Yo! I’m writing another book, it’s called “The Global Development Puzzle”. That’s actually my main job. For the past decade, I’ve taught on the political economy of international development. And now, I want to share my approach to exploring these challenging questions. So here’s a taster..

As everyone knows, China has achieved remarkable success in taking millions out of poverty. However, many were still sceptical as to whether it could upgrade, innovate and export more sophisticated products. Without ‘good institutions’ (i.e. property rights and democracy), was China’s spurt short-lived?

Actually, Beijing has continued to lead major innovations and export prowess, especially in the new frontier of green technologies. What explains this puzzle?

China’s rapid ascent as a global economic powerhouse is partly due to strategic industrial policies, which have enabled technological catch-up and enhanced economic competitiveness. One of the most consequential and controversial elements of China’s policy toolkit has been ‘technology extraction’.

Technological extraction

This refers to policies that make foreign access to the Chinese market conditional on technology transfers to domestic firms. Essentially, these policies leverage China's large and growing domestic market as a bargaining chip to acquire advanced foreign technologies.

Curiously, however, China has not been able to impose these conditions uniformly. What explains this heterogeneity?

To explore this puzzle, John David Minnich employed a mixed-methods approach, combining statistical analysis of an original industry-level dataset (1995-2015) with case studies of wind power and semiconductors. Minnich ploughed through Chinese language regulations, meticulously tracking 3 types of tech extractors:

Joint venture mandates and FDI ownership restrictions,

Local content requirements (encouraging partnership and technology sharing), and

Government procurement policies, which give preferential treatment to products made by firms with Chinese investment or Chinese intellectual property.

What does he find?

Tech extractor use increased six-fold between 2002-2012, covering about 25% of all industries. (This is inconsistent with China’s WTO pledge not to condition market access on technology transfer).

Strategic industries (defined by promising the highest returns in terms of national competitiveness, principally those with great economic or military utility, which generate positive spillovers for the rest of the economy and spillover effects), account for 85% of this increase.

But even if Beijing wants to pursue technology extraction in strategic industries, its capacity to do so is limited by its relative bargaining power over foreign firms that invest in China.

Size (and positioning) matter

Minnich demonstrates that China’s bargaining power (to extract technology) is shaped by its position in global value chains (GVCs) and central state enforcement capacity. China is more likely to use tech extractors in strategic industries where it’s downstream in GVCs (as a final market), and less likely when it’s intermediate (relying on foreign firms for exports).

If the foreign firm simply wants to make widgets, it can easily do so in Vietnam, so has no compunction to make any concessions. China’s bargaining power is low (since it is competing for assembly jobs and exports).

However, if the foreign wants to profit from China’s massive consumer market, then it only has one option - to share technology.

State capacity

Institutional reforms in 1998-2003 increased ‘central enforcement capacity’.

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) gained policy authority over major projects, including large scale inward FDI. Centralisation of power enabled it to drive ‘hard bargains with foreign investors as the key gatekeeper to China’s market’.

In 2005, for instance, the NDRC agreed to buy $10 billion in aircraft from Airbus in exchange for the establishment of training facilities, local sourcing, and a final assembly line.

Minnich (2023) thus gets to the heart of China’s success: by leveraging the appeal of its ginormous consumer market, a strong and strategic state successfully persuaded buyers to share their technology, which ultimately enabled local technological upgrading!

China’s massive population and position in global value chains augmented its bargaining power to extract technology.

Revving Up the Local Car Industry!

In just a few decades, China transformed from having virtually no domestic car production to becoming the world's largest automobile market. How did Beijing achieve this remarkable feat?

Again, the Chinese government required foreign carmakers to form joint ventures with domestic firms in exchange for market access. If a US company wanted to sell in China, it had to share its technology.

To investigate this policy’s effectiveness, Jie Bai, Panle Barwick, Shengmao Cao, Shanjun Li examined how quality improvements in specific dimensions (e.g. engine performance, fuel efficiency) spread from foreign joint ventures to domestic automakers. They found:

Strong evidence of knowledge spillovers from joint ventures to domestic firms, especially for companies that are part of the same business group. When a joint venture improves quality in a particular area, affiliated domestic brands show similar improvements.

Proximity also matters. Firms located in the same city as joint ventures benefit from spillovers even without formal affiliations, as they may have the same parts suppliers, and China has extremely high labour mobility, enabling the dissemination of valuable skills.

Modelling exercises indicate that without the joint venture policy, the quality of domestic brands would have been about 12% lower by 2015. However, geographical effects appear even more important, accounting for a 29% quality gap (Bai et al. 2020).

The Electric Vehicle Revolution: China's Evolving Strategy

Building on its success in the traditional automotive sector, China has recently orientated its industrial policy towards new green technologies.

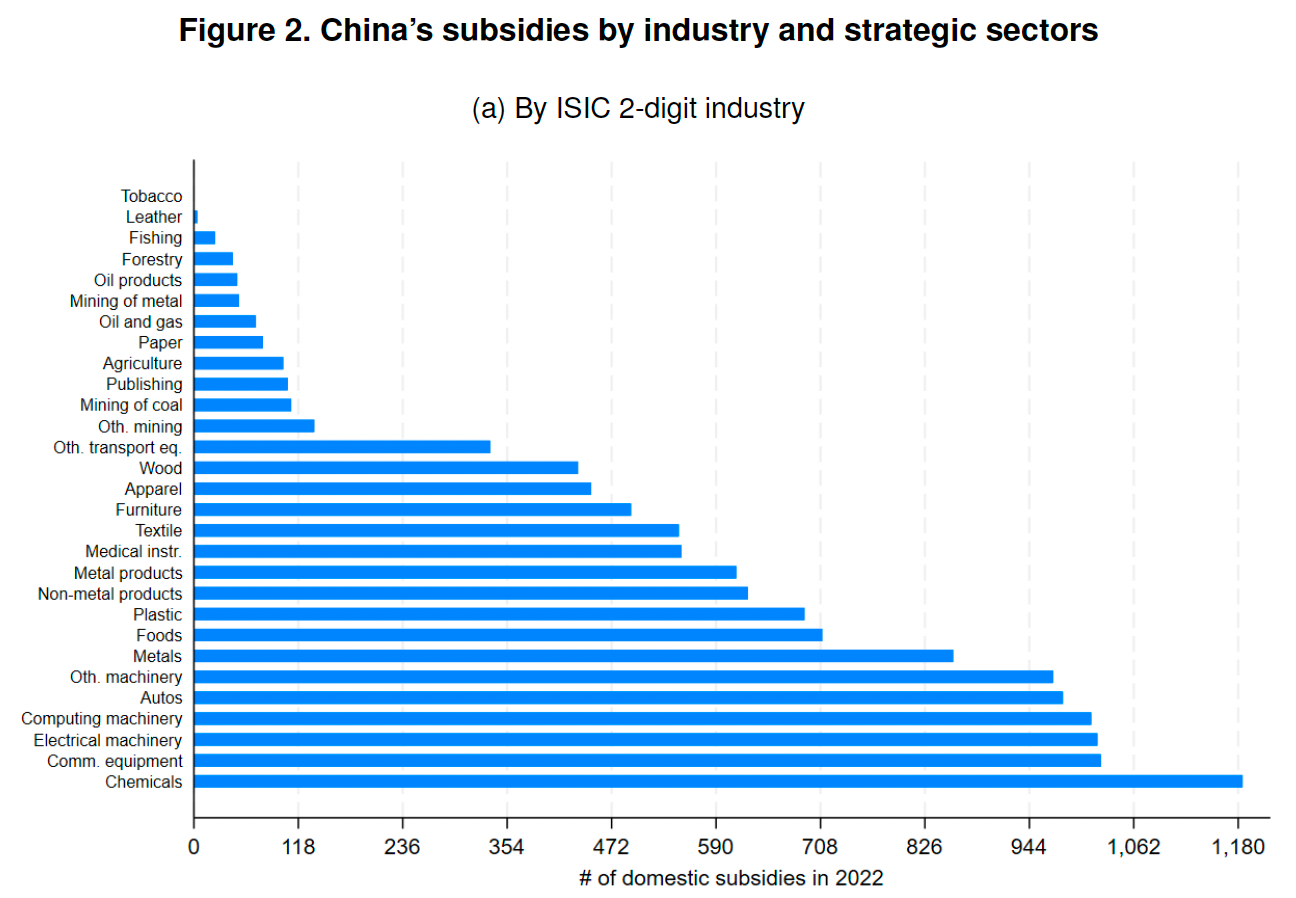

Subsidies for Electric Vehicles have shot right up.

Initially, the Government China focused on stimulating EV demand through consumer subsidies - of up to $8,500 for private pure electric vehicles and up to $71,000 for public electric buses. This pilot was expanded to more cities, establishing market interest in EVs (Wu et al. 2021).

Interestingly, Chinese consumers could use these subsidies to buy imported electric cars, such as from General Motors and Ford. Local firms were thus exposed to global competition (instilling market discipline).

But on one condition..

Foreign firms had to share key technologies with Chinese companies. Back in 2011, for instance, General Motors divulged that its Chevrolet Volt would only qualify for Chinese subsidies worth up to $19,300 a car if it agreed to handover the engineering secrets to a Chinese joint venture… Companies like Ford, Nissan, Toyota, Volkswagen have spent billions on developing electric cars, and were eager to profit from China’s consumer market.

From 2016, consumer subsidies became conditional on using batteries from Chinese owned factories (Bradsher 2024). By encouraging these technology transfers, Beijing gave its producers a helping hand.

From 2016 to 2020, China transitioned towards more supply-side policies, introducing new incentives and regulations targeting manufacturers. This new system sets increasingly stringent targets for manufacturers, requiring them to produce more EVs and improve the fuel efficiency of their conventional vehicles. By 2023, the policy mandates that 18% of a manufacturer's fleet must be new energy vehicles (Wu et al. 2021).

One more thing! The state also subsidises steel, a main supplier of inputs to the car industry. Rotunno and Ruta (2024) find targeting upstream industries made downstream industries more globally competitive. Cheaper steel is great for BYD!

Beyond Subsidies: Comprehensive Support for the EV Industry

Beijing also supports industry by providing cheap land for factories, highways for freight trucks and bullet trains.

Labour repression is another way in which Beijing keeps factory costs low: independent labour unions are banned. Illicit organisers would be detained.

Human capital is equally pivotal. Edward White reports that in 2020, China had 3.6 million STEM graduates (compared with 820,000 in the US). Chinese company BYD now employs 100,000 people in research and development. On average, BYD research apply for 19 new patents every single day.

It’s worth noting that within China, there is significant regional heterogeneity in EV adoption. Shenzhen, for instance, has achieved far greater success than Suzhou. Gomes, Pauls, and ten Brink (2023) suggest this is due to coordinated governance, ensuring the requisite charging infrastructure. They underscore the importance of state capacity.

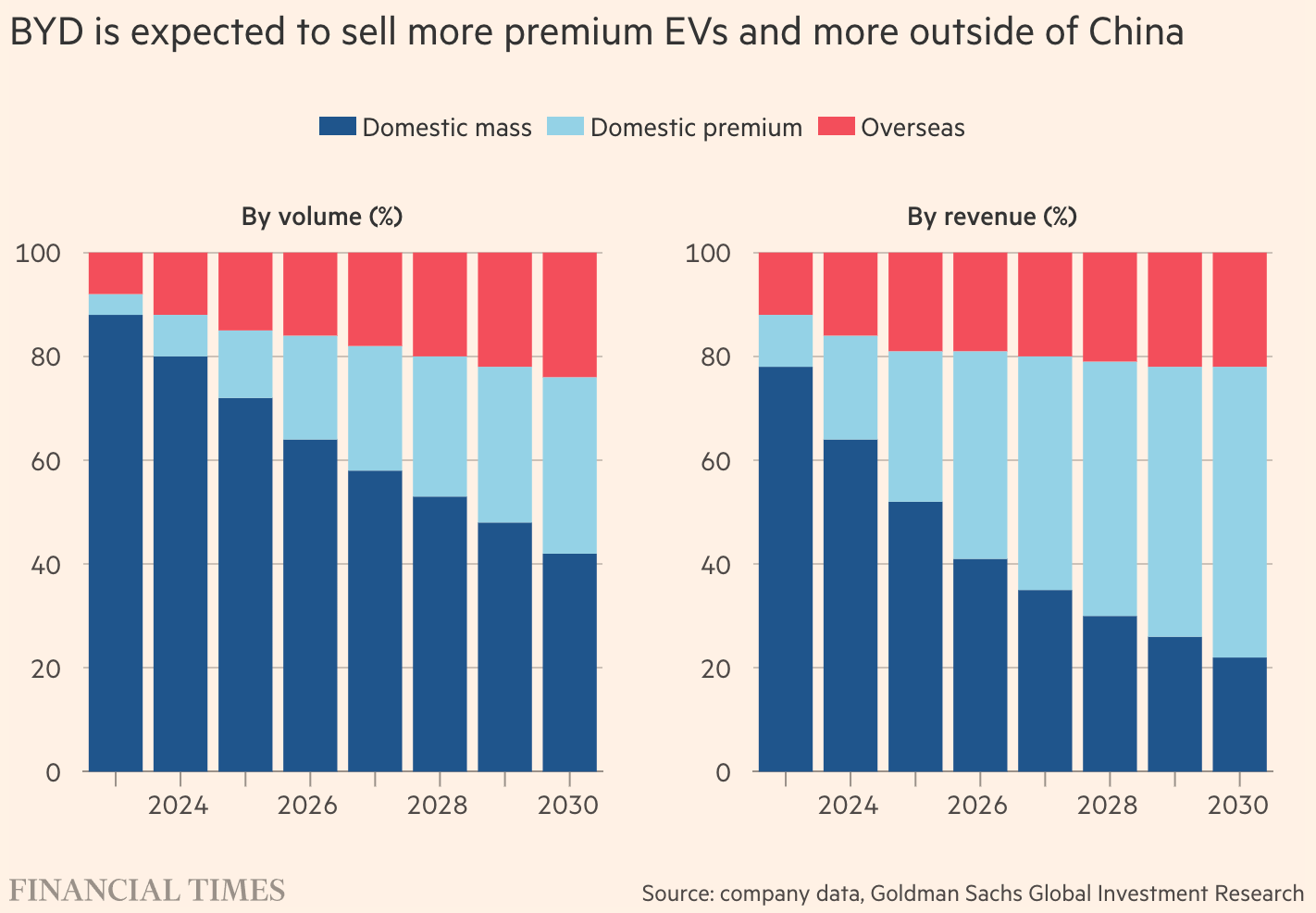

Combined, these efforts have achieved remarkable success. BYD is now the world’s second-biggest electric battery producer, with rapidly growing global sales (White 2024). China is also expanding production in emerging markets, like Brazil (Lakshmi et al. 2024).

Big Picture

A highly capable, coordinated state built up a strategic industrial policy, which wielded the carrot of a humongous consumer market, to extract foreign technology, which it then adopted, finessed, and successfully exported, thanks to its highly-skilled, globally-competitive workers.

Some scholars doubted whether an authoritarian state could really upgrade and innovate, but China continues to rock those priors…

How might such scholars respond?

Well, they might double down and insist that ‘good institutions’ are necessary to develop technological innovations, which China subsequently extracted. Though this would seem to omit China’s genuine success in building on that expropriated technology.

Now let me add a final Evansy point.

The Cultural Impact of China's Tech Exports

Have you stepped into a BYD car?

I’m no China shill, but I can faithfully report that it is an extremely smooth ride. Back in Tashkent, a factory manager generously took me for a tour. I was suitably wowed - much to my host’s delight! He grinned, as I lavished praised on the shiny new motor.

A week later in Fergana Valley, I spent a day with a fun and relatively affluent Uzbek woman. She too wanted to take me for a spin! Another impressive BYD - her pride and joy!

The Chinese carmaker is actually establishing a factory in Uzbekistan, with hopes of producing 300,000 units a year, anticipating strong demand for affordable luxury.

Right there and then, I realised the overlooked cultural value of exports. Goods and services aren’t just things we truck and trade, they’re also powerful signals of national capabilities.

Back in the 2000s, when I lived in Zambia, Chinese goods were generally seen as ‘cheap’ (with questionable longevity..). But as ‘made in China’ increasingly becomes associated with high quality status goods, then global consumers may come to revise their priors, giving China far greater respect and prestige.

So that’s a little sample! Here’s the full table of contents for my forthcoming book,

Great article!

It's fascinating to observe that many large countries have implemented "technology transfer for market access" strategies, yet the outcomes have been quite varied. This strategy is working really well for China in industries like EVs as you described, but in other countries they do the same strategy with worse implementation.

Take India, for instance, during the License Raj era. The government required foreign companies to form joint ventures with Indian firms as a prerequisite for operating in the country. These partnerships often included technology transfer clauses, as seen in the automotive industry where Japanese companies like Suzuki shared their technology with Indian partners. This led to the growth of India’s domestic automotive sector. However, Indian cars have yet to achieve significant international competitiveness.

Similarly, Brazil applied technology transfer conditions in its automotive industry. The government mandated that foreign automakers partner with local companies and share their technology in exchange for market access. Fiat’s involvement is a notable example. Despite these efforts, Brazil has not emerged as a global leader in the automotive industry.

In Indonesia, the aerospace industry has seen partnerships with major players like Airbus and Boeing through IPTN/PT Dirgantara Indonesia. While the industry exists and continues to develop, it remains heavily subsidized and struggles to achieve greater competitiveness. Nonetheless, Indonesia's commitment to pursuing this strategy is commendable!

On the other hand, this approach has been more successful in Japan and South Korea. Japan’s partnerships, such as GM with Isuzu and IBM with Fujitsu, have greatly contributed to its technological advancement. In South Korea, Ford’s collaboration with Hyundai and the partnership between Japanese Sanyo and Samsung are prime examples of successful technology transfer leading to global competitiveness.

I guess this goes back to your point about Size, positioning, and state capacity mattering as well though!

I would like to propose some counter arguments.

1) An EV is just a smartphone on wheels. The majority of smartphone manufacturing had been outsourced to China prior to the EV boom. Additionally all of the top ten battery manufacturers were also located in East Asia. Even without government support, China would have always played a role in the development of electric vehicles.

2) Even though global shipping costs have been falling for over a century, cars are still too heavy for a globalised supply chain. Hence, car manufacturers prefer to set up local manufacturing hubs close to big consumer markets (assuming the host country is stable and has some prior manufacturing expertise). Even without government tariffs foreign car manufacturers would have tried to make cars in China. They might have been partnered with local firms since by the 2000s China had a formidable manufacturing sector.

3) China of the late 2000s didn't have a massive footprint in ICE manufacturing unlike the West, Japan and Korea. China's oil industry is also much smaller compared to its electronics industry. Hence the politics happened to be in their favour.

4) China's success in manufacturing isn't driven by centralised top down control but by decentralised dynamic decision making at the local and provincial level. That's why India can't pull of something like this because they would just doubled down in their "enlightened national leader" belief. Ideally this type of industrial strategy can be done by medium sized countries like Thailand and Vietnam.

5) One also look the failure of China's semiconductor industry to show that Chinese policy making isn't all that it's cracked up to be. China had been trying to get into semiconductor fabrication before Taiwan got into the industry. However despite decades of government support China still only manufacturers trailing edge chips at best. Taiwan, on the other hand, only gave some start-up capital to TSMC and some other firms and privatised them soon afterwards. TSMC surpassed China within 5 years and surpassed the rest of the world in 15 years.

6) I would like to also remind people that China is the poorest majority Chinese country. China would have done much better if they were ruled by pro business rulers like the KMT and not communists.

7) If you look at various tests for intelligence like IQ and/or the PISA score, East Asia always ranks the highest. This has been true for decades. You can attribute this to culture and/or genes, I'm not here to debate that. However, it's just interesting that despite having lower cognitive ability America is much richer than China. This, imo, makes America's institutions to be of greater quality than China's.