Why is Scandinavia the Most Gender Equal Place in the World?

Part 1

Status hinges on who commands respect and who is revered as a powerful leader. By these metrics, Scandinavia shines as the most gender equal region in the world. Men and women are seen as equally entitled to jobs, with comparable competence in political and business leadership. Women’s employment, wages, share of management, and parliamentary seats outpace much of the globe.

What forged this rare triumph? Should we credit the Vikings, Luther, or Social Democrats?

For starters, we should recognise that gender equality is an improbable feat. For roughly 300,000 years of human history, women were vulnerable to rape, beatings, and enslavement. Pregnancy, nursing and precarity deepened reliance on male providers, encouraging submission in exchange for care and protection

Europe and North America escaped this trap through a fortunate confluence of factors: Christianity sanctified the nuclear family, the Protestant Reformation elevated marital bonds, the Enlightenment championed free expression of dissent, while robust states enforced laws and provided core services. Technological advances, media connectivity, and economic growth then proved transformative: women gained control over their fertility, pursued careers, built diverse friendships, demonstrated equal competence in socially valued domains, and mobilised for reform.

Yet Scandinavia had two unique latent assets which would prove transformative in the 20th century. Scandinavians never idealised female seclusion and there was a nascent culture of associations. Neither entailed gender equality, but rather they provided the latent assets for egalitarian ideological persuasion and capture of state power.

Part 1 traces Scandinavia’s cultural evolution from the Vikings to Medieval Christianity, Luther, Romanticism, Enlightenment, and 19th century women writers. Part 2 explores working-class mobilisation and key policy reforms under the Social Democrats. Combined, these two essays reveal the secret sauce for gender equality.

Viking-age Scandinavia

Was the Viking Age (800–1050 CE) a bastion of gender equality, with women warriors wielding power? Au contraire. Only 30 Viking Age graves of women with weapons have been identified across present-day Denmark, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden - that’s only 2% of all surviving burials, with only half professionally verified.

Viking Scandinavia was unabashedly patriarchal. Old Norse myths gloried men like Thor and Odin as dominant aggressors. Politically, women were marginalised: they could attend the Alþingi (assembly) but sat “outside of the benches” as observers, barred from acting as jurors or initiating legal proceedings except in rare cases.

Marriages were often arranged, with payments (mundr) made to the groom’s family. Crimes against women were likewise seen as offences against their male relatives, not the women themselves. The Grágás laws decreed that domestic violence was only grounds for immediate divorce if it caused ‘major wounds’, but was otherwise tolerated.

Elites amassed multiple wives and concubines to forge political alliances and satisfy their sexual desires. Some were abducted: the Annals of Ulster details that Viking raiding groups captured women on Etar, Ireland, while Arab traveller Ibn Fad noted that Rus merchants sold women as sex slaves.

Language reflects concubines’ inferiority. The Old Norse words for ‘slave woman’ (ambátt) and ‘concubine’ were used interchangeably, while the term for ‘son of a slave woman’ (þýsun) evolved to mean any child born out of wedlock. The laws of Gulaþing and Frostaþing accorded similar rights to the children of slaves and free concubines. Icelandic laws equated the children of slaves and those born out of wedlock - neither could inherit.

Yet, Viking-era Scandinavia was relatively permissive. Sagas describe married women taking lovers, and even becoming pregnant without punishment. In Iceland, adultery was not grounds for divorce. As Christianity took hold by the 12th century, laws began to shift, fining concubinage and promoting monogamous marriage, signalling a slow cultural transformation:

Christianity & Luther’s Revolution

Christian missionaries spread the word from the 8th and 9th centuries. Conversions were more rapid in Denmark, whereas in sparsely populated and politically fragmented Sweden, pagan strongholds persisted with into the 12th century.

Churches prohibited polygamy and enforced nuclear families. So here’s something that gender scholars are unlikely to admit: rich and powerful men wanted to sow their wild oats and enjoy multiple wives, but their wants were shackled by punitive Christianity.

Another step change occurred in the 1520s, when Gustav Vasa led the Swedish War of Liberation and shrewdly embraced Lutheranism. The Church owned 20% of land, while the state only had 5%. Lutheran doctrine legitimised Vasa’s seizure of church property, solved the debt crisis, and weakened a powerful, oppositional institution. Lutheranism was thereafter institutionalised top-down.

Everyone was expected to read the Bible, tested via annual ‘house interviews’ (husförhör), which also promoted learning of agriculture, law, medicine, and other practical subjects. ‘Sola scriptura’ (scripture alone, rather than deference to clerics) also aided subsequent calls for liberalism - justifying individual freedom of expression.

Northern Europe developed nuclear households, distinct from Mediterranean or Eastern European multi-generational families with strict hierarchies. Scandinavians married later, spending years as wage labourers, fostering what historian Michael Mitterauer called “a period when the individual, the autonomous personality, was developed”.

Weak Cloistering

Scandinavian Christianity retained remarkable permissiveness. Ibn Fadlan, travelling from Baghdad in 922, was shocked to see Scandinavian merchants having sex with enslaved women in public view. In 1432, a Venetian captain shipwrecked on Norway’s Lofoten archipelago noted locals bathed naked together, unashamed.

A hundred years later, Andrew Boorde observed Icelandic priests keeping “concubynes”. 17th century travellers noted, with surprise, that bathhouses were sometimes nude and gender-mixed.

In northern Sweden and Finland, where agricultural productivity was low and class divisions were minimal, unmarried men and women might spend nights together without parental approval (‘nattfrieri’ - night courting). In 1799, Malthus noted that Swedish country girls often had “sweethearts for a considerable time before they marry” - frequently accelerated by pregnancy. Even in the late 19th century, 16% of first births to University of Iceland’s Theology Faculty were illegitimate.

What explains this permissiveness?

Low population density, minimal urbanisation, and sparse monasteries and bishoprics likely weakened the Church’s ideological control. Richard F. Tomasson argues, “The older permissive pattern persisted in those areas where the influence of Christian conceptions of marriage was weakest”. This openness enabled high female labor force participation, but that’s only one part of Scandinavia’s feminist secret…

16th Century Equality, Parish Assemblies & Representation

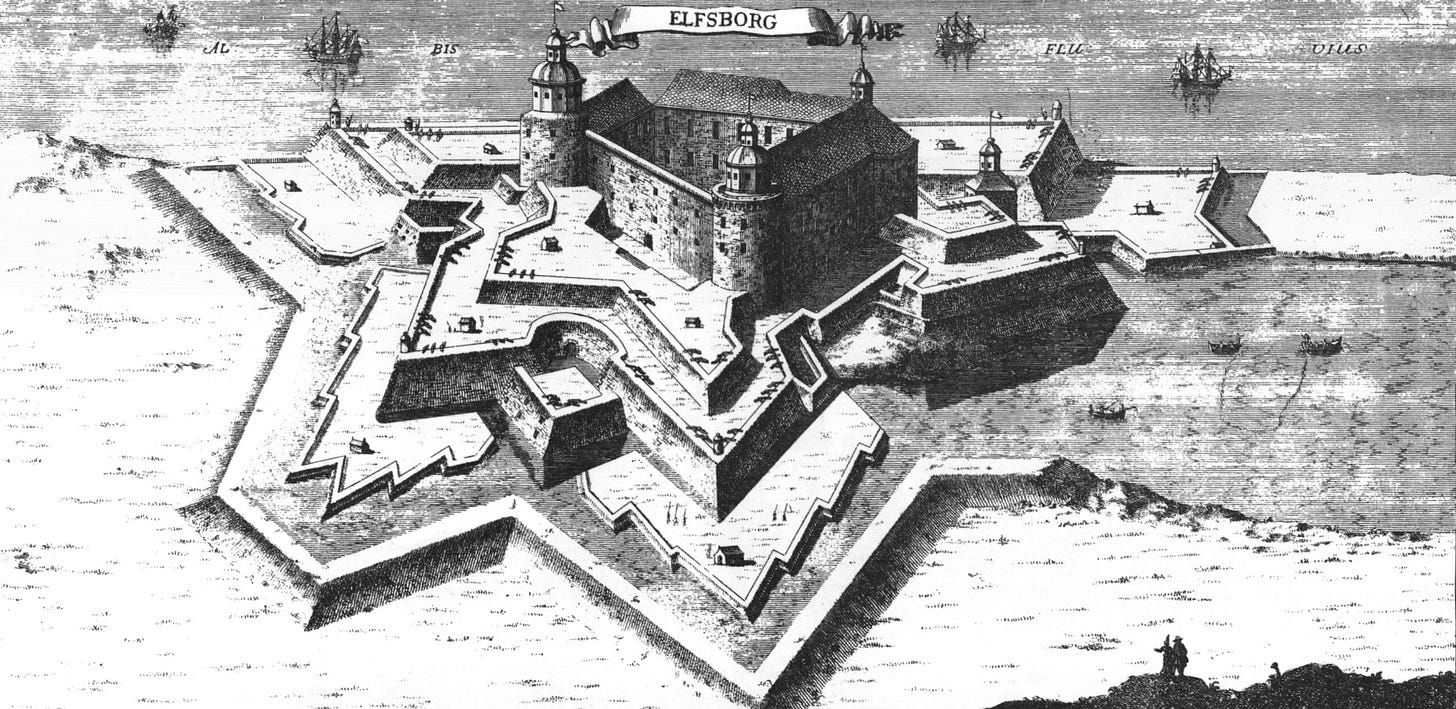

During the Kalmar War (1611–1613), Denmark–Norway captured Sweden’s strategic Älvsborg fortress, controlling Atlantic trade routes. They demanded a staggering ransom - equivalent to 3 years of export earnings!!! Sweden financed this through an innovative tax levied on nearly all individuals over 15, including royalty and nobility, administered through parish meetings and existing bailiff records.

Even without seeing the data, we already get a hint of the distribution. All singles and married couples were obliged to pay tax, proportional to their economic standing. There was a strong effort to appear ‘fair’. If even the nobility were taxed, they evidently lacked the power of evasion.

Andersson and Molinder indeed discover that Sweden’s economy was strikingly egalitarian - far more so than other European countries. In 1613, the top 1% only held 13% of income, while peasants earnt 57% of national income. In Sweden and Finland, the bottom 90% earnt 73% of national income. With a tiny nobility, a clergy diminished by Reformation land seizures, and burghers confined to small towns (just 6% urban), Swedish peasants exercised unusual influence through the sockenstämma (parish council).

Landowning peasants (sockenmän) voted by mantal - land-based tax units - to manage education, church upkeep, poor relief, and military support. Formalised by the 1686 Church Law, these councils organised communal tasks via rotar (districts), fostering dugnad - mutual effort for the common good. Peasants’ economic clout gave them leverage to negotiate with the state, making the sockenstämma a hub of local autonomy and a training ground for associational culture.

Now here’s where Swedish peasants got lucky: their economic and political clout fortuitously coincided with the formation of the four-estate parliament, which uniquely included peasants alongside nobles, clergy, and burghers.

However, Sweden’s inclusive institutions did not prevent a significant rise in inequality. The 17th century saw a rapid expansion of the state bureaucracy, with a growing class of civil and military officials, rewarded with landed estates. By 1700, the nobility held 33% of all land.

Scandinavian Industrialisation & Enlightenment

The 18th and 19th centuries saw a surge in revivalist religious and educational movements, consolidating an associational culture. Pietism’s study groups and Denmark-Norway’s 1741 Conventicle Ordinance, which legitimised such meetings, fostered local cooperation. Grundtvig-inspired folk high schools in Denmark created networks for collaboration.

Technology turbo-charged far greater coordination: railways (1830s–1860s), telegraph systems (1850s), cheaper postal services, and steam-powered printing presses increased connectivity, spreading ideas through newspapers and journals

In cities, intellectual and cultural life flourished with lecture halls, salons, theatre, music, poetry, art, and bookshops. An emergent middle class sought public leisure spaces - traditional coffeehouses evolved into Konditori, modelled on Viennese establishments, which welcomed women.

Scandinavia was still a man’s world

Men dominated parliament, judiciaries, universities, religion, and societies. Women had virtually no rights - they couldn’t vote, own property, or work without a husband’s permission.

Sweden’s 1734 Civil Code rendered unmarried women minors under male guardianship until marriage, when husbands assumed control. In 1795, British feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, traveling across Scandinavia, observed that while young couples enjoyed unusual liberty, marriages could be tyrannical. With wives bearing multiple children and heavily dependent on husbands, exit options were weak, and divorces were rare. Male abuse could persist with impunity.

Norway’s 1814 constitutional assembly excluded women, and they had no representation in the Storting. Women were barred from universities, gaining status only through marriage. Only in 1842 did Norwegian law permit unmarried women to practice crafts! When the Storting considered married women’s property rights in 1884, a male-only council defeated the proposal - prompting backlash from male writers, with Ibsen to compare it to “asking wolves to approve of increased measures of protection for a flock of sheep”. Precisely right! High-status domains were dominated by men, who celebrated other men’s advances, consolidating their supremacy. Pietistic moral texts still valorised women’s roles as wives and mothers, while working class women slogged away for pittance.

While Scandinavia was still a man’s world, ongoing intellectual changes and industrialisation would ultimately enable feminist contestation and ideological persuasion.

Associations & Enlightenment

The 1880s kicked off Norway’s golden age of popular movements (“Assosiationsaanden”). These typically included farmers, fishermen, temperance, small holders, missionary associations, and humanitarianism. Local associations - with elected boards, written constitutions, and formal membership - wielded significant autonomy and coordinated nationally. Activists shared tactics, coordinated campaigns, drafted legislation, and documented legal inequalities.

Enlightenment thinkers like Erik Gustaf Geijer and Carl Jonas Love Almqvist championed progressive visions by pointing to medieval traditions of peasant independence, recrafting Nordic identity to align with individual freedom. Geijer’s political philosophy crystallised around four ideas: the individual (not the family) is society’s basic unit; freedom requires equality and independence; the state’s role is to emancipate individuals; and individual freedom is a state project.

Almqvist’s novel Sara Videbeck (1839) championed female independence, arguing true love required economic independence. Ellen Key further proposed the state assume responsibility for children to liberate women from dependence on men, framing this as consistent with Scandinavia’s historical emphasis on individual autonomy.

Scandinavian Romanticism: Reframing Identity!

After the Napoleonic wars, some writers and artists embraced Nordic sagas - think Ibsen’s early dramas or Asbjørnsen and Moe’s 1841–44 Norske Folkeeventyr. Some intellectuals positioned Scandinavia as exceptionally progressive, drawing on ancient myths and nature - fjords, mountains, forests - as canvases for authentic self-expression. Standouts included Esaias Tegnér’s Frithjof's Saga (1825), Johan Ludvig Runeberg’s Fänrik Ståls sägner, Johan Christian Dahl’s rugged landscapes, and Edvard Grieg’s folk-classical fusion.

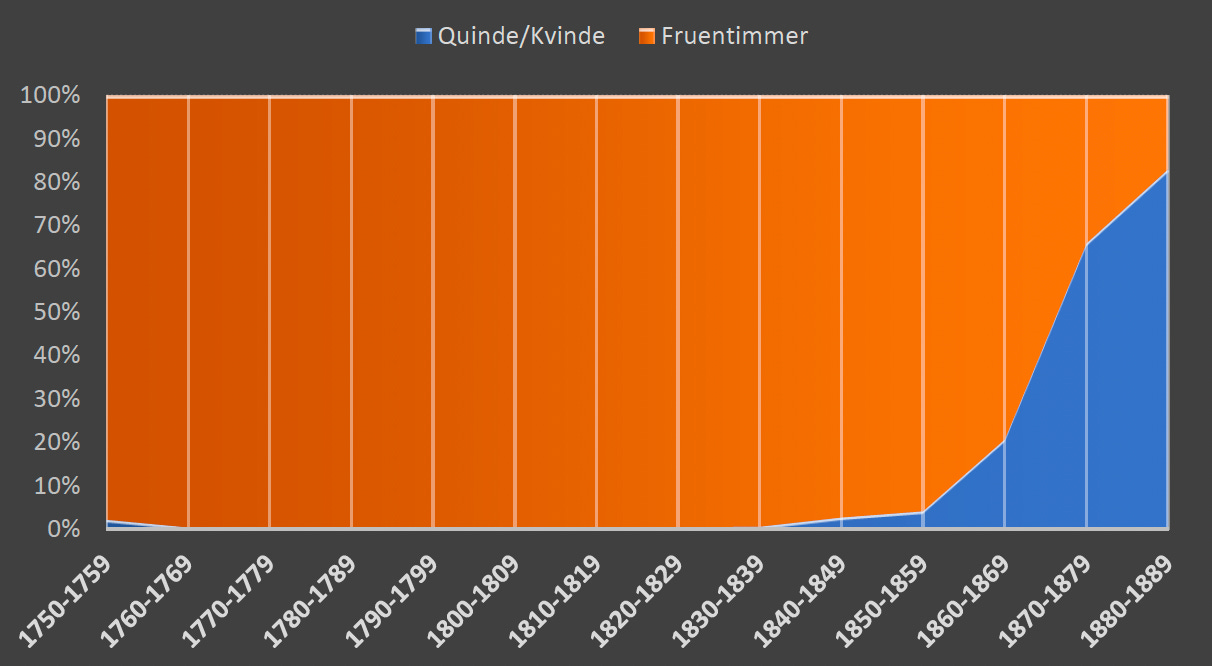

Poets Adam Oehlenschläger, B.S. Ingemann, and N.F.S. Grundtvig deliberately infused “kvinde” with new meanings drawn from Norse mythology, celebrating supranatural valkyries (who choose whether warriors live or die), shield-maidens (warriors), and other strong female characters from the sagas, they expanded the meaning of femininity, even invoking Amazons from Greek mythology. Female warriors became popular figures across Scandinavian plays, novels, and songs.

Grundtvig, a Lutheran priest and cultural leader, wove Norse mythology, Lutheran theology, and nationalist sentiment to champion strong Nordic women created as equals. His 1809 call urged Danish women to awaken: “You are a woman, but not the southern soft, weak woman. Remember! You are meant to be a shield maiden, born to fight and love.”

When Mathilde Fibiger published her controversial feminist novel “Clara Raphael” in 1851, Grundtvig defended her with a poem casting her heroine as a shield-maiden, championing female emancipation as in accordance with nationalism. Oehlenschläger’s 1819 Danish national anthem gave equal centrality to “noble women, beautiful maidens, and men and brisk swains.” Queen Margaret I, who united Denmark, Norway, and Sweden under the Kalmar Union, became a symbol of female leadership, emblazoned on the Danish Women’s Society journal in the 1870s. Danish suffragist Pauline Worm described herself as “a bit of a poet, even more so a thinker but mostly a Valkyrie.”

Craftily, these writers presented female strength as authentically Scandinavian - part of their cherished identity and perfectly permissible. Romanticism also reflected a weakening of ecclesiastical control and the permissibility of embracing alternative identities.

Women Writers: Voices of Defiance

With rising wealth, families increasingly educated their daughters (en par with sons), generating both the supply and demand for women writers, who engaged with wider intellectual currents. Salons and literary academies emerged - sometimes led by women like Malla Silfverstolpe’s, Fredrika Limnell’s, and Calla Curman’s, alongside literary academies hosted by Nordenflycht and Lenngren - all predicated on the absence of female seclusion

In the 19th century, women writers leveraged print culture and circulating libraries to challenge patriarchal prestige. Penning engaging novels and persuasive essays, female authors encouraged middle-class discussions and inspired reform.

Fredrika Bremer, born in 1801, was taught that men men and women are equals, created in the image of God. Travelling across the US and Europe, she critiqued Lutheran ideals of widely submission, and celebrated single women - calling herself ‘betrothed to my pen’. In one letter she wrote,

“I would like to become an author to whose works everyone who is sad, depressed, and troubled (and especially everyone of my own sex who is suffering) could go, assured of finding in them a word of redress, of comfort or encouragement”.

In another, she wrote,

“For no one can deny that love, life, enthusiasm are burning most warmly on earth in the hearts of women. If this holy flame were to be cultivated properly [i.e. if women could go to university], if it were directed towards burning for great and noble goals - what an impulse would not be given to the entire life of society! and how beneficial and noble would not be the activities as women as friends, as wives and mothers, or simply and grandly as - women citizens!”

In Brothers and Sisters (Syskonlif, 1848), the character Gerda seeks purpose beyond domesticity: “I know that there is a life beyond that of housekeeping, even for women, a life, an activity for thought, as noble, as beneficial as the other.” Her book “Hertha” sparked public and parliamentary discussions on women’s rights. It is also the title of the world’s oldest feminist magazine. In 1858, single women over 25 gained the right to acquire legal independence in 1858.

“I would like to become an author to whose works everyone who is sad, depressed, and troubled (and especially everyone of my own sex who is suffering) could go, assured of finding in them a word of redress, of comfort or encouragement”.

Norwegian novelist Camilla Collett (1813–1895) wrote: “I grew up under the threefold pressure of a crushing loneliness, individuals of gigantic strength in my nearest family… and a harsh law of femininity.” She initially saw her brother as a genius but realised nurture, not nature, shaped their paths: “Take two similar shoots from a thriving forest plant… one shoots up strong and fruitfully whilst the other droops.”

Her District Governor’s Daughters was “the long-repressed scream of my life,” portraying “the destinies in store for daughters of the educated classes, especially in… rural areas… nothing other than tragedies.” Her open letter protested sexual double standards: “It doesn’t seem to upset [society’s] logic… that moral inequality, full freedom for him and strict chastity for her, is based on a physical impossibility… it is the victims who are struck down, the despoilers who go free.” Traveling through Italy, Germany, and France, Collett criticised European authors’ passive female characters, introducing Norwegians to George Sand, Legouvé, Balzac, and John Stuart Mill. She likened Europe to a chariot race where England led and Norway lagged.

Amalie Skram (1846–1905) highlighted men’s impunity for violence, responding to critics: “So people suffer and are upset by reading my book—well let them! When I was in Christiania recently there were men who were raping children… I cannot overlook all this.” Swedish novelist Selma Lagerlöf complained to Sophie Elkan about the male-dominated literary establishment. Translations of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and Mill’s On the Subjection of Women (1869) energised debates, questioning church and patriarchal authority.

Over the late 19th century, Norwegian young women increasingly rejected ideas that stepping into the public sphere would hurt their femininity, or that husbands were to be revered as superior. Instead, they sought loving husbands, who would listen and treat their wives as equals. Simultaneously, many sought greater knowledge and public influence. Drawing on John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor, as well as British suffragism and French feminism, many sought equal rights.

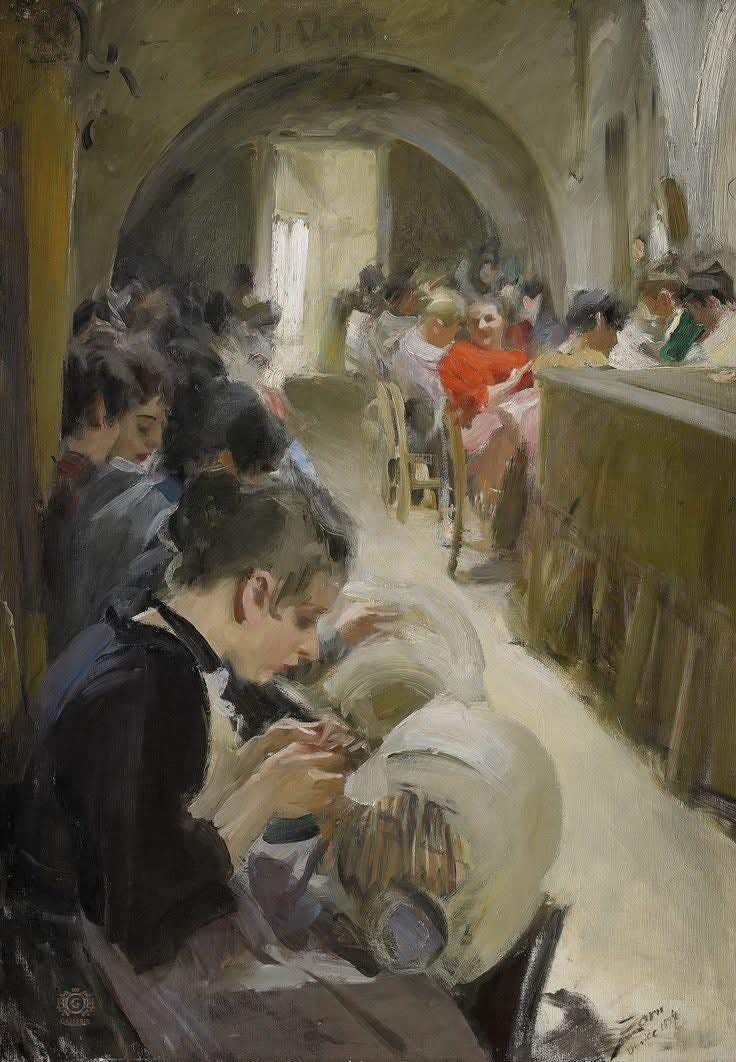

Women in Art

Scandinavia’s esteemed institutions elevated their prestige by excluding women. That said, a weak cult of modesty meant that eager and ambitious women made in roads into public life, iteratively demonstrating their equal competence. To illustrate these transgressions and contestations, let’s turn to a patriarchal club: the art world!

In 1847, Amalia Lindegren was admitted to the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts as an ‘extra student’. She was not allowed to attend life classes. But after exhibiting, she was made an associate member in 1850, the first woman in Europe awarded a state travel scholarship to study in Paris and Munich. Legally a minor at 36, she required a chaperone. Individual freedom and state support (quintessentially Swedish) enabled her to learn at these prestigious cities, where she adopted ‘genre painting’ of everyday life.

Her royal portraits and domestic scenes, reprinted as lithographs, earned praise: “She paints just like a man”, observed one of Sweden’s leading newspapers. Broad recognition of her competence paved the way for the Academy permitting women (1963). The Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm was also the first in Europe to welcome students to draw nude life models, in 1864.

Female Friendships

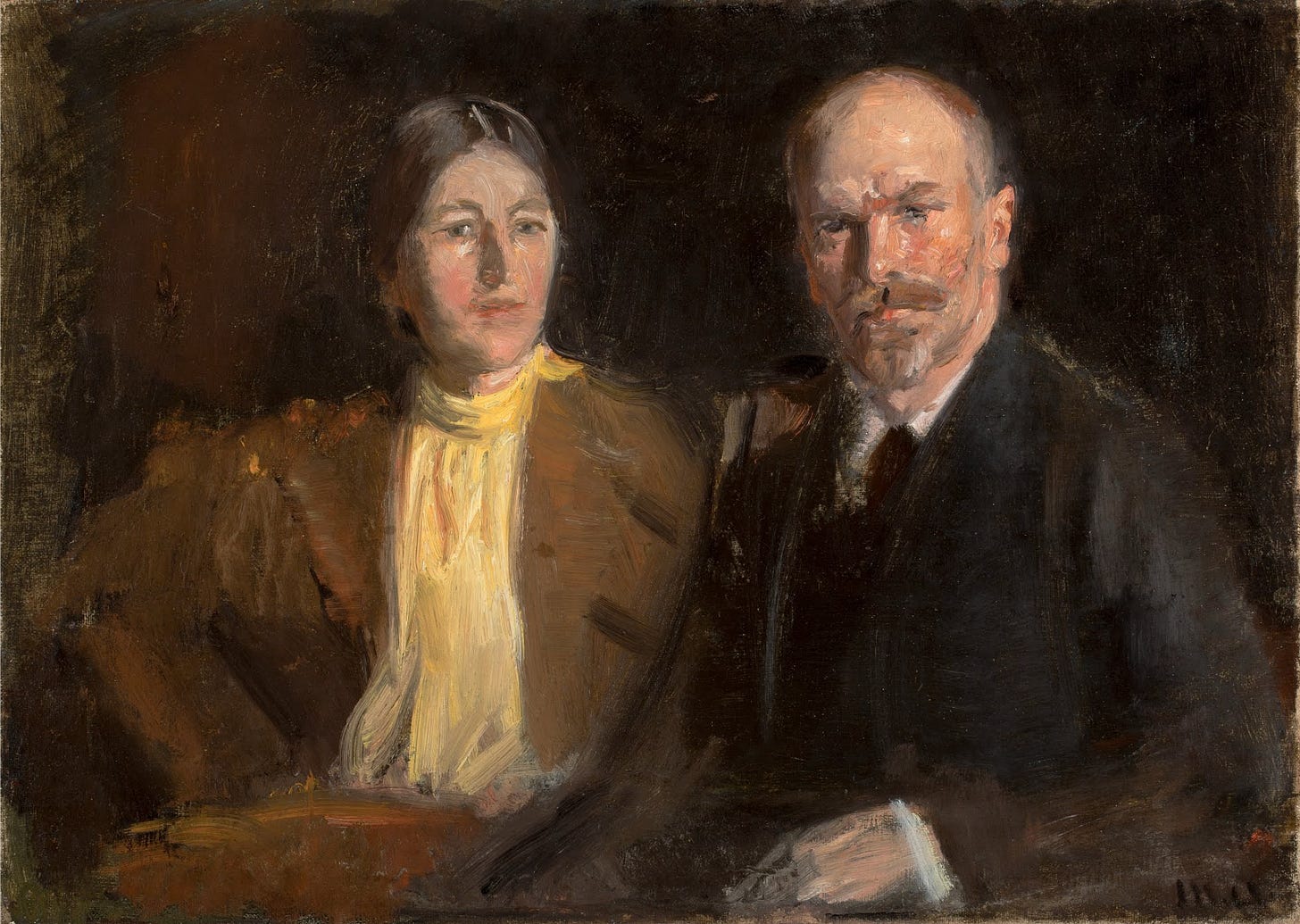

Danish Bertha Wegman and Swedish Jeanna Bauck met in Berlin, where they trained as artists, then subsequently moved to Paris. As close companions, they painted many paintings of each other. Below, you see Jeanna’s painting of Bertha - challenging the idea of art being exclusively male. Indeed, she founded a school for female artists. Second is a more informal painting of Bertha.

Together, they put women artists into the frame.

Julia Beck was a leading artist in the Swedish colony in Paris. Weak policing of women’s bodies meant their could seize the best educational opportunities, travel afar, mix and mingle, demonstrate their competence and gain status! Permissibility also meant that people could mix and mingle, and share ideas as friends.

Almost a century before the U.S. TV show, Hanna Hirsch-Pauli painted this celebration of “Friends”. Ellen Key (feminist philosopher and educationalist) sits centre-stage, reading to her friends in Södermalm, Stockholm. The social circle includes the artist’s sister, actresses, artists, publishers, educationalists and writers. Hanna trained in Stockholm and Paris, frequently exhibiting in Nordic exhibitions, as well as Paris and Chicago. Ellen Key (1849-1926) was a key thinker - championing individualism, women’s education, paid employment. And through financial independence, women would marry for love, also enjoying sexual fulfilment.

Romantic love!

Progress towards gender equality is not just about women having the freedom and permissibility of self-expression, but also male support and devotion. Romantic love is a hugely important, but under-rated driver of gender equality. Men who cherish their wives prioritise her wants and welfare. The two portraits below celebrate marital intimacy and devotion, with painters showing themselves with their wives.

1900s Scandinavia was Still Unequal

Scandinavia shared much in common with Europe and the US: breaking free from crippling poverty and conservatism, it underwent industrialisation and intellectual reform. Yet, neither were panaceas for equality.

Privileged farmers, merchants, industrialists, and professionals amassed wealth and political power. By the 1890s, Swedish farmer MPs were seven to eight times wealthier than their constituents, with substantial investments in banks, railroads and industry. Farmer MPs allied with conservative landowners to maintain one of Europe’s most restrictive voting systems - in 1890, only 21% of adult men could vote, compared to 73% in Denmark. The Country Party, uniting wealthy farmers with estate owners, consistently opposed suffrage extension and social reform. One Country Party politician sneered at suffrage campaigners in 1892:

Men dominated national politics and working-class movements. Even when women joined associations, leadership was still monopolised by men. In 1870, the average adult woman in Stockholm earned only about 40% of the city’s average income. Low-paid domestic service comprised 45% of blue-collar workers in 1870 jobs - rife with exploitation, abuse, and paltry wages. Higher paid, skilled trades were overwhelmingly male, and these unions were uniformly directed at men.

So what happened next? How did Scandinavia finally get on board with equality? Why is the difference between Swedish men and women’s median wage now only 7%?

Find out in my next essay!

P.s. if you read my last essay, the answer was (B), “Contre nous de la tyrannie”.

Wow. Great article and fascinating!

A remarkable synthesis! So many relevant factors so clearly explained. Beautifully done — and quite convincing.