Kartini: Java's Pioneering Feminist!

Imagine a world where girls are secluded at puberty, denied education, and married off to strangers. Now picture a young woman who dreamt of something different. Meet Raden Adjeng Kartini, a Javanese noblewoman who, at the dawn of the 20th century, pushed to overturn patriarchy.

Just as we study the words of early feminists like Rosa Luxemburg, Huda Sha'arawi, Simone de Beauvoir, and Virginia Woolf, Kartini's writings deserve our attention. Her voice joins this global chorus of women who challenged patriarchy, each in their unique cultural context. After all, she hailed from what would become the world's fourth-largest country, at a pivotal historical moment.

So who was this egalitarian champion? Born in 1879 to a noble family in Mayong, Java, Kartini was the daughter of an unusually progressive Regent. Her father’s position in the colonial administration afforded her rare privileges, including a Dutch-language education until age 12. But at the threshold of womanhood, Kartini was confined to her home – a common practice for noble Javanese girls.

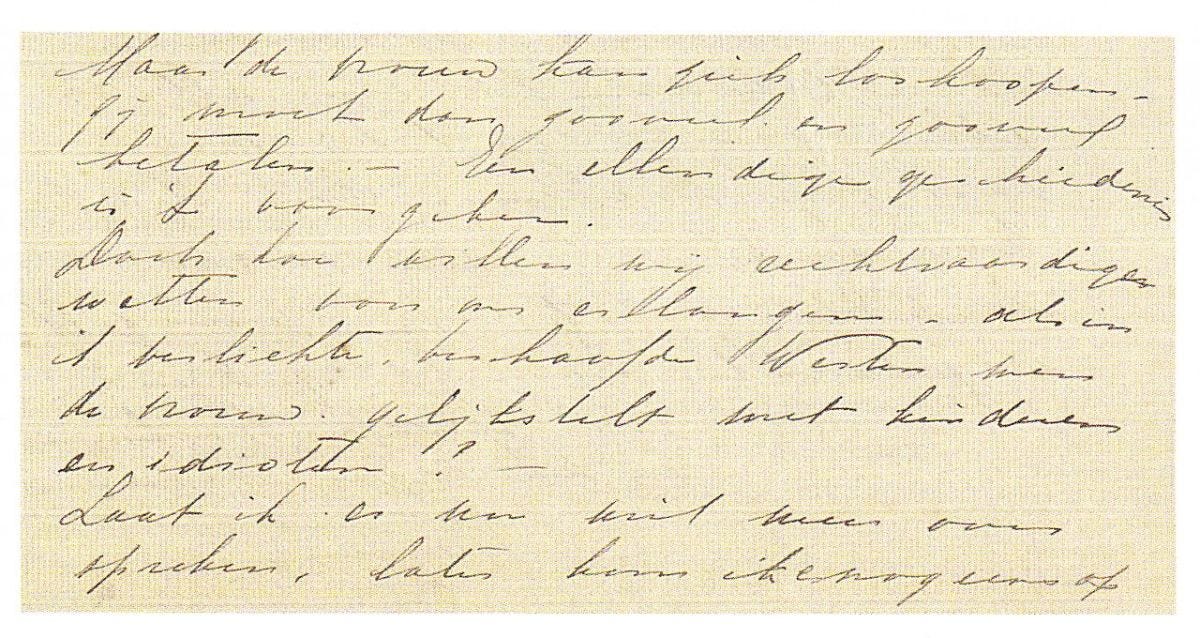

Yet within these confines, Kartini’s mind traversed the world. She devoured books, corresponded with Dutch and Spanish Puerto Rican-born friends, then cultivated progressive ideas. While her views were certainly not representative, they exemplify the cultural contestation of her era. Having pored over 300 pages of her translated writings, I have selected some illustrative excerpts, on the stirrings of Southeast Asian feminism!

Confession: the ending made me cry. Kartini’s story is deeply moving, I share this in awe of her brilliance.

Please note, there are many translations. I am using the version by Agnes Louise Symmers, initially published in 1921.

Kartini does not discuss imperial oppression, but as background let me highlight that peasants were forced to work on cash crops, which exacerbated mortality (due to malnourishment and infectious disease).

Proudly Javanese, integrating European ideas

Kartini saw herself as a bridge between cultures, able to adopt useful Dutch ideas while remaining true to her Javanese identity:

"We came in contact with Europeans very little until a few years ago...

We do not think of Holland as an ideal country, not in the least. Judging from what we have seen of the Hollanders here, we can certainly reckon upon much in that small, cold country that will wound our sensibilities and bitterly grieve us..

The blood, the Javanese blood that flows live and warm through our veins, can never die..

Education and National Development

One of the most prominent themes in Kartini’s letters is her fervent belief in the power of education to uplift Javanese society, particularly women. She repeatedly dreamed of opening a school for Javanese girls to give them skills and expand their horizons:

“Our idea is to open… an institute for the daughters of Native chiefs, where they will be fitted for practical life and will be taught as well the things which elevate the spirit, and ennoble the mind”.

“I should be so glad, so happy, if I could be in a position to lead children’s hearts, to form little characters, to awaken young I minds, to help to mould the women of the future who will be able to carry forward enlightenment like a torch. There is much misery in our Javanese woman's world, there has always been so much suffering, so much bitterness”.

“Our work will have a two-fold aim, first to help to enlighten all our people, and secondly to raise up our sisters, so that they may live and be treated as human beings”

Education would serve the broader cause of Javanese national development:

“We want a free education, to make of the Javanese, above everything, a strong Javanese”.

Segregation

Kartini was secluded from age 12.

“It was a great crime against the customs of our land that we should be taught at all, and especially that we should leave the house every day to go to school. For the custom of our country forbade girls in the strongest manner ever to go outside of the house. We were never allowed to go anywhere, however, save to the school..

When I reached the age of twelve, I was kept at home—I must go into the ‘box’. I was locked up, and cut off from all communication with the outside world, toward which I might never turn again save at the side of a bridegroom, a stranger, an unknown man whom my parents would choose for me, and to whom I should be betrothed without my own knowledge.. My parents were inexorable; I went into my prison. Four long years I spent between thick walls, without once seeing the outside world”.

How I passed through that time, I do not know. I only know that it was terrible”.

Freedom

“At last in my sixteenth year, I saw the outside world again. Thank God! ThankGod! I could leave my prison as a free human being and not chained to an unwelcome bridegroom…

For the first time in our lives we were allowed to leave our native town, and to go to the city where the festivities were held in honour of the occasion. What a great and priceless victory it was! That young girls of our position should show themselves in public was here an unheard-of occurrence. The ‘world’ stood aghast; tongues were set wagging at the unprecedented crime…

But I am far from satisfied. I would go still further, always further. I do not desire to go out to feasts, and little frivolous amusements. That has never been the cause of my longing for freedom. I long to be free, to be able to stand alone, to study, not to be subject to any one, and, above all, never, never to be obliged to marry”.

“It is not customary for young girls to go to weddings and sit among the wedding guests, but Mamma graciously gave us her consent”

“I am told that I must modestly (hypocritically) cast down my eyes. I will not do that; I will look men, as well as women, straight in the eyes, not cast down my own before them”.

Global learning

During seclusion, Kartini was permitted to read Dutch books and correspond with Dutch friends. She was eager to travel, to dismantle her own bias:

“I long to go to Holland for many reasons; the first is study, the second is that I want European air to blow upon the few remaining prejudices that still cling to me, so that they may be wholly driven away...”

To mention but one of the persistent little prejudices, I should not be disturbed in the least if I were alone in a room filled with European gentlemen.

But I can think of nothing that could make me under any possible circumstances, receive alone, even one well-born Javanese young man, who was unmarried. I think it is laughable, absurd, idiotic, but it is true. I dare not talk to a strange man without a companion, and even if there were company, I should think it tiresome, and should not feel at my ease.

So you see that in spite of my strong ideas of freedom, I cannot get away from the influence of my native environment, which keeps girls strictly secluded. When the idea has been strongly inculcated that it is not modest to show oneself to strange men's eyes, then it is a hard task to break away from it.

It must not remain always so, that prejudice must go. How else shall we be able to work together with men? And that is part of our plan. One way in which we hope to accomplish much good”.

Hierarchy

Kartini’s letters paint a vivid picture of Javanese hierarchy. One of the most striking examples of this is the practice of creeping. She writes:

“In order to give you a faint idea of the oppressiveness of our etiquette, I shall mention a few examples. A younger brother or sister of mine may not pass me without bowing down to the ground and creeping upon hands and knees.

If a little sister is sitting on a chair, she must instantly slip to the ground and remain with head bowed until I have passed from her sight.

If a younger brother or sister wishes to speak to me, it must only be in high Javanese; and after each sentence that comes from their lips, they must make a sembah; that is, to put both hands together, and bring the thumbs under the nose.

If my brothers and sisters speak to other people about me, they must always use high Javanese in every sentence concerning me, my clothes, my seat at the table, my hands and my feet, and everything that is mine.

They are forbidden to touch my honourable head without my high permission, and they may not do it even then without first making a sembah.

If food stands on the table, they must not touch the tiniest morsel till it has pleased me to partake of that which I would”.

Obedience

A recurring theme in Kartini’s letters is her struggle against deference. She wrote of her journey from unquestioning acceptance to critical thinking:

“It has always been preached to us that it was our duty to belong blindly to our parents..

As a child I did everything mechanically without question, because others around me did the same thing..

We girls must have no ideas, we have but to think that everything is good as we find it, and to say "yes" and "amen" to everything..

Misery is what the women feel, and yet they have no right to complain..

“Young people should be submissive and obey their elders”, was constantly preached to her; and above all, “Girls must be submissive to their older brothers”

Kartini rejected rote learning:

“I would not do things mechanically without knowing the reason. I would not learn any more lessons from the Koran, saying sentences in a strange language, whose meaning I did not understand and which probably my teachers themselves did not understand. “Tell me the meaning and I am willing to learn everything”.

She was particularly critical of the male dominance:

“Young people should be submissive and obey their elders”, was constantly preached to her; and above all, “Girls must be submissive to their older brothers”. But headstrong Ni could not see why this should be. She could not help it, that she should have been born later than her brother; that was no reason why she should be submissive to him”

Father's Concern for Social Approval

Despite his relatively progressive views, Kartini’s father still placed great importance on social respectability. This created tension when Kartini sought to pursue further education:

“There is still something else; Father and my friends are against it, though fortunately not unconditionally. Father objects because I should be the only girl among all those men and boys, such a thing would be unheard of here”

Kartini also understood that her actions would be seen as radical by Javanese society:

“It is a disgrace for a girl not to marry, to remain an unprotected woman... There is no one yet who does it, who dares do it”

Yet she was determined to push boundaries:

“Then it is time that some one should do it”

Kartini also wanted to write publicly, but she feared conservative backlash.

“If I did write upon serious subjects, I should have the whole native world against me; if I became a teacher, the people would not trust their children to me. I should be called crazy. The idea of serving our cause with my pen is so dear to me, and yet picture to yourself a school without children, a teacher without pupils!

But we have not gone as far as that. We must have education first. For that we must first obtain Father's permission, and then we have to present our petition to the Governor General”

Compulsory Marriage

Kartini suggests that marry is both compulsory and unfair:

“The only road which lies open to a Javanese girl, and above all to one of noble birth, is marriage. From far and near we know of the horrible misery of the woman caused by certain Mohammedan institutions that are so easy for the man, but oh, so bitterly hard and miserable for her.

But here there is a suppressed suffering which consumes itself. For she feels herself powerless and defenceless through her ignorance and inexperience.

The old traditions speak. Fatima's bridegroom takes a new wife and she is asked by the prophet what she feels: “Nothing, Father, nothing”, she declared..

The Eastern woman’s heart has not changed. Many think it an honour to tolerate with unmoved countenances the one or more women their husbands have brought home, but do not ask what is hidden behind that iron mask, or what the walls of their dwellings could tell when the eyes of the world are removed. There are so many burning women’s hearts, with poor, innocent, suffering, childlike souls.

And it was the misery that I saw, even in my childish years, that first awakened in me the desire to fight against these time-honoured customs, and substitute justice for old tradition.”

“But we must marry, must, must. Not to marry is the greatest sin which the Mohammedan woman can commit; it is the greatest disgrace which a native girl can bring to her family.

And marriage among us—Miserable is too feeble an expression for it. How can it be otherwise, when the laws have made everything for the man and nothing for the woman? When law and convention both are for the man; when everything is allowed to him?”

“There is no help for it. Some day or other it will come to pass, must come to pass, that I shall have to follow an unknown bridegroom”.

Arranged Marriages

Kartini decried the lack of choice:

“In the Mohammedan world the approval, yes, even the presence of the woman is not necessary at a marriage. Father can come home any day at all and say to me, ‘You are married to so and so’. I must then follow my husband”

“Love! what do we know here of love? How can we love a man whom we have never known? And how could he love us? That in itself would not be possible. Young girls and men must be kept rigidly apart, and are never allowed to meet”.

“In some places it is the custom when the bridal pair meet for the first time for the bride to wash the groom’s feet as a token of submission before she gives him the knee-kiss…

Unfairness

Kartini saw these customs as unjust:

“Everything for the man, and nothing for the woman, is our law and custom..

Women are nothing—women are created for men, for their pleasure; they can do with them as they will”, sounded brutally in her ears, and irritating as the laugh of Satan. Her eyes shot fire, her fists clenched, and she pressed her lips tightly together in impotent distress. “No, No”, cried her fast beating little heart, “We are human just as much as men. Oh, let me learn. Loose my bonds! Only give me the chance, and I will show that I am a human being, a woman just as good as a man.” She writhed and twisted, but the chains were strong and locked tightly around her tender wrists and ankles. She wounded herself, but she did not break them.

If we had been boys, our father could have brought us up to be fine fellows, we hear till we are weary. When it is certainly true that if the same material is in us out of which fine boys could be made, the same trouble could just as easily make fine women of us. Is it only fine men that have been of use hitherto? And are fine women of no value to civilization?

But we Javanese women must first of all be gentle and submissive; we must be as clay which one can mould into any form that he wishes..

Let me, a child of Java, nourished at her breast, who has lived here all her life, assure you that the native women have honest, simple hearts that can feel and suffer as well as the most delicate, sensitive woman's heart in your country. But here there is a suppressed suffering which consumes itself”

Help us to overcome the relentless egoism of man—that demon which for centuries has held the woman lashed, imprisoned, so that accustomed as she is to ill treatment she sees no injustice but submits with stoicism to what seems the “good right” of the man, and an inheritance of sorrow to every woman…

“It is the history of three brown girls, children of the sunny East; born blind, but whose eyes have been opened so that they can see the beautiful, noble things in life. And now, that their eyes have grown accustomed to the light, now that they have learned to love the sun and everything that is in the brilliant world; they are about to have the blinders pressed back against their eyes, and to be plunged into the darkness from which they had come, and in which each and every one of their grandmothers back through the ages had lived…

People are wrong. It is not only the books that have made them rebellious, conditions have done that, conditions that have existed from time immemorial, and which are a curse, a curse—to every one who happens to be born a woman or a girl”.

Polygamy

“The Mohammedan law allows a man to have four wives at the same time. And though it be a thousand times over no sin according to the Mohammedan law and doctrine, I shall for ever call it a sin. I call all things sin which bring misery to a fellow creature. Sin is to cause pain to another, whether man or beast.

And can you imagine what hell-pain a woman must suffer when her husband comes home with another—a rival whom she must recognize as his legal wife? He can torture her to death, mistreat her as he will; if he does not choose to give her back her freedom, then she can whistle to the moon for her rights. Everything for the man, and nothing for the woman, is our law and custom.

Do you understand now the deep aversion I have for marriage? …

How can I respect one who is married and a father, and who, when he has had enough of the mother of his children, brings another woman into his house, and is, according to the Mohammedan law, legally married to her?…

But how can one speak of a harmonious union as our marriage laws are now? I have tried to picture them to you. Must I not for myself, hate the idea of marriage, scorn it, when by it the woman is so cruelly wronged?

Fortunately every Mohammedan has not four wives or more, but every married woman in our world knows that she is not the only one, and that any day the man's fancy can bring a companion home, who will have just as much right to him as she. According to the Mohammedan law she is also his wife”.

Religious Syncretism

Islam spread to Java through trade, so blended with existing Hindu-Buddhist customs, as well as spirit worship. Kartini’s letters reveal religious syncretism. For instance, she was a Muslim, yet simultaneously said:

“I am a child of Buddha, and it is taught that we should eat no animal food”

Kartini also described indigenous Javanese spiritual practices:

“Our land is full of mysticism, of fairy tales, and of legends”

She recounted witnessing a rain-making ceremony that combined several faiths and featured female priestesses:

“This morning we were taking a drive and we witnessed a naive example of native faith. It was out in the fields. Men and animals were uniting in prayer to the All-Highest to bathe the thirsty earth with blessed rain... In the foreground sat the priest and santries, behind the priestesses in white garments and around them hundreds of men, women and children. Sheep, goats, horses and buffaloes were bound to stakes. A priest stood before them and led the service, praying in a loud voice. Most of the people fell in with 'Amin-amin,' in which chorus the bleeting of the sheep was blended”

Pioneering Change

Kartini wanted to build a pathway for wider social change:

“Even though.. I may give way before it is half reached, I shall die gladly, for the path will then have been broken, and I shall have helped to clear the way which leads to freedom and independence for the native woman.

I shall feel a great content because the parents of other girls who wished to become independent would never be able to say “There is no one, not among us, who does that”.

Female independence

Kartini supposed that if women were more economically independent, then they might have greater autonomy. This required not just skills, but also a shift in culture:

“The only escape from such conditions is for the girl herself to learn to be independent…

Teach her a trade, so that she will no longer be powerless when her guardians command her to contract a marriage which will inevitably plunge her and whatever children she may have into misery. The only escape from such conditions is for the girl herself to learn to be independent.

There is no one yet who does it, who dares do it. It is a disgrace for a girl not to marry, to remain an unprotected woman”.

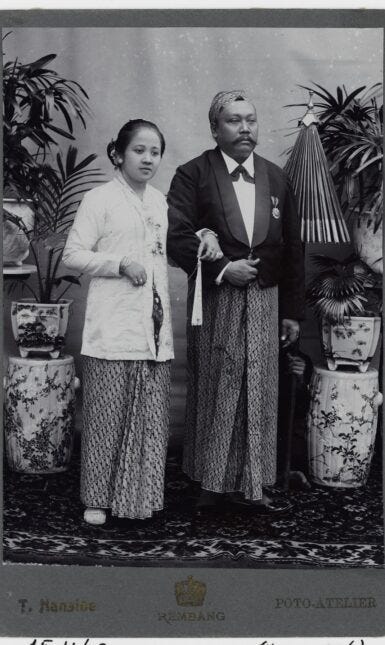

A Happy Ending

Despite her earlier misgivings about marriage, Kartini found an unexpectedly supportive partner in her husband, Raden Adipati Joyodiningrat, the Regent of Rembang. They married in 1903 when Kartini was 24 years old. Contrary to her fears about marriage stifling her ambitions, her union actually provided her with new opportunities to pursue her educational goals.

Kartini wrote enthusiastically about her husband”s support:

“He has promised to stand at my side and support me; it is also his wish and his hope to support me in my efforts to help our people. He himself has already laboured diligently for their welfare for years”

Her husband not only encouraged Kartini's educational aspirations but actively participated in them:

“He too would like to help in the work of education, and though he cannot give personal instruction himself, he can have it done by others. Many of his various relatives are being educated at his expense”

This support extended to Kartini’s plans for establishing schools. Marriage, rather than being an end to her dreams, became a new beginning. She found in her husband a partner who shared her vision for social progress and women’s education. She was supremely happy:

“You do not know with what affection this, my first letter from my new home, is written. A home where, praise God, there is peace and love everywhere, and we are all happy with and through one another”.

Kartini’s genuine surprise to find a loving husband, who truly supported her ambitions, perfectly illustrates my argument that romantic love is a major driver of gender equality, but historically uncommon outside Europe.

Tragic Loss

Kartini died just four days after giving birth to her son in 1904, cutting short her dreams of establishing schools and advancing women’s rights.

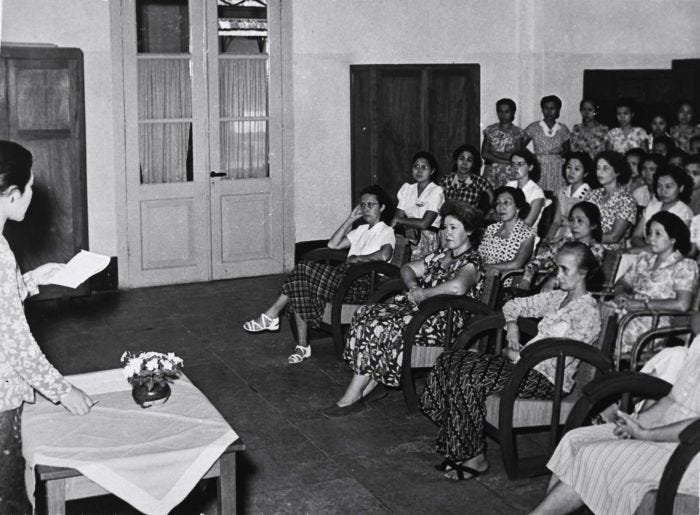

After her death, her letters were published in 1911 under the title “Door Duisternis tot Licht” (Through Darkness to Light). Her advocacy for women’s education inspired the establishment of ‘Kartini Schools’ across Java.

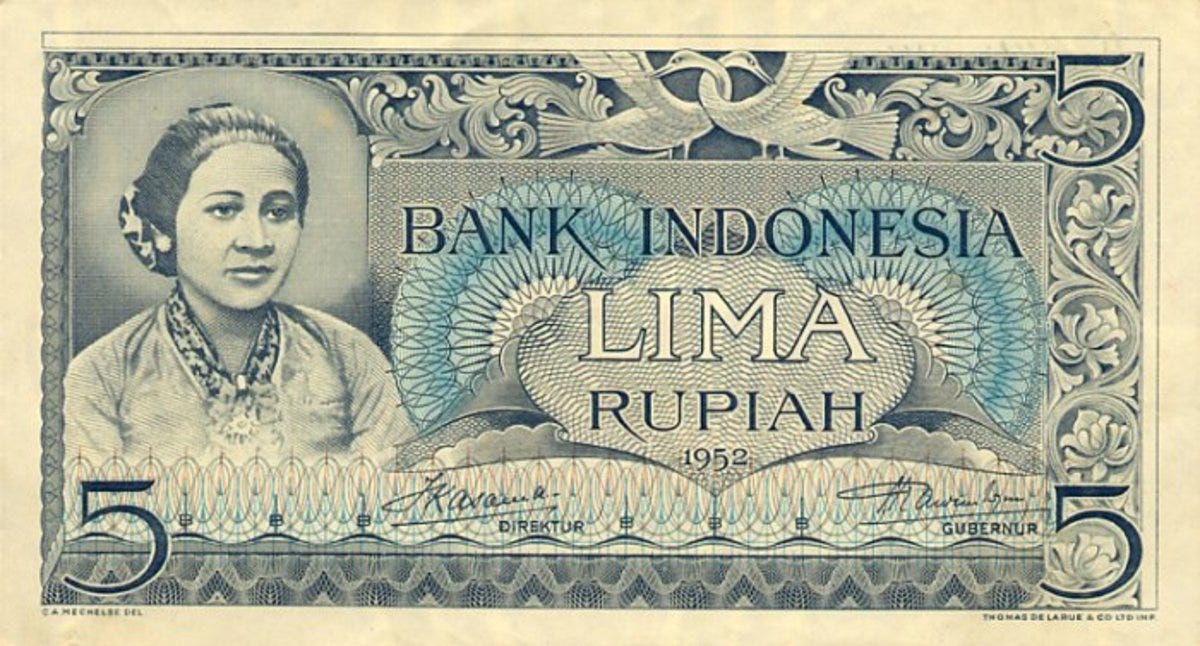

Later, both the Indonesian nationalist movement and feminist organisations drew inspiration from her writings, cementing her status as a National Hero.

Four Reflections:

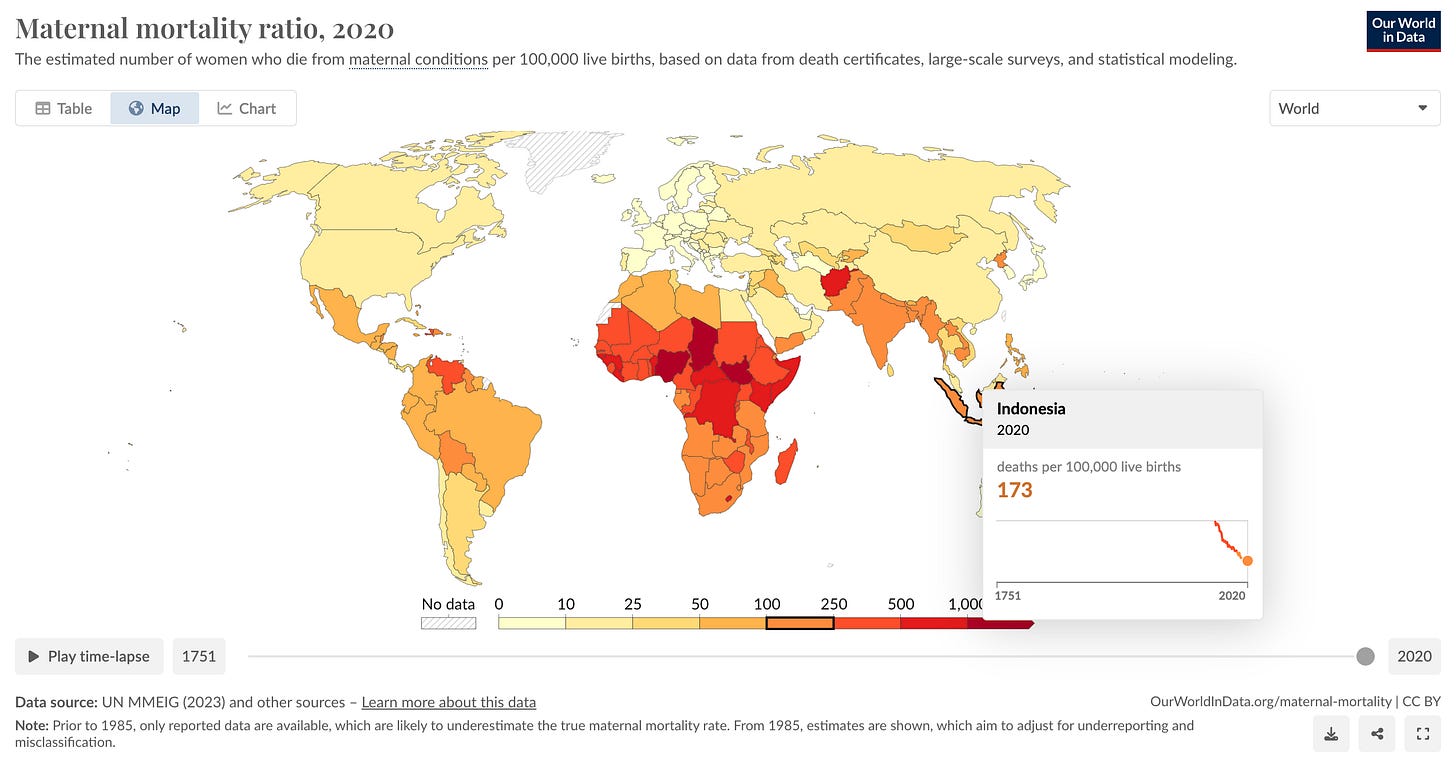

Premature deaths have cut short brilliant minds, worldwide. Kartini was one example, among many others (like the trainee doctor who was tragically raped and murdered in Kolkata last week, as well as Sub-Saharan Africa’s persistently high maternal mortality).

Diverse books (as well as plays, music and films) can help people imagine and pursue alternatives. Media can shift aspirations.

Cultural contestation is a key feature of humanity. Every society includes a mix of conservatives and progressives, who sometimes adopt wider norms uncritically, or merely conform to secure approval, or even campaign to institutionalise ideological dominance. Islamic feminists are much more successful in pluralistic democracies, like Indonesia.

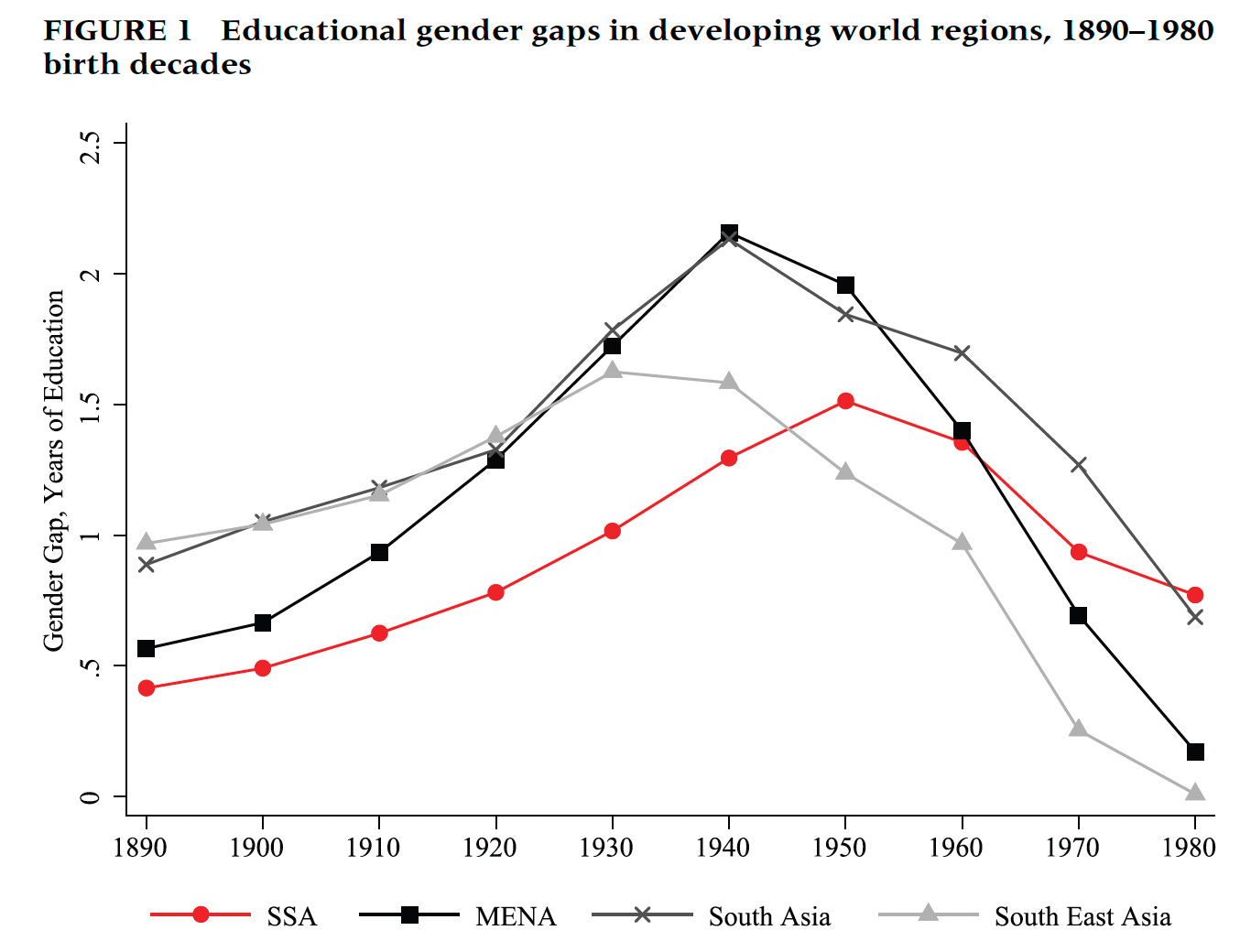

Southeast Asia is also exceptional for its relatively small gender gaps in education. As Javanese men became educated, they increased wanted educated wives and mothers. Since female seclusion was not strongly idealised, girls’ education grew rapidly. Prior culture aided the realisation of Kartini’s vision!

Beautiful. I learn so much from your posts.

Suppose Raden Kartini lived now - in Indonesia or in India. She would go to university and study, she would get a degree. She would probably meet a nice young man and married him. He would also be studying for a degree. They would both start working. They would both be earning money, paying taxes etc. They would feel equal, they would be equals.

Now suppose Kartini's husband got a job offer from the United States and would accept it. He would continue to work in his field, make promotions, be respected, have a career. Raden Kartini however, would be stuck in their home, lonely beyond belief, mopping the floors. Her knowledge would become obsolete, her skills would erode. She would lose her self esteem, being the unwanted additional.

Kartini's life would be over, courtesy of the US government. (Just like mine.)