"Freedoms Delayed" by Timur Kuran (review)

The Middle East ranks poorly for rule of law, trust, civil liberties and corruption. A quarter of its residents want to leave. Why is it so unfair and unfree?

Timur Kuran begins his new book by addressing competing hypotheses:

Islam? He insists that in Islam’s first few decades there were checks and balances.

Mongol conquests? No. Authoritarian institutions were established long before the fall of Baghdad. North African countries were not invaded by Mongols, yet are nevertheless illiberal.

European colonisation? Kuran acknowledges harms, but asks (a) why the Middle East was vulnerable to colonisation; and (b) why post-colonial Latin America has since democratised?

US patronage? Yes, but authoritarianism has far older roots.

Waqfs and apostasy rules are the real causes, argues Timur Kuran. Previously, he argued that Islamic legal institutions impeded market capitalism. Now, he blames them for Middle Eastern authoritarianism. Is he right?

Problems really began a century after Islam’s emergence, reasons Kuran. As Arab armies conquered new territories, high officials sought to shelter their newfound wealth. Drawing not on the Quran but several hadiths, they established the waqf.

A waqf is an Islamic trust, which finances designated services in perpetuity. The founder prescribes its purpose - such as to support mosques, schools, hospitals, public kitchens, and families.

The sanctity of waqfs created a safe harbour for savings - argues Kuran. Middle Easterners faced perennial threats of expropriation, given weak property rights. But Sultans generally respected these Islamic institutions and left them untouched. State officials, mamluk soldiers and clerics thus all used waqfs to evade taxes and provide for their descendents. Pre-1800s Middle Eastern buildings were often financed by waqfs.

Waqf strictures encouraged a culture of passivity

Prescriptions were laid down by the founder, which subsequent caretakers were obliged to follow. Kuran argues that strict stipulations prevented managerial autonomy; there was no room for manoeuvre. Lacking the capacity to influence the services they consumed, Middle Easterners had little opportunity for political expression.

Cooperating with other waqfs was actually forbidden. Pooling resources was impermissible. Middle Easterners were denied opportunities to jointly tackle social problems, organise collective campaigns, choose group leaders, and hold them accountable. Waqf rules thwarted liberal ideologies and capacities.

Only individuals (not groups) were allowed to found waqfs. As Kuran admits, this ‘probably lay in sultans’ aversion to autonomous private coalitions - the very consideration that excluded the corporation from Islamic law’.

If cities were served by waqfs (rather than municipalities), residents may not have seen themselves as part of a political community. Each caretaker looked after their own and there was no scope to coalesce. For Kuran, waqf rules led to to a self-sustaining political culture of inertia.

Rigidities also encouraged corruption. Islamic courts were the ultimate arbitrators; they decided whether a caretaker was complying properly with the founder’s instructions. But a judge could be bribed. Kuran argues that since Middle Eastern wealth was concentrated in waqfs, which were restricted by discretionary rulings, this encouraged widespread corruption.

How does Kuran explain Indonesia’s democracy?

If Kuran is right, if waqfs caused authoritarianism, then all Islamic countries should be authoritarian. Yet there is tremendous heterogeneity. Somalia is war-torn; Indonesia is a stable democracy. Clearly, Islam does not entail authoritarianism. There must be something specific to the Middle East.

David Stasavage argues that autocracies developed if bureaucracies could accurately predict crop yields by virtue of writing technologies, stable agriculture and irrigation. If the local ecology was rich and surrounding region was infertile, people stayed put. Byzantium, Egypt and the Sassanian Empire were all autocratic. Conquering civilisations then took over these institutions and adopted their technologies of governance.

Faisal Ahmed offers another explanation: “Conquest and Rents”. Where Islam spread via military conquest, political authority was consolidated under a dictator. Clerics legitimised the caliph’s rule and in exchange the caliph instituted sharia law, which raised the authority of the clerics. This ulema-state alliance emerged in the 11th century and was then entrenched. I suggest that religious authoritarianism likely shaped the enforcement of waqfs.

In Southeast Asia, by contrast, Islam spread through trade. Sufi clerics and merchants introduced Islam to coastal cities. Instead of allying with government, Sufi clerics often extended their reach by building alliances with traders and craft guilds (tarikahs). Malay and Indonesian villages remained relatively egalitarian, with collective decision-making.

Today, Indonesia is just as democratic as Christian Latin America.

I would add that in Muslim conquest societies, indigenous peoples gradually converted to Islam and adopted Arabic. As part of this cultural assimilation, they also adopted tribes and cousin marriage. To this day, cousin marriage remains especially high in Muslim-majority countries that were originally part of the Umayyad Caliphate.

Kuran recognises that endogamy exacerbates fragmentation. Henrich and Schulz may argue he doesn’t go far enough. Waqf rigidities may have been widely accepted by Middle Easterners, who wanted to their wealth to benefit their kin. As Faisal Ahmed demonstrates empirically, in non-conquest Muslim societies there is far greater government expenditure on general welfare. They are much less nepotistic.

Familial favouritism in the Middle East may also help explain the early decline of an Islamic institution that Kuran sees as potentially cohesive: zakat. I raise the hypothesis that close-knit kin wanted to favour their own.

What about Islam’s Golden Age?

By emphasising waqfs, Kuran insists that problems arose soon after Muslim conquests. But this chronology omits Islam’s Golden Age. The Middle East inculcated world-leading scientific discoveries, universities, collective learning and contention - notwithstanding waqf regulations.

Islamic science only declined after the ulema-state alliance, as chronicled by Eric Chaney.

What about Ghazali and cultural evolution?

When Baghdad was the seat of the Sunni Muslim empire, Persian theologians managed state institutions of learning. Transmitting Mesopotamian and Zoroastrian influences to Islam, these clerics were extremely puritanical. Since Baghdad was the wealthy Saudi Arabia of its day, they had enormous influence on Islamic ethics.

These clerics conceived of men as intellectually superior and rightful patriarchs who achieved ethical perfection by cloistering their wives. They repeatedly barred women from communal prayers in the mosque. After Ghazali, Tusi and Davani, Islam became much more patriarchal.

Ghazali sanctified not just patriarchy, but also religious persecution. Kuran acknowledges this, in his broader discussion of apostasy:

‘Ghazali helped to establish the practice of treating heterodox Muslims as apostates who deserve execution. He urged the killing of independent philosophers as well as Ismaili Shiis, insisting that rulers and their military had a duty to destroy heretics… The fatwas of leading Islamic interpreters, such as Ghazali… were collected in volumes for use by later interpreters… statesmen and judges’.

Kuran sees bans on apostasy as a core problem in Islamic history. He gives many other examples of Middle Eastern clerics and leaders who violently quashed dissent, persecuted various sects and forced religious homogenisation.

I would add several points:

Islamic institutions were not set in stone, there has been cultural evolution.

In focusing the Middle East, Kuran omits the region’s post-conquest mamluk institutions that enabled state-led religious persecution.

Allow me to illustrate with examples from Morocco and the Ottoman Empire:

Ibn Tumart, for example, travelled to Baghdad, learnt from Al-Ghazali. Upon return to Morocco, he instigated attacks on wine shops and championed female seclusion. Ibn Tumart assaulted the emir’s sister because she was unveiled. Outraged, the ulama expelled him from Fes. Ibn Tumart headed to Marrakesh, also accusing them of delinquency. Yet again, the Almoravid emir had him flogged and expelled.

Ibn Tumart found supporters, who were already Arabised. Together, they formed a religious mission of purification. In 1147, this Almohad movement overthrew the ruling Almoravid dynasty and institutionalised puritanical Islam. They rejected the Islamic principle that non-Muslims can practise their own religion but pay a tax (“jizya”). Urban Moroccans were increasingly forced to convert to Islam. Jews fled.

Ghazali became the major source of Islamic intellectual and religious authority, across the Ottoman empire. His wisdom was heavily cited in policy advice to Ottoman rulers. Under authoritarianism, scholars had to tow the line. Books of his critics (like Ibn Rushd) could not even be found in the Şehid Ali Paşa Library. In the late 17th century, there was a common saying: ‘If all other Islamic books disappeared, leaving only the Iḥyāʾ, it would be sufficient’. Mehmed Şemseddin (1883–1961), a professor of history and Islamic studies, argued that Muslim philosophy was “gravely punched by merciless and effective strokes of al-Ghazālī.”

Putting all this together helps explain Kuran’s central concerns: waqfs and apostasy bans. Islamic armies institutionalised authoritarianism, which repeatedly persecuted independently minded Muslims (like Alevis). The resulting culture of strict adherence to Islamic rules can also explain why why waqf regulations persisted, without rebellion.

Senegal has far greater religious tolerance

Senegalese Sufi marabout strongly condemn religious violence. Political and religious leaders often stress “There shall be no compulsion in religion” (Sura 256). In Popenguine, Catholics and Sufis helped build each others’ mosques and churches. In Fadiouth, Muslims contributed to the reconstruction of a church damaged in a hurricane. Ziguinchor and Fadiouth both have inter-religious cemeteries.

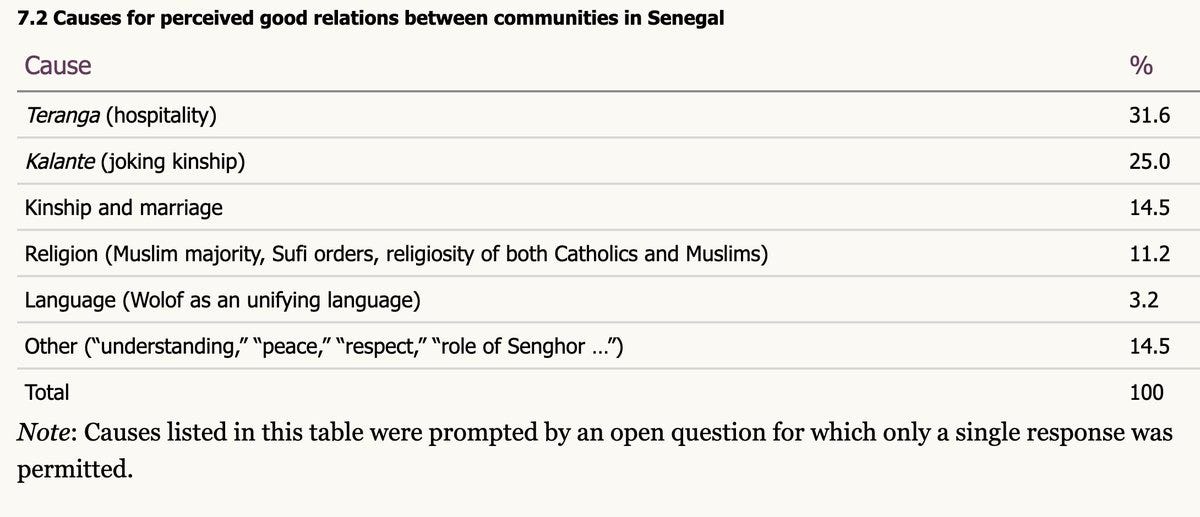

Senegalese people are accustomed to respectful “negotiated co-existence” between imams, judges and neighbourhood chiefs. “Joking kinship” enables fraternal ties across Dakar.

Senegal’s political leaders have also come from religiously diverse families and emphasised their connections to multiple ethnic groups. Maternal lineages remain important because Senegal was never under Sharia law. Bilateral succession and inter-ethnic marriage sustain a culture of open tolerance. Children recognise their multi-ethnic heritage. In Etienne Smith’s survey of Dakar:

71% said ethnicity was not a criteria in marriage decisions;

26% said religion was not a criteria in marriage decisions.

71% were open to a future Catholic leader.

Imams routinely recognise the validity of court divorces, even if these conflict with religious norms.

Until this past week, Senegal has been widely recognised as democratic. This is consistent with Faisal Ahmed’s argument that where Islam spread through trade, it adapted to indigenous institutions and accepted a culture of co-existence.

TLDR

Timur Kuran argues that the Middle East is illiberal for two reasons:

Waqf regulations hobbled civil society.

Crackdowns on heretics inhibited dissent.

Personally, I find this persuasive. But a more global historical analysis points to certain enabling conditions. Ancient authoritarianism and post-conquest mamluk institutions enabled persecution of unorthodox sects. Conquest and Arabisation also encouraged close-knit kinship and familial favouritism.

So even if Kuran is right that waqfs and apostasy bans deterred dissent, this could be endogenous to ancient and post-conquest authoritarianism, along with family ties.

Thank you for the great write up Dr Alice, it has exposed me to ideas that I wouldnt normally come across, living in an Authoritarian Muslim Society.

Stick to feminist theory. I genuinely don't mean to be mean, but seriously, both your and Kuran's claims are wholly ahistoric and eurocentric. Saying Ghazali caused apostasy laws and patriarchy, while simultaneously believing that awqaf hobbled civil society is just so bizarre and the fact you both can't see how structurally this makes no sense is why silence is a virtue. Hand waving European colonialism by saying "well, why were Muslims unable to fight back?" And not mentioning the fact that Europeans looted an entire continent and another sub-continent before they were able to fight back against the Ottomans was probably important to mention. White women log off.