When I read quant papers on labour markets or intimate partner violence, I’m sometimes puzzled. Very few scholars are talking about the elephant in the room:

A quintessential feature of patriarchy is that men are revered as high status. They are knowledgeable authorities, speaking words of wisdom and deserving of deference. Women, meanwhile, are low status. Even though women always made important contributions to household survival and social reproduction, their work was devalued.

Do you know how the Bemba (in Zambia) describe housewives? '

‘Ukwikala fye’.

Literally, it means ‘just sitting’. She may be fetching firewood, lugging buckets of water, making fire, feeding the family, and making sure everyone is healthy. Yet that labour is totally dismissed.

Today, I want to convince you of 3 points:

Gender inequalities can only be understood if we recognise status;

If women are seen as low status, they will be expected to serve. Division of domestic drudgery are not just performances of gender, but status.

If men’s self-esteem and social respectability is contingent on them dominating their wives, they may purposefully keep them economically dependent or else beat them into submission.

To this end, I’ll present evidence from Japan, Korea, the U.S., India, Bangladesh, Uzbekistan and Nigeria. My contention is that gender inequalities are ultimately about status.

East Asia

‘Men decide, women follow’ was the Confucian model. A Korean idiom is even more explicit, ‘Man high, women low’.

In contemporary firms, female graduates are treated like secretaries, expected to pour the tea and run errands. In Japan, there’s actually a term for low-ranking female officers being expected to serve tea for male co-workers: ‘ochakumi’ (tea squad).

This is not rocket science: serving (a low status role) is done by people with low status

USA

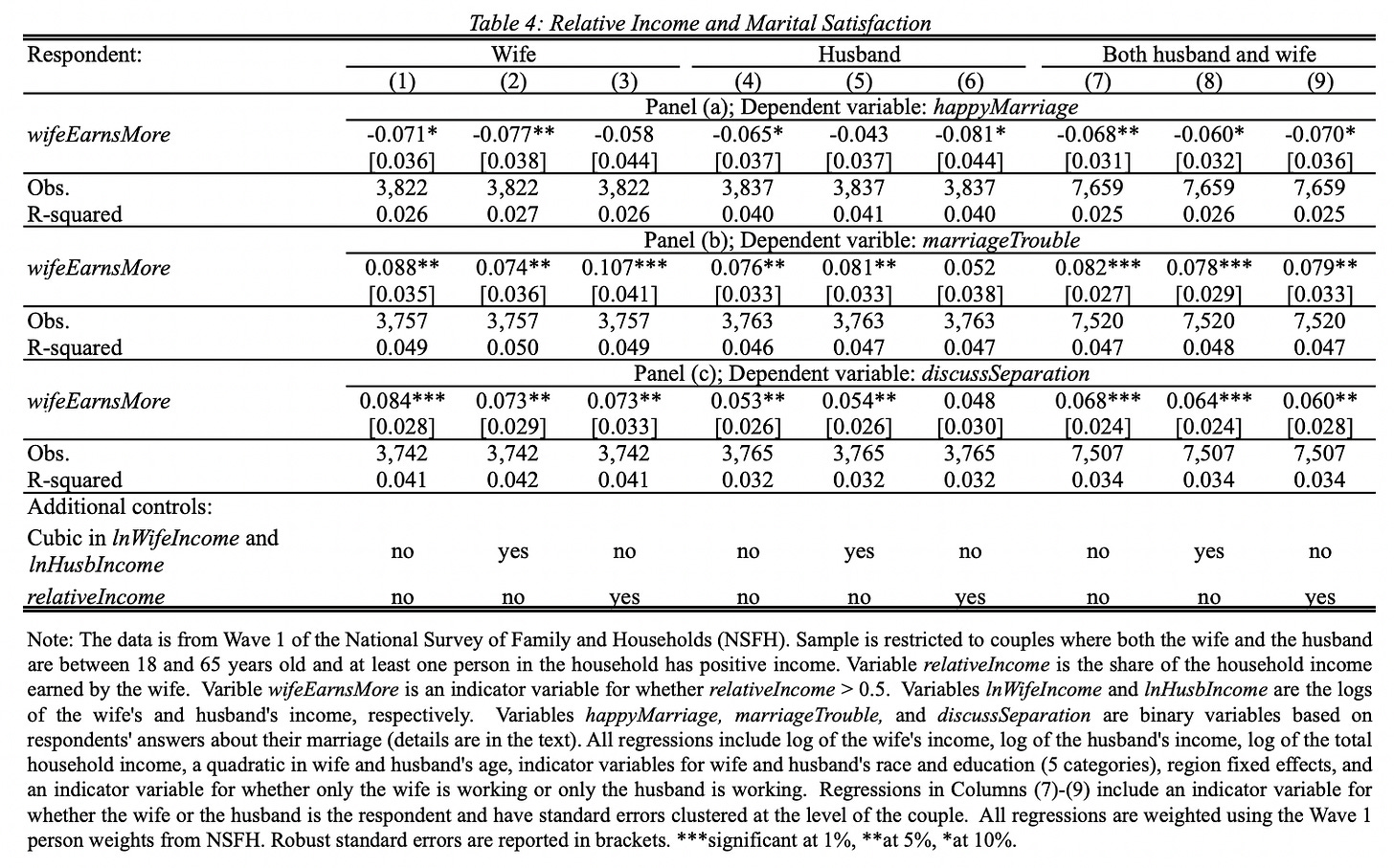

Drawing on panel data from the US National Survey of Families and Households, Marianne Bertrand and colleagues find that when the wife earns more than the husband, these couples are more dissatisfied and more likely to get divorced. The wife also does more housework.

Going against gender status beliefs creates marital discord.

India

In India today, baby boys are celebrated, while daughters are met with commiserations. Having just given birth to a healthy baby girl, one young mother in Delhi grumbled:

“I’m sick and tired of all these condolences”.

Relatives were genuinely trying to be kind, saying “Don’t worry, maybe next time”. Back at the hospital, a nearby family actually cried tears of sadness when they had a girl. Sex ratios aren’t just an abstract number, they reflect gender status beliefs about who is valued. ‘Raja beta’ syndrome refers to sons being treated like kings'.

50% of married Indian women say that their husbands have previously been controlling (e.g. limiting her movements). It makes absolutely no difference whether or not she’s recently been employed.

When poor women in Mumbai were offered jobs, 63% accepted on Day 1, but only 41% commenced work. What made them backtrack? Women discussed the job offers with their husbands. Women from less progressive households were most likely to backtrack and decline work. 42% of the housewives explicitly said they were rejecting employment due to their husbands’ disapproval. Only 28% said they were allowed to work outside the home. Just 18% said they had permission work outside their local community. Men are authorities.

Bangladesh

Likewise in rural Bangladesh, ‘women described their husbands as the primary arbitrator of whether or not they participated in any remunerated work’. That tracks representative data. Most Muslims say that ‘a wife should always obey her husband’.

Uzbekistan

In Uzbekistan, I met a young woman who married at 18. She really wanted to be a senior lawyer but her mother-in law-resisted:

“I can't let that happen, I can't that happen to my son”.

Since men are expected to be high status, it would be socially humiliating if the wife occupied a position of greater seniority.

Nigeria

In Sub-Saharan Africa, women farmers are significantly less productive than men. Male-managed farms in North Nigeria produce 46% more per hectare than similarly sized plots managed by women Why? North Nigerian men command more labour and use it efficiently. Men can tell others what to do and exploit more labour. The gender gap in productivity is much smaller in the more gender equal South.

Sub-Saharan Africa was historically land abundant but labour scarce. The major source of wealth was in control over people: ability to command labour services. Upon marriage, the groom paid the bride price to gain ownership of the children. Today, in patrilineal Niger, those with the authority to control labour are men.

Men may enforce status by keeping women dependent or through violence

If women are seen as low status, they will be expected to serve. Division of domestic drudgery are not just performances of gender, but status.

If men’s self-esteem and social respectability is contingent on them dominating their wives, they may purposefully keep them economically dependent or else beat them into submission.

In 2022, I spent a week with a driver from a village in Bihar. Travelling together to different villages, we developed rapport. I asked whether Anav would want his future wife to work?

No, partly because if she earnt money, then she would not respect me, she might be unruly…

How do you know this?

I see women who earn their own money and don’t speak to their husbands respectfully.

What would you do if your wife didn’t show respect in public?

Of course I would beat her [translated].

Economic dependency and violence were two dual strategies to secure his desired goal of dominance. Anav was mostly concerned about his public reputation: he didn’t want other villagers to think his wife lacked respect. For this reason, Anav further insisted that upon marriage he would not cook. It would reflect badly.

Gender status beliefs help us understand several features of South Asian gender relations. In Rajasthan, Punjab and Bihar, husbands are often reluctant for their wives to undertake paid work in towns. In Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, men may enforce dominance through violence. Both are means to enforce female submission.

Gender status beliefs may also help explain why female labour force participation is relatively low in Sri Lanka. Even though women are not secluded, husbands still want to maintain hierarchy.

Pakistan

TLDR

Gender status beliefs are widespread. In parts of the world where gender status beliefs are still extremely strong, men may purposefully keep their wives economically dependent or else beat them into submission. And when women achieve high status, they may encounter violent backlash.

Lastly, let me strongly recommend Cecilia Ridgeway’s excellent book, “Status”. The analysis above is mine, developed through my globally comparative research, but it’s very much inspired by her pioneering research. You may also enjoy our podcast.

I love how you present things very simply, in the form of stylized facts that are so stark, simple and coherent that they can't really be argued with. Thanks for this piece!!

Useful article and some very interesting examples. We have found similar stories in work we have done in Cambodia, Timor-Leste, Indonesia and PNG (that last one is a special case, and not in a good way). It’s interesting that in the Philippines, where gender equality has made good progress, male-centric gender norms still predominate. The status there is a bit different from your examples : men are very happy to see women in high status positions, as long as their social/cultural status remains subordinate to men. (I’m over-simplifying, of course).

When working with rural communities we often do time-studies, whereby men and women keep a timesheet for a few days. We then get together and share the results. In West Papua, we found out that women are full time busy between about 5am to 11pm (often more than this, as “getting up in night to feed baby, douse fire, shoo away dog etc.” are all apparently activities barely worth mentioning!). Meanwhile, men struggled to account for more than about 6 hours of their day. Unlike your example, men regarded “sitting about” (nongkrong) as a meritorious activity, because that’s where “important stuff” gets discussed. What stuff? Well, er, football, outboard motors and hunting.

What was interesting was that the men in no way denigrated the work of the women in household reproduction. On the contrary, they absolutely admitted that the women are doing the more important work, and a lot more of it than men. But their view was: that’s the way it should be! Women do work that is regarded as highly important, yet (as you explain well) lower status than sitting around smoking and reviewing the starting line up for FC Persipura’s next match.

Although the workshop session of revealing the time sheets was superficially good humoured, and the men were a bit shamefaced (and they admitted to learning more about the secret world of women), there was an edge to it: the women were seething.