Obedience to Mothers-in-Law. Insights from Central Asia

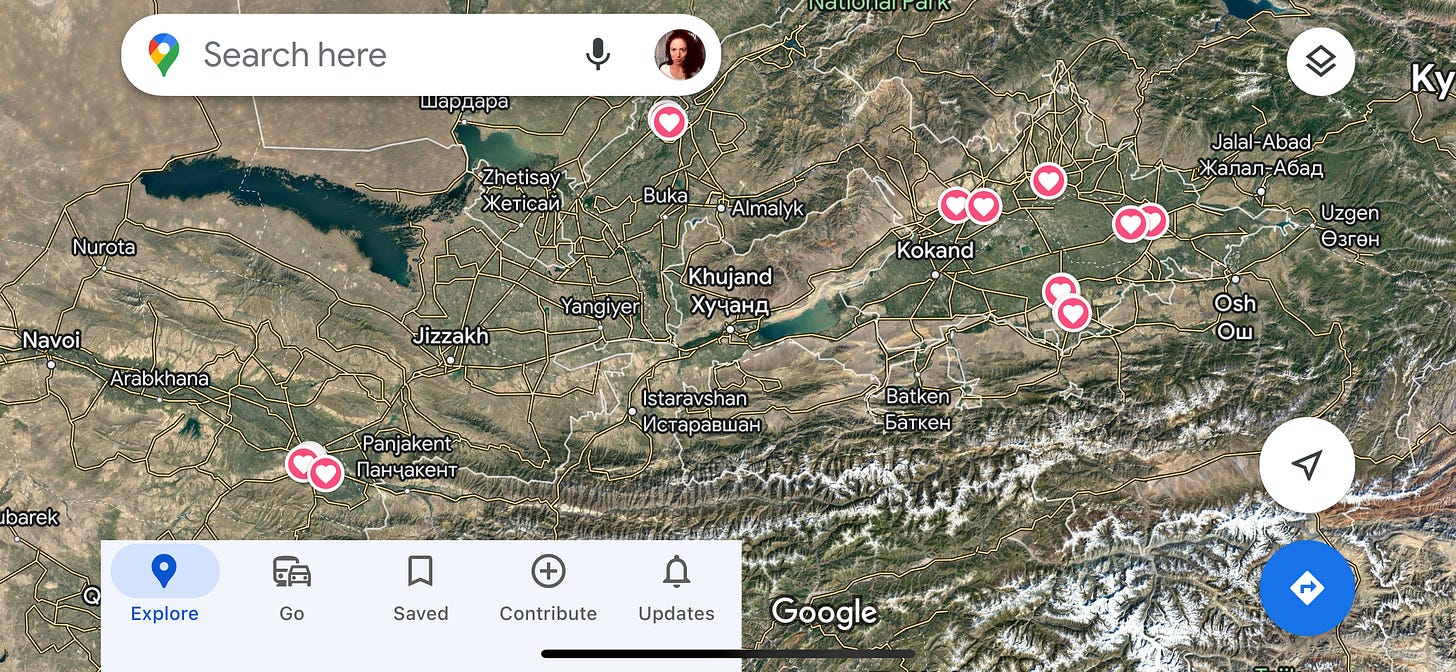

I have just returned from qualitative research across Uzbekistan - travelling to Tashkent, Namangan, Sang, Pop, Margilan, Fergana, Andijan, Altinkul, Samarkand and Tayloq - where I interviewed farmers, traders, waitresses, factory workers, teachers, librarians, housewives, office workers, company directors, students, academics, journalists, lawyers, activists, and government bureaucrats.

This was only possible thanks to incredible Uzbek hospitality, facilitating introductions and translation.

40% of Uzbek women are in the labour force. That’s a little below the global average of 53%. It’s similar to Mexico, not super low. What was really striking - from a globally comparative perspective - was the dearth of feminist consciousness.

Compare activities on 8th March 2023, International Women’s Day. In Uzbekistan, the President congratulated the women and presented state awards. By contrast, in Mexico, thousands marched to demand rights and respect.

In a recent attitudinal survey of rural Uzbekistan, almost everyone said that women should obey their husbands. That’s entirely consistent with my qualitative interviews. Even university lecturers in Tashkent said that questioning their in-laws was ‘rude’ and ‘disrespectful’.

Why is this?

Why are mothers-in-law especially controlling in MENA and Asia?

Uzbekistan is not unique. In North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, many scholars have analysed oppressive mothers-in-law.

In India, Deepa Narayan suggests the primary cause is socialisation. ‘Good girls’ are quiet and obliging. They please others and prioritise family. Anukriti and colleagues’ analysis of Uttar Pradesh reveals that women who live with their mothers'-in-law have less mobility, fewer friends and less control over their fertility. Fatima Mernissi detailed that Moroccan mothers may maintain their sons’ loyalty by discouraging conjugal romance. In Palestine, Cheryl Rubenburg emphasises fear of gossip and ostracism. Openly complaining about family problems is seen as shameful.

Check out my podcast with Anukriti on mothers-in-law.

Socialisation and social policing are all likely factors, I agree.

But why are they so geared up to perpetuate abusive mothers-in-law in these particular geographies? What explains the global-historical variation of inter-female oppression?

Well, I have a new theory!

First, let me suggest 3 key drivers of patriarchal persistence in Central Asia. Then, in a subsequent Substack, I will share how I have revised my global theory of gender.

The Patrilocal Trap

My big new original insight is as follows, echoing Hirschman.

Central Asians traditionally arranged marriages to consolidate dense networks of social cooperation. Uzbeks and Tajiks were patrilocal endogamous, Kazaks and Kyrgz were patrilocal exogamous. Girls married into a man’s family, under their authority. Divorce was socially humiliating, shaming her family. To preserve their reputations and social networks, families socialised their daughters to obey. Even if beaten, she would be encouraged to ‘be patient’. She could not credibly threaten exit.

Patrilocal social cooperation gave men’s families the upper hand. Mothers-in-law could assert their preferences - whether this was to exploit labour or enforce seclusion. Daughters-in-law were caught in what I call “The Patrilocal Trap”.

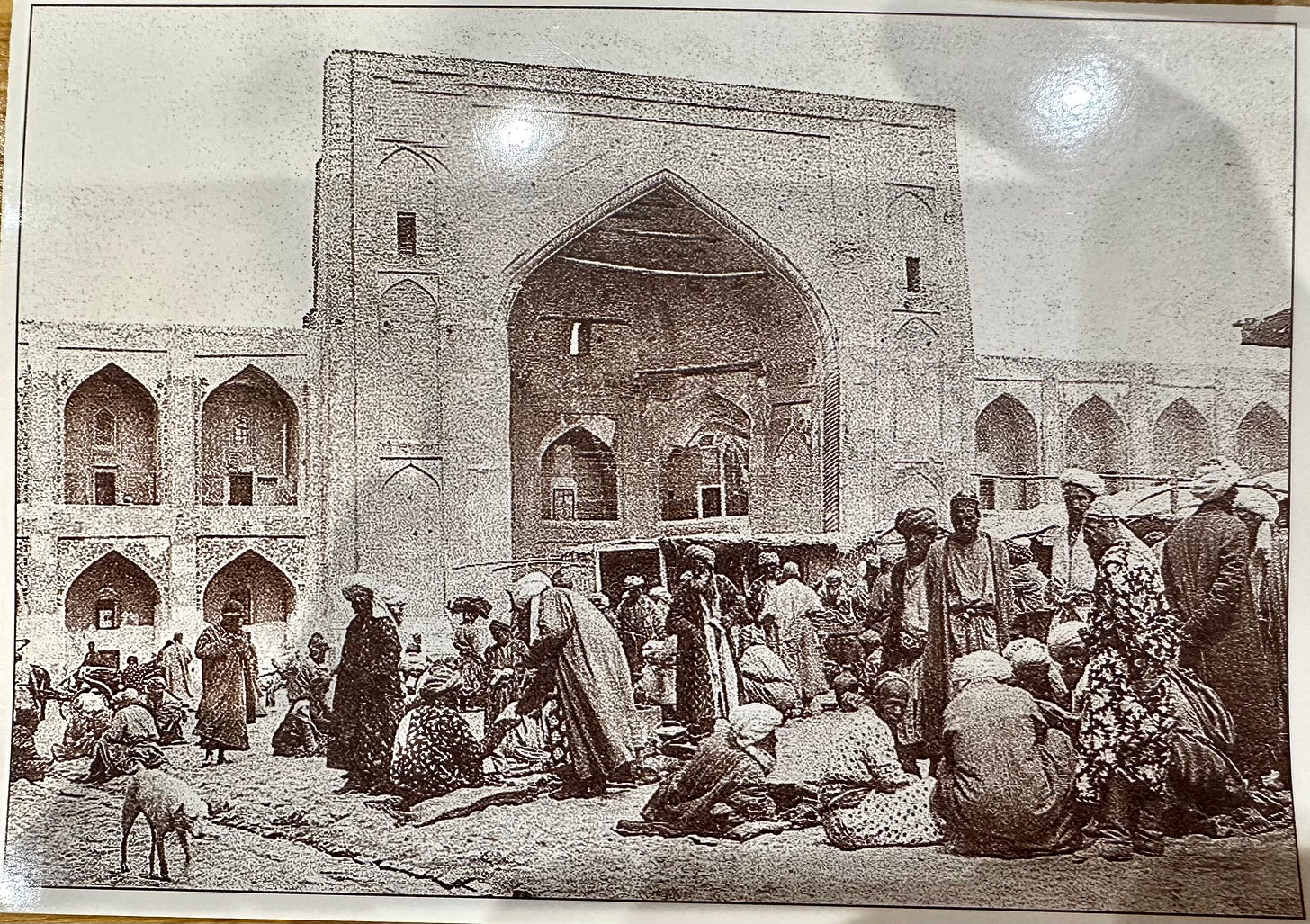

All Central Asians were patrilocal, but there was important variation. Nomadic pastoralists maintained Turkic culture, while sedentary communities adopted Arab-Islamic ideals of female seclusion.

The Soviet dictatorship brought women into public life by forcing them to farm cotton and remove the paranji. But divorce remains stigmatised. Men’s families can still enforce obedience.

The Honour-Income Trade Off

Patriarchy is especially resilient in low- and middle-income economies due to widespread precarity and a scarcity of skilled jobs.

First, financial insecurity reinforces tight-knit kinship. Families secure inclusion in vital networks by preserving their reputations and policing their relatives.

Second, in low- and middle-income economies most jobs are low-skilled. They are tough, tedious and poorly paid. Women only work at a bazaar or factory due to economic desperation. In conservative cities like Namangan, this signals her husband’s shameful failure to provide. It also forfeits her domestic labour (which is vital for hospitality and social cooperation). Available wages are thus too low to compensate for cultural preferences for housewives.

The dearth of culturally esteemed, psychologically rewarding and high-paying careers thus suppresses women’s labour market commitment - as theorised by Nobel prize-winner Claudia Goldin.

A weak labour market also weakens women’s capacity to credibly threaten exit.

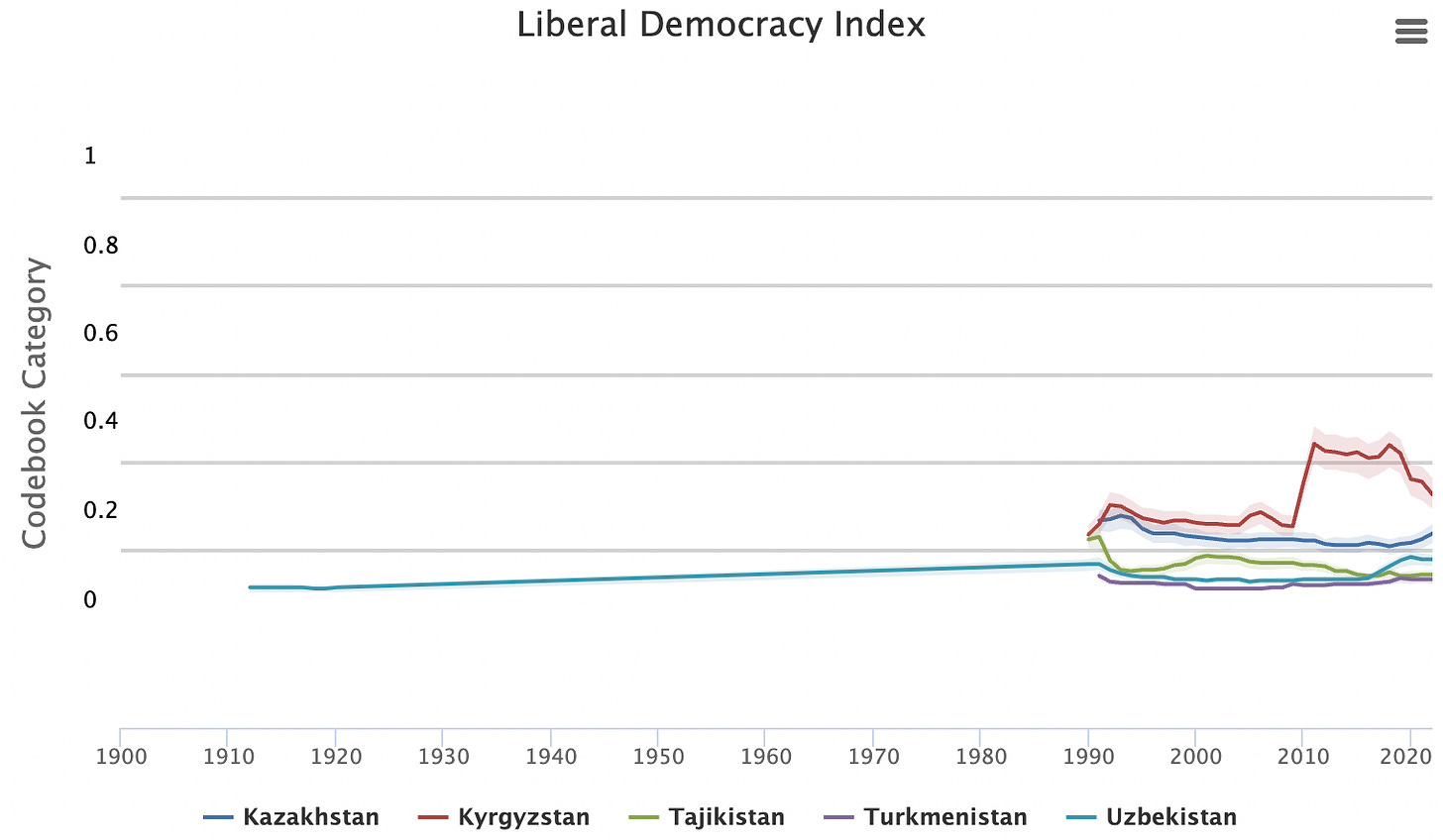

Political Repression

Central Asia is one of the most authoritarian places in the world. Under the Soviet Union, their grandparents were conscripted into wars and forced to harvest cotton. In the post-Soviet era, political opponents have been boiled alive. Critical bloggers are still harassed, arrested and imprisoned.

A century of dictatorships has suppressed resistance, instilling self-censorship and conformism.

Central Asia’s cultural sphere is also authoritarian. Every year, around a million Uzebeks, Tajiks and Kyrgz migrate to Russia. Others take the Umra or Hajj pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia. Whether it’s for work or piety, they are travelling to dictatorships. Migrants rarely return with stories of successful activism.

Internet access has long been restricted by government, unaffordable data and language. Very few Central Asians speak the languages of liberal democracies in Europe, Latin America and East Asia. Uzbeks who had migrated to Canada or Korea for work or study told me that they then became more open-minded. However, they are a tiny minority.

Beyond a tiny liberal elite, the spirit of resistance is extremely weak. Very few people are pushing back, decrying unfairness, complaining to the government or challenging patriarchal readings of scripture. Most remain in a conservative cultural sphere, hemmed in by repression and social policing

When we visited Uzbek homes in December, many were freezing cold but hardly anyone complained.

“You’ll go to prison!” - exclaimed a former company director, while everyone else awkwardly hushed [translated].

Sustained authoritarianism creates what I call a “Despondency Trap”. If people never see successful resistance, they may think it impossible. Rather than waste time in organising, they keep their heads down. This sustains a negative feedback loop.

Democratisation is a crucial precursor to feminism. It nurtures a spirit of resistance, introducing languages of structural oppression, alongside individual rights and freedoms.

Patriarchy persists

Uzbekistan’s patrilocality, jobless growth and repression have thus entrenched female obedience. Consequently, boys are treasured as future pensions - encouraged to hustle, build networks and stand their ground. Women usually prioritise family (assuming their husbands will always provide financially). Business, government, and religious networks remain overwhelmingly male.

Men are recognised as rightful providers, entitled to jobs. Fraternities trust and support each other, exchanging favours and consolidating strength. They prefer to do business with other men, who they stereotype as more competent. Male-dominated networks are thus self-perpetuating. Unless a woman is extraordinarily tenacious or privileged, she may feel deeply uncomfortable in masculine spaces (given ideals of segregation).

Even if a woman becomes a high-earning professional, her husband’s family may still be controlling and violent - since she cannot credibly threaten exit.

More to come

My research in Central Asia rocked my priors. I have revised my theory of patriarchy in North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. That will be my next post…

Thereafter, I will elaborate with a series of posts on Central Asian patriarchy - spanning male breadwinners, divorce stigma, social policing, female seclusion, religion, jobless growth, political repression, and male-dominated networks.

Stay tuned :-)

In case anyone is curious about my qualitative research methodology, I share it below.

Methodology

My analysis draws on the published literature, a month of qualitative research across Uzbekistan, remote interviews with Kazakhs, as well as interviews with Canadian-based Azerbaijanis and Uzbeks. Some participants already knew me (via social media) and kindly facilitated further introductions. To achieve greater diversity, I recruited male and female research assistants in Tashkent, Namangan, Sang, Pop, Margilan, Fergana, Andijan, Antikyol, Samarkand, and Tayloq.

After a century of dictatorships, it was vital to build trust. Some Uzbeks were already comfortable, they knew my research assistants or my social media. To build rapport, I arrived with customary gifts (two loaves of bread and fruit), greeted in Uzbek and welcomed all questions. This fostered open conversations, putting participants in the driving seat, learning about me as a person. Once they had raised a topic, I asked related questions. When chatting to traders, I offered to make promotional Instagram videos for their shops, with me speaking rudimentary Uzbek. Most wanted to take photos and videos, which they shared on Telegram. Young people (keen to study abroad) were especially eager to meet an academic from England.

Farmers, traders, waitresses, factory workers, teachers, librarians, housewives, office workers, company directors, students, academics, journalists, lawyers, activists, and government bureaucrats all shared their diverse perspectives. This socio-economic, geographic and generational range enabled my comparative analysis. Every evening, I iteratively identified what drives cultural change and persistence.

Group discussions were usually thematic, e.g. women were asked how their lives differed from their mothers, or what they anticipated after marriage. When chatting to individuals, I usually asked them to narrate their life histories. This helped me trace change over time, and what shaped personal trajectories.

Since self-presentations are carefully curated, I triangulated accounts through: observation, interviewing relatives, and comparing what people said in different settings. Conceivably, a person may speak differently versus when alone. To mitigate bias, I shared written summaries of my interviews and analysis with different Uzbeks every single day, and made Instagram videos for Uzbek, Kazakh and Tajik followers, inviting their comments. Open transparency helped me learn, network and build trust. Many participants contacted me repeatedly, providing more insights.

Names have been changed to preserve anonymity.