Saudi-funded Salafism has gained popularity across Indonesia, potentially reinforcing patriarchy. In a country of 276 million, there is enormous heterogeneity, but four key drivers may be compounding gender inequalities:

Salafist grooms seek devout brides, who stay away from unrelated men. Madrasah-education signals female piety, and is likely rewarded in the marriage market. Urban girls are indeed more likely to attend Islamic madrasahs.

Madrasahs entrench religosity by inciting fears of Hell, while preaching gender segregation and patriarchal leadership. 20% of Indonesian school children are currently enrolled in madrasahs. This may affect personal faith and also norm perceptions (of what others approve or condemn).

Salafists believe that men should keep their distance from unrelated women. Piety is thus performed through socialising, doing business and engaging politically through exclusionary male-dominated networks. So, even as Indonesian women outpace men in tertiary education, they may remain locked out.

Conformity is further encouraged through social condemnation and bullying. Politicians can also attract more votes by institutionalising religosity, entrenching sexist prohibitions and punishments for blasphemy.

Indonesia’s cultural shifts are not just intrinsically important (as the world’s 4th most populous country), they also help us scrutinise wider theories about Islamic revival. The Muslim Brotherhood’s ascent in Egypt has been attributed to frustrated graduates’ economic anxiety. But prosperous Indonesia and Malaysia have similarly embraced Salafism. Comparative analysis reveals a global driver: Saudi-funded Salafism. In Indonesia, this appears to entrench patriarchy.

Comments and critiques by Indonesians (and others) are very welcome.

Indonesia’s Rising Salafism

Indonesia is the world’s largest Muslim-majority country, with a population of 276 million. Under President Suharto’s three decades of authoritarianism, Islam was heavily repressed. Hijabs were banned in schools till 1991. But Indonesians are now free to propagate their faith, communicate online, and benefit from Saudi funding. Capitalising on money, technology and democratisation, religious entrepreneurs have successfully championed Salafism.

“In Indonesia, Salafi ideology has penetrated urban and rural, civil servants and villagers... They see corruption all around them and say that it is only Shariah and restoring a caliphate that will be able to fix society” (Din Wahid, a theologian at Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University).

Young urban Indonesians are especially supportive. According to this faith, there is only one correct version of Islam. Individuals must prove their piety by avoiding corrupting forces, strictly following the Qur’an and hadith, emulating the Prophet and ‘pious ancestors’ (al-salaf al-salih). Deviation is condemned as misguided innovation (kullu bid’a ḍalāla), leading to to Hell (kullu ḍalālat fi’l nār). Mosques preach that men should separate themselves from non-Islamic influences to be ‘saved’.

Arabic is seen to symbolise piety, since it is the language of the holy Qur’an. Indonesian Muslims often name their children in Arabic: sons may be called Ahmad, Muhammad, or Abdullah; while daughters could be named Aisha or Fatima. Dress, names and speech are all Arabising.

Salafists reject gender equality

Gender equality is totally rejected by Salafists - as detailed by Ahmad Bunyan Wahib. When interviewed, Indonesian Salafists vilified Western feminists:

“Mereka adalah perusak tatanan keluarga Islam” (they are Muslim family destroyers).

“Suami adalah pemimpin keluarga” (husband is family leader).

Sexual submission is legitimised in scripture, and commonly heard:

“If a husband calls his wife to his bed and she refuses and causes him to sleep in anger, the angels will curse her till morning”. [Sahih al-Bukhari, Book 59, Hadith 48] (quoted in Riyani 2021).

(To be clear, chastity and wifely obedience are not Salafist innovations. 96% of Indonesian Muslims say that a woman should obey her husband).

Ulamā emphasise veiling as the most important practice women can do to prevent temptation (fitna), in the form of adultery and fornication (zina). Salafi and Tablīghī teachers add that the wives of the Prophet and his companions wore the veil (and reference Q.S. al-Aḥzāb [33]:53, 59 and Q.S. An-Nūr [24]:31). As one woman in Aceh explained, women are seen as seducers and men as dogs (lacking self-control).

“There is a saying. Men’s biggest temptation are women. The biggest temptations are wealth, power and women. Those are men’s biggest temptations.. Women are like bones and men are like… dogs” (quoted by Pirmasari 2021.

Gender segregation is strongly encouraged - especially in mosques and madrasas. At the al-Hasanah mosque (next to a university) in Yogyakarta, one preacher told the brotherhood not to mix with women and non-Muslims. Likewise, at the Saudi-funded Institute for the Study of Islam and Arabic (Lipia), classes are gender segregated.

Salafist women may internalise these ideals:

“The cadari [face-veiled women] … avoid ikhtilāṭ (the mixing of the sexes) in all spaces, khalwat (being alone with a male stranger), shaking men’s hands and other practices that they believe can lead them to sin” (Nisa 2023).

Salafists proselytise to purify their communities

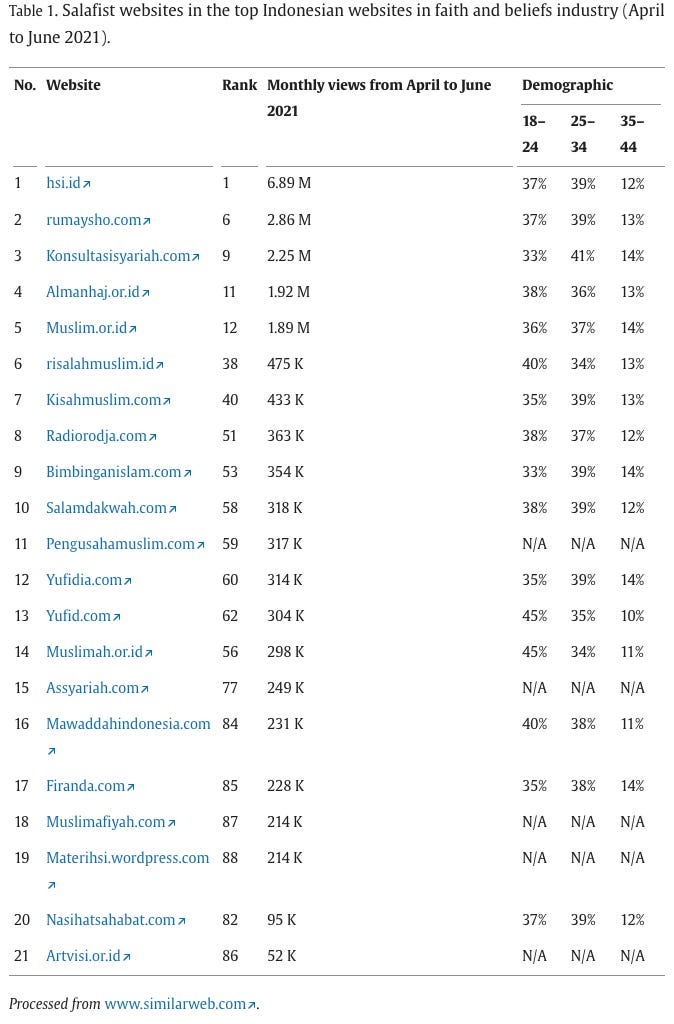

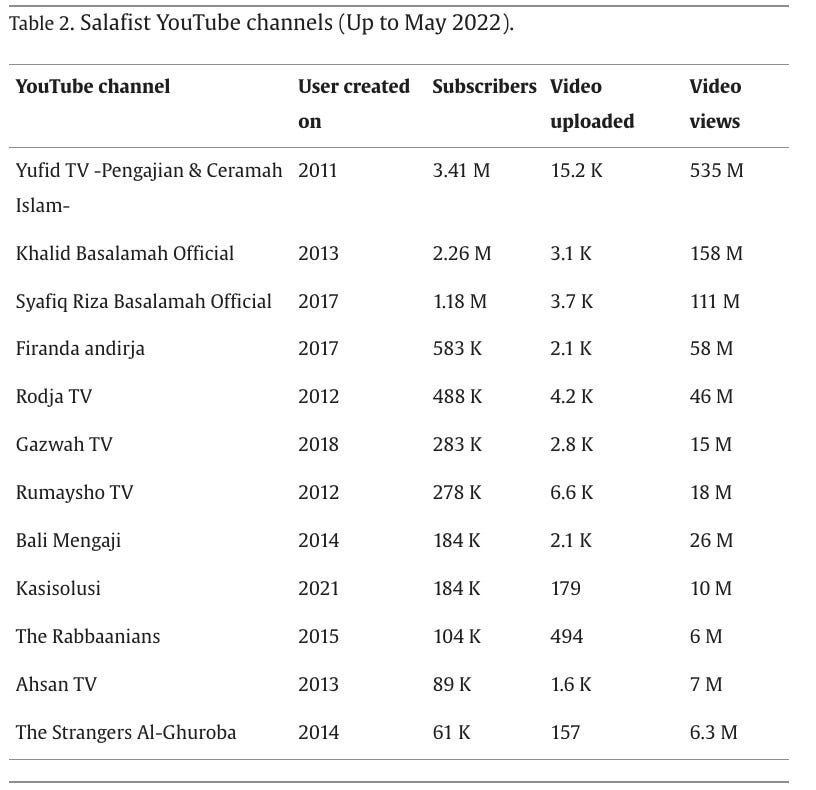

Da’wa (propagation) is seen by Salafiasts as Fard al-ain (an individual obligation). Community radio (like Radio Rodja), as well as online media platforms (like Instagram and YouTube), are used to promote Salafism. Prominent websites attract thousands of video uploads and millions of viewers.

Salafists seek to enforce and institutionalise the correct interpretation of Islam, while purging deviation. Accusations of blasphemy have reportedly increased over time - peaking in East Java (34), West Java (25), and Jakarta (24). Minorities’ places of worship have sometimes been destroyed.

Sharia law is enforced in Aceh. Alcohol, gambling and extra marital sex are all impermissible. After 9pm, women are forbidden from visiting restaurants unless they are accompanied by their husband or male relative. It is also illegal for Muslim women to wear tight clothing. Violations of Sharia law are reportedly punished with imprisonment or public caning. A few years ago in West Aceh, a woman convicted of adultery was flogged 100 times.

In Aceh, government posters instruct mature girls to cover their bodies (save face and hands), wear long veils covering their chests, as well as socks, and soundless heels. Desy Ayu Pirmasari further details that shari’a police conduct ‘Islamic attire raids’.

Community defence of local law (qanun) is seen as pious, explains Pirmasari. This encourages collective enforcement. The man shown below wears a t-shirt asking women to cover their ‘aurat’, so that men can protect their gaze.

As Salafism gains broader popularity, Indonesian politicians gain legitimacy by institutionalising religious prohibitions. At least 30 local regulations now restrict activities by religious minorities, like Shia and Ahmadi Muslims. 120 local regulations mandate the hijab. Two years ago, the Indonesian parliament (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat) voted unanimously to expand the punishments for blasphemy. Anyone who publicly incites others to leave their religion or professes no religion faces up to five years imprisonment. An ex-Muslim who posted YouTube videos criticising Islam has been sentenced for ten years.

As of July 2022, 150,000 Indonesian schools mandate the hijab. Last year in East Java, one teacher shaved the heads of 14 school girls for not wearing a traditional head-covering under the hijab. In 24 Muslim-majority provinces, girls who refused to wear the hijab were either expelled or left after bullying.

20% of Indonesian school children are enrolled in madrasahs

Indonesia has the fourth largest school system in the world. It also has the world’s largest Islamic education system. 20% of Indonesian school children are enrolled in madrasahs.

Madrasahs offer a more religious curricular in order to appeal to conservatives. Some include secular subjects, others focus entirely on Islamic law, ethics, the Qur’an, traditions of Prophet Muhammad, and Arabic. Madrasa enrolment is correlated with greater piety: praying 5 times a day, fasting during Ramadan, reading the Qur’an, attending Friday prayer, performing Sunna prayers, joining ‘pengajian’ prayer groups, and paying ‘zakat’ (charity).

Curricular vary. In Salafist boarding schools, boys usually study ‘tauhid hakimiyah’: Allah alone is sovereign, and scripture is the only source of moral legitimacy. Madrasahs also cultivate a collective identity and community of believers. Piety is instilled by contrasting ‘us versus them’, ‘loyalty and disloyalty’ (Al Wala’ Wal Bara).

Students also emphasised a feeling of surveillance, of being watched by authorities:

“I always wear the cadar at home during the pesantren [boarding school] break, because I am afraid I might accidently meet ustādhāt [female teachers] or kakak pengurus [seniors]. I do not feel good if they see me without the cadar” (Azizah, a 15-year-old student from Lampung, quoted by Nisa 2023)

Some religious pre-schools prohibit physical activities (like rope climbing, climbing up the steps to a slide) as ‘bid’ah’ (innovation) and ‘haram’ (forbidden), as onlookers might find it sexually arousing. Classic songs (like Balonku and Ular Naga) have been revised to instil fear of Hell.

‘Dragon’ (Ular Naga)

The dragon is amazingly long

Twisting and turning here and there

It’s looking for something tasty to eat

There, the one at the end.

‘Fires of Hell’ (Api Neraka’) (to the same tune)

The fires of hell are amazingly hot

Flames licking here and there

They are seeking naughty children

Who do not do their prayers and read the Qur’an.

Girls are more likely to be enrolled in madrasahs

Across Indonesia, gender gaps in school enrolments have disappeared. But this is partly because girls were increasingly sent to madrasas. Elli Berman and Ara Stepanyan find that,

“more than two thirds of the implied increase in the prevalence of female school attendance between the 1960s and the 1990s can be attributed to increased attendance of Islamic schools”.

Today, rural, poorer and uneducated parents are more likely to send children to madrasahs. But regardless of household income, urban girls are significantly more likely to attend madrasahs, while boys are much more likely to be in non-religious private schools.

M. Niaz Asadullah and Maliki calculate that

‘the total number of girls in senior madrasahs (private as well as public) was twice that of boys’.

What’s driving demand for female piety?

Finances aren’t the answer. Girls are more likely to attend madrasahs irrespective of household income. Urban families are preferentially choosing to send their daughters to madrasahs. The story must be about demand.

In Indonesia, female education is highly responsive to marriage markets. Nava Ashraf, Natalie Bau, Nathan Nunn and Alessandra Voena show that more educated daughters commanded a higher bride price. Men’s preferences clearly affect female education. Now, if men become more religious, we might expect to affect their idealised brides.

To recall, Salafist men condemn gender equality, believe that wives should obey their husbands, and insist men and women should keep their distance. Madrasahs that teach girls how to behave piously and mother the next generation of Muslims may provide an excellent signal of piety. This may well be rewarded in the marriage market.

While religious education likely depresses women’s future earnings, not everyone is so materialistic. Salafists believe that our our time on earth is just a testing ground for what really matters (i.e. the afterlife). In response, girls may both internalise and strategically signal religosity - through madrasahs, veiling and segregation.

How might religious education affect gender relations?

With a population of 276 million, there is enormous diversity. We do not have representative data on gendered content, since madrasahs do not upload their content online. Heterogeneity is to be expected, but all published qualitative research suggests that madrasahs encourage wifely submission and gender segregation.

In East Lombok, Ma’had Anjani madrasah teaches that a pious woman prays, upholds moral virtue, and obeys her husband (who has highest status). Gurus also teach that women will go to hell for refusing sex with their husbands, and that a woman who marries a polygnous man will be greatly rewarded in paradise. The curriculum excludes non-religious material. They only learn Islamic ethics, history, law and Arabic. Some local women have criticised these teachings as indoctrinating women into servitude and marital rape.

Farha Abdul Kadir Assegaf (an Indonesian researcher, activist and Muslim) undertook ethnographic work in rural Java, studying a village pesantren (boarding school). Girls and boys are taught apart. Gender segregation is seen as obligation - based on the Qur’an and conduct of the Prophet Muhammed. This prevents ‘ikhtilat’ (close interaction between men and women).

Girls were instructed to become servants of God, perfect housewives, and give birth to as many children as possible. Anyone caught with inappropriate material (like comic books, magazines, Shia Islamic books, or impolite pictures) was ‘brought to trial’.

The pesantren was run by men. Female teachers could provide advice, but typically did so in writing so as to avoid ‘ikhtilat’. This sharply contrasts with single-sex secular schools, which usually provide ample opportunities for female leadership.

But did students really internalise these norms?

Assegaf spent time hanging out in the dormitory. Students often condemned women’s emancipation and accused the West as trying to destroy Islam, via Muslim women. Family planning was vilified as a tool to reduce the Muslim population. And the only reason capitalists champion free association with men is to exploit women’s bodies. One student explained:

“Muslims have taken the West as their qibla [the direction faced when praying, orientation], and the result is, well, complete destruction. … the West and the Jews, as written in the Qur’an, always undermine the lives of the Muslim community. The Islamic community is ruined from within. Beginning by destroying the lives of women, they aim to ruin the next generation of militants”.

Assegaf concludes,

“The general direction for policy in the pesantren has therefore become one that strengthens the position and power of men”

Why aren’t women seizing good jobs?

Economists Schaner and Das are puzzled. Indonesia has achieved rising education and sustained economic growth, yet female labour force participation is stagnant.

Why has the attachment of Indonesian women to the labor force, both in terms of whether they work and what they do, been so stagnant despite decades of sweeping socioeconomic change in Indonesia?

Schaner and Das 2016

Now,Schaner and Das present another conundrum. When they regress log wages on education, urban versus rural residence, and occupation, they still find a large and inexplicable gender wage gap. Qualified women are still earning much less.

They also find that women are significantly under represented in management.

Among entrepreneurs, there are marked gender differences. Men are much more likely to establish small or medium enterprises, while women’s firms are micro, usually only involving herself, without paid workers, run from home, for limited hours.

What on earth could it be going on?

[They do not mention religion]

Piety, paradise and social respectability all depend on the sexes staying apart.

Pious, shy and modest brides are usually sought by Salafist men. Marriage markets would help explain why - irrespective of income - girls are more likely to be educated in madrasahs.

Gender segregation is championed as morally virtuous by Salafist mosques, madrasahs and media platforms.

Labour market inequalities:

Since women’s respectability is contingent on shyness and modesty, they may be reluctant to assertively ‘truck, barter and exchange’.

Men keen to prove their piety may prefer to socialise, do business, and discuss politics with other men. Commercial and political networks are therefore likely to remain male-dominated.

Men who see themselves rightful patriarchs may also feel uncomfortable with female bosses and leaders.

Wifely obedience is preached by Salafists.

So even as women accumulate money, skills, and seniority at work, piety requires they submit at home. Religosity not only constrains female labour supply, it may also inhibit gender equality.

Patriarchal governance:

Over the past twenty years, public support for female leaders has declined. Indonesians are now less likely to want female leaders.

Religious proscriptions are championed.

Deviants are harassed and bullied - encouraging quiet conformity.

Politicians that enforce male guardianship, mandatory hijab and punishments for blasphemy also gain legitimacy.

Punitive authoritarianism then silences dissidents.

The same trends may be occurring worldwide, thanks to Saudi-funded Salafism. Indonesia’s Islamic feminists face an uphill battle.

When I started researching “The Great Gender Divergence”, I stated that the world has become more gender equal. Emerging evidence from Indonesia (the world’s fourth largest country) suggests I was wrong. Since we lack panel data, it’s unclear whether Salafism has merely entrenched or amplified patriarchy.

Going forwards, I will be undertaking two months of qualitative research in Indonesia. Please do get in touch if you’d like to meet.

Comments and critique are always welcome.

Related Posts

Further Reading

“Bride Price and Female Education” by Nava Ashraf, Natalie Bau, Nathan Nunn and Alessandra Voena

“Religion, Education and the State” by Samuel Bazzi, Masyhur Hilmy and Benjamin Marx

“Face-veiled Women in Contemporary Indonesia” by Eva F. Nisa

“Indonesia: Submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child

“Islam, Women's Sexuality and Patriarchy in Indonesia: Silent Desire” by Irma Riyani

“Being Pious Among Indonesian Salafists” by Ahmad Bunyan Wahib

Great post!

3.5% of the world's population but very little is written in the West about Indonesia.

I have a couple of questions:

- How effective do you think is religious education in Indonesia? Judging by the Spanish experience (*) I'm a bit skeptical of the effect that madrasahs have on piousness and religiosity.

- Do you have any ideas on why Aceh is more religious than the rest of Indonesia? It would seem the rest of Indonesia is actually catching up with Aceh, but I don't know of any good explanation for why islamisation would have happened earlier in Aceh.

My naive explanation would be that historically Aceh had more contact with the big Islamic centers in Arabia and Muslim India, being close to the route that Muslim traders traveled on their way to Eastern Asia. But I don't find it very convincing.

(*) More than 30% of education in Spain is private, and most private schools are religious.