Was the Middle East & North Africa Blighted by Bad Geography?

Islamic civilisations flourished in the Middle East and North Africa, so why did the region fall behind economically?

Political economists generally emphasise institutions. Jared Rubin, Faisal Ahmed, Ahmet Kuru all underscore religious authoritarianism. Caliphs empowered the ulama, who then preached obedience to the caliph. Timur Kuran in turn blames ‘waqfs’ - Islamic endowment trusts, another kind of institution.

This explanation seems a little unconvincing. East Asian rulers were also authoritarian, Confucian texts prescribed obedience to the emperor, and yet they have experienced rapid economic development. Confucian cultural values were neither a long-run impediment to economic growth nor democratisation. South Korea is just as rich and democratic as the UK.

What about geography?

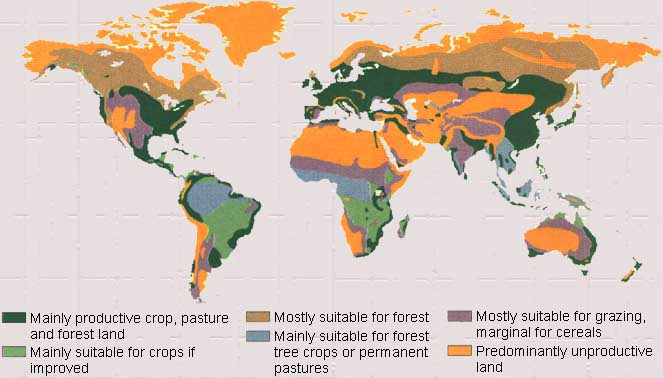

J.R. McNeil, an Environmental Historian, highlights MENA’s distinctive geography. For starters, it suffered from dearth of arable land. 90% of MENA is unsuitable for either forest or rain-fed agriculture. Since soils in Syria, Tunisia, Iran, and Anatolia were generally marginal, a 20 percent drop in rainfall could be totally disastrous.

My photos below provide a few illustrative examples of semi-arid soils in Mardin and the Atlas Mountains.

MENA’s distinctive patchwork of pastoralists and farmers

The Middle East and North Africa was historically home to herders. McNeil details that in the 1520s, a quarter of the inhabitants of Anatolia, and as much as 60% of those living in Ottoman Arab provinces, were nomads or semi-nomads. From Morocco to Balochistan, grasslands interweave through arable lands, creating a patchwork quilt, with small pockets of riverine settlements. Compared to any other world region, there would have been far more interactions between pastoralists and farmers.

Frequent interactions between pastoralists and farmers may have shaped gene-culture evolution - such as lactose intolerance. Between five to nine thousand years ago, a genetic mutation occurred, creating lactose tolerant adults. This likely spread rapidly among populations with ready access to cattle, goats, and camels. MENA’s people - most especially the Bedouins - have extremely high rates of lactose tolerance.

Cooperation could be mutually advantageous - pastoralists and farmers harnessed transport routes and pack animals to benefit from trade. McNeil suggests these synergies may have contributed to early commercial development.

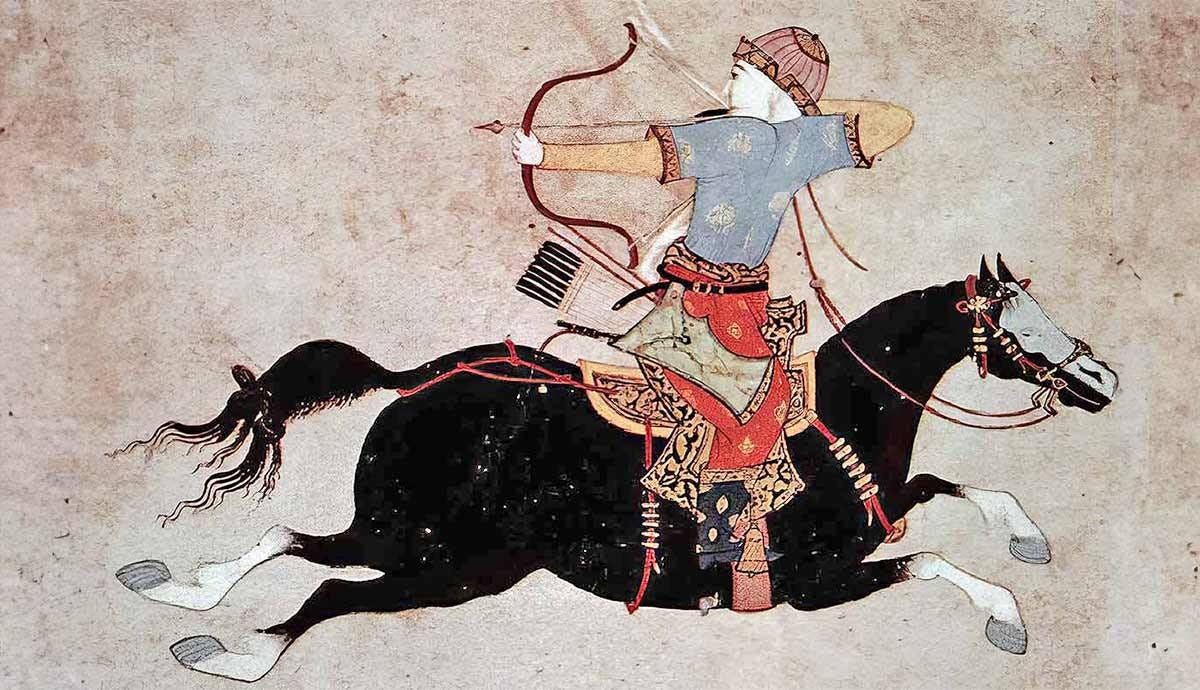

If dissatisfied with the terms of trade, pastoralists could turn to violence. Turkic archers on horse-back were formidable foes, raiding farming villages, slaughtering and pillaging, while their own women, children, and herds remained safe. Much like sea pirates, they could hit and run, escape to the hinterland.

Chinese and Indian farmers were also attacked by nomads, but only at edges of their vast agrarian economies. In East Asia, from the Qin Unification (221 BCE), large agrarian empires emerged in response to raids by pastoralist confederacies - argues McNeil, citing Peter Turchin. Globally, big agrarian empires tended to emerge where arable and grasslands met. MENA was different, it comprised a vast patchwork of interwoven pastoralists and herders.