Greater job flexibility would arguably improve women’s capacity to juggle care and work. I’ve never been entirely convinced. If only women go remote, they may become second-class citizens: cut off from networks, conversations, ideas, trust and camaraderie. My prior is that gender divisions of labour will really be disrupted when men go remote and become engaged fathers.

Was this correct?

Let me present data from several new papers, and you can judge.

The Child Penalty

Child penalties account for a large part of gender gaps in employment, across developed countries. This is shown empirically by Henrik Kleven, Camille Landais & Gabriel Leite-Mariante. After childbirth, women’s earnings plummet.

Claudia Goldin argues that mothers tend to seek more flexible work, and this tends to have lower earnings. College educated fathers, meanwhile, can capitalise on greedy jobs, with long hours and high pay.

Husbands’s job flexibility reduces the child penalty

Minji Bang shows that the motherhood penalty is mediated by husbands’ job flexibility. Chief executives, managers, and surgeons have tight deadlines and need to be available around the clock. But STEM workers can often work remotely and flexibly. If a husband is in an occupation with flexibility, then even after child birth, his partner’s hourly wage remains high!

Okay, but what about selection? Maybe the kind of men who pursue flexible work are inherently more prone to share care? How do we know it’s really about flexibility. What we need, therefore, is an exogenous shock that increases men’s flexibility..

COVID-induced job flexibility for men fostered equality

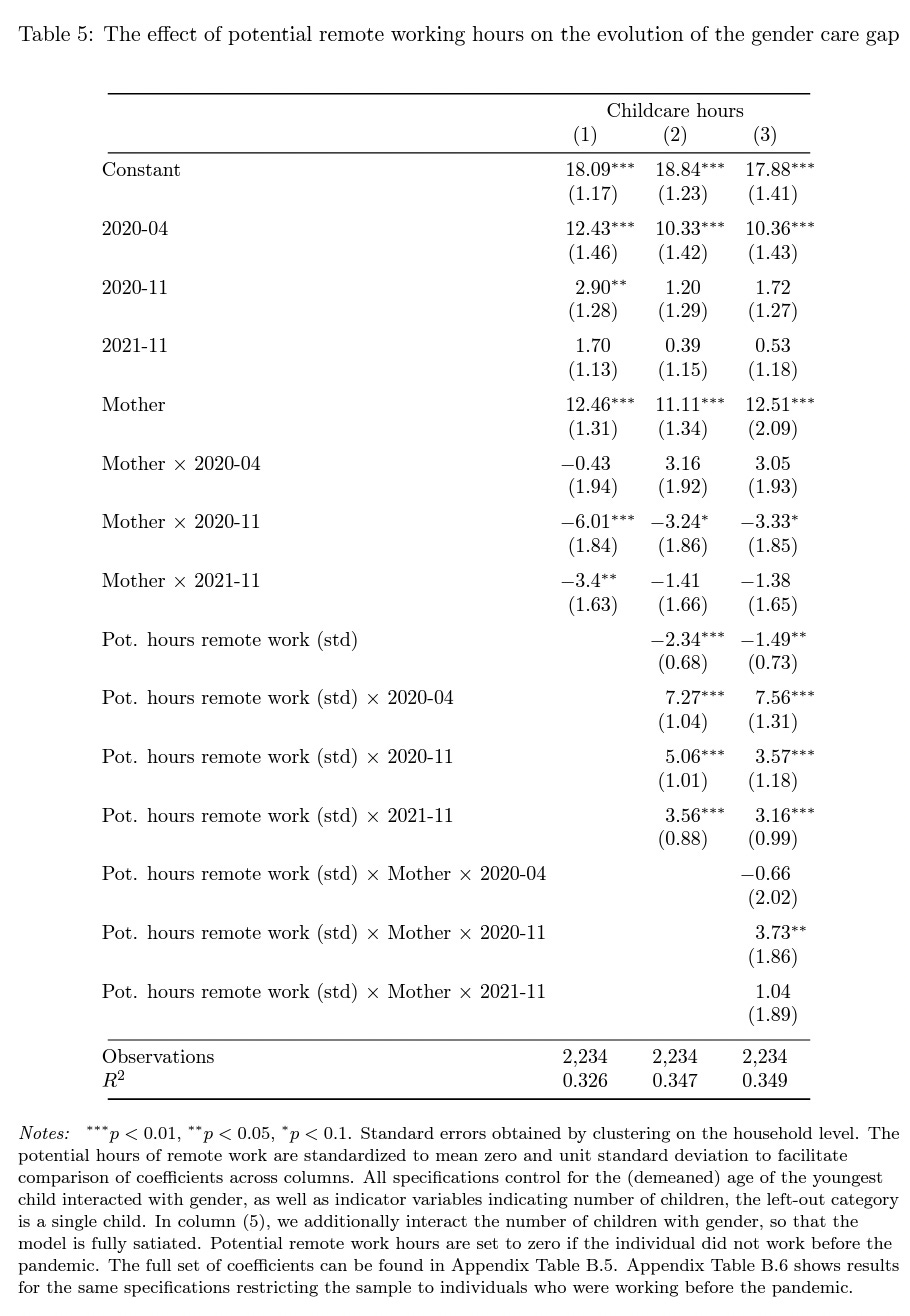

When the Netherlands was hit by COVID, fathers worked more remotely and increased their childcare. Mothers then increased their labour supply.

Over the pandemic, the average gap between fathers and mothers’ childcare provision fell by 27%. This largely occurred amongst households with high potential for remote work.

This comes from a fascinating new paper by Hans-Martin von Gaudecker, Radost Holler, Lenard Simon, Christian Zimpelmann.

The message is clear: men’s job flexibility enables more engaged fatherhood.

Hakim’s preference theory thus seems incorrect. Men’s low share of care work does not necessarily reflect their preferences. When jobs grant greater freedoms, men choose to care for their kids.

What about working class men?

Let me add a point about class, not discussed in the above papers.

Less-educated people are far less likely to have jobs that allow them to work from home. Blue collar jobs in warehouses, retail distribution, factories, construction or transport always takes place far away.

Thus while married graduates are increasingly harnessing technology and sharing care-giving, this is not possible for working class families.

A Brief History of WFH

Back in the Middle Ages, Europeans tended to work in cottage industries, with small-scale production.

The Industrial Revolution heralded massive disruption. Technologies of mass production called men out to work, generating the ideology of a ‘male breadwinner’. Labour service was common before marriage, but mothers generally stayed close to home. Women spent 60% of their prime years either pregnant or nursing.

20th century contraceptives, skill-biased technological change and rampant job-creation enabled women to work in the public sphere (while still doing the lion’s share of care).

Gender divisions of labour persisted well into the 21st century. Even if men wanted to spend more time with their kids, many remained reluctant due to anticipated disapproval and loss of pay. They were locked into a negative feedback loop.

COVID-19 created an exogenous shock, propelling mass WFH. It became normalised. Sensing wider approval and seizing new technologies, more men work from home and share care.

“The Separate Spheres” augmented by the Industrial Revolution are now closing - but only for college graduates.