How Courtship Transformed Masculinity

Female Choice, Male Competition, and the Secrets to Gender Equality

Ask an economist what drives progress towards gender equality, they’ll probably emphasise sustained economic growth, contraceptives, and female employment. Talk to a political scientist, hear that it’s all about feminist activism. All valid, but I want to add a culture of female choice, male competition, and marital companionship.

While romantic love is experienced worldwide, there is enormous variation in the extent to which it is celebrated or suppressed. In regions where marriages are arranged by kin or coerced through brutal violence, her wants and welfare count for little. If divorce is stigmatised, she cannot credibly threaten exit and must then endure any abuse.

But where men must compete for a woman’s hand, they must demonstrate devotion and emotional companionship. A man who cherishes his wife tries to make her happy, supporting her ambitions and sharing the washing up.

What follows is a speech I performed at my German friends’ wedding: two thousand years of history through the lens of marriage, starting with Ancient Rome to the Reformation, Wars of Religion and subsequent Romanticism, all the way to 1970s counter-cultural liberalisation.

To keep it vaguely romantic, I have omitted some parts of German history.

Classical Inheritance: Marital Monogamy

Male citizens of Athens and Rome were only permitted one legal wife. Preventing polygamous hoarding gave every free man the opportunity to get a wife, sire children and pass on property. Egalitarianism among male citizens may have aided fraternal camaraderie and state legitimacy.

Importantly, however, normative monogamy is not sufficient for female choice nor male competition. Daughters’ marriages were still arranged by families, while elites could procure infinite concubines - via slavery. Only with the demise of labour coercion did Europe achieve de facto monogamy.

In the early Middle Ages, the Catholic Church began enforcing a dramatic transformation of marital norms. They banned cousin marriage, which eroded clan-based kinship in Western Europe; and they required consent from both the bride and groom, which undercut arranged marriage outside the aristocracy. The wedding ring was placed on the fourth finger - a direct line to the heart, representing their unity. The Church also transformed marriage into a sacrament - a profound union, considered equal to baptism or communion.

Economic shifts encouraged a shift towards male competition and companionate marriage. By the 15th century, serfdom had disappeared in north-western Europe, replaced by wage-labour markets. Young men and women often left home to work on farms, workshops, and manor houses. In Württemberg, most women in their late teens and early twenties did not spend their days supervised by kin - they were workers. Mixing, mingling, flirting and listening to gossip, single women could assess potential matches. Just like any functioning market, men had to compete. Oafs, thugs, paupers and bores might well remain single.

Couples then established separate households, away from extended kin. This privacy and mutual dependence permitted greater emotional intimacy.

Yet Catholic theologians’ highest ideal was actually celibacy. Marriage was not framed as a site of mutual fulfilment, but rather a concession to human weakness, a remedy for sin. Sex, even within marriage, was marred with suspicion, tarred with lust and loss of self-control after the Fall. Meanwhile, misogynist proverbs ran rampant:

The Reformation: Marriage as Companionship

Protestant Reformers got lucky: their theological movement coincided with printing technology, university networks, political fragmentation. Luther’s pamphlets sold like wildfire, racing through personal networks, while universities became hotbeds of radicalisation, turning students into fervent reformers!

Protestants praised marriage based mutual affection and companionship. This catalysed an explosion of marriage sermons, household manuals, and advice literature - urging husbands to rule wisely, love their wives, govern gently and cultivate mutual affection. English Puritan Robert Cleaver (d.1613) wrote,

“The husband is not to command his wife in manner, as the Master his servant, but as the soul doth the body, as being conjoined in like affection and good will; just as the soul in governing the body tendeth to the benefit and commodity of the same, so ought the dominion and commandment of the husband over his wife . . . tend to rejoice and content her”

A wife should be emotionally mature and financially able to support a household - at least over the age of 20. And as for sex, Protestants condemned prostitution and raided brothels, but regarded sex within marriage as entirely legit! Together, these forces - monogamy, consent, ideals of mutual respect, and wage work among youth - incrementally pushed marriage toward female choice, male competition, and emotional companionship. Neil Cummins’s research on English wills reveals this shift – from the 17th century, men increasingly referred to their wives with affection.

Small print: Germany was by no means a feminist utopia. Guilds were the ultimate frat club, which locked women out. Every institution, every mode of power and persuasion was dominated by men. In religiously-contested territories, rivals struggled to demonstrate their superior power to catch and snare Satan’s agents. Areas with intense wars of religion saw more witchcraft trials: vanquishing the devil.

Towards Liberty!

From the sixteenth to the seventeenth century, Europe was torn apart by religious wars. Convinced by their claims to absolute truth, salvation and authority, Protestants and Catholics sought to entrench their dominance and persecute heretics. Europe’s zealots were on the rampage - razing towns, torturing suspects. God’s war proved immensely destructive.

Exhausted by generations of bloodshed and disillusioned by imposed orthodoxy, European philosophers began to question whether beliefs could, or should be coerced. Protestantism had already encouraged ‘sola scriptura’ - knowing God by reading the Bible. Now, this principle was applied more broadly, emphasising individual conscience.

In England, John Locke (1689) pushed for religious tolerance, arguing that since people’s personal beliefs cannot be changed by force, and spiritual beliefs are private, then coercion only breeds hypocrisy and violence. English people increasingly accepted that people could differ - in beliefs, ideas and expression - and this was fine.

Simultaneously in German lands, theologians like Philipp Spener were advancing a similar transformation. Pietists used believers to cultivate inner faith, rather than outward conformity. True Christianity was not about dogma, but heartfelt sincerity and inward conviction.

Meanwhile, the print industry was booming! Pamphlets, newspapers, and cheap prints circulated across Europe, while coffee houses and debaucherous inns became lively hubs of discussion, stocked with opinionated newspapers and biting satire that savaged the airs and graces of the nobility. Elites were kicked off their pedestals and disagreement became part of ordinary life.

‘Free speech’ was gaining traction, though more as an aspiration than reality - championed by underdogs, but suffocated by those in power. The French and American Revolutions were part of this wider shift, reflecting men’s growing demands for political, religious, and sexual freedoms.

Romanticism, the Self and Subjectivity

If private sincerity mattered more than external conformity, shouldn’t inner feelings have moral weight? Building on this culture of tolerance, private conscience and debate, European philosophers, poets and artists embraced Romanticism: moral value was no longer defined by the church, crown or custom, but rather the Self!

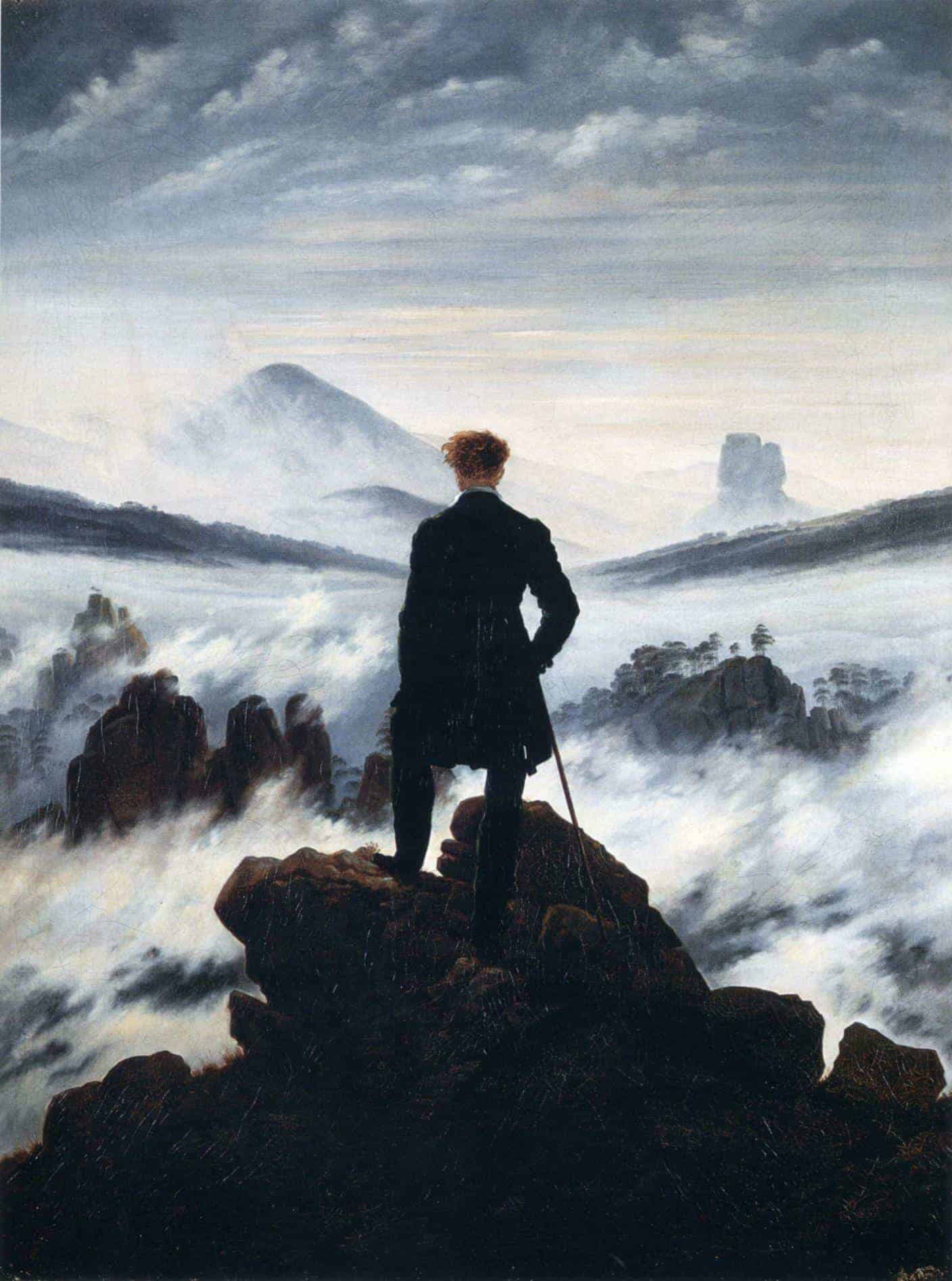

Romanticism elevated subjectivity: a man’s emotions, imagination and longing. Turner’s storms, Goya’s nightmares, and Friedrich’s Lone Wanderer invited viewers to engage emotionally - as if feelings have some moral validity. Value lay not in sacred law, but one’s mind.

This radical culture of the “I” flourished in the small university town of Jena (Germany), where writers and thinkers bucked all kinds of convention - in marriage and philosophy - to pursue emotional authenticity, following their own desires. Freedom was revered as a personal imperative. The sovereign male self - expressive, inward, and restless - became the new template of cultural prestige.

Thanks to expanding print networks, rising literacy, circulating libraries, letters, and salons, this ideal spread with speed and gusto! Young educated men in Leiden, Copenhagen, and Geneva came to see themselves as leading protagonists.

Rewriting the Script!

One of Europe’s most popular novelists of the early 19th century - Johann Wolfgang von Goethe - celebrated not just inner feelings, but love itself. In “The Sorrows of Young Werther”, Werther’s intense longing for Lotte is morally legitimate. The tragedy is not his love, but societal constraints.

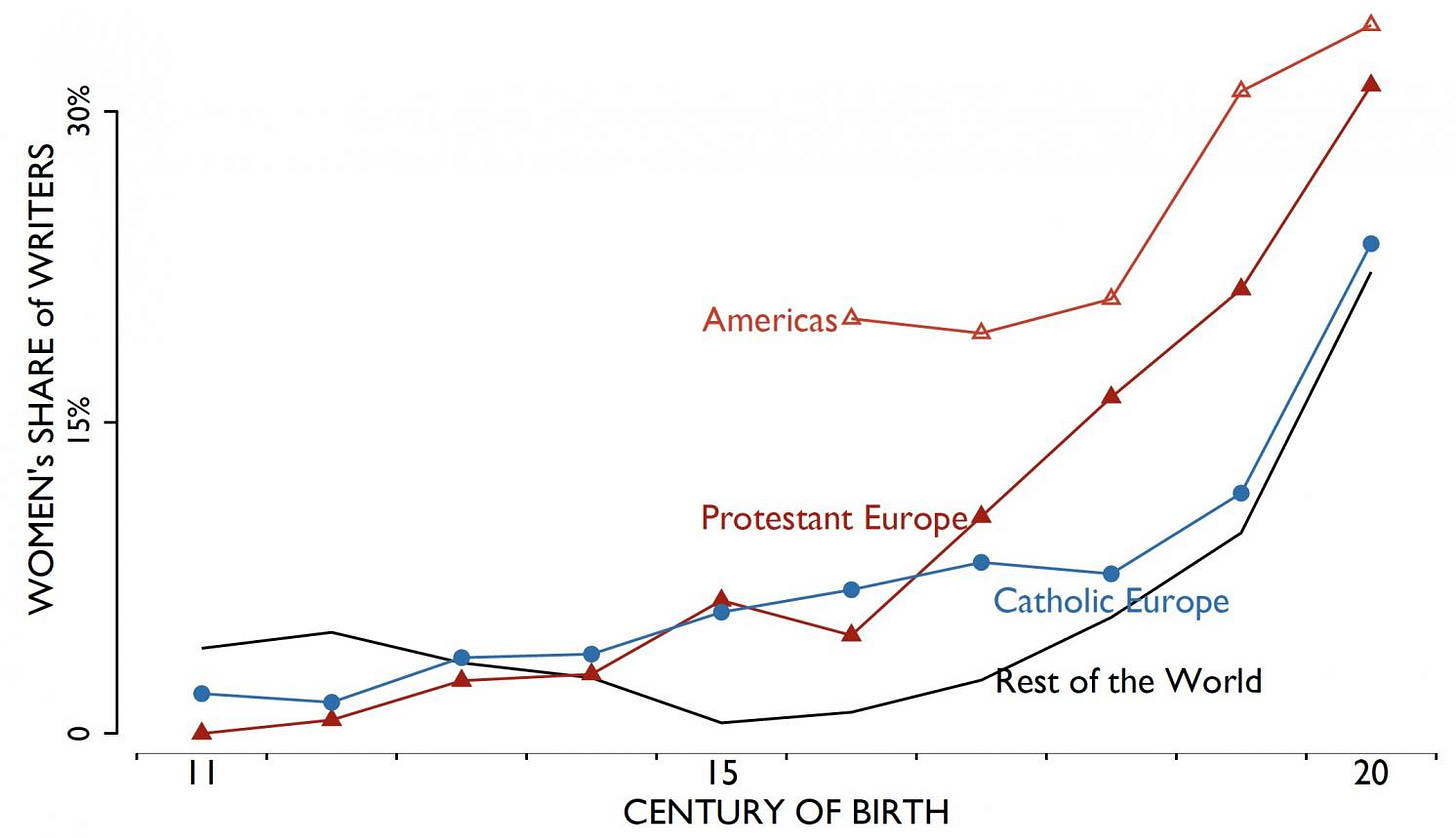

As economic growth expanded the middle class, women writers embarked on a hitherto unrecognised revolution. For the first time in human history, they could reach the literate masses and engage in large-scale ideological persuasion.

Sophie von La Roche (raised as a Pietist) wrote a best-selling novel in 1771, “The History of Lady Sophie Sternheim”. When our heroine enters bourgeois society, she is surrounded by male suitors, each competing with wealth, flattery and power. She herself evaluates men’s sincerity, respect, and devotion. A powerful noble lavishes her with attention, but does not respect her refusal. “No” does not compute. Ultimately, our protagonist judges male behaviour, evaluates suitors, and accepts the man who respects her judgement.

From the 18th century, European bourgeois ‘civility’ was largely defined in terms of capacity to make engaging conversation, including with women. Female choice raised the returns of becoming polite, witty, agreeable, and sociable!

At the same time, marriage was subject to institutional reform. Under Frederick the Great, clerical authority over marriage weakened as the state expanded control over divorce, inheritance, and schooling.

1970s Counter-Cultural Liberalisation!

In May 1968, the streets of Paris became a battleground for liberalism, as students, workers, and residents stacked breeze blocks and overturned cars around the Sorbonne, defying police tear gas to demand educational reform, free speech, and sexual liberties.

Dissent spread across university networks - in West Berlin, Munich and Frankfurt. New counter-publics analysed power and oppression, forming magazines and newspapers like Liberation (1973) in France, Lotta Continua (1969) in Italy, and tageszeitung (1978) in West Germany.

Since Europeans lacked a culture of female seclusion, university students mixed freely. But this also made women vulnerable to violent opportunists. While young men wanted to indulge in sexual freedoms, women sought rights and protections. Activists demanded “Mein Bauch gehört mir” (my belly belongs to me). They demanded respect for their choices and protection from abuse. Popular magazines and sitcoms helped these feminist ideas go mainstream - with trusted characters pursuing careers.

Love, Power & Exit

Europeans came to cherish emotional companionship, but only through two millennia of contestation, in which power was leveraged for wider persuasion. Greco-Romans insisted on marital monogamy, the Church’s demand for consent, Luther’s elevation of partnership, the subsequent turn towards inner conscience, as well as Romanticism’s celebration of emotional authenticity.

All these cultural shifts were pioneered by men, yet inadvertently strengthened women’s status. Once men had legitimised greater freedoms for themselves, women grabbed the pen and pushed for wider application. After Pietism and Romantics extolled the Self, women novelists celebrated their own prerogatives. Two centuries later, as young men lambasted traditional authorities, women expanded those ideals - denouncing shame, demanding autonomy, while simultaneously gaining the economic means to exit. And thus Europeans learnt to love, as equals.

Congratulations to the bride & groom! I am also available for bar mitzvahs, nikahs, and funerals.

Postscript: Modern Implications?

(Omitted from the wedding speech, since it’s a little dark)

European courtship historically rewarded persuasion and companionship. This sharply diverges from societies where female choice is trumped by violent coercion or clan consolidation - like Boko Haram’s abduction of school girls, Kazakhstan’s trend of bride-kidnapping, and South Asia’s suppression of divorce. If men can secure sex and social approval through coercion, skills like pleasing women become superfluous.

Now, if you accept that a culture of courtship disciplined male behaviour, feminist readers will surely wonder how to keep those incentives intact? Here, let me raise two risks.

First, technology may rewire rewards. Hyper-realistic, personalised online entertainment, chatbots and pornography offer low-cost gratification without reciprocity. For men and women who already struggle in competitive mating markets, these substitutes dampen the rewards to developing social skills. Already, we are seeing a rise in solitude and singles.

Even with AI substitutes, most people still seek physical intimacy. Whether that is pursued via persuasion or coercion partly depends on expected punishment. If the state turns a blind eye - or worse, covers up rape - then opportunists can persist with impunity. Last year, 2% of adults in England and Wales said they had experienced unwanted sexual touching or exposure. Simultaneously, there was a 7% increase in rape. In 2024, Germany saw a 9% increase in rape and sexual assault. When men get away with abuse, they have less incentive to play by the rules.

When the government retreats, parents can impose their own prerogatives. 60% of British Pakistani and Bangladeshi marriages are cross-country - usually arranged by kin.

If AI-enabled gratification expands while institutional protection weakens, boys and men may believe there are diminishing returns to being nice.

I enjoyed reading this so much (my poor husband just got bombarded with fun facts on the sofa next to me)! Particularly interesting to see how the sentiment score preceeding the word 'wife' jumped up in the 17th century, absolutely fascinating stuff (ps. I would have greatly enjoyed that wedding speech).

Men make all pairing decision. In the past it was competition through brideprice or other tradeable offers to male parents. Now it's direct and indrect status competition(active and supressed) between men that dictates who has access to ask out and offer things in trade for the right to mate guard her. Like before, offers are collected and vetoed until something is left. Vast majority of women do not make active choice and even in those choices the traits being chosen are functionally identical to what guys detect as success inmale male competition. I'm not arguing it's not better for women, the feminist interpretaiton of 'women have pairing choice now' is an illusion.