What's Driving the Global Decline in Trust?

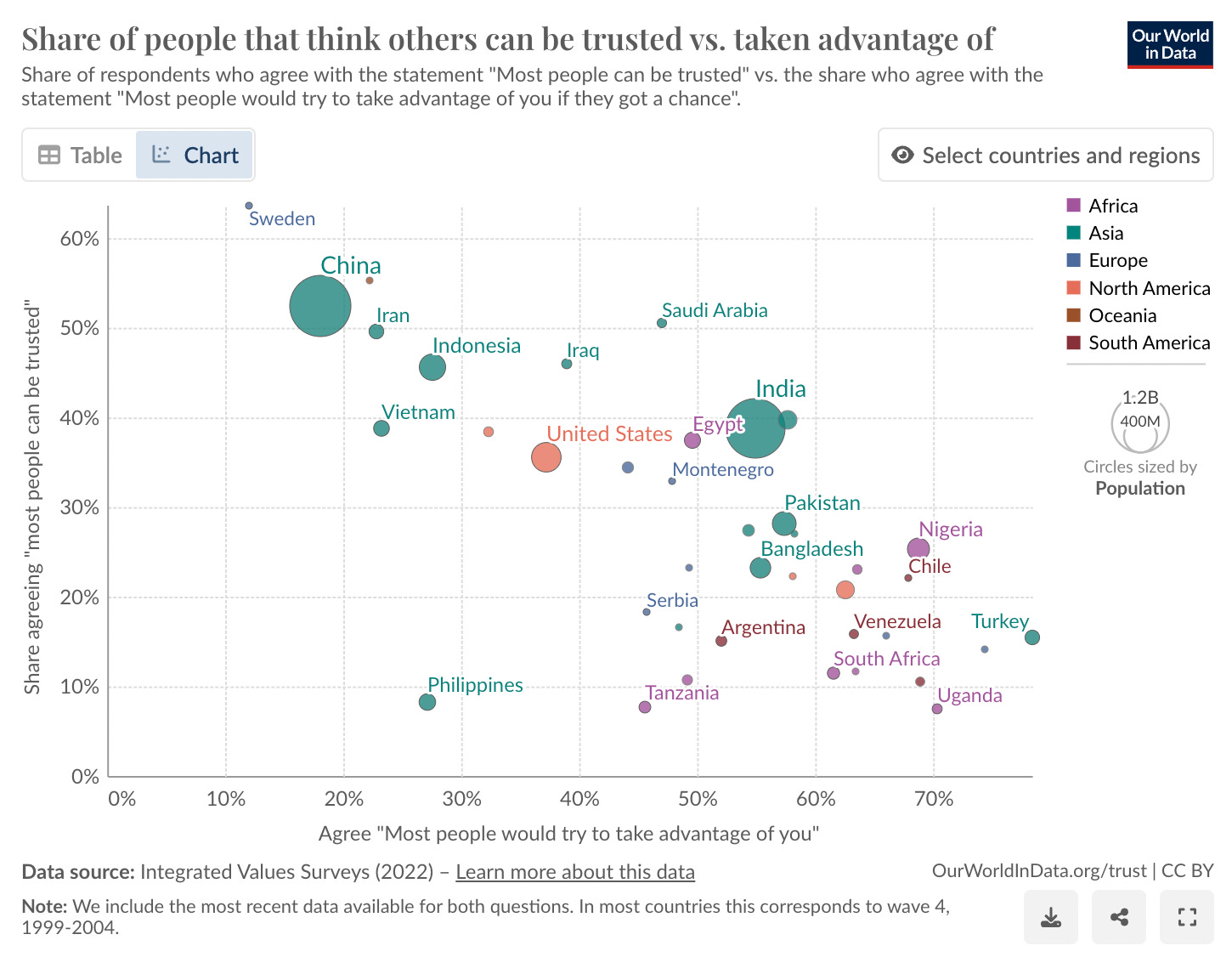

Trust is down, worldwide. In India, Iran, Indonesia and Nigeria, less than 15% say that ‘most people can be trusted’. What’s going on?

This is a two-part essay, examining the causes and effects of falling trust.

What’s causing the decline in trust?

To answer this question, we need to understand both cross-cultural variation and long-run socio-economic trends. Through my global-historical comparative research, I suggest several likely mechanisms:

Generalised distrust is correlated with strong family bonds

Poorer countries have rapidly urbanised at a lower level of income

Rule of law varies worldwide

Political contestation and growing polarisation

Online connectivity has boomed, and is increasingly negative

Culture is the first point of global variation. Strong family ties seem to be a substitute for generalised trust. A wealth of research suggests that the two are negatively correlated: one either trusts family or wider society. Scandinavia is characterised by weak family bonds and high generalised trust, whereas India has strong family bonds and low generalised trust.

Poorer countries have rapidly urbanised at a lower level of income. Cash-strapped municipalities now struggle to provide rule of law and effective services. City-dwellers are thus surrounded by diverse multitudes whom they are disposed to distrust.

Weak rule of law enables impunity for violence and exploitation. If one suspects thieves, tricksters, or sexual harassment, then cities are incredibly stressful. And where criminal street gangs murder with impunity, there is every reason for trepidation. Abuse runs rampant, wolves howl in the shadows.

Political movements vilify their foes. Group competitions are zero sum: all sides compete for supporters’ investment and loyalty. Enemies are figuratively tarred and feathered, derided as demons. In this respect, U.S. political fundraisers have much in common with Uzbekistan’s YouTube imams: hyping up external threats, while offering themselves as saviours. Political polarisation is growing worldwide.

Online connectivity is another major global trend, increasingly characterised by negativity, out-group animosity and moral outrage.

Now let me sketch the argument in more depth, starting with culture.

Kinship Intensity

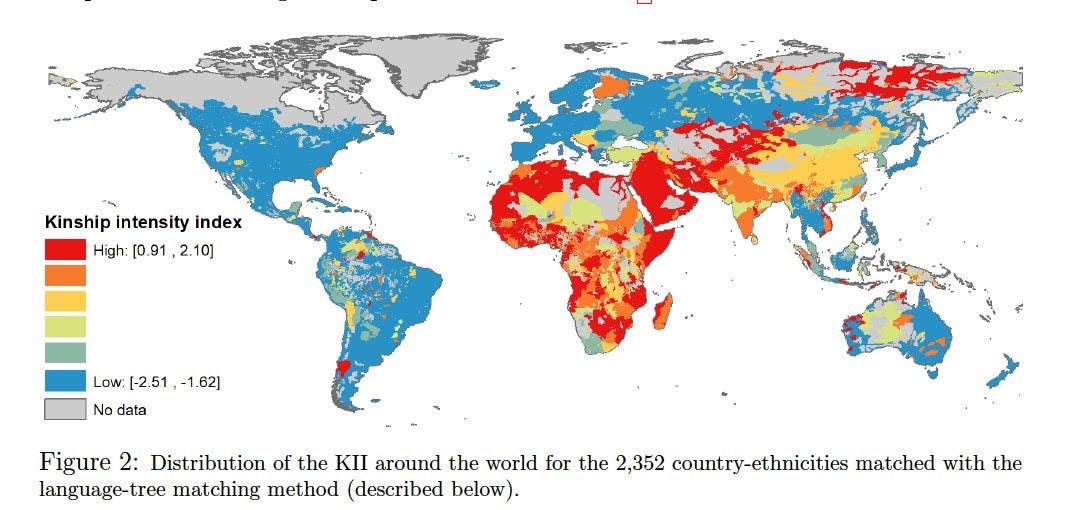

Duman Bahrami-Rad and colleagues have mapped pre-colonial variation in kinship intensity, by combining data from the Ethnographic Atlas (coding 12000 societies) and global language phylogenies. Their Kinship Intensity Index tracks norms regarding cousin marriage, polygamy, co-residence of extended families, lineage organisation, and community organisation. The Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia and South Asia all score highly.

In kinship societies, everyday life revolves around the family. Whether starting a business, seeking help in a crisis, celebrating festivities, or simply hanging out at weekends, such communities call on their kin. As a young entrepreneur explained to me in small town Uzbekistan, he trusts and hires family. Outsiders lack loyalty, they’ll leave if they get a better offer, so all that investment is lost.

Loyalty to kin is self-perpetuating - through praise, habits, and policing. Bollywood movies celebrate sons who honour and provide for their parents. This message is reinforced in daily life, aunts and uncles praise dutiful sons. Kinship loyalty is also learned through practice. If families habitually cooperate, exchange small favours and spend time with each other, they feel more comfortable with kin. Distrust in outsiders means that others are rarely given the opportunity to correct these priors.

‘Paradise lies at the mother’s feet’ is a common expression in Pakistan. Having internalised this ethic, disloyalty triggers psychological anguish. Stomachs knot in guilt. A young engineer from Pakistan was deeply in love, but when his family called on him to end the relationship and marry his cousin, he dutifully obliged. Disloyalty to kin is also heavily punished. Indian sons who disobey their parents may be vilified as pariahs. Strong familial policing means that everyone is motivated to shirk on outsiders. This reinforces strong trust in kin and distrust of outsiders.

Strength of family ties is correlated with trust in strangers

Ethnographers, sociologists, economists and social psychologists all tend to concur that family ties are inversely correlated with generalised trust. As detailed by Francis Fukuyama, strong family bonds tends to encourage small family firms. Indians tend to rely heavily on their jati-networks and live close to their kin. India’s cities (especially the smaller ones) are rife with caste-based residential segregation. Segregation by caste is actually more widespread than segregation by socio-economic status.

Urbanisation

Over the past century, the world has undergone rapid urbanisation. This seismic shift in population density and diversity may have significant implications for social trust. However, to the best of my knowledge, there is a paucity of research examining the relationship between urbanisation and trust, along with potential mediating factors.

In close-knit communities, there is strong surveillance

First consider this counter-factual. Everyone knows your name, your business, and your mother. Whatever happens, others will soon discover. So even if generalised trust is low, people may still be confident that good behaviour will be policed through community monitoring. Interdependence, social policing and threats of ostracism all motivate conformity. As a young woman from Haryana remarked, within three minutes of leaving her home, news of her whereabouts will soon reach her parents.

Weak rule of law seems to worsen urban distrust

Private urban expansion has often outstripped public sector capacity, explains Ed Glaesar. Cities grow, then the public sector builds requisite infrastructure, enacts regulation, and provides policing. Where rule of law is weak, urbanisation seems to exacerbate stress and distrust.

In mid-19th century London and Paris, injustice was pervasive - as highlighted by Charles Dickens, Eugène Sue and Victor Hugo. “Bleak House” depicts a society rife with corruption, as individuals exploit and deceive one another for personal gain. The character of Mr. Tulkinghorn, a shrewd and manipulative lawyer, gathers secrets to manipulate others, contributing to widespread wariness. “Les Mystères de Paris” by Eugène Sue, published in 1842-43 similarly gained popularity for shining a light on rampant criminality, corruption and deprivation. “Les Misérables” is now a Hollywood epic, but Hugo’s popular portrayal of a downtrodden underclass was actually based on careful ethnographic research.

In the early 1920s, Western cities enjoyed both economic boom and improved governance. England’s homicides had halved. Cities were celebrated as spaces of anonymity, escapism, and individuality. “Sister Carrie” (1900) by Theodore Dreiser tells the story of an 18-year-old who moves from rural Wisconsin to Chicago. Despite harsh conditions at the factory, Carrie is tremendously excited by her newfound freedoms:

“The great streets, the vast buildings, the brilliant shops and stores, the whole atmosphere of life there, seemed a strange thing to her, and she looked wide-eyed”

Walter Ruttmann’s 1927 avant-garde silent film, “Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis” similarly revels in the city's energy, excitement, and freedom.

Art reflected the spirit of the age. The Roaring Twenties were a triumphant age of artistic experimentation and individualism. 1920s Berlin experienced a cultural renaissance, becoming a hub of avant-garde art and liberalism. Jazz, literature, intellectual critique and art likewise blossomed in the Harlem Renaissance. 1920s Paris, meanwhile, was known as the “Les Années Folles” (The Crazy Years).

When rule of law worsens, cities are rife with distrust

In the 1970s, crime waves plagued major American cities like Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia. Fearing for their safety, residents fled, leading to a 10% population decline. As Glaesar aptly notes,

“A night on the town is much less fun when the risk of a mugging is omnipresent”.

Fear and suspicion were also rampant under totalitarian communism. ‘Enemies of the people’ were sentenced to forced labour camps (Gulags). A single misstep, even without formal charges, could result in arbitrary arrests, imprisonment, and brutal torture. While Manhattanites lived in fear of muggers, East Berliners lived in constant dread of the Stasi. The only difference was it was much harder to leave. The legacy of this era is still evident in post-communist countries, which consistently scoree highly on measures of societal distrust.

As the USSR collapsed, Russian cities experienced a surge in violent street gangs. Living in the shadow of organised crime, working class men have learnt to project brutal dominance. A ‘real Russian muzhik’ (man) is tough, strong and patriotic. Street youths may upload videos of their fights: impressing peers with aggressive physical prowess. Bonds of brotherhood became paramount - as shown in the popular 2023 Russian television series, “The Boy’s World: Blood on the Asphalt”.

Improved rule of law reduces urban stresses

Many Western cities have since undergone a remarkable transformation, thanks to institutional improvements in the rule of law, enhanced public sector capacity, and a rising demand for skilled jobs.

Perceived security is so strong in high-skilled, cosmopolitan Toronto that residents confidently walk the streets with their expensive smartphones on display.

In ‘Nuit Blanche’, communities from all over the world share their art, while Toronto’s municipal government maintains public safety. This multi-cultural overnight art exhibition is a testament to how strong institutions can facilitate diverse connections. At the Somali exhibition, I forged a great friendship with a refugee, who kindly invited me to Islamic cultural events and a local mosque.

Even if countries with strong family bonds tend to have lower levels of trust, Toronto suggests that this can be compensated for effective urban management.

Rule of law has also improved in China

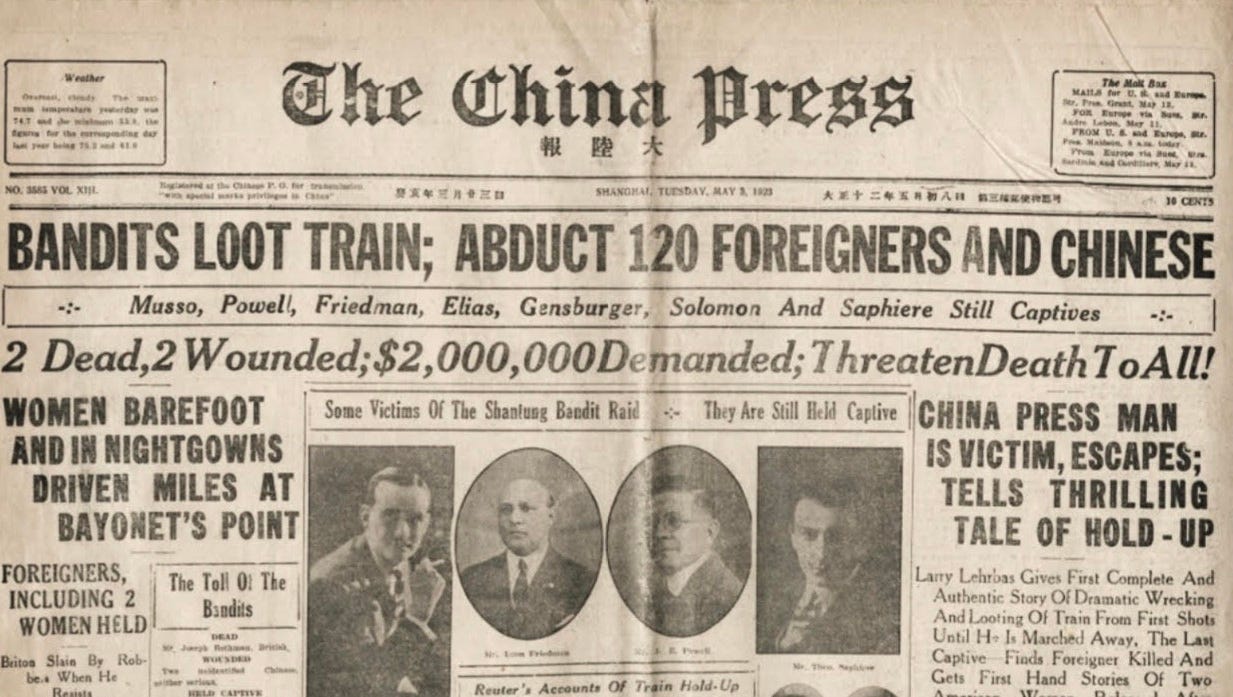

In 1923, the shocking “Lincheng Outrage” saw bandits hijack a train in Shandong province, abducting over 300 passengers, exposing lawlessness. Classic novels like Liu E's “The Travels of Lao Can” and Lao She's “Rickshaw Boy” captured widespread themes of urban hardship, hypocrisy, exploitation, manipulation and despair.

Rule of law has since improved. As detailed by Yuen Yuen Ang, Chinese bureaucrats iteratively improved governance to attract inward investment. Governance and growth both improved a co-evolutionary process.

Today, China is commonly described as a ‘surveillance state’. While many express concerns about facial recognition and authoritarianism, the flip side of the coin is low homicides. Abductions, burglaries and homicides are now rare. A woman from Shanghai shared with me that her grandparents often worried about children being kidnapped, but this is no longer the case thanks to strong policing.

None of this is to imply that Chinese courts are impartial. I merely echo a standard line from Economics: contract enforcement can reduce uncertainty.

“Poor Urbanisation”

The relationship between urbanisation and development has changed over time. Back in 1960, poorer countries were generally more rural. Fast-forward to 2010, the correlation between wealth and urbanisation was weakening. Ed Glaeser shows that countries are now urbanising at much lower levels of wealth. Most poor countries are now more urban than Korea was in 1960.

In 1900, city size was a robust predictor of living standards. Amsterdam, London and New York grew in relative size as they developed, and there was a commensurate improvement in living standards. By contrast, cities like Delhi, Jakarta and Lagos transitioned from being small and poor to enormous megacities, and yet their ranked living standards remain low.

Urbanisation can create benefits (like innovation), but it also comes with downsides. Negative externalities include contagious disease, congestion, and crime. Cash-strapped municipalities then face a major challenge, because urban populations are increasingly large, while resources are restricted. Without strong urban finances, municipalities have less capacity to provide core services and enforce rule of law. As Glaeser warns, this creates all the problems of the density and diversity, without the requisite institutions.

Now let me illustrate these tensions with examples from Nigeria, Zambia, Pakistan and Latin America.

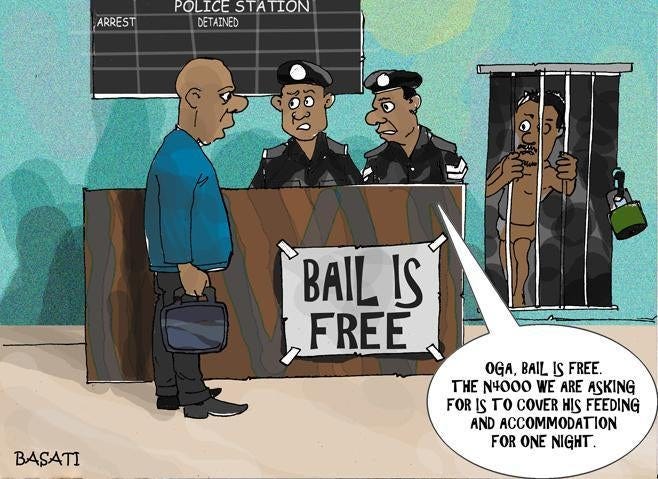

Nigeria is a prime case of ‘poor urbanisation’. It is mostly urban, yet remains poor. Lagos now comprises 17 million people (dwarfing London). City governments are run on a shoe-string, lacking fiscal capacity. The criminal justice system is stretched, and rife with impunity. In recent Afrobarometer opinion polls,

49% of Nigerians say the police rarely/never operate in a professional manner and respect people’s rights.

55% of Nigerians say they paid a bribe last year to avoid a problem

Mike Asukwo’s satirical cartoons convey the challenges of policing amid resource constraints:

Without rule of law, commerce then becomes risky. Nava Ashraf and colleagues find that Zambian female entrepreneurs

‘collaborate less, learn less from fellow entrepreneurs, earn less and segregate into industries with more women, but gender differences are ameliorated when women have access to adjudicating institutions, such as Lusaka's “Market Chiefs” who are empowered to adjudicate small commercial disputes’.

Karachi is now home to 14 million people - battered by inflation and impoverishment, without rule of law or essential services. 250 people have recently been shot dead by armed robbers. Even more people died in factory fires.

Latin America accounts for 8% of the world’s population, but 36% of homicides. In her tremendous book, “Homicidal Ecologies”, Deborah Yashar shows that homicides are highest in unpoliced territories where criminal gangs compete over drug routes. Violence thus results from the conjunction of

Expanding illicit economies and high-stakes incentives for control of trade;

Weak/complicit states

High competition between rival organisations.

Yashar suggests that homicides are much lower in Nicaragua due to institutional improvements in policing, with strong prevention and pro-active community policing. Stronger police presence makes Nicaragua less attractive to drug traffickers. El Salvador, by contrast, saw an eruption in criminality.

High homicides may help explain why Latin America and the Caribbean has always scored so poorly for social trust, and also why it’s getting worse. Only 15% of Latin American and Caribbeans say ‘most people can be trusted’.

Political Competition

Thus far I have suggested that generalised distrust is exacerbated by cross-national variation in strong family bonds, as well as growing urbanisation amid weak policing. Political competition and media connectivity may be fuelling the fire.

As everyone knows, U.S. politics and media have become increasingly polarised. When progressives rallied for Civil Rights and the Equal Rights Amendment, conservatives coalesced to form the Moral Majority. By hyping up external threats, each side seeks to mobilise supporters and fundraise for increasingly expensive elections. Democrat campaigners amp up the urgency, warning about the dangers of a Trump presidency, while Republicans emphasise illegal immigration.

In the bid for power, Trump has told thousands of lies. Fact-checkers from the Washington Post and CNN detail repeated falsehoods. After the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Donald Trump repeatedly claimed, without evidence, that the election was ‘stolen’ from him due to widespread voter fraud. In January 2021, emboldened supporters tried to seize the Capitol.

As each side tars the other side - portraying them as ‘fascists’, predators and liars - the U.S. public is haemorrhaging confidence in public institutions.

Hateful political rhetoric is hardly unique to America. BJP Karnataka recently tweeted a video alleging that Muslims would steal all the public funds allocated to Scheduled Castes and Other Backward Castes.

Political polarisation has increased more widely, especially in Eastern Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean. These trends are global, rising in the past decade.

China, curiously, has bucked this trend and trust remains high. One speculative possibility is that totalitarian surveillance has minimised both low-level violence and also the permissibility of political contestation. China’s netizens can vent frustrations against peers, but are never allowed to amalgamate or threaten social stability. Seniority within the party is not achieved by taking to their airwaves and publicly damning one’s adversaries, but carefully securing alliances (guanxi) and top-down targets.

Media horror stories may be exacerbating mistrust

Almost 5 billion people now use social media, typically spending 150 minutes a day browsing and posting. Hyper-connectivity means that we are constantly exposed to horrific events occurring across the globe. News organisations vie for our attention by highlighting tragedies, which may trigger anxiety even if they occur thousands of miles away. Politicians and cultural entrepreneurs often exploit distant threats to rally their supporters, encouraging defensive mobilisation and investment.

Research on U.S. news media and social media users suggests that the technological revolution in online connectivity is increasingly characterised by aggression, outrage and out-group animosity.

U.S. Media has become increasingly Angry and Negative

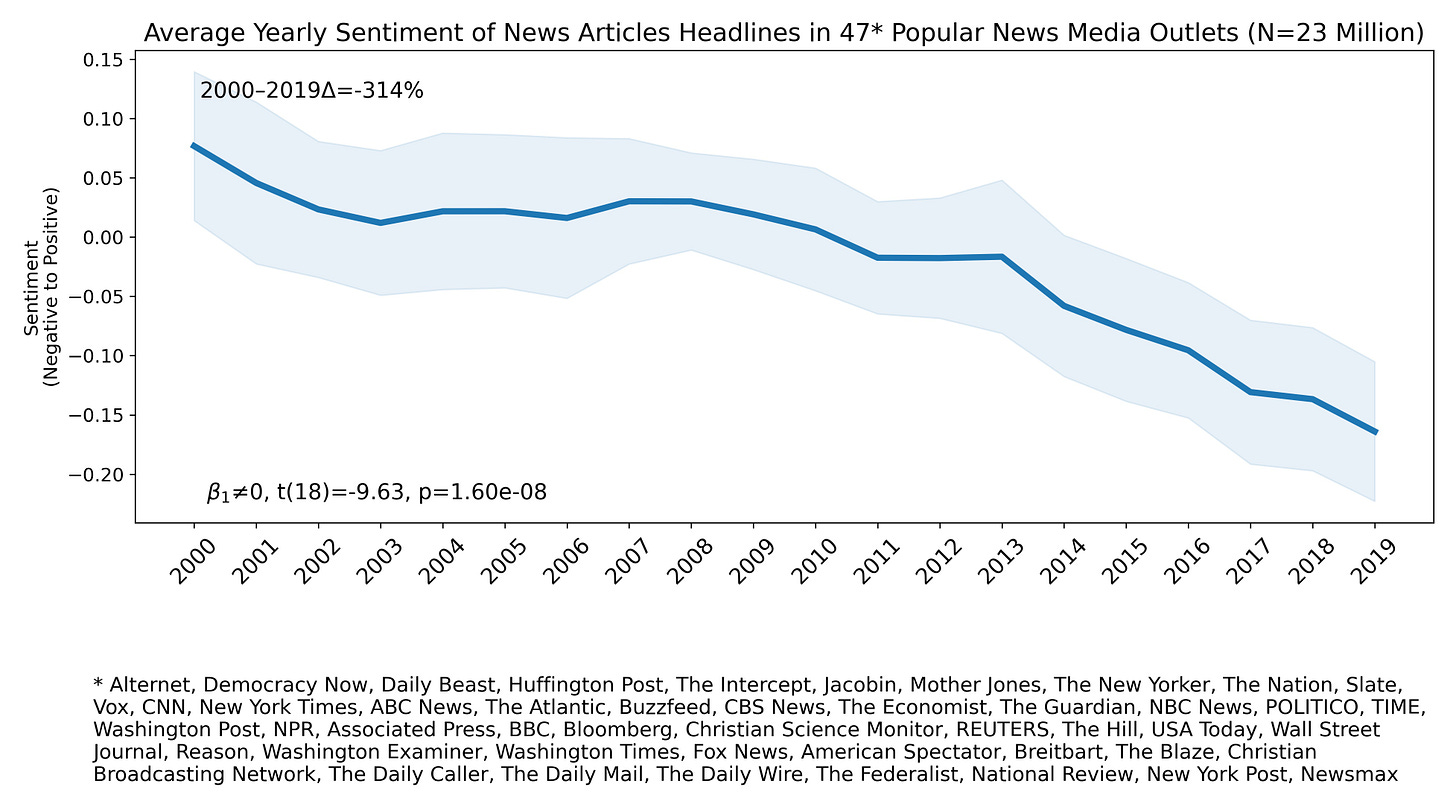

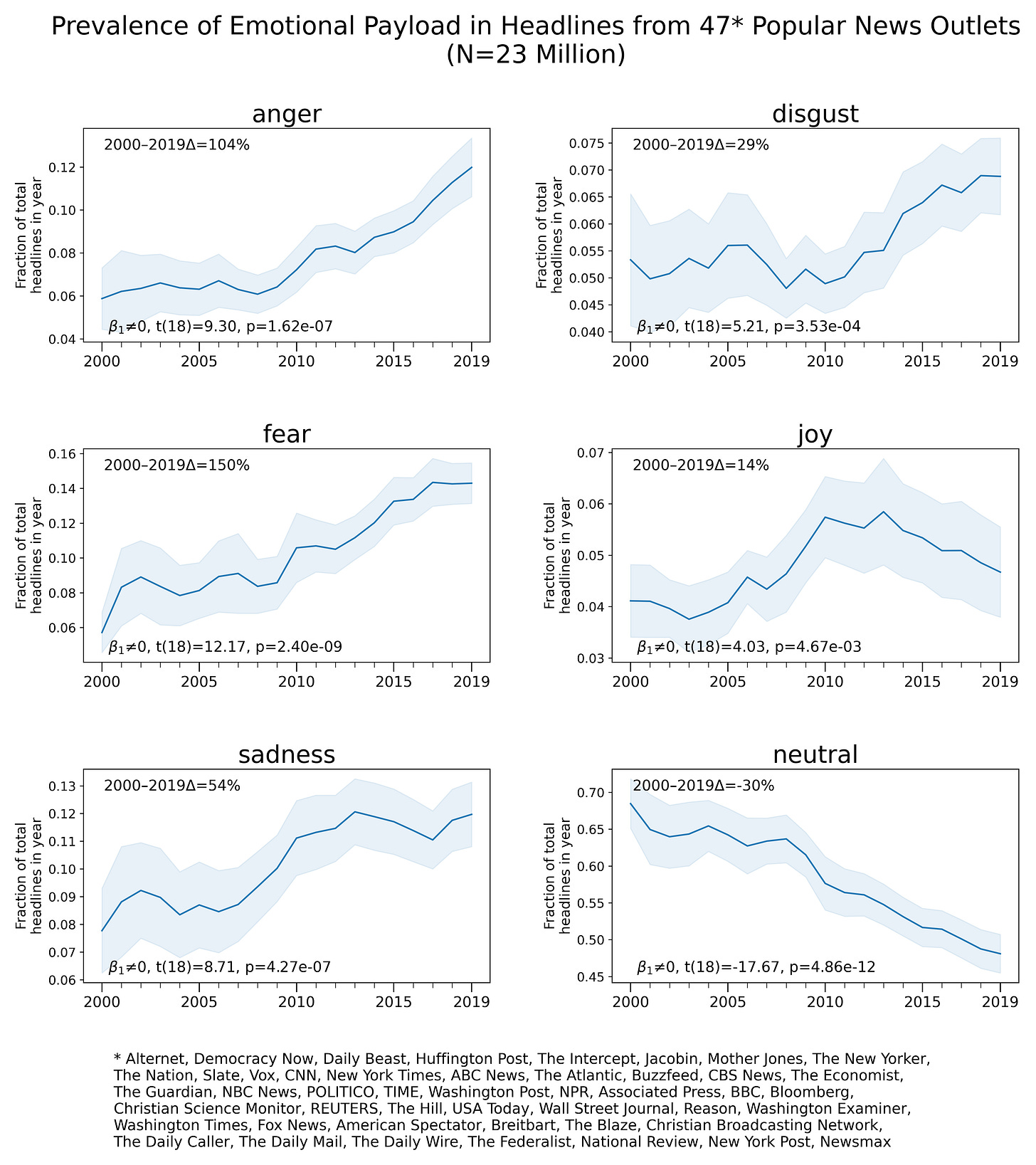

Over the past two decades, US media has become much more negative and morally outraged. David Rozado and colleagues analysed sentiment and emotion in 23 million headlines from popular 47 news media outlets. Headlines are increasingly characterised by anger, fear, sadness and disgust.

Users Reward Hostility and Moral Outrage

The proliferation of negative media cannot be solely attributed to news corporations or corporate algorithms. Humans appear inherently drawn to content that evokes strong emotions, such as negativity, out-group animosity, and moral outrage. Numerous experiments have shown that individuals are easily triggered by moral emotions, finding satisfaction in the misfortune of their opponents, demonstrating group loyalty, and vilifying adversaries. News organisations, cultural entrepreneurs and ordinary users then respond to widespread demand for moral outrage.

Social media seems to amplify perceived ideological polarisation

Claire Robertson and colleagues show that the most active media users tend to be political extremists, while moderates are more muted. Scrolling online, Americans encounter vast ideological polarisation (even if they’re only seeing the tips of two peaks). Extremist content may seem outrageous and bewildering, triggering a counter-reaction of aggressive hostility, which gets turbo-charged by algorithms.

Online connectivity increases the salience of distant threats

Quantitative researchers typically study socio-economic trends and cross-sectional variation by regressing individual- or place-based characteristics. However, given rising online connectivity, we also need to recognise the salience of distant threats. We see this play out in both German politics and Indian sexual assaults.

In the immediate aftermath of a terrorist attack anywhere in Europe, German Twitter users increasingly focused on immigrants and Muslims. This shift in discourse correlates with increased support for the far-right political party, Alternative for Germany (AfD).

Over in India, media reporting tends sensationalise stories related to sexual violence, potentially worsening pre-existing fears. Browsing the internet in May 2024, an Indian father may encounter the following headlines,

‘15-year-old girl gang raped in Uttar Pradesh’ (22/05/2024)

‘Minor girl beaten up, ‘gang-raped’ in Patna’ (20/05/2024)

’Girl Found With Hands, Legs Tied In UP, Police Suspect Gang Rape’ (11/05/2024)

‘Uttar Pradesh Shocker: 15-Year-Old Girl on Way To School Kidnapped and Gang-Raped at Hotel in Hapur’ (17/05/2024)

The message is not one of state effectiveness, but imminent danger. Accompanying graphics often depict violence. This ramps up fear.

Fears of sexualised violence lead to heightened restrictions

Economist Zahra Siddique shows that Indian media stories about sexualised violence tend to suppress female labour supply outside the home. This aligns with feminist activist Kavita Krishnan’s argument when confronted by dangers, Indian families restrict female freedoms.

The 2012 Delhi gang rape shook the nation, reinforcing widespread fears. In my interviews across six Indian states, many women told me that they had decided not to study in Delhi because they were scared:

“Our national capital is unsafe for women, no matter what caste or community you are from. And if anything happens, shame on you, blame on you” – Eesha, Delhi (Dalit journalist).

“After 2012, we felt helpless and scared to go out after dark. I didn’t want to go to Delhi to study nor did any of my friends” - Lakshmi, student from Bangalore.

Media reports of sexualised violence thus seem to perpetuate pre-existing fears of male strangers and presumptions of state incompetence. Repeating a major theme of 1980s Bollywood, contemporary reporting stokes fears of sexual predators. As Poulami Roychowdhury details, the Indian criminal justice is already over-stretched and systematically sexist. Rapes are repeatedly ignored. Given strong family bonds, unrelated men are invariably distrusted. From this low baseline, media reporting fuels further distrust. The technological revolution means that Indians are increasingly exposed to stories gruesome brutality.

As long as parents fear for their daughters’ safety, public spaces will remain male dominated. If women are nervous to venture out, they may not gain the confidence, capacities and friendships that help men navigate social and economic relationships.

What's Driving the Global Decline in Trust?

Generalised trust is falling worldwide. The question is why? Through my globally comparative historical research, I see several, interconnected mechanisms:

Distrust in strangers is correlated with strong family bonds. Loyalty to kin is reinforced through cultural celebrations and preferences for family firms. This helps explain cross-cultural variation.

Poorer countries are urbanising at a lower level of wealth, impeding state capacity for rule of law and core services.

Weak rule of law exacerbates distrust.

Political polarisation is growing, as each side seeks to rally supporters by hyping up threats and demonising foes;

Online connectivity is rising; it is increasingly negative and hostile; potentially exacerbating fears.

My theory predicts that trust is highest in societies with weak family bonds and/ or effective states, but lower and falling where there is ‘poor urbanisation’, weak rule of law, political contestation, and online connectivity.

Stay tuned for my next post on how ‘poor urbanisation’ may be generating a second Axial Age.

Further Reading:

Trust

Kinship

Violence and Rule of Law

“The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined” by Steven Pinker

“Homicidal Ecologies: Illicit Economies and Complicit States in Latin America” by Deborah J. Yashar

“Gangs of Russia: From the Streets to the Corridors of Power” by Svetlana Stephenson

Urbanisation

Political Competition

Media

This is fantastic!

I would make one minor suggestion about the persistence of social trust in China. It seems to me it's not just a matter of surveillance and low crime rates; a more important factor might be centralized control of the media narrative.

Long before smartphones existed, when I was first learning to read Chinese by translating newspaper articles, it was clear how this worked. It wasn't simply that criticism of the state was suppressed; the papers avoided anything that might acknowledge social conflict or even stimulate strong negative emotions in their readers. (They weren't really commercialized at that point so there wasn't much of a countervailing market incentive.)

It might sound paradoxical but I think you saw this most clearly in the way China handled international news. Every official newspaper limited it to a single page and presented the politics of other countries in a simplistic way, highlighting their internal conflicts without fully explaining or contextualizing them. So the foreign coverage acted as a foil, reinforcing the idea that other places faced endless problems while China was stable and prosperous.

This was all a product of authoritarianism, but before the rise of the internet you often saw a parallel style in democratic states. I can't help thinking of the atmosphere of the American media in the 1950s and 1960s: a time when public trust, including trust in the government, was (unjustifiably) very high, and when the mainstream press routinely self-censored when it came to things like criticism of US foreign policy or the personal misconduct of politicians.

The strength of China's internet controls has made it one of the few places where those media norms are still mostly upheld. Surely that's a key factor in continuing high social trust?

Strong family bonds effect on trust is mediated by low-trust vs high-trust environment, according to this paper:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/01902725231162074

The quality of institutions is falling worldwide and this might be why generalised distrust is correlated with strong family bonds