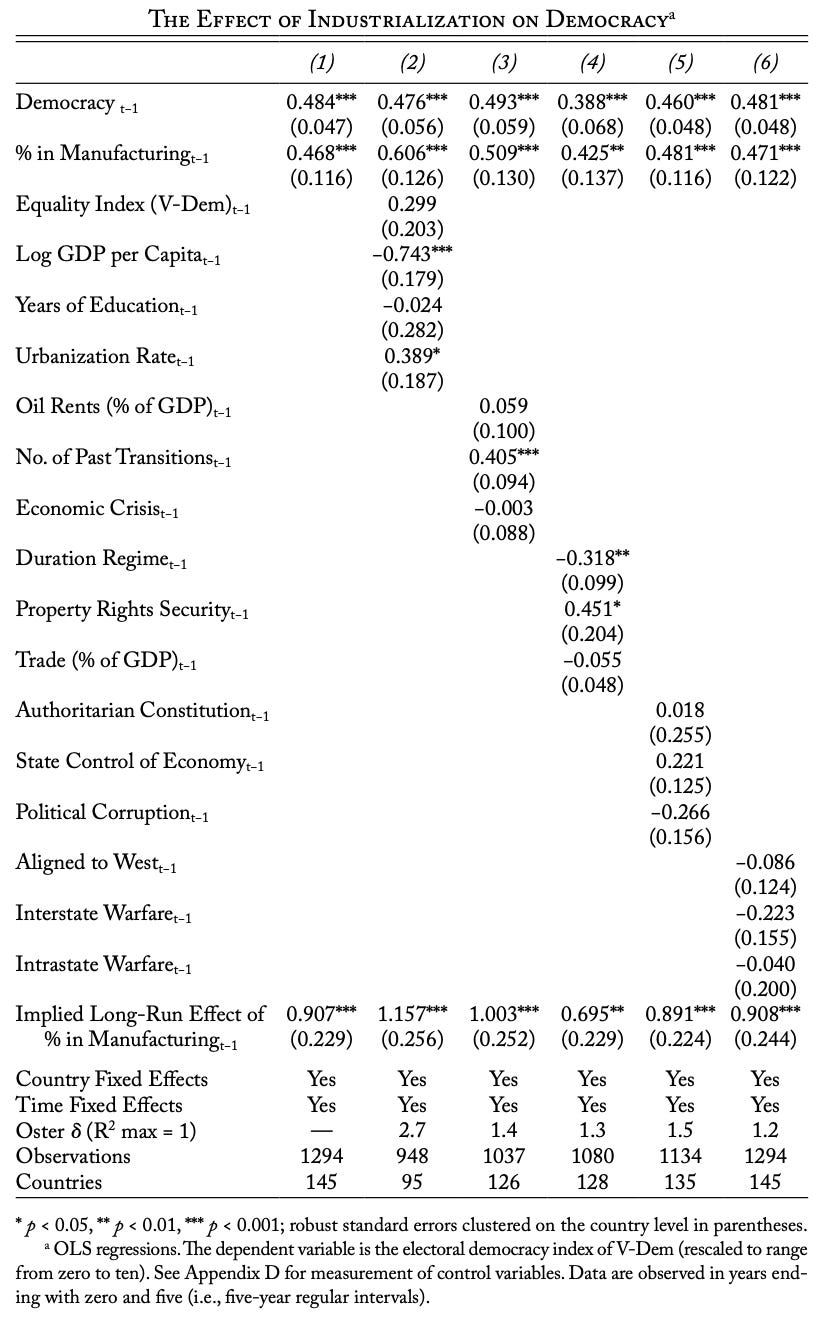

Here’s my hypothesis (drawing on Sam Van Noort): Scandinavia achieved a higher share of workers employed in manufacturing! By 1921, 30% of Swedish workers were in manufacturing. Scandinavian labour movements were thus increasingly organised, united and networked, with deep social ties built through factory floor cohesion. Together with myriad popular movements, this strengthened class consciousness and collective resistance. Of course, this built on a growing culture of popular movements.

By contrast, as late as 1947, only 23% of Italians were employed in manufacturing, and their total level of employment was much lower, since many women remained at home. Large-scale organisational capacities were thus far more hobbled.

Size matters, especially when it comes to the working class. Without a rural surplus, factory owners struggle to break strikes. If a large share of the population are united workers, they could pose a serious threat - both to capital and powerful elites.

Scandinavia’s Egalitarian Legislation

This same associational culture, combined with women writers’ visions of equality and autonomy, led to marriage reforms. The Norwegian Women’s Association (1884), pushed for Norway’s 1918 Marriage Act, granting equal economic and legal rights. In Sweden, the Fredrika Bremer Association and Social Democratic MP Carl Lindh supported the 1921 Act. The 1930s saw further radical changes: strengthening the position of illegitimate children and liberalising laws on homosexuality and abortion. Denmark’s 1925 Act, backed by the Danish Women’s Society and Social Democrats, similarly transformed family law.

By contrast, West German women couldn’t even enter the labour market without their husband’s permission until the 1970s-80s.

Social Democrats in Power

Sweden’s Social Democrats cast a radical new vision - of equality and cooperation, supported by the state - as encapsulated in Per Albin Hansson’s speech of 1928:

“In the good home equality, consideration, co-operation and helpfulness prevail. Applied to the great people’s and citizen’s home this would mean the breaking down of all the social and economic barriers that now divide citizens into the privileged and the unfortunate, into rulers and subjects, into rich and poor, the glutted and the destitute, the plunderers and the plundered”.

While the Social Democrats were certainly radical, they strategically portrayed this as a continuation of Sweden’s cherished identity, positioning themselves as heirs to the free-holding peasants who had “brazenly marched with Engelbrekt and supported Gustav Vasa in his fight for independence from Denmark”.

With historical legitimacy, the Social Democrats rolled out ambitious reforms: improved state pensions (1935), maternity payments (1937), and two weeks’ annual vacation (1938). This heralded a growing acceptance of the state’s overarching responsibility for every citizen’s well-being.

The Myrdals (a married couple of reformists) articulated a radical vision of state responsibility towards children:

“The family's 'right' to let children live in squalor, to neglect their diet and upbringing, to bar them from making a rational choice of profession, and to deny them an appropriate education cannot remain as unlimited as it is currently”.

But they added a crucial caveat:

How did the Social Democrats achieve this vision of equality?

During the 1930s Great Depression, exporting firms saw a large fall in foreign demand, and workers experienced large pay cuts in order to stem the decline in employment. Non-tradable sectors were not directly affected by global fluctuations, but these unions were nonetheless persuaded to take wage cuts so as to prevent high input prices for exporting industries. Employers, firms and government centralised authority and imposed generalised wage moderation.

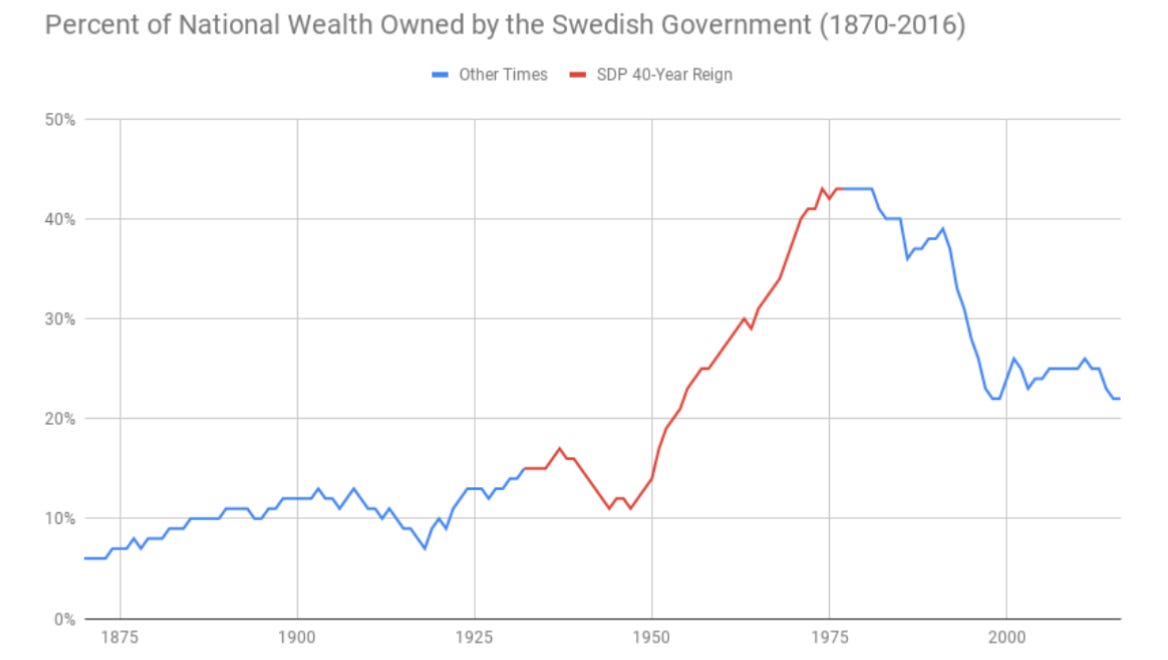

Progressive taxation was a cornerstone of Scandinavia’s egalitarian model, funding robust public services and curbing wealth concentration. From the 1930s, Sweden’s marginal tax rates surged, doubling by 1950 and peaking in the 1970s, preventing the top 1% from rebuilding their fortunes. By 1977, the state owned 43% of national wealth, ensuring resources for public goods that sustained equality.

Sexist Bullying

Notwithstanding all these calls for equality, Scandinavia was still patriarchal. For example, Swedish artists Eva Bagge and Esther Kjerner did not host solo shows, until a dealer arranged this for them in the 1940s. Why hadn’t they done so before?

“If you love your work, you are afraid that scathing criticism will spoil your zeal”, explained Eva Bagge.

Sexism created a silencing effect, pushing women into the shadows, and preventing wider recognition of equal talents. So how did this change?

High Female Education and Share of White-Collar Jobs

In secondary education, Sweden has also seen strong gender parity. Molinder suggests this was encouraged through high returns to white-colour jobs in services. For example,

“if a woman changed her occupation from maid to telephone worker - a typical job available for a young woman in Stockholm at this time - her income roughly doubled”.

Culturally too, women were eager! As 78 year old Vera recalled,

“We were farmers until the 30s, my mother did everything in the barn, taking care of cows and milking, while my father worked in the forest, for timber. Then people went to cities, and women said “I did not come to the city to be a housewife!”

The Feminist Revolution

“Motherhood is history's most exploited feeling”, observed Swedish feminist Eva Moberg. To question this principle risked being seen as "asocial, unnatural, unfeminine, inhuman”.

Even then, in 1961, Swedish women were still supposed to be mothers, while any dissent was vilified. Her powerful essay - “Women on Parole” - was published in the Fredrika Bremer Association's magazine Herta, and then became foundational to Swedish feminism, generating intense debate. Continually, she attacked the deeply-rooted notion that women must subordinate their interests to children’s needs.

“True equality of the sexes requires that women become as economically and socially independent of men as men are of women”, argued Moberg.

Europe and North America’s feminist revolution greatly benefitted from several parallel currents. The 1960s economic boom generated urgent demand for skilled labour. Women were seen as an ‘unexploited labor resource’, which government, trade unions, and businesses were eager to harness. At university, feminists increasingly organised for equality. In Sweden, the Social Democratic Women’s Association argued that for each person to be truly free, they should have their own job:

“A fundamental condition for realising these goals is that everyone has gainful employment. Earning a living is a precondition for individuals to develop an active and independent personality. Additionally, doing paid work oneself is a condition for being economically independent of other people. This requirement is extraordinarily important, particularly for women”

They laid out four fundamental demands:

All adults should have opportunity for independent development

Society should be neutral toward different domestic arrangements

Children's development should be independent of parents' economic circumstances

Individual taxation became a crucial battleground - as “a demand for women's economic independence”. The Association wanted to “proceed on the assumption that adult family members should live economically independent lives… Marriage should naturally continue as a form of shared living”. Further, true community “will best be developed if it is based on economic independence”. Parliament introduced individual taxation, and married women’s labour force participation continued to rise. (Caution: this reform was not necessarily a cause, but rather a consequence, of rising female employment.)

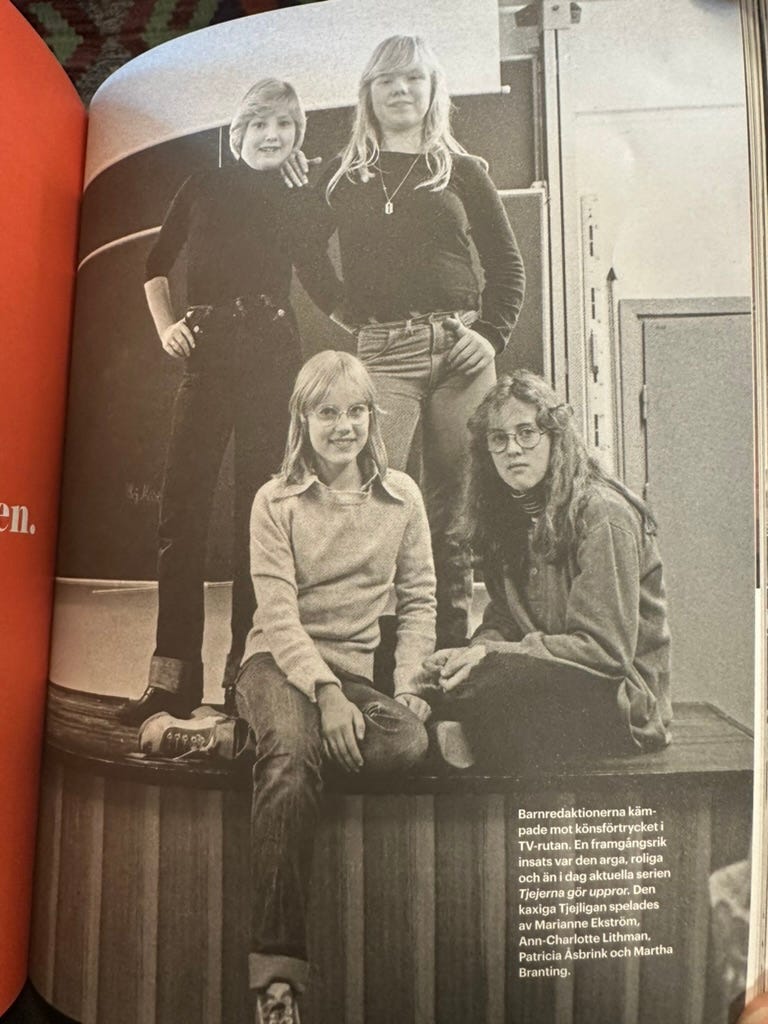

Egalitarian TV

One evening in Lund (Sweden), an elderly man approached me on the tram. Having previously attended my talk, he wanted to make a further contribution.

“When I was a child, there were lots of television shows on solidarity and equality. Can I bring you a book on this for tomorrow?”

Obviously, I was thrilled! Together, he guided me through the entire book, generously detailing every show, including a young naked girl learning about reproduction by meeting a naked pregnant women.

Herein lies a core part of ideological persuasion. Until 1987-90, Nordic countries had public service broadcasting monopolies (Sveriges Television in Sweden, NRK in Norway, and DR in Denmark). State power could thus be marshalled for ideological persuasion, with entire families watching shows that celebrated equality and independence.

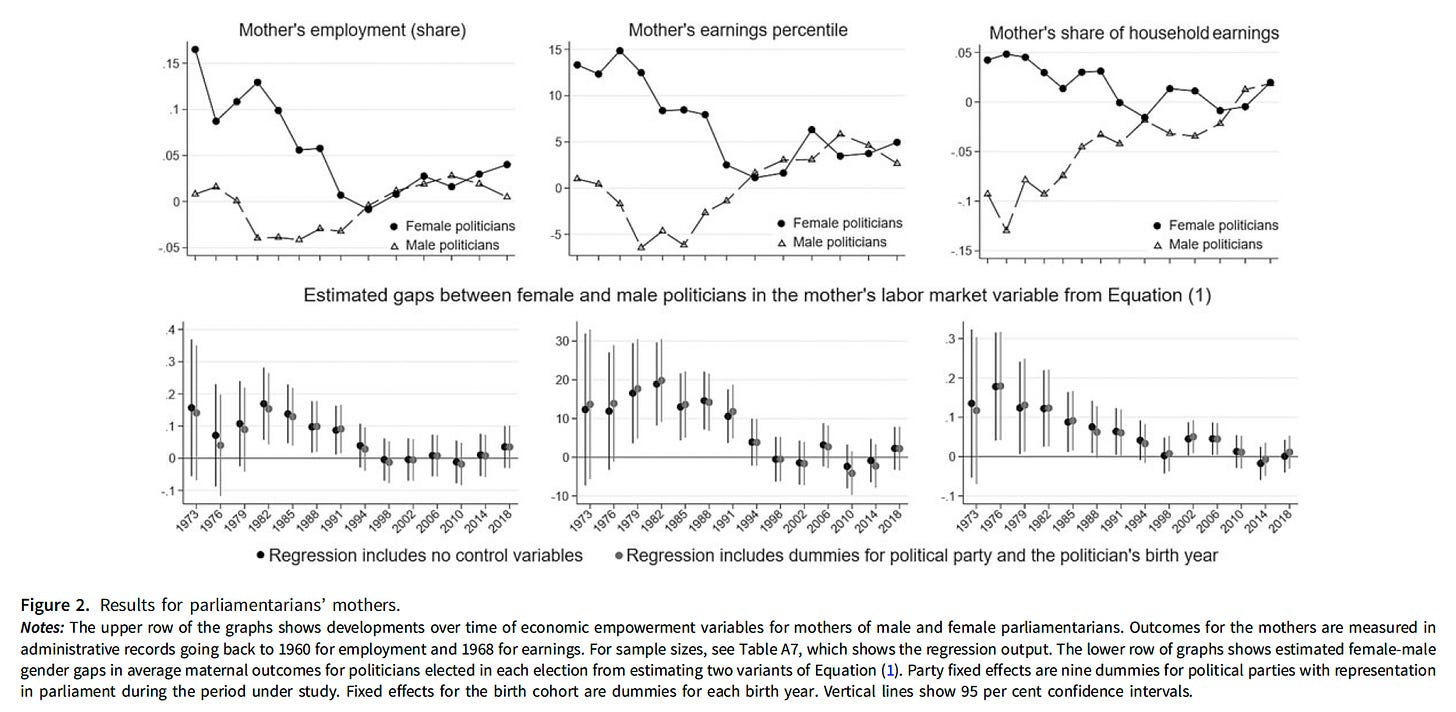

How has women’s employment impacted politics?

As Swedish women seized high-earning jobs, they inspired their daughters to aim big. Frödin Gruneau and Rickne (2024) find that that female parliamentarians in the 1970s and ‘80s often had economically empowered mothers, potentially boosting their confidence to break into Sweden’s male-dominated politics.

Public Childcare

The 1950s and ‘60s heralded the Golden Age of the welfare state, with the introduction of universal social security and health care!

Sweden’s Social Democratic Women's Association further argued that society should take primary responsibility for children’s social, intellectual, and material development. Radicals argued that the home was actually inferior, devoid of stimulation, and that early years care should instead be provided by society.

Over the 1960s and ‘70s, governments introduced maternity leave and daycare. In Sweden, pre-school places dramatically expanded - from 11,000 in 1962 to 338,000 thirty years later. In the 1990s, daycare became universally accessible.

Cultural change was incremental - in 1974, only 2.4% of Swedish fathers took parental leave. Men were reluctant to undertake ‘feminine’ roles, women were unwilling to give up precious time, and it was often economically costly, since it didn’t cover 100% of the salary. When Norway introduced ‘daddy quotas’ in 1993, the share of fathers taking leave rose from 3% to over 30%.

What’s Scandinavia’s Feminist Secret

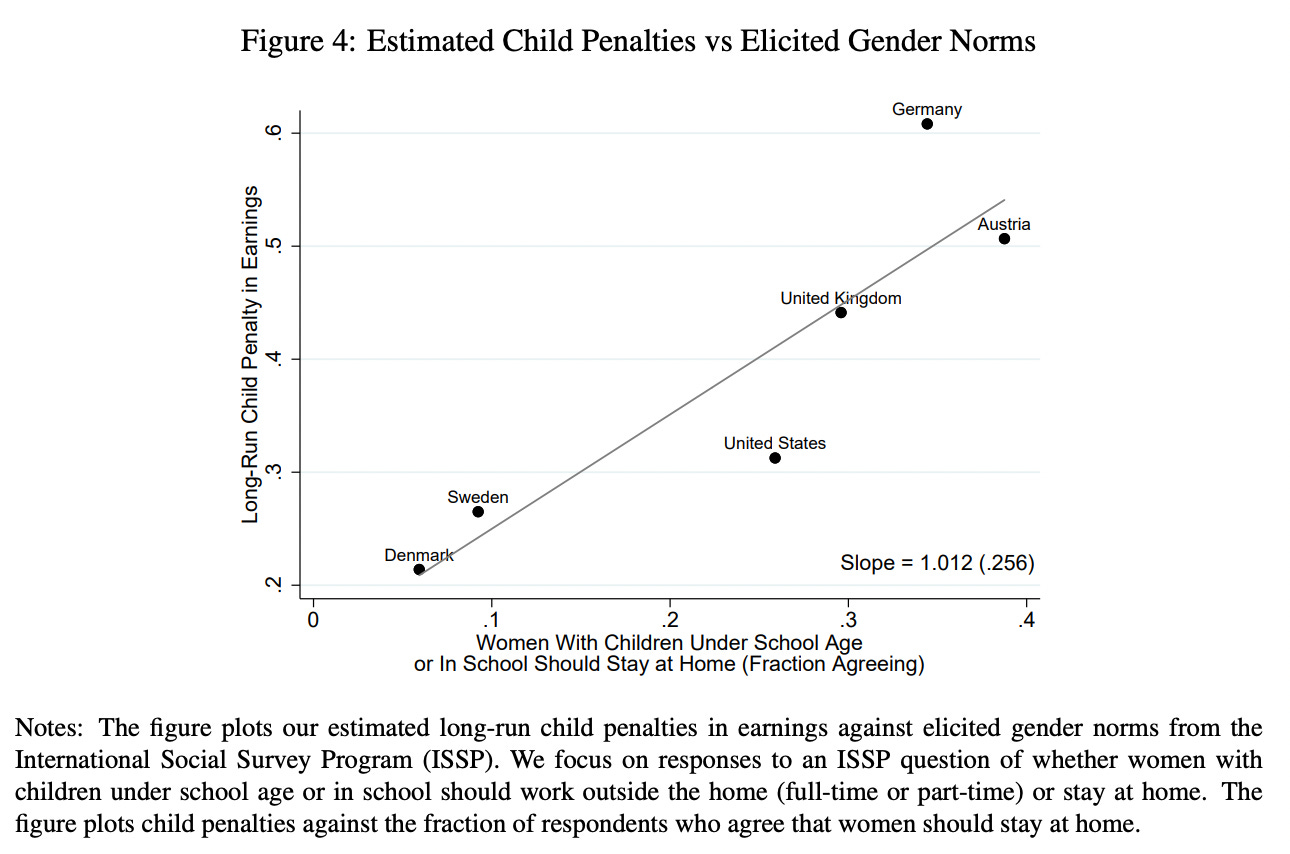

Does publicly provided daycare account for the high employment rates of Scandinavian women, even post-childbirth? Have these policies fostered broad support for working mothers?

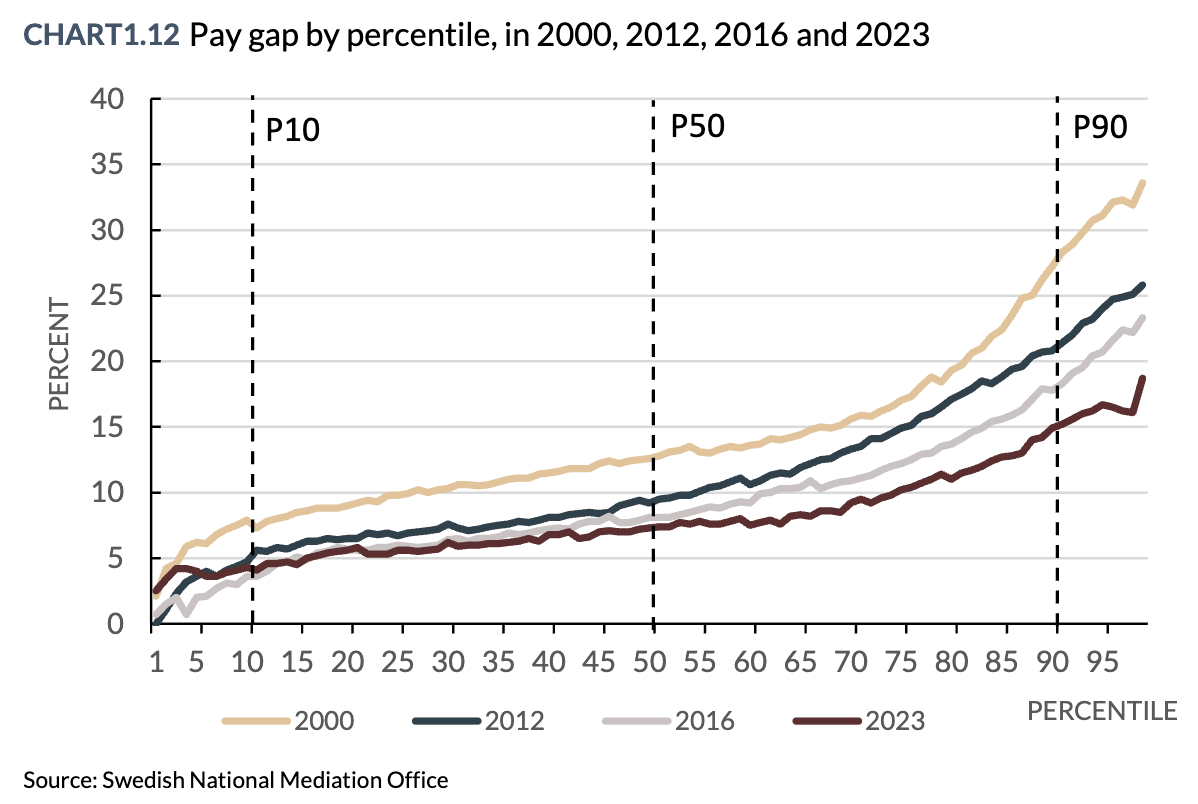

A compelling study by Mogstad, Salvanes, and Torsvik highlights a potentially more important facet of Scandinavia: significant wage compression. Although women often occupy lower-paying roles, the gender pay gap remains minimal because wages across the board are relatively similar.

What Explains the Nordics’ Wage Compression?

Mogstad and colleagues calculate the coefficient of variation and the variance of log hourly wages. Nordic countries are much more equal than the UK and the US. In fact, the variance of log hourly wages is THREE TIMES lower in the Nordics than the US. The 90th percentile in the hourly wage distribution is also five times lower than the US.

The gender gap in hours worked is lower in the Nordics. Further, the gender gap in hourly wages is 30% lower in the Nordics compared to the US.

Mogstad, Salvanes and Torsvik consider three distinct hypotheses:

Children’s health and education investments lead to a compression of skills and productivity, thereby equalising pay;

Work-complementary services (such as child and elderly care) enable women to redouble their commitment to the labour market;

Centralised and coordinated wage bargaining promote income equality.

While Nordics are highly skilled, with little variation in skills, this does not seem to explain the low dispersion in wages. They find that,

“One year of additional schooling is associated with around 3 to 5% increases in wages in the Nordic countries, while the education premium is at least twice as high in the U.S”.

Wage equality stems not from similar talents, but socially constructed rewards.

Might public services that complement work help explain pay parity? While parental leave is certainly generous (49–56 weeks at 70–100% wage replacement), there’s little evidence that it has actually changed women’s labour market outcomes. So what about daycare? Again, while parents may appreciate 95% coverage for ages 2–5, demonstrated effects on maternal employment and earnings actually seem rather modest. It may only substitute for private arrangements.

Now what about institutions?

Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden all have high female participation in unions, high labour union density, and high collective bargaining coverage. Their distinctive two-tier collective bargaining system, comprises sectoral bargaining of wage floors plus local bargaining within each firm. Wage-setting is thus coordinated, within and across industries.

This is the secret sauce of wage compression. It has major implications for gender, for even if low-paid sectors are disproportionately female, their relative share of labour income is actually high! Thanks to associations!!

How does wage compression affect culture?

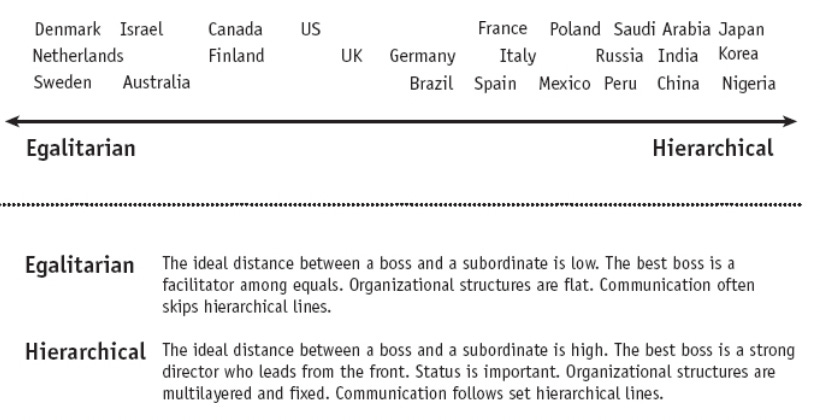

“A boss can’t tell you what to do”, explained Hanson, as we chatted over dinner with his friends (all of whom were members of choir associations, dance association, and the tenant association). He continued, “Swedish firms are extremely egalitarian, and consensus-orientated”.

Over two months of qualitative research, interviewing companies and non-governmental organisations, I noted that Scandinavian bosses typically act like everyone else. Forget corner-offices, they’re hot-desking. No one is special. ‘Leaders’ are not due unique perks, privileges or power. Queuing by the roadside, they board the bus like commoners.

Erin Meyer presents a similar cross-cultural comparison, drawing on interviews with international executives. Jepsen (a Danish manager) explained,

“In Denmark, it is understood that the managing director is one of the guys, just two small steps up from the janitor... Danes call everyone by their first name and I wouldn’t feel comfortable being called anything but Ulrich. In my staff meetings, the voices of the interns and administrative assistants count as much as mine or any of the directors. This is quite common in Denmark.

Although a lot of Danes would like to change this, we have been bathed since childhood in extreme egalitarian principles: Do not think you are better than others. Do not think you are smarter than others. Do not think you are more important than others. Do not think you are someone special. These and the other Jante rules are a very deep part of the way we live and the way we prefer to be managed” (quoted in Meyer 2014).

Meyer suggests that egalitarianism may be an ancient value, but my historical analysis implies it has only emerged due to strong associations and media persuasion.

Here is my novel hypothesis: if everyone is respected, it is much more permissible for (low status) women to become politicians, preachers and bosses. What’s there to envy? The prestige gap is meagre.

By contrast, in hierarchical institutions, where status gaps loom large, it would be enormously unsettling for a (low status) woman to command prestige. If men must always bow and let her first speak first, it may grate their egos. Even for men who are perfectly supportive of female employment or gender equality in abstract, it might still be uncomfortable to literally kow-tow. The larger the hierarchy, the more distressing it may be to see a woman soar.

How did Scandinavia become the most gender equal region in the world?

Weak ideals of seclusion yielded high female employment, while a culture of associations and industrialisation enabled the working class to extract concessions. Under the Social Democrats, wages were compressed, while media championed egalitarianism. Thus even though women cluster in more low-paid jobs, their wages are still relatively high. Furthermore, if everyone is equal, no one begrudges women at the top. Thus, over recent decades, occupational segregation has declined, more women are becoming managers, and the pay gap is declining at the top!

If the secrets to Scandinavia’s success are an absence of modesty, coordinated bargaining, and wage compression, the big question is how to preserve these socio-economic institutions amid a slowdown in labour productivity and demographic change. For all this talk of utopia, Sweden has failed to support migrant women’s integration and economic activity.

That is surely the biggest challenge for 21st century feminists.

Thanks Alice, hope you were in Stockholm during the right half of the year. Another factors that might played role are the few people that lived in the vast territories of NO, SE, FI and the climate which is for about one third of the year life threatening

Excellent piece! I think there's another factor worth exploring - proportional voting, which incentivizes compromise and coalition building, and has been linked to higher female representation in governments. I wrote about it here: https://darbysaxbe.substack.com/p/why-hasnt-the-us-elected-a-woman