Ten Thousand Years of Patriarchy!

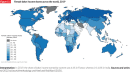

Our world is marked by the Great Gender Divergence. Objective data on employment, governance, laws, and violence shows that all societies are gender unequal, some more than others. In South Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, it is men who provide for their families and organise politically. Chinese women work but are still locked out of politics. Latin America has undergone radical transformation, staging massive rallies against male violence and nearly achieving gender parity in political representation. Scandinavia still comes closest to a feminist utopia, but for most of history Europe was far more patriarchal than matrilineal South East Asia and Southern Africa.

What explains the Great Gender Divergence? It emerged in the twentieth century as a result of the great divergence in economic and political development across countries. In countries that underwent rapid growth, technological change freed women from domestic drudgery while industry and services increased demand for their labour. Paid work in the public sphere enables women to build strong supportive friendships. They build solidarity.

Democratisation is equally fundamental. Overturning men’s political dominance and impunity for violence requires relentless mobilisation.

Culture, however, mediates the rate at which women seize opportunities created by development and democratisation. Patrilineal societies face what I call an “honour-income trade-off”. Female employment only rises if its economic returns are sufficiently large to compensate for men’s loss of honour. Otherwise, women remain dependent on patriarchal guardians, vulnerable to abuse and control.

Why do some societies have a stronger preference for female cloistering? To answer that question, we must go back ten thousand years. Over the longue durée, there have been three major waves of patriarchy: the Neolithic Revolution, conquests, and Islam. These ancient ‘waves’ helped determine how gender relations in each region of the world would be transformed by the onset of modern economic growth.

This blog offers some preliminary explorations of

The Patriarchal Revolution

Pre-Colonial Eurasia in the Longue Durée

Pre-Colonial Matrilineal and Bilateral Societies

The Divergence within Eurasia

Colonial Latin America

The Death of Matriliny

Communism

Feminist Activism

If you see an error, do correct me: alice.evans@kcl.ac.uk.

Rather listen than read? Here's the podcast.

The Patriarchal Revolution

There was no pre-Neolithic feminist utopia. If recent studies of foragers are any guide, during the 100,000 years that our ancestors had spent as hunter-gatherers, girls may have been forced into marriage, often polygynously, beaten and raped. However, since female labour is a crucial element of the forager economy, women were at least not secluded and lived alongside their own kin.

Even with the advent of early agriculture, women continued to contribute to their households by working in the fields. For example, Catalhöyük (7000 BC) was not marked by strong gender divisions of labour. Women and men performed the same work, ate the same diet, and spent similar time outdoors. Bones and burials suggest little difference in gender roles (though male violence doubtless persisted). Likewise in Bronze Age Thailand, men and women were buried with similar grave goods. In Ancient Egypt’s Old Kingdom (from 2700 BC) women had equal rights, socialized freely, supervised other female workers, and commanded respect as priestesses to female goddesses.

In the longer run, however, male dominance was strengthened by three forces: conquest by patriarchal cultures, inherited wealth amid insecurity, and religion.

1) The Yamnaya were especially patriarchal. As they conquered new territories in Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia, they institutionalised male dominance.

2) Inherited wealth was another major driver. Cattle, the plow and irrigation raised crop yields, making land itself a valuable asset. Cereals could be traded and stored.

3) Wealth turned patrilineal inheritance into a key element of social organisation. The more wealth a son inherited, the greater his reproductive success (by attracting wives, concubines and rearing offspring). But this was threatened by raiders.

4) Patrilocal lineages formed to defend valuable herds and land, as well as to provide irrigation, infrastructure, insurance, healthcare, and investment.

5) To promote intergenerational cooperation, children were socialised to privilege lineage. Close-knit patrilineal kinship spawned cultures of honour.

6) Lineage cooperation, male honour and inter-marriage alliances were maintained by controlling female sexuality.

7) As societies grew they were threatened by in-fighting. Men squabbled over women, wealth and property. Sexual jealousy may have been mitigated by religions that idealised sexual segregation, chastity, fidelity, and veiling. Compliance was promoted by praising female virtue, social policing, state laws, and moralising supernatural punishment. Male rulers and theologians blamed floods, droughts and earthquakes on disobedient women. Amid fears of eternal damnation there emerged cults of chastity. Islam became particularly patriarchal.

Cultural evolution was mediated by geography. Oceans, mountains and parasites constrained the spread of conquests, draft animals and Islam. Without these major forces of patriarchy, the Americas, Southeast Asia, Gulf of Guinea and Southern Africa did not develop patrilineal inheritance of wealth. With little concern for paternity, women could move freely, exercise authority, build independent networks of solidarity, and propagate folklore that glorified their powers.

Three waves of patriarchy in Eurasia

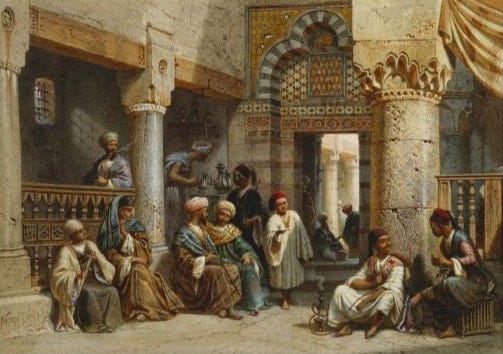

Eurasian societies became increasingly patriarchal due to migration by the Yamnaya steppe pastoralists, the emergence of inherited wealth amid insecurity, and male-organised religions (especially Islam). The stronger the reliance on kinship, as well as the greater the concern for purity, the stricter the surveillance, inhibiting women’s freedoms and friendships.

Pastoral Yamnaya raiders erupted out of the Pontic Steppe, armed with chariots, wagons, battle axes, and mounted archery. They glorified brutish masculinity, killed indigenous men, reproduced with the women, and imposed patrilineal clans. From Spain to Korea, the male line harks back to the steppe.

How do we know these population movements were important? Because societies with the exact same geography, technology and socio-economic complexity differed enormously on gender. The Minoans and Etruscans predated the Ancient Greeks and Romans. The Minoans mastered engineering, flood defences, terraced agriculture, large scale manufacturing, metal armour and maritime trade networks. Minoan paintings show women occupying prominent social positions in outdoor assemblies, fraternising freely with men. Women are depicted driving chariots, not caring for children indoors. The Gortyn code dating from 500 years after the Minoans provides further clues. Legally, women could choose their husbands, inherit property, and divorce unilaterally. Rapists were punished, but adulterous females were not. This suggests weak policing of female sexuality. Citizenship was also inherited bilaterally: if a free woman married a serf, her children would be free. The Etruscan civilisation was also technologically advanced, oligarchic, and socially stratified (between citizens and slaves). Tombs depict women mingling in public: dining with men, excelling in athletics, blessing new kings in their roles as priestesses. After these places were conquered by the Mycenaeans (Ancient Greeks) and Romans (with genetic roots and cultural assimilation from Indo-Europeans), female freedoms radically diminished.

Patrilineal kinship was imperative for the Ancient Greeks: a woman without brothers was obliged to marry her nearest paternal relative. Given strong concerns for paternity, inheritance and citizenship, wealthy families secluded female kin. Women’s names were not uttered in public; they were only recognised as appendages to husbands and fathers. As Aristotle remarked, “A man is naturally superior to women and so the man should rule and the woman should be ruled”. Ancient Greece and Rome differed from other patriarchal empires in one important respect, however: they prescribed monogamy. This idea was later adopted by the Church.

Southern Mesopotamia birthed trade, commerce and powerful city states. But none of this entailed patriarchy. State-run textile industries were staffed by female officials and supervisors. Cuneiform tablets list thousands of women (both enslaved and free) working alongside men in numerous crafts and professions.

The 2nd millennium marked a major step-change. Amorite nomadic tribes (from Arabia via Assyria) gained power in Babylon and institutionalised male dominance. This is reflected in cuneiform records, which show men's prominence in commerce, crafts, temple workshops, official roles, and family lineages. Sales, leases and loans were largely transacted by men. It was uncommon for women to exercise economic independence, unless they were consecrated to the deities. In this society, it was grossly insulting to accuse a woman of 'roaming' and 'constantly prowling', as that implied she was a prostitute. A man, by contrast, might be mocked by saying he was forced to grind his own grain, which was considered women's work. The Code of Hammurabi (1750 BC) gave husbands complete legal authority over their wives, whom could be divorced without citing a reason. Wives at serious fault could be drowned. Amorites also introduced the culture of veiling, which became mandatory for Assyrian wives as a symbol of their chaste respectability. A slave or prostitute who veiled would be punished with flogging. Later, Zoroastrianism introduced supernatural punishments, with over a third of religious sins concerning female sexuality. Women's disobedience was criminalised. The lesson from Southern Mesopotamia is that female seclusion was not entailed by geography or state-development, but spread via conquest.

About 4000 years ago, steppe migrants reproduced with the Indus Valley population to become ancestral north Indians. Together, they developed Vedic religion: differentiating between Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (kings, governors and warriors), Vaishyas (herders, farmers, merchants, and artisans), and Shudras (labourers). Brahmins topped the caste hierarchy, and today these groups have a higher share of ancestry from the steppe.

Indians have been marrying strictly within their jati for the past two thousand years. A few castes owned estates, while others engaged in pastoralism, farm work, crafts, and bonded labour. Occupations became inherited and stratified. To preserve jati endogamy, girls were married young, so they could not possibly reproduce for the ‘wrong’ lineage. Female obedience was mandated by the Manusmriti. Seclusion and son bias may have been more marked among pastoralists in the northwest and along the Gangetic plain since loamy soils allow plough cultivation, reducing the demand for women’s fieldwork, and processing wheat necessitates women’s home-based labour.

In the 7th century, Arabs conquered vast swathes of territory across the Middle East and North Africa. This catalysed a deterioration in women’s autonomy - most especially in Egypt. Conquered people gained rights and tax exemptions if they converted to Islam, recited the Quran, gained an Arab patron, and adopted tribal lineages. Patrilineal kinship was simultaneously reinforced (by Shariah law’s recognition of male agnates in inheritance and patrilineal ownership of children) and also threatened (by Muslim women’s inheritance rights). Cousin marriage provided a solution: consolidating family wealth, strength, and trust. It remains especially high in Muslim countries formerly under the Umayyad Caliphate. As Egyptians shifted from bilateral to patrilineal tribes, they restricted women’s rights and freedoms.

Iraq became the seat of the Sunni Muslim empire: Persian theologians managed state institutions of learning, and played a crucial role in developing Islamic ethics. They constructed men as intellectually superior, uniquely capable of reason, and thus rightful patriarchs. Men could only achieve piety by preventing fitna (moral corruption) and policing women. Clerics repeatedly prescribed gender segregation: barring women from communal prayers in the mosque. 12th century Damascan and Cairean women did defy these prescriptions (occasionally they even preached). But open dissent was increasingly inhibited by close-knit tribes, fear of eternal damnation, and religious authoritarianism. In the 13th century, Mamluk sultan Barsbary and clerics claimed that Egypt’s famines were Allah’s punishment for women’s unIslamic practices, they were ordered to stay at home.

The Atlas mountains and remote valleys of northern Pakistan were impenetrable, however. By escaping into rugged terrain, the Amazigh resisted Arabisation. The Kalash similarly stayed polytheistic, women exercised autonomy and moved freely.

India was ruled by Turkic Muslims for over 600 years. Mughal rule was concentrated in North India, on the upper Gangetic Plain. Women were captured in raids - sold as sex slaves. North Indian society became more gender segregated. Since the ruling class practised purdah, it came to signify status. Upwardly mobile families followed suit, to symbolise respectability. With Islamisation and the adoption of the plow, East Bengali women (once integral to wet-rice cultivation) slowly retreated to winnowing, soaking, parboiling, and husking - within the confines of the family courtyard. India is not unique in this respect, seclusion always heightens under Islam.

Male honour, supremacy and sexual segregation have been idealised in China for over a thousand years. Men preserved their righteousness and respect by confining women to the “inner realm”. Women who sacrificed themselves for honour were praised, while those who upset cosmic balance were blamed for floods and earthquakes.

But China was not always so patriarchal. When people turned away from Confucianism (after the collapse of the Han Dynasties, 220-589 CE), women were recognised for their wisdom, talents and bravery. Daoism upheld gender complementarity. And, before the advent of printing, mothers played a vital role in educating their sons. Likewise, in pre-Confucian Korea and Japan women ruled.

The cult of chastity really emerged during the Song dynasty (10-13th centuries). Sweeping away the old aristocracy, Song rulers built a meritocratic central government. Educated men competed for civil service exams, commerce boomed, cultural creativity flourished, and cities expanded. But these new opportunities were monopolised by men. Paintings of Kaifeng’s bustling city streets show porters, innkeepers, monks, and traders, but a conspicuous absence of women. Girls’ feet were broken and bound. In poetry too, women shied from public view or else were pilloried by male critics. Anonymous wall writing conveys their sadness, anxiety and abuse. Girls were increasingly killed at birth. Daughters had become exorbitant, as families competed over ideal grooms by offering ever more generous dowries. Laws entrenched male advantage: two years of penal servitude for female adultery.

Confucian revivalism was a key trigger - spread through mass printing and state exams. A burgeoning literature heaped praise on female obedience, confinement, and self-sacrifice.

Patrilineal kinship was another important catalyst. The gentry could only survive the turbulence of meritocracy, partible inheritance and violent attacks by pooling resources within their lineage. Extended families increasingly bound together to finance their sons’ education, so they might pass the civil service exam and secure upward mobility. Paying for education - as well as irrigation, infrastructure and defence - required intra-lineage solidarity. Chinese families ensured tight-knit cooperation by praising filial piety, eulogising ancestors, and compiling genealogies. To safeguard patrilineal purity and prestige, women were hobbled.

The cult of chastity heightened after the brutal Mongol invasion, during which many women were raped. Han officials sought to preserve their culture by propounding Neo-Confucianism, which Mongol rulers embraced to gain local legitimacy.

East Asian women were certainly oppressed and unfree, but they had a latent advantage which would prove important under industrialisation a thousand years later. Marrying patrilineal relatives was sternly punished under the Song Code. Exogamy weakened clans and - in comparison to the Middle East and South Asia - lessened their preference for female seclusion.

To summarise, females were closely policed to improve their marriage prospects in societies that prioritised lineage purity and honour. Although families might be tempted to supplement their meagre earnings by putting their daughter to work, this incentive had to be weighed against the potential loss of honour and the severity of social sanctions. Since no family wanted to deviate from this norm unilaterally, all were trapped in a negative feedback loop in which women stayed close to the home. Women competed over grooms with guarantees of paternal certainty: foot-binding, female seclusion, nuptial virginity tests, and infibulation.

Pre-Colonial South East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas

Oceans and parasites shielded the Americas, Gulf of Guinea and the Philippines from the three major waves of patriarchy: conquests, draft animals, and Islam. With little intergenerational transmission of wealth, women moved more freely in these matrilineal or bilateral communities. Folklore was not male-biased and language was not gendered.

In pre-colonial Philippines, land was not seen as a major source of wealth. Men paid a dowry of gold, jewellery or slaves. Daughters were valuable and divorce was common. If a woman wanted to remarry, she could take her property, half the children and half of the shared slaves. Kinship and economic interdependence much enhanced women’s bargaining power. Men even wore (painful) penis pins to enhance women’s sexual pleasure, because women insisted on it. In the 16th century, most spiritual leaders were women. Men who wanted to be priests had to dress and act like women – they had to be effeminate. For centuries, women in the Philippines, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos enjoyed pre-marital sex, travelled widely as traders, owned land, divorced freely, worked as royal bodyguards, held high office and were worshipped as goddesses.

Andean societies upheld gender complementarity. Husbands and wives were portrayed as providing commensurate labour for household survival: women’s work as weavers and cultivators was valued. Descent was traced down both the male and female line. The Moon was the supreme goddess of the Incas, worshipped as the creator of women, in a cult led by women. They also permitted pre-marital sexuality.

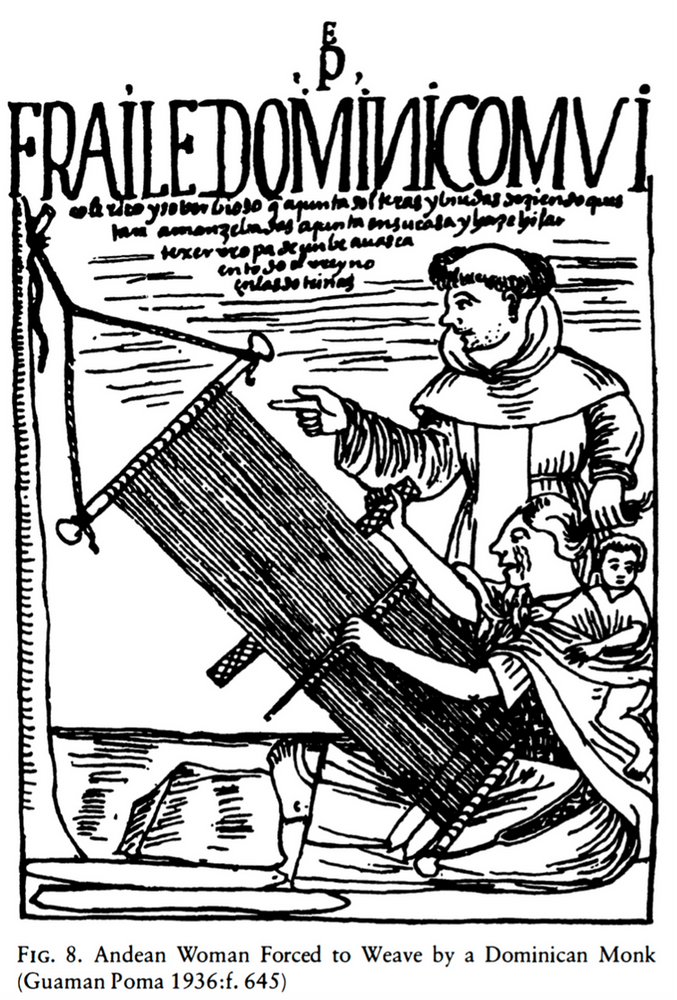

Women’s weaving was fundamental to the Inca empire. Textiles were requisitioned from commoner women as tribute; redistributed as payment for soldiers; presented as ceremonial gifts; sacrificed to the gods; dispensed to provincial lords to secure loyalty; and offered to the Spanish to build alliances. Textiles - rather than currency or land - were revered by Andeans for wealth and prestige. Furthermore, their only domesticated large animal was the llama, which can hardly be harnessed to a plough. Land never became a valuable inheritance that might enhance a son’s reproductive success. Bilateral descent thus persisted.

Sub-Saharan Africa meanwhile was mostly matrilineal, at least until 3000 years ago. This usually means greater freedom of mobility and stronger female networks - as indicated by 1930s’ ethnographies of the Bemba. Slash and burn agriculture meant there was no property to inherit, families just needed labour. To demonstrate his readiness for marriage, a young man provided his in-laws with several years of labour. Should he prove unsatisfactory, she could easily divorce and would be welcomed by kin. Women were relatively autonomous, heading their own spheres of knowledge and influence.

But matriliny is unstable, it waned with the spread of cattle. Nomadic pastoralism spread into much of Eastern and Southern Africa through male-biased migration. Pastoralists killed indigenous men and reproduced with the women. External conquest may have been motivated by primogeniture and polgyamy. If the first born son inherits most of the cattle and attracts multiple wives, younger brothers (left with little) may try to advance their status by banding together in outward conquest.

Patriliny, once established, is self-sustaining. Sons who inherit cattle wealth can attract or procure additional wives and rear more children, whose farm-work increases family wealth. Cousin marriage is often preferred, so that bride-wealth payments do not deplete the herd. Endogamy reinforces clan solidarity. Pastoralists (like the Masaii and Tswana) also institutionalised patriarchy through exclusively male village assemblies and sexist proverbs: “A team of ox is never led by females, otherwise the oxen will fall into a ditch”; “A man is like a seed, he spreads his branches everywhere”.

But cultural evolution was mediated by ecology: pastoralism could not thrive in regions infected by the tsetse fly. And when Islam spread across Africa it was predominantly among societies that owned cattle. Patoralist Fulla later launched jihads and established Sharia law.

Africa's tropical forests meanwhile were plagued by malaria. Many children died. Yet their labour was keenly sought, these communities valued “wealth in people”. High infant mortality combined with land abundance sustained perpetual demand for labour. Although societies in the Gulf of Guinea were often patrilineal, this specifically concerned control over the children (not inheritance). By paying bride-wealth, grooms gained control over the children. This reverence for fertility may help explain why women were respected as creators, and exercised moral authority as goddesses, oracles and queens.

But gender is never set in stone, it is continually contested. Women in the Gulf of Guinea only maintained their autonomy by harnessing networks of solidarity and publicly berating men who overstepped the line.

Demand for female labour certainly did not entail their autonomy. Beautiful virgins (acllas) were seized by the Inca – to become sacrifices, consecrated to the gods, concubines, or the secondary wives of provincial headmen. Commoner women were required to pay tribute in cloth, which was gifted to (male) Inca soldiers. Over in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Ashanti, Tiv, Chimbu and Igbo practised female genital cutting, female pawnship, and polygny.

Now let’s go to the Divergence Within Eurasia.

The Divergence Within Eurasia

Medieval Europe was patriarchal but possessed several latent advantages: nuclear families (without cousin marriage), participatory assemblies and state institutions. How did these emerge? Here are the facts, to the best of my understanding.

Patrilineal clans emerged in Europe as a result of colonisation by horse-riding steppe peoples.

Frankish empires blended Germanic tribes’ participatory assemblies and Roman state institutions. Both were run by men.

From 300-1300 CE, the Roman Catholic Church and Carolingian Empire tried to stamp out cousin marriage and polygamy. Noble families leveraged incest prohibitions to prevent their rivals from consolidating wealth.

English families were nuclear before the Black Death. Peasants disregarded lineage and rarely exchanged work with extended kin.

There was broad compliance with myriad Church strictures, which cannot be explained by anything but religion. In the 14th Century, English marriages seldom occurred during Lent nor if men had prior relations with her kinswoman (as was proscribed by the Church).

Young men and women often worked in service until they saved enough to establish their own nuclear households.

The age of marriage was thus unusually high in North-Western Europe (mid-twenties), especially when wages were low.

Precociously deep wage labour markets and urbanisation accelerated exogamy.

Nuclear household’s vulnerability necessitated married women’s continued employment. Husbands seldom objected. Trusting their wife’s competence, men bequeathed land and family affairs to her control. Couples cooperated, as a conjugal unit.

North-Western European women worked - as dairy farmers, spinners, seamstresses, hawkers, midwives and shop-keepers. In cities like London, Leiden and Paris, where economic opportunities were greater, market women were assertive, self-reliant and street-wise. Where guilds were weak, women gained professional pride in skilled crafts (like seamstresses in Old Regime France).

But women’s work was mostly low-skilled, unorganised and often home-based (like spinning). Before contraception, infant formula, electricity and washing machines, mothers' lives were relentlessly interrupted. 60% of their prime-age years were spent either pregnant or nursing. Screaming toddlers forestalled the pursuit of skilled trades, economic autonomy and broad social networks (beyond other similarly marginalised female kin and neighbours).

Men were far more able to seize new economic opportunities. As Europe transitioned from feudalism to commercialisation (with larger-scale more capital intensive production), men honed their crafts and travelled as merchants. Men consolidated their advantage by establishing guilds that monopolised lucrative ventures and locked women out. Men’s dominance was entrenched by a plethora of fraternal orders - in government, the judiciary, religion, medicine and universities. Vulnerable women, with weaker social capital, struggled to protect themselves from persecution. As competing Catholic and Protestant churches sought to demonstrate their superior power to protect people from witchcraft, they burnt women in their thousands.

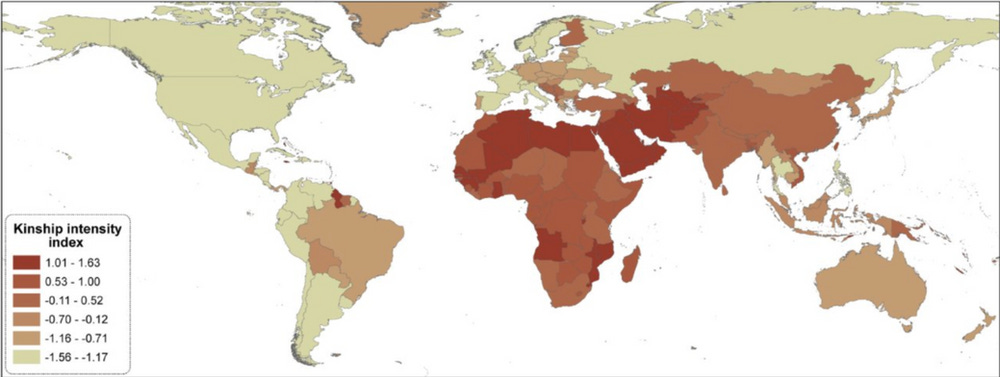

95% of writers were men, propagating patriarchal ideals. But from 1600 that started to change, starting with Protestants. Rather than defer to religious authorities (as persists across the Middle East and North Africa), Protestants championed sola scriptura: each man and woman should read and interpret the Bible for themselves. This catalysed rising literacy and gender parity; women increasingly became published authors.

The Enlightenment heralded yet greater transformation: Europe and North America became more scientific, secular and democratic. Inventors, entrepreneurs, and artisans thronged to discuss great discoveries. As peers praised innovation, others eagerly experimented and gained prestige. Taverns and coffee houses became hot-beds of collaborative creativity and political debate. Saloons were surprisingly conducive to patents! Members gained tremendous insider benefits: free-masons amassed knowledge, respectability, and elite patronage. Clubs also went to court to protect members’ reputations, enabling them to take far greater risks in the public sphere.

If you grant that this rich associational sphere catalysed innovations, surely you accept that women were disadvantaged through their forced exclusion? 95% of Enlightenment associations in England were male. Exceptions include London’s bluestocking gatherings and female debating societies, as well as Dutch women’s masonic lodges and scientific societies. But however gifted or determined, their contributions were generally derided. Brilliant women toiled in solitude, while men’s advances were amplified on megaphones.

The Ottoman empire maintained a stronger preference for female seclusion. Honour and commerce within kinship networks was contingent upon eliminating rumours of female impropriety. Clerics and concerned publics repeatedly petitioned the Sultan to crack down on women’s freedoms.

But in some respects the Ottoman Empire was quite similar to Europe and the Americas. Ordinary women worked in textiles: spinning thread and weaving cloth at home. Peasants invariably worked in family fields. Ottoman towns, however, were far more gender segregated. Hawking in busy city streets meant fraternising with non-kin, fuelling gossip, jeopardising a woman’s honour and thwarting her marriage prospects. Only the poorest, most desperate women peddled food in Cairo. Divorced women who supported their children by trading at the market could even lose custody rights. In Lebanon, baptisms only recorded boys’ names - reflecting their patrilineal primacy. Women were also absent from mosques.

Though public life was gender segregated, canny Ottoman women used Islamic courts to advance their autonomy. In 16th Century Turkey, women held independent property rights to urban and rural real estate (houses, shops, mills, orchards, and vineyards), as well as donkeys and goats. They also engaged in credit networks. In Istanbul, wealthy women founded madrasas, libraries, and religious foundations. In Damascus, women leveraged Shariah law to secure maintenance. Peasant and lower class urban Egyptian women pursued their interests in Islamic courts: trading property and pursuing thieves. 19th Century Egyptian elite women invested in businesses and litigated in court, but intermediaries operated on their behalf while they remained secluded. In Iran, imperial wives and concubines schemed to promote their sons. They were by no means passive.

Likewise in colonial India, women worked on family farms, but married early and seldom mixed with outsiders. North Indian towns were especially gender segregated. This maintained jati-endogamy, which was the foundation of trust, commerce and mutual insurance.

In sum, Eurasia underwent an important divergence: endogamy tightened in India, the Middle East and North Africa; East Asia remained exogamous; while Europe became more nuclear, democratic, and scientific.

Colonial Latin America

Spanish conquistadors butchered and enslaved Native Americans. They stole their lands and forced them onto new reservations. European epidemics wiped out entire populations. 56 million people died. Indigenous women were tortured, raped and forced to weave by colonial administrators, landowners, magistrates and clergy. They were unpaid, underfed and beaten. Family violence may have intensified under stress.

Europeans also brought horses. When Plains Indians adopted nomadic pastoralism, warfare escalated. Successful tribes grew larger and more hierarchical. The best raiders gained prestige and multiple young brides. They punished disobedience with gang rape. A major wave of patriarchy had come to America.

In the Andes, indigenous people fiercely maintained their own traditions. They kept their language, reciprocal labour, religious practices and community-sponsored festivals. Mexican Indian women continued to weave. Andean non-elite permitted pre-marital sex and encouraged trial marriage, deeming it necessary for companionate marriage. Catholic priests were aghast and threatened punishment. Spaniards decried trial marriage as ‘diabolical’. But they were ignored. The adoption of Catholicism ended their previously diverse religious roles. But women continued to work, own, inherit and bequeath property. They also participated in their local religious life and were prominent in protests. In the 1780 indigenous rebellion, women were military strategists, leading armies, organising supplies and defending territory. After the Tupac Ameru Rebellion of 1783, 43% of arrested leaders were women.

Both the indigenous populations prior to European conquest and the European conquerors themselves had relatively low rates of cousin marriage, polygamy, and extended families’ co-residence. There was variation by class and geography, however. Wealthy landowners used endogamy to consolidate property. Elite white girls were cloistered and chaperoned. Mayans were patrilineal and patrilocal, which motivated similarly close surveillance.

For the vast majority of Latin Americans, kinship was weak. In 16th century Mexico, a quarter of households were female-headed. Even higher rates were recorded in early 19th century Sao Paulo. The lower classes often formed informal unions, which broke when men left to exploit export opportunities in the agriculture frontier. Women left behind fended for themselves in home-based textiles and small shops. Men’s honour was still contingent on female chastity. But single women and widows operated independently, especially in towns where they traded in markets. In 1788, female silk spinners in Mexico City organised their own guild. Like Europe, men decided the laws of the land but kinship was relatively weak.

The Death of Matriliny

Colonialism is often blamed for the death of matriliny in Sub-Saharan Africa. Colonial officials are said to have strengthened male advantage by favouring men in agricultural training and labour markets, while Christian missions promoted female domesticity. Women arguably became more dependent on male breadwinners and lost roles as religious leaders.

But precise causal mechanisms remain unclear. Colonial bureaucracies were tiny in Sub-Saharan Africa, agricultural support was meagre, technological upgrading was minimal, and labour markets were miniscule. Imperialism did not benefit most African men, so cannot have radically heightened their advantage. Moreover, even if a few men gained temporary benefits, Southern and Eastern Africa now have some of the most gender equal parliaments in the world. This suggests that colonialism did not prevent female leadership in the long-run.

Imperialism’s strongest impact on gender was more likely indirect. Development generally leads to female emancipation, and imperialism should be blamed to the extent that it has inhibited development: imposing arbitrary borders, grouping multiple ethnicities into large states, while also catalysing violence, corruption, and authoritarianism.

The shift to patriliny was more likely a consequence of rising land values and commercialisation. The transition to patriliny was often violent. Keen to wrest control of valuable land, communities in India, South-East Asia, and Africa have hunted and killed widows as witches.

Marketisation undermines matrilocality (where a young man is a stranger in his wife’s village, working on their fields, under their authority). Once men gain wages and economic autonomy, they establish their own independent homes. But if growth is low and job queues are long, men may monopolise new opportunities. That’s precisely what happened in Northern Rhodesia. Men left their matrilineal villages to gain employment on the Copperbelt, they lived in nuclear homes. Given the dearth of good jobs, women were now dependent on male breadwinners. No society has ever got rich and stayed matrilocal.

Poverty is no feminist utopia, however. Fertility remains high in places with low returns to schooling and low opportunity costs of child-bearing. Impoverished families cannot heavily invest in all their children. Girls marry early, bear many children, become burdened by care-giving, and struggle to accumulate the capital, knowledge, and networks to challenge dominant men. Child brides are more likely to be abused. Economic desperation exacerbates stress and marital disputes.

Sub-Saharan Africa has low population density and low state penetration. If victims cannot get help, violence continues with impunity. Living in isolated rural communities, growing up in violent homes, never hearing alternative perspectives, women may try to endure what they perceive as inevitable.

Industrialisation

Britain led the industrial revolution, and with this came the male breadwinner model. After 1750, gender pay gaps widened. Mechanisation displaced women’s manual spinning.

Job queues were long and men were at the front. Firms preferred to hire, train and promote men. Women were likely to exit upon childbirth and leave early to take care of the kids. Employers would then lose their investment. In Victorian England, many teenage girls desperately wanted to work, to have a little economic autonomy and join the public sphere. Factory work was horrific, but girls still saw it as preferable to the relentless drudgery of care work, which confined them to the home, and provided no rewards. Yet their earnings were so low and the volume of housework so large that their parents didn’t consider it worthwhile. So in areas with low labour demand, girls were often saddled with childcare and scrubbing, while their brothers were out, earning their own money, and being valued as financial contributors.

Due to sex discrimination in the labour marked, women in Victorian England needed to marry to survive and remained dependent on men’s good graces, but men were distinctly unreliable. Rising male wages did not lift all boats. Moreover, they amplified patriarchy, endowing men with pride, status, and authority.

Economic growth in the 20th century eroded gender inequalities. When firms ran out of qualified men, they eagerly recruited women. Seeing growing returns to skilled work, parents reduced fertility and invested in education. Contraception, infant formula, electricity and washing machines were time-saving engines of liberation. As divorces soared in the ‘70s, marriage provided unreliable insurance and so many women ceased to rely on a male breadwinner. Career girls pursued burgeoning opportunities in medicine, business, public administration, and law.

As women thrived in traditionally masculine domains, others ceased to presume them less intelligent. Female friendships laid the foundations for feminist activism and consciousness. By speaking out, emboldening each other, gaining a sense of rightful resistance, and realising broad support for social change, women came to expect and demand better.

These changes occur if female employment rises. Women’s proclivity to move to new economic opportunities is much lower in patrilineal societies, with strong preferences for female chastity. The economic returns to female employment must then be sufficiently high to compensate for the loss of honour.

That’s precisely what happened in East Asia. Job-creating growth growth enabled women to liberate themselves from parental control. Daughters migrated to cities, where they made friends, bemoaned unfair practices, and discovered more egalitarian alternatives. They gained “face” (respect and social standing) by remitting earnings, supporting their families, and showing filial piety just like sons. Pay gaps have narrowed in Taiwan and China, just as they did in the USA and Sweden. Leveraging economic growth and democratisation, Taiwanese women closed gender pay gaps, became politically competitive, and now lead the nation.

So too in Muslim lands (like Turkey, Kuwait and Quatar), female employment has risen with tightening demand. Job-creating economic growth is a seriously under-rated engine of gender equality.

Trust in states, markets and the rule of law are also important: enabling broader cooperation (beyond kin) and lessening male bravado.

Communism

Communism may be the world’s greatest top-down intervention for female ‘economic empowerment’. Female employment is high in post-communist societies, as is gender parity in senior management. Over forty percent of Russia’s published economists and business leaders are women. Nearly half the world’s self-made female billionaires are Chinese. In East Asia, women who grew up under communism are especially competitive (as suggested by natural and lab experiments). Vietnam, Georgia, China, and Mongolia have the smallest gender gaps even in competitive chess, which in the rest of the world is a male preserve.

Socialist central planners needed women because Five Year Plans typically set high production targets. In order to supplement their low wages, women were enticed with generous maternity leave and childcare. The work book, trudovaia knizhka, was their passport to apartments, holidays and even medical care. Jobs diminished reliance on husbands not only financially but in terms of state benefits.

But if communism was so egalitarian when it came to employment, how come they’re still so sexist? In World Values Surveys, men in post-communist societies give much more patriarchal answers than men in never-communist societies when asked whether men are better political leaders; if boys are more entitled to university education; and if scarce jobs should be reserved for men.

Although post-communist countries are generally more patriarchal than comparable peers, there is a curious heterogeneity. Within Central Asia, formerly communist countries are now the most gender equal amongst Muslim-majority countries. Why might the exact same intervention advance women’s status in some places and retard it in others?

(1) By suffocating civil society, communism choked off independent women’s movements, which are vital for women’s political power and protection.

(2) But Central Asia had low potential for feminist activism, since patrilineal clans restricted women’s mobility. By decapitating religious resistance, executing dissidents, demolishing mosques, and propelling women into the workforce, Communism ended centuries of seclusion.

The Soviets tripled capital investment in Central Asia - with targets for productivity and female employees. Girls were educated in secular schools and competed in team sports. Muslim headscarfs were prohibited. Women were now graduating as doctors, lawyers, and scientists.

“I felt I was the luckiest girl in the whole world. My great-grandmother was like a slave, shut up in her house. My mother was illiterate. She had thirteen children and looked old all her life. For me the past was dark and horrible, and whatever anyone says about the Soviet Union [now], that is how it was for me” - secondary school teacher in Tajikistan.

Female employment remains high in post-Soviet Central Asia. Inequalities persist, but the counter-factual is Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan where most women remain secluded.

Feminist Activism

High female employment is no guard against male violence or misogyny. A woman may still be abused at home, harassed on city streets and locked out of politics. If men monopolise prestigious positions, others may revere them as natural leaders. Women may doubt their capabilities, be reluctant to put themselves forward or vote for others. Seldom seeing egalitarian alternatives or successful resistance, potential allies remain invisible and women reluctantly comply with a seemingly unchangeable status quo. They keep their heads down, take care of the kids, and endure patriarchal dominance.

Feminist activism is fundamental to breaking this pluralistic ignorance. In secular democracies it can spread like wildfire, igniting dissent and deviation. Urbanisation and untrammelled media are like tinder to the flame. Strolling down the streets of Buenos Aires, one realises widespread contestation. Political graffiti and viral hashtags denounce machista violence - #NiUnaMenos. Young Argentinian activists deck their wrists, necks and backpacks with the green kerchief (symbolising women’s righteous resistance). As thousands of women demonstrate for gender parity in politics, they foster feminist consciousness. Their peers come to see inequalities as unfair and problematic. When organisations secure reforms, citizens learn that they can overturn unfair laws and practices through relentless mobilisation. Sparks fly. Public dissent enables ideas to spread across peer groups. Inspired by advocates in the media, teenagers message their friends. Learning of more egalitarian alternatives, others come to expect and demand better.

Through relentless mobilisation in Latin America, women have successfully secured gender quotas, reproductive rights, and broken the silence around sexist violence. Their successes reflect three key features of the continent:

Weak constraints on female mobility (enabling rising female employment, female-headed households, and strong networks) as well

Democratisation (myriad social movements) and

Economic development (with attendant urbanisation, internet penetration, secularism, and more institutionalised parties).

That starkly contrasts with Sub-Saharan Africa (stunted by under-development); South Asia (where the dearth of good jobs has exacerbated reliance on kin, which in turn perpetuates jati-endogamy, social surveillance, and purdah); the Middle East (marred by religious authoritarianism); and authoritarian China (where dissent is silenced).

In West Africa, ethno-religious fragmentation has been an obstacle to the formation of mass women’s movements. Activists must overcome ethnic and religious divisions in order to advance their interests politically and cannot rely on an otherwise homogeneous gender-based identity. Yet women who primarily identify with their ethnicity may have little appetite for such campaigns, preferring to be governed by co-ethnics. Even if women privately support gender quotas, distrust may dampen willingness to invest in sustained mobilisation. Activism becomes sporadic.

All of this has been exacerbated by the historical legacies of the slave trade, colonialism, and the arrival of Islam and Christianity.

In the Transatlantic slave trade, 12 million enslaved people were taken from Africa to the Americas. A further 6 million were exported in other trades. In the struggle to survive, people kidnapped neighbours, family and friends.

Intensive raiding and insecurity appear to have long-run cultural effects. Africans who distrusted others may have been more likely to evade capture and then socialise their children to be distrustful. Today, distrust of relatives, neighbours and local government remains higher in places that suffered intensive raiding.

West Africa suffered most severely from the transatlantic slave trade and is now marred by acute ethnic divisions, stratification and distrust. Colonial borders compounded these effects: grouping multiple ethnicities into large states, imposing nationhood where there was none.

The politicisation of ethnicity also affects presidential responsiveness. Ghana’s leaders have always prioritised regional balance. Hence women are less likely to be appointed to African cabinets where ethnicity is heavily politicised.

History is not destiny, however. Democratisation and women’s legislative representation improve gender parity in cabinet portfolios. Urbanisation promotes ethnic homogeneity. In their absence, divisions persist and women’s movements struggle to be heard. So while Southern and Eastern African legislatures have near gender parity, West Africans are ruled by men. Nigeria’s parliament is 94% male.

Summary

Patriarchy has persisted for at least ten millennia. It has been amplified by by three major forces: nomadic pastoralists, inherited wealth amid insecurity, and religion.

Eurasia then underwent an important divergence. South Asia, North Africa and the Middle East saw tightening endogamy (caste and cousin marriage), alongside religious authoritarianism. The more visible the woman, the greater the suspicion and moral ambiguity. By preventing rumour, men preserved piety, honour, and inclusion within vital kinship networks. East Asia remained exogamous, while Europe became increasingly nuclear, democratic, and scientific. But as long as women laboured on family farms (lacking both economic independence and their own social organisations), this global variation in kinship, institutions and religion may not have made an enormous difference.

The Great Gender Divergence really occurred in the twentieth century. While female seclusion persists in poor, patrilineal countries; gender revolutions have occurred in countries undergoing rapid job-creating economic growth, democratisation, secular enlightenment, and feminist activism. For the first time in human history, women entered the labour market en masse, organised politically and collectively eroded patriarchal dominance.

And yet, in every single country and company boardroom, men remain at the top. Their first mover advantage has been entrenched through 21st century organisational practices (lucrative long hours and unaffordable childcare), homosocial schmoozing (between male bosses and juniors) and near impunity for sexual harassment. Since men are better able to capitalise on (high-paying) jobs with longer hours, they leapfrog up the corporate ladder, and then favour male cronies.

The struggle for gender equality continues. The lesson from the past ten thousand years of patriarchy is that global progress is contingent upon job-creating economic growth and feminist activism.