Why are Homicides so High in Latin America?

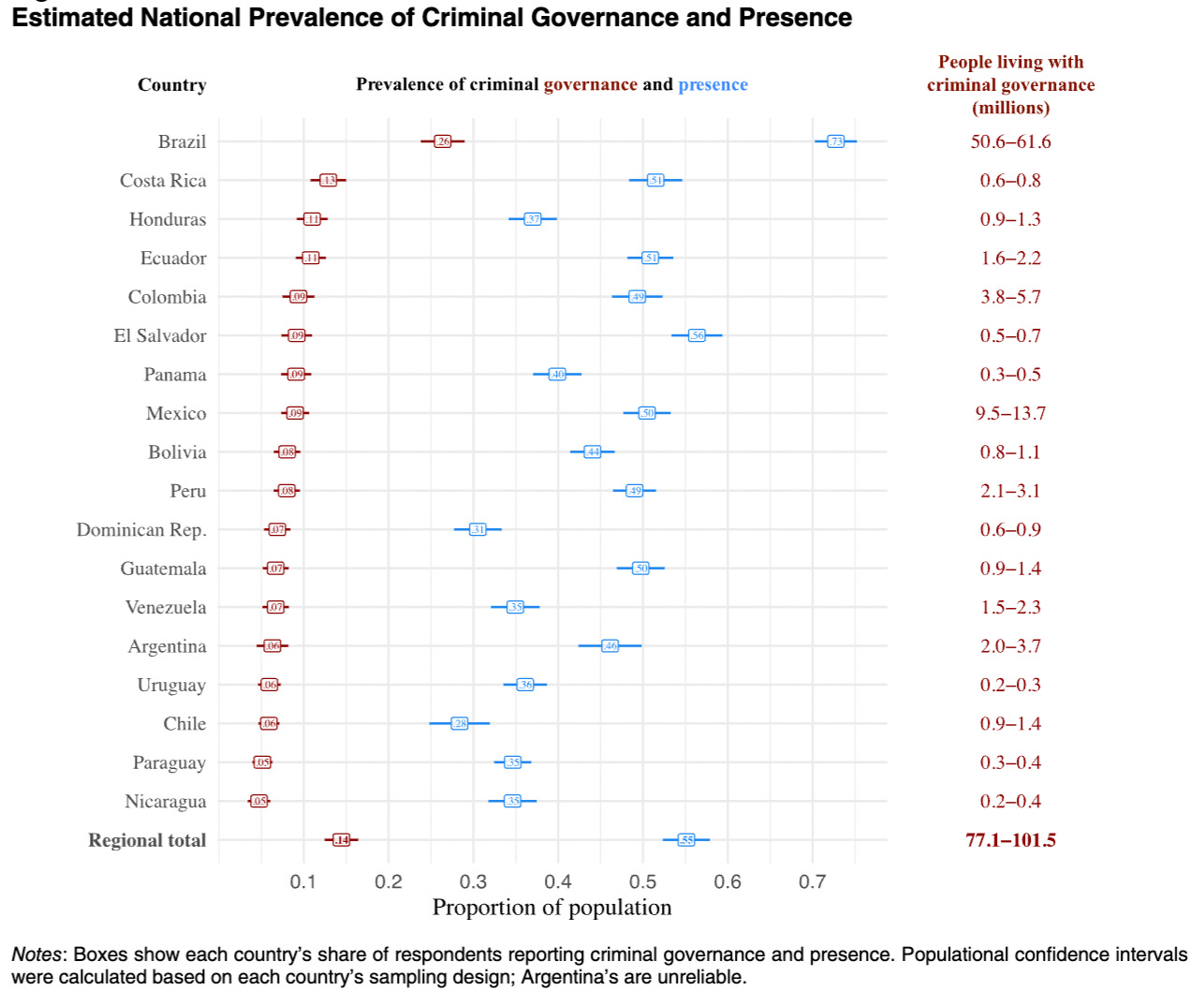

Latin America comprises 7% of the world’s population, yet a third of the homicides. Around 52-58% of Latin Americans say they live in the presence of criminal groups, while 12–16% report some form of criminal governance.

Why is it exceptionally violent? Drawing on a rich academic literature, this essay explores intersecting structural drivers:

Colonialism and slavery

Inequality & ineffective states

Extractive institutions & commodity booms

Poor urbanisation

Drug wars

Criminal governance

Before digging into specifics, it helps to consider the fundamental drivers of conflict. Chris Blattman’s book, “Why We Fight”, outlines five key mechanisms:

Unchecked interests - when criminal gangs exercise impunity and corrupt officials benefit from violence;

Commitment problems - when rivals cannot be trusted to disarm;

Uncertainty - about rivals, amid weak institutions;

Intangible incentives - like honour and respect through gangs;

Misperceptions - when psychological biases distort decision-making.

As we’ll see, all are extremely pertinent. Though I have a few additions..

Warning: this piece contains graphic imagery.

Colonialism and Slavery

In Latin America and the Caribbean, colonisers seized territories and established extractive institutions designed for wealth transfer rather than inclusive development. Authorities established exploitative labor systems including the encomienda (granting Spanish colonisers rights to indigenous labour), mita (dangerous labour in mines), and haciendas (agricultural estates), while importing enslaved Africans to regions with labour shortages. To preserve wealth, white elites entrenched their political dominance - in Brazil, electoral suffrage was contingent on literacy until 1988.

Extractive institutions, coupled with rising commodity rents, enabled soaring inequality: rising demand for minerals, coffee, and rubber enriched large landowners and industrialists, while wage growth lagged.

By monopolising political power, wealthy elites were able to advance their interests in the 20th century. Large landowners resisted land reform and maintained unproductive estates, preventing the emergence of agrarian smallholders who might have driven domestic demand for local manufacturing. Rural populations then flocked to cities, scrabbling between scarce industrial jobs and high food prices.

Import Substitution Industrialisation (1950s-1980s) primarily benefited established capitalists - who secured subsidies, credit, and market protections for inefficient, capital-intensive industries. Despite massive state investment, this delivered diminishing returns, while consumers paid high prices. When debt crises hit, governments were forced to change their growth strategy and privatise.

Amid lacklustre job-creating economic growth, organised labour remained relatively weak, while public sector expansion primarily benefits educational elites. Meanwhile, peripheral communities remain trapped in precarity, thereby reproducing inequality.

Today, Latin America still scores relatively poorly for direct taxes and state capacity.

Inequality & Ineffective States

Latin America’s extreme inequality, weak law enforcement, and inadequate incarceration may help explain contemporary violence - suggest Soares and Naritomi. The region is an outlier for Gini coefficient (measuring inequality), while compared to countries with similar crime it has lower police presence and lower incarceration rates. After controlling for these characteristics, the region is no longer an outlier.

How does inequality beget violence?

First, they suggest that when a large bulk of the population struggles to achieve upward mobility through legal means, while others have substantial wealth, this creates incentives for criminality.

Second, weak and corrupt state institutions fail to provide effective deterrence. Most Latin American countries maintain modest policing levels - 252 police officers per 100,000 inhabitants compared to 398 in benchmark countries - and lower incarceration rates (139 versus 282 per 100,000). Latin American municipalities that have implemented stronger law enforcement and supportive social programs (like Bogotá) have achieved greater peace.

When people don’t believe that the state will either protect them or provide them with economic mobility, they may turn to illicit alternatives. Solving this problem doesn’t just involve effective policing, but also credible institutions that can be trusted to maintain security and opportunity.

Poor Urbanisation

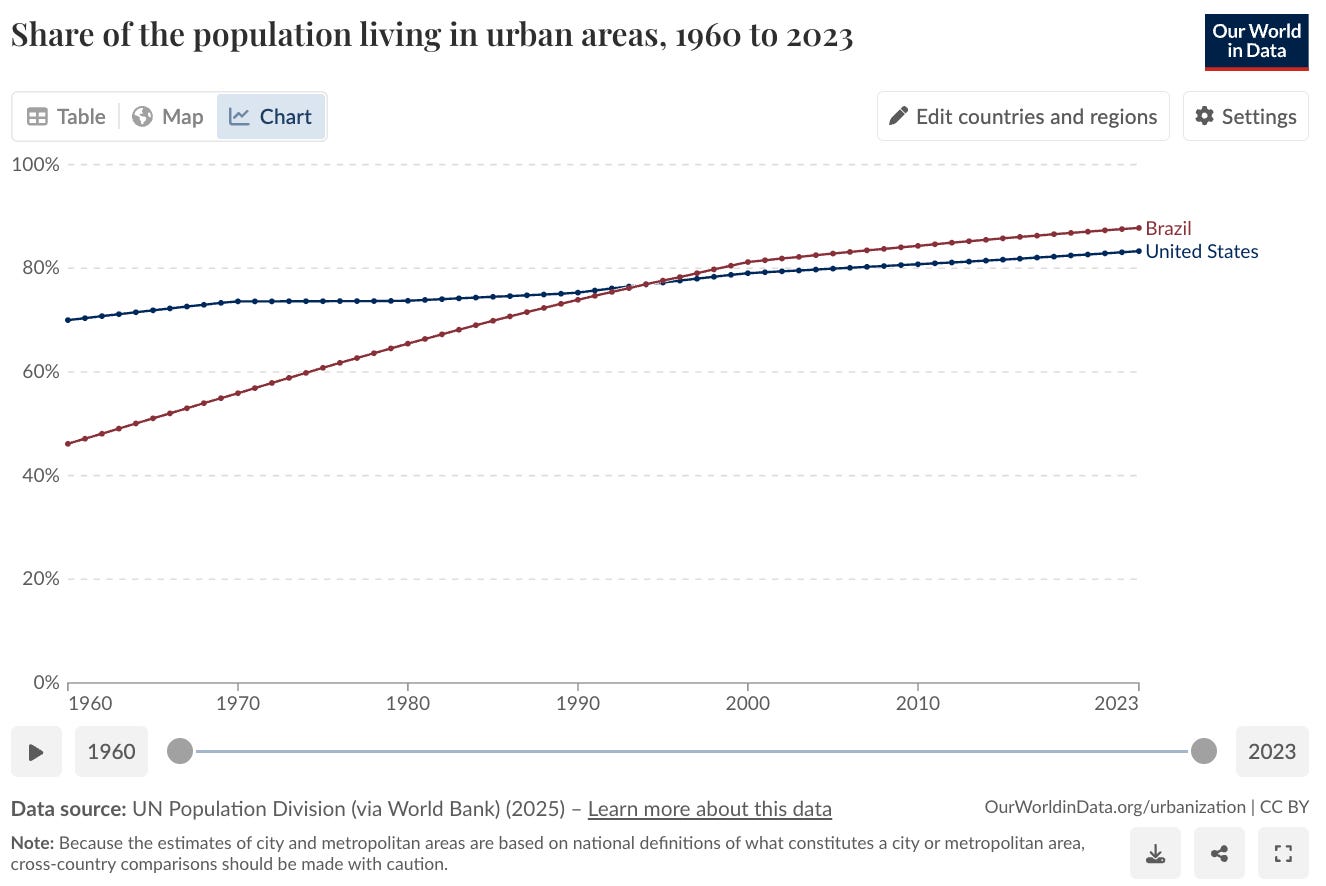

Why are Latin American states relatively ineffective? Part of the answer may be low direct taxes, caused by extractive institutions. Another factor may be what Ed Glaeser calls “poor urbanisation”: countries are now urbanising at lower levels of wealth.

Latin Americans take this one step further - achieving extremely rapid urbanisation, and now being far more likely to live in cities compared to other countries with similar wealth. Brazil is more urbanised than the U.S., at a much lower level of income.

New city-dwellers usually built their own self-help housing in unserviced favelas. Rio de Janeiro’s slum-dwelling population rose from 7% in 1950 to 22% in 2010.

Cash-strapped municipalities then face a major challenge, because urban populations are increasingly large, while public resources are restricted. Without strong urban finances, municipalities have less capacity to provide core services and enforce rule of law. This creates all the problems of the density and diversity, without the requisite institutions. Glaeser’s analysis may help explain why Latin American states struggle to provide effective deterrence.

Rapid rural-urban migration and population churn, without effective policing, may jeopardise social cohesion. In 2000, 26% of Rio’s residents were migrants.

‘Mistrust’ and ‘uncertainty’ are identified as major driver of conflict - by Blattman as well as Acemoglu and Wolitzky. Building on their work, I suggest that rapid urbanisation can be seriously destabilising. When there are massive migration flows without robust governance, neighbours become strangers, their behaviour is unpredictable, and everything is uncertain.

Blattman points to ‘cultural interdependence’ as an important precursor to peace. While difficult to measure directly, I suggest that ‘interpersonal trust’ serves as a meaningful proxy for social cohesion - and this metric is exceptionally low across Latin America. Only 7% of Brazilians say most people can be trusted. During my stay with a family in São Paulo, they warned me not to take my phone as we walked two blocks to the supermarket! Thieves cruise on motorbikes - snatching phones in the hope of accessing online banking. Just last year, a guy was shot on that same street - over his phone.

If other people’s welfare is devalued, their bodies are just obstacles, inconveniently attached to potential revenue. When a Mexican guy slammed me to the floor, smashed my head against the stone, punched me in the face, and then lunged down with a large knife, I looked into his eyes and thought:

“he does not seem to value my welfare, and might slash my face”.

With a swift maneuver, I double kicked him in the stomach, escaped and fled. Running through the favela, covered with blood (mine not his), I called for help, but onlookers just stared. Desperate to get home, I eventually hailed a rickshaw, but the driver just continued with business, stopping to pick up other passengers. Evidently, my welfare was still valued at zero.

Weak states can also lead to environmental degradation - via mining and industrial pollution, aging infrastructure, and informal recycling. Each of these can cause increase lead poisoning. This damages children’s prefrontal cortex (the brain region responsible for self-regulation and impulse control), worsening their performance in school, while raising the likelihood of suspensions and criminality. Latin America certainly suffers from elevated levels of lead exposure. Further research could examine both the effects of lead poisoning and potential solutions (see ongoing work by Open Philanthropy).

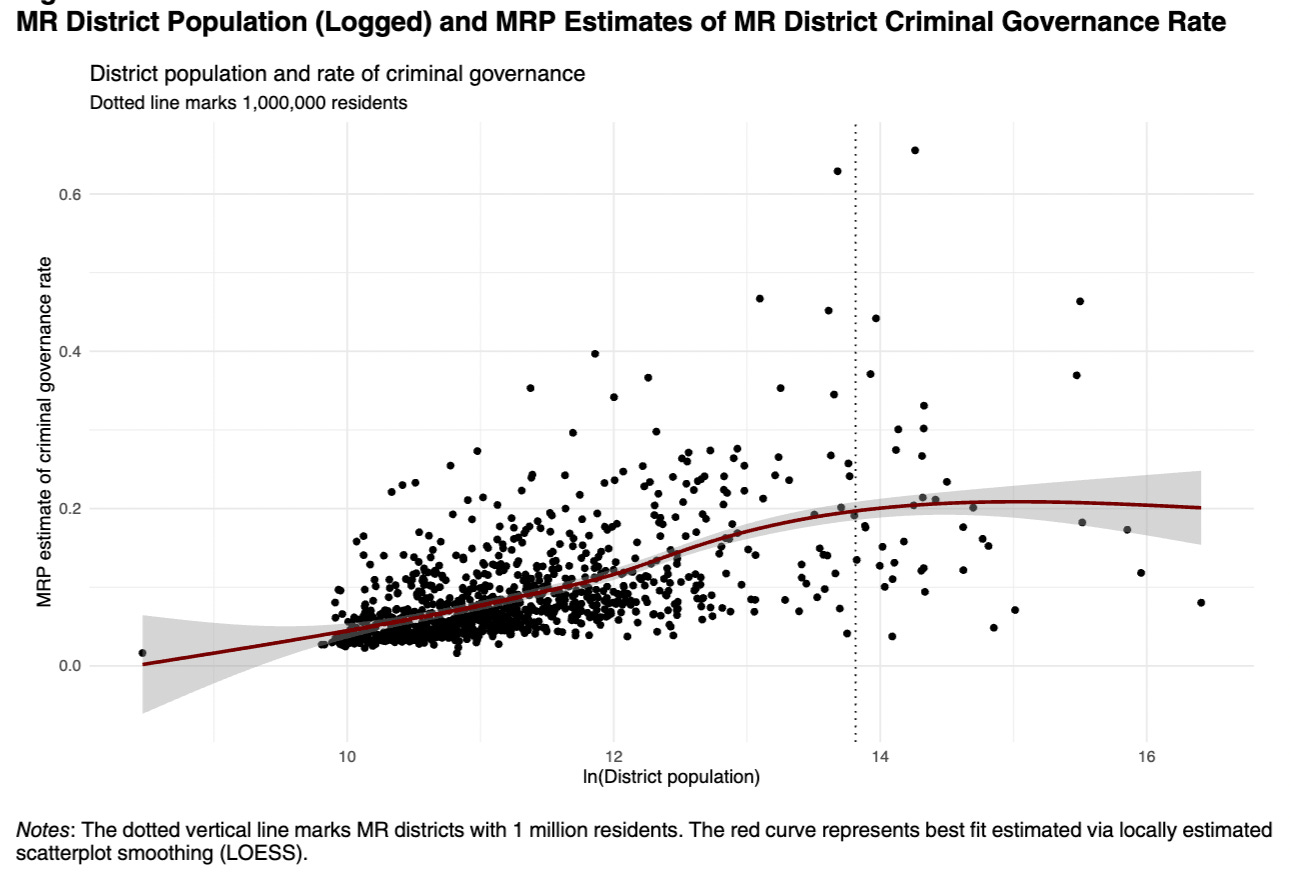

Importantly, Latin Americans only report criminal governance if they live in cities with populations over a million. This is a distinctly urban phenomenon.

Drug Wars

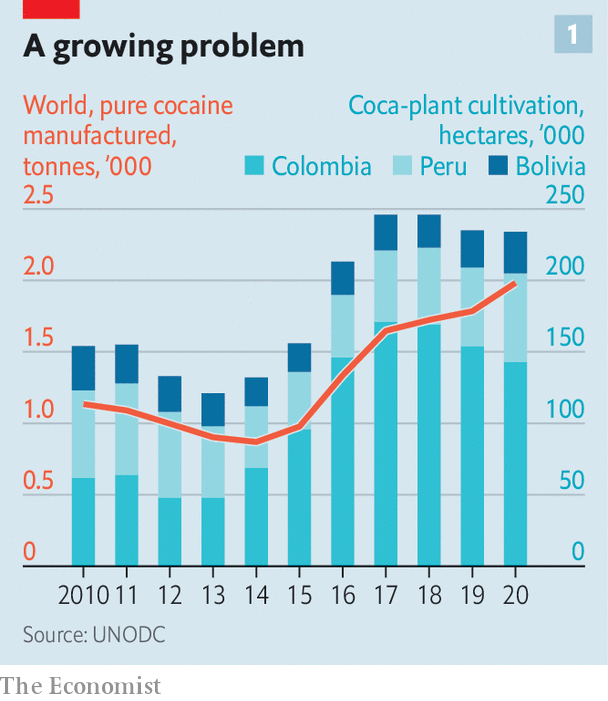

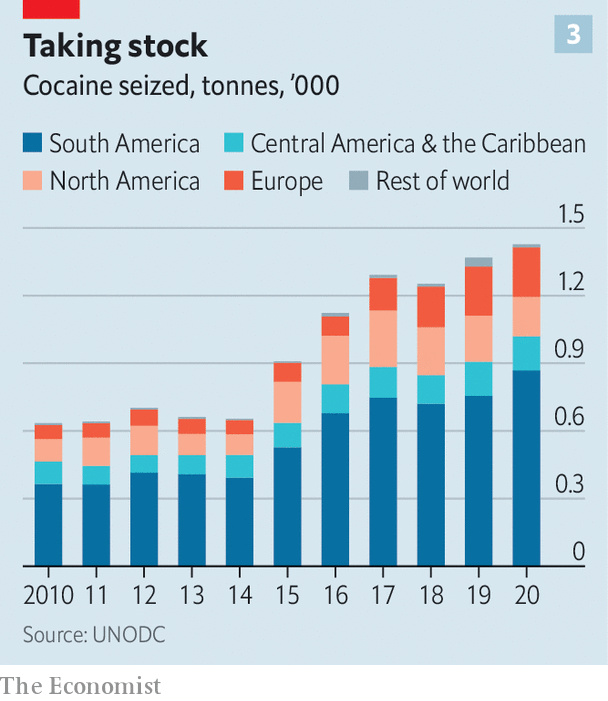

Weak state capacity exacerbates another driver of violence: European and North American consumer demand for drugs. In response, cocaine production has surged to record levels, with global output nearly doubling between 2014 and 2020 to almost 2,000 tonnes. Criminal organisations constantly adapt, innovate and fight - to capture the market.

In “Homicidal Ecologies”, Deborah Yashar shows that homicides are highest in unpoliced territories where criminal gangs compete over drug routes. Violence thus results from the conjunction of:

Weak/complicit states

Expanding illicit economies and high-stakes incentives for control of trade

Violent competition between rival organisations.

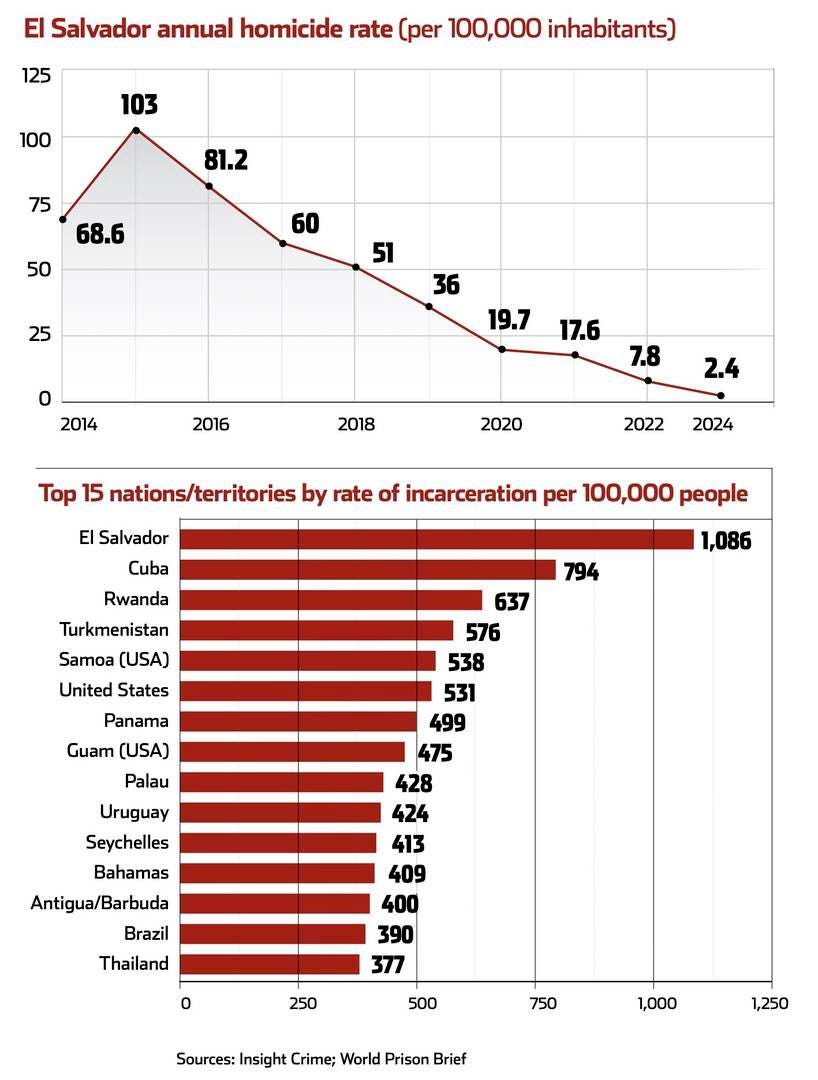

Yashar argues that homicides are comparatively lower in Nicaragua due to institutional improvements in policing, with strong prevention and pro-active community policing. Stronger state presence makes Nicaragua less attractive to drug traffickers. El Salvador, by contrast, saw an eruption in criminality.

Her theory has proved prescient!

After Colombian authorities strengthened security, and Ecuador’s leftist president ended cooperation with the US, criminal groups shifted operations to Ecuador's poorly-monitored ports, warring over trafficking routes and transforming it into a violence hotspot.

When the Brazilian government bolstered attacks on aerial trafficking, traffickers switched to Amazonian rivers - then local communities got caught in the cross-fire. Northern Brazil (where state control is extremely weak) continues to have exceptionally high homicides.

Geography - like the Amazonian jungle and Rio de Janeiro’s favelas - can also inhibit state control. Local police told me that despite technological advances (cameras and tracking), it’s very difficult to advance, since criminals scout from higher ground then lay fire from above.

Importantly, drug wars are not the sole source of friction. In El Salvador, gangs like MS-13 and Barrio 18 primarily extracted rents through extortion.

Oil Booms: Inequality amid Weak States

While inequality, weak states, poor urbanisation and drug wars may be the underlying drivers of crime, recent research has shown how shocks can exacerbate these fundamentals.

Soares and Souza (2025) explore how oil booms amplified violence, amid weak policing. During the 2000s, GDP growth was nearly 100% higher in southeastern Brazil’s oil-producing municipalities. These regions also saw major increases in inequality and violence.

What’s the possible connection?

Oil production is capital-intensive - with benefits flowing to owners and skilled workers, thereby enriching elites, while leaving the masses behind.

Urbanisation followed the boom, with a 7% increase in population density in oil-producing regions - specifically of young men.

No corresponding improvements in public goods. While local governments did receive substantial royalties and provided Bolsa Familia, this does not appear to have improved public goods. This may be due to some combination of rapid population growth; corruption; or just increased public employment without improved services.

Illicit markets may have expanded in oil areas - proxied by more drug overdose deaths. (Though this data is weaker)

Brazil’s oil boom thus increased income inequality in oil regions, creating heightened incentives for criminality amid weak policing.

Negative Economic Shocks and Jobs

Dix-Carneiro, Soares, and Ulyssea (2018) demonstrate on how negative economic shocks can drive crime. Here they exploit Brazil’s trade liberalisation in the 1990s: tariffs were reduced between 1990-1995 and then largely remained stable, while some regions were also hit harder than others.

What did they find? Regions that were more exposed to foreign competition (through larger tariff reductions) experienced BIG increases in crime. A region moving from the 90th to 10th percentile of trade shocks saw homicides increase by 46%!

But this was only temporary. Crime rates in the hardest-hit regions gradually declined to national averages by 2010. Why?

Public goods provision (government spending, police presence) and inequality are unlikely saviours, as these all continued to worsen. Dix-Carneiro and colleagues suggest that the real fix came from recovering rates of employment - with people taking more jobs in the informal economy.

To summarise this section on the drivers of Latin American homicides, colonialism and slavery created extractive institutions that perpetuate inequality and ineffective states. The mid-late 20th century heralded rapid urbanisation, but without adequate public resources. This likely exacerbated strains, mistrust and environmental hazards. Where state capacity is lacking, municipalities fail to provide basic services and maintain order. Such territories may then become captured by drug traffickers, who compete to the death.

How Should the State Respond?

Worldwide, citizens want security, but differ over the means. Where states cannot credibly promise protection, citizens turn to alternatives. Globally, support for extralegal violence (like militias) is highest in countries where there is high violence and where the political system is widely distrusted. People in areas with high murder rates also tend to support vigilanteism. That is, where the state has failed, people are more accepting of lynching.

This can breed an escalating cycle - not just between criminal gangs but also with the police. Latin American security forces tend to respond aggressively, even retaliating. In Brazil, 1 in 6 homicides is caused by the state. In 2022, Brazilian police are estimated to have killed more than 6,400 people!! Last year, one officer threw an unarmed man off a bridge.

This isn’t accidental. In Rio, new recruits are purposefully inducted with brutal training to “toughen them up”, “like pit bulls, crazy to bite people”. State violence is usually exonerated, and weak oversight sustains impunity. Only recently has the Brazilian government mandated police body-cams, to strengthen accountability.

Leftists usually decry heavy-handed “mano dura” force as excessive - as I observed at a three day feminist event in São Paulo. Black mothers shared testimonies about their sons being killed by the military police, indigenous leader (Célia Xakriabá) narrated how a peaceful march ended in her being pepper-sprayed, while politician Mônica Benício reflected on her partner’s (Marielle Franco) assassination. Together, they rallied chants against the police (“Basta de Chacina”, Enough of the Slaughter”).

Yet, on the whole, electorates repeatedly reward such aggression. 65% of Brazilians say the police have a ‘good influence’. Besieged by criminality, many are desperate for security.

“We need them!” - exclaimed Leila (a young woman, who had previously lived in a favela in Rio). “The drug traffickers invaded our neighbourhood; we want the state!!” (translated).

Yet “mano dura” can actually backfire, explains Blattman. El Salvador’s mass arrests in the early 2000s exacerbated violence. While Bukele’s crackdown in 2022 currently appears to have been effective, homicides had been declining since 2015, partly due to a prior secretive truce, which then collapsed.

Can Latin America Strengthen Security?

The evidence is pretty compelling: Latin American security hinges on building effective states capable of providing protection and enforcing commitments. Yet this path forward faces three significant obstacles

Criminal State Capture

Criminal organisations have permeated the very institutions ostensibly designed to provide law and order. Judges, politicians, and law enforcement officials increasingly operate under the influence of powerful syndicates, then selectively target certain criminal groups while protecting others. As Feldmann and Luna aptly observe, criminal networks have integrated “into the bloodstream of many societies”. I’d add, this modern corruption echoes Latin America’s history of elites establishing institutions that consolidate their advantage.

Besides state capture, a significant proportion of Latin Americans now live under some form of extralegal governance. State authority is threadbare across some low-income areas in large metropolitan areas (Rocinha in Rio de Janeiro, Comuna 13 in Medellín, Petare in Caracas), remote rural regions (Sinaloa in Mexico, the Colombian Southwest Pacific coast, Central America’s Northern Triangle) and border zones (Brazil–Paraguay, Colombia–Venezuela).

Regional Coordination Dilemmas

Criminal enterprises are just like any other firm - responding to market demand, they innovate and adapt. Just as Apple reacts to Trump’s China tariffs by moving to India, international drug traffickers are similarly footloose. When one country strengthens its security apparatus, illicit networks simply relocate their operations. Colombia’s security improvements, for instance, pushed criminal elements into neighbouring Ecuador, where Attorney-General Diana Salazar now confronts the daunting task of investigating entrenched connections between organised crime, politicians, and the judiciary. Even if her efforts succeed, criminal networks will likely migrate again, following the path of least resistance and maximum profit.

Ageing Societies

Latin America confronts a severe demographic challenge: plummeting fertility rates mean these countries will ‘get old before getting rich’, reaching high dependency ratios without sufficient economic development to support elderly populations. Demographic ageing will creates mounting fiscal constraints as economically inactive older people strain health systems and pensions. Brazil has already allocated 13% of GDP to pensions. Public resources may become increasingly scarce, forcing difficult political trade-offs between spending on social welfare and security. As productivity slows, young men will struggle to find decent (or legal) jobs.

While none of these political, fiscal and coordination challenges are insurmountable, they certainly make it much harder to establish peace and security. And where violence persists, men may continue to respond with their fists.

Looking to visiting beautiful Santiago on October, where I’m giving several talks on demographics.

Post-script: writing from my home in Little England, all I can hear is bird song and occasional church bells. On multiple evenings, I have absent-mindedly forgotten to lock the back door. Amid high trust and security, violence offers little comparative advantage. Male neighbours don’t demonstrate their bravado in fist-fights, nor do I need to partner with a macho thug for ‘protection’. Instead, I can select for sparkling comedy and loving devotion! Such safety is extremely rare in human history and, for a short little woman like me, it provides a more level playing field.

Special thanks to all my Mexican, Costa Rica, Venezuelan, Colombian and Brazilian friends who helped me so much with this research.

Great read! Lotsa useful links as well for my own writing (mostly focused on Panama), thanks for sharing :-)

Excellent article and sorry to hear about your incident in Mexico and getting punched in the face, hope you are ok after that. One aspect that struck me was the impact of trade liberalisation and the fact in Brazil, as tariffs fell, crime increased. We live in a world where we can expect global trade to change and tariffs for protected industries to reduce (such as agriculture in India, as I explore in my article, link below) could, as was the case in Brazil, this lead us to a more unequal world, which in turn is more dangerous? We hope not, but as it stands now, it looks sadly inevitable.

https://amito.substack.com/p/trade-tariffs-and-phileas-fogg?r=11ovd6