How Can We End Alcohol Abuse?

“Drink” is a great social lubricant! From Bavarian beer festivals to Chinese business deals, booze helps us relax, joke and build ties. Chinese job adverts may even call for “good drinking capacity”.

However, it can also create harms: worsening our cognitive functioning, spurring aggression, and is one of the largest predictors of gender-based violence.

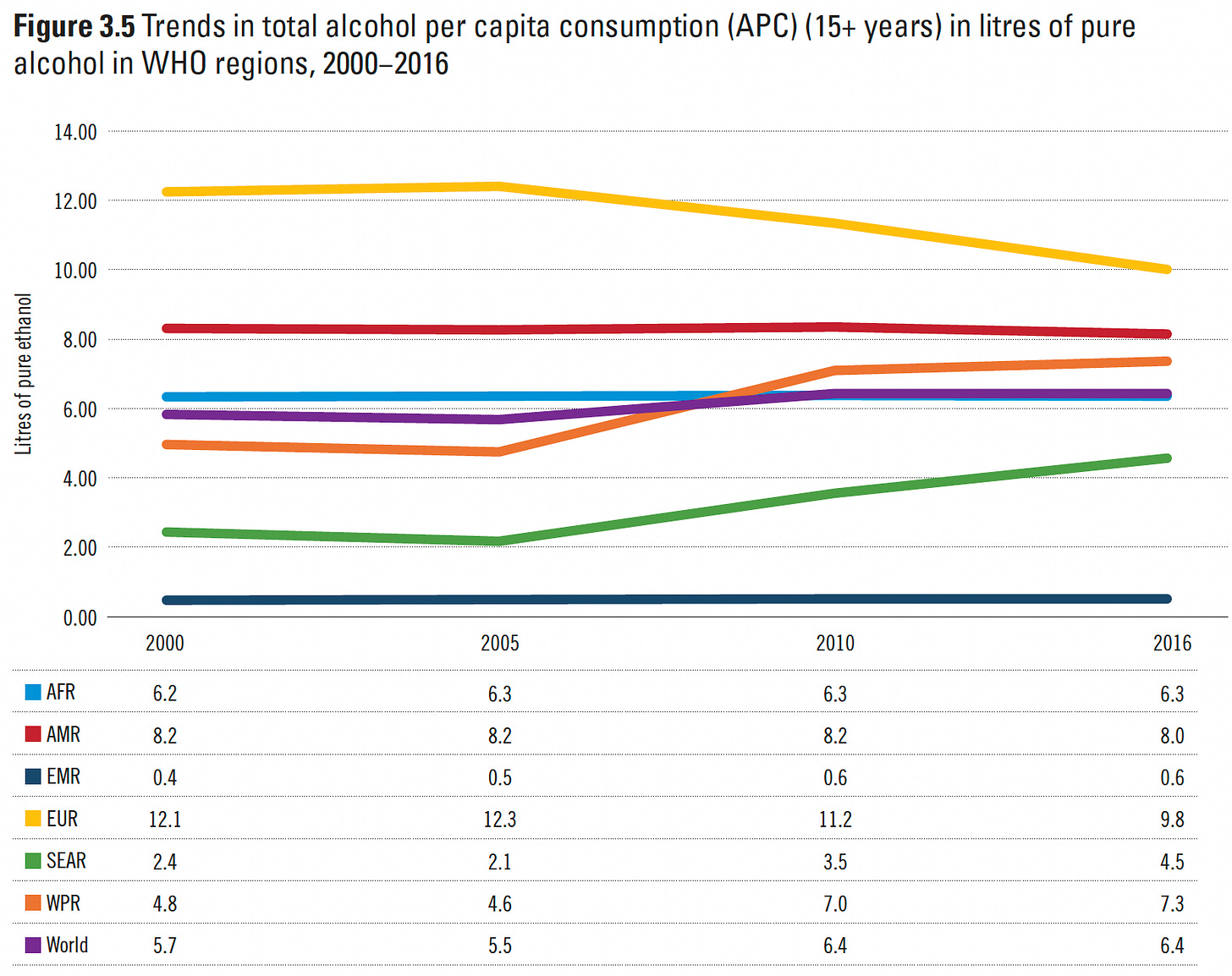

In China and India, consumption is rising. Over in Thailand, 2 in 5 crimes committed by young people involve alcohol. Traffic crashes are the leading cause of death among young men in Brazil, and 78% of these drivers test positive for alcohol.

In this essay, I discuss the latest empirical literature on:

Neurological effects of alcohol

South Africa’s alcohol ban

Russia’s anti-alcohol campaigns

Semaglutide medication to reduce cravings

Deaths of despair and the structural drivers of abuse

Neurological Effects of Alcohol

As blood rushes to the brain it scrambles our prefrontal cortex - a region crucial for decision-making, impulse control, and rational thinking. By disrupting this area’s functioning, it impairs judgment and reduces inhibitions. Simultaneously, alcohol also affects the limbic system, which is involved in emotional processing, potentially leading to mood swings and anger. Alcohol also suppresses glutamate - further impairing cognitive function and memory formation.

The brain’s serotonin and dopamine systems also get hit. Serotonin, important for mood regulation and impulse control, can be depleted by alcohol consumption. This depletion is associated with increased aggression, particularly in individuals already prone to aggressive behaviour. Dopamine, part of the brain’s reward system, is initially increased by alcohol, creating pleasurable feelings. But this can also exacerbate risk-taking.

Long-term alcohol use can cause more permanent neurological changes - principally a reduction in grey matter volume (meaning worse self-control and emotional regulation). White matter, which facilitates communication between different brain regions, can also be damaged, potentially leading to cognitive decline and further problems with behaviour regulation.

By impairing judgment, reducing inhibitions, altering emotional processing, and disrupting the brain’s chemical balance, alcohol creates conditions that can encourage aggression, especially in individuals with pre-existing tendencies towards aggression.

Now let’s consider potential solutions: prohibition, campaigns, and medication.

South Africa’s Alcohol Ban

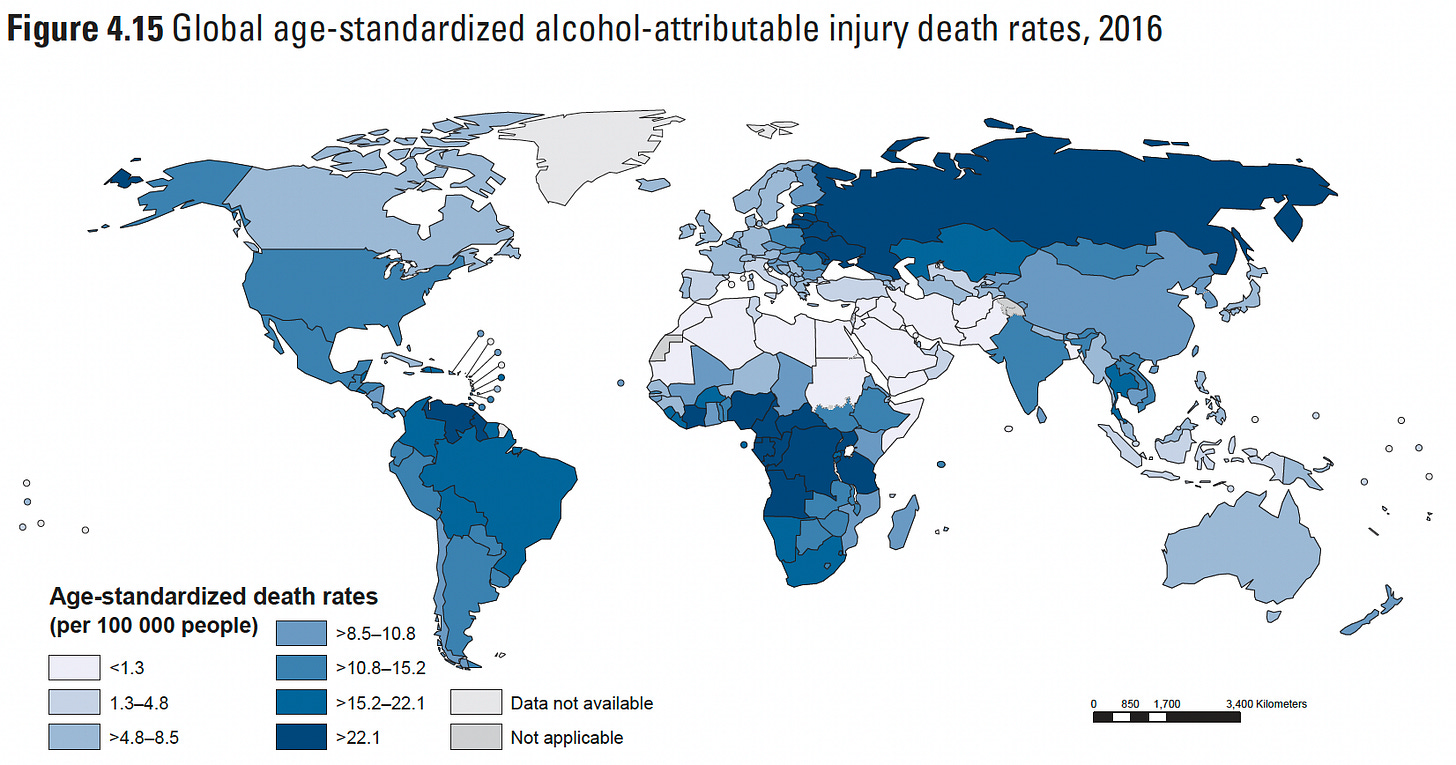

Picture this: It’s dusk in Johannesburg. A young woman hurries home from her shift at the local supermarket, her eyes darting from side to side, keys clutched tightly. She’s afraid, and justifiably so. South Africa has the world’s highest rate of homicides, 42 murders per 100,000 people (compared to 28 in Mexico).

How could the state make her safer?

In July 2020, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the South African government implemented a sudden, complete ban on alcohol sales. The official reason? To free up hospital beds during the COVID-19 pandemic. This abrupt policy change created a unique natural experiment, allowing researchers to examine the causal impact of alcohol restrictions on mortality and violence.

Kai Barron, Charles Parry, Debbie Bradshaw, Rob Dorrington, Pam Groenewald, Ria Laubscher, and Richard Matzopoulos have just published their impact study in The Review of Economics and Statistics. They present compelling evidence of the importance of tackling alcohol abuse.

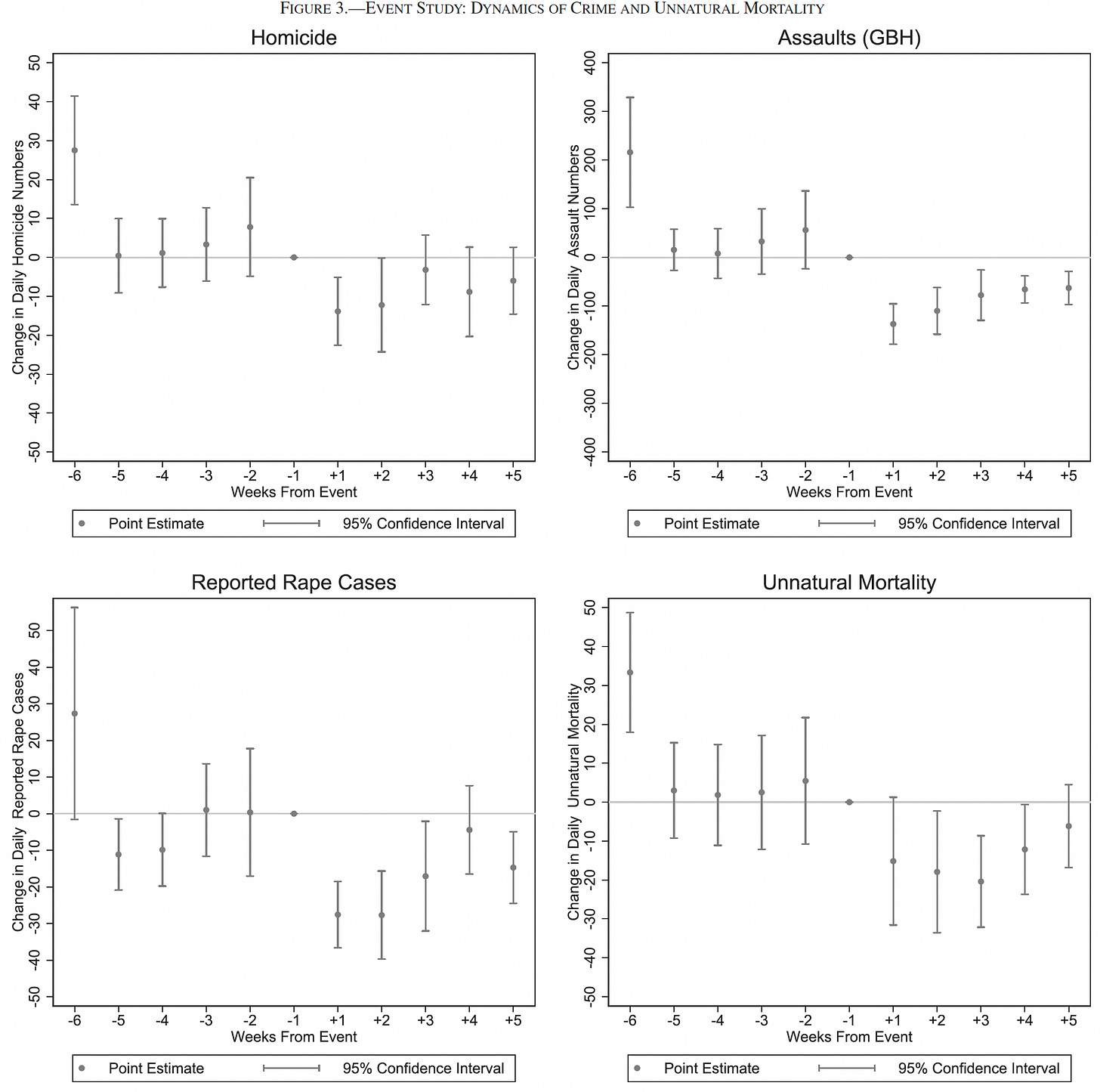

The South African government actually implemented 3 alcohol bans in 2020. Barron and colleagues focused on the second ban, which began in July, as it provided the cleanest natural experiment. This ban was unexpected and occurred midway through the ‘Level 3’ lockdown period, when most economic activities were permitted but a night-time curfew (9pm to 4am) was in place.

The researchers divided the Level 3 period into two parts:

The first half, when alcohol sales were permitted, served as the control.

The second half, with the alcohol ban in effect, became the treatment.

Using a difference-in-difference estimation approach, the authors compared unnatural deaths during the alcohol ban to those in the weeks immediately preceding it. This method allowed them to isolate the effect of the alcohol ban from other ongoing restrictions.

To isolate the effect of alcohol ban from unrelated weekly and seasonal trends, the researchers use day of the week, as well as day of the month and year fixed effects. They also control for a range of COVID era policies.

Banning alcohol dramatically reduced homicides

21 fewer people were killed each day, during the alcohol ban. This represents a 14% reduction compared to the average level during the five weeks immediately preceding the alcohol ban.

The ban appears to have primarily saved the lives of young men:

Male mortality fell by approximately 21 deaths per day, with no statistically significant effect on female mortality.

Half the observed reduction in mortality was among men aged 15 to 34.

But what about the curfew?

Figure 2 shows that when the July alcohol ban ended, there was an immediate and sharp increase in unnatural mortality, despite the curfew remaining in place. This spike in violence and deaths, coinciding precisely with the end of the alcohol ban but not with any change in the curfew, strongly suggests that it was the alcohol ban that reduced mortality.

Visually, it is striking! Every area shaded grey sees a dip in unnatural deaths.

Violent crime was radically reduced:

77 fewer homicides per week (21% reduction)

790 fewer assaults per week (33% reduction)

105 fewer rape cases reported per week (19% reduction)

This reduction in mortality is likely to be a lower bound, since people were already less mobile during the control period due to curfews.

Importantly, Barron and colleagues do NOT present this as evidence for prohibition, but rather as a clear demonstration that alcohol consumption can fuel violence.

Anti-Alcohol Campaigns in Russia

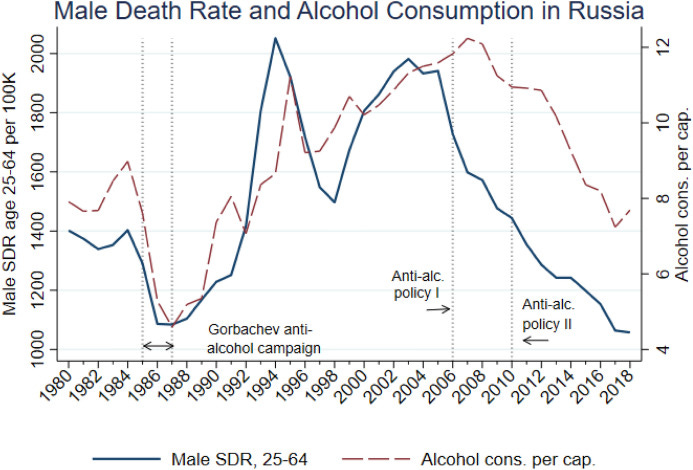

In the Soviet Union, Gorbachev introduced an anti-alcohol campaign from 1985 to 1990. Elizabeth Brainerd and Olga Malkova find that it radically reduced consumption as well as alcohol-related deaths.

However, this did not lead to a sustained change in behaviour.

When the USSR collapsed, the economy contracted by nearly 50%, prices skyrocketed, while violent street gangs wrestled for control. Amid pervasive despair, many turned to drink (as you can see below).

I learnt about this trauma first-hand, while doing research in Poland. Men, in groups of three or four, might sit out in garages, away for several days, losing touch with their loved ones, becoming ever more estranged.

Geopolitical and economic collapse were clearly exacerbating factors, leading many to turn to adverse coping mechanisms. I observed the same in Kitwe, Zambia, where I lived in a dusty shanty compound, right opposite a tavern. Men who had given up all hope often turn to ‘tujili jili’ (40% alcohol). James Ferguson chronicled this too, in his very sad tome, “Expectations of Modernity”. Similarly in the US, rising mortality among non-Hispanic whites has increased amongst the least educated.

So are bans the solution?

Well, another problem is that prohibition also creates risks: ‘Baptists and Bootleggers’. Last year, I stayed in a small town in Alabama which had only recently gone ‘wet’. Previously, people would drive 20 miles, drink, and then drive home!! Not exactly the optimal approach to public safety….

So, what are the alternatives?

Ozempic: Medication to the Rescue?

William Wang, Nora D. Volkow, Nathan A. Berger, Pamela Davis, David Kaelber & Rong Xu conducted a large-scale observational study using electronic health records of over 680,000 patients. Focusing on two groups (83,825 patients with obesity and 598,803 patients with type 2 diabetes), they compared the effects of different medications, one of which was semaglutide.

Caveat: this was only a retrospective observational study, one cannot draw causal inferences. There may be unknown, uncontrolled confounders. That said, their findings were replicated in two different populations, with different characteristics, at different time periods.

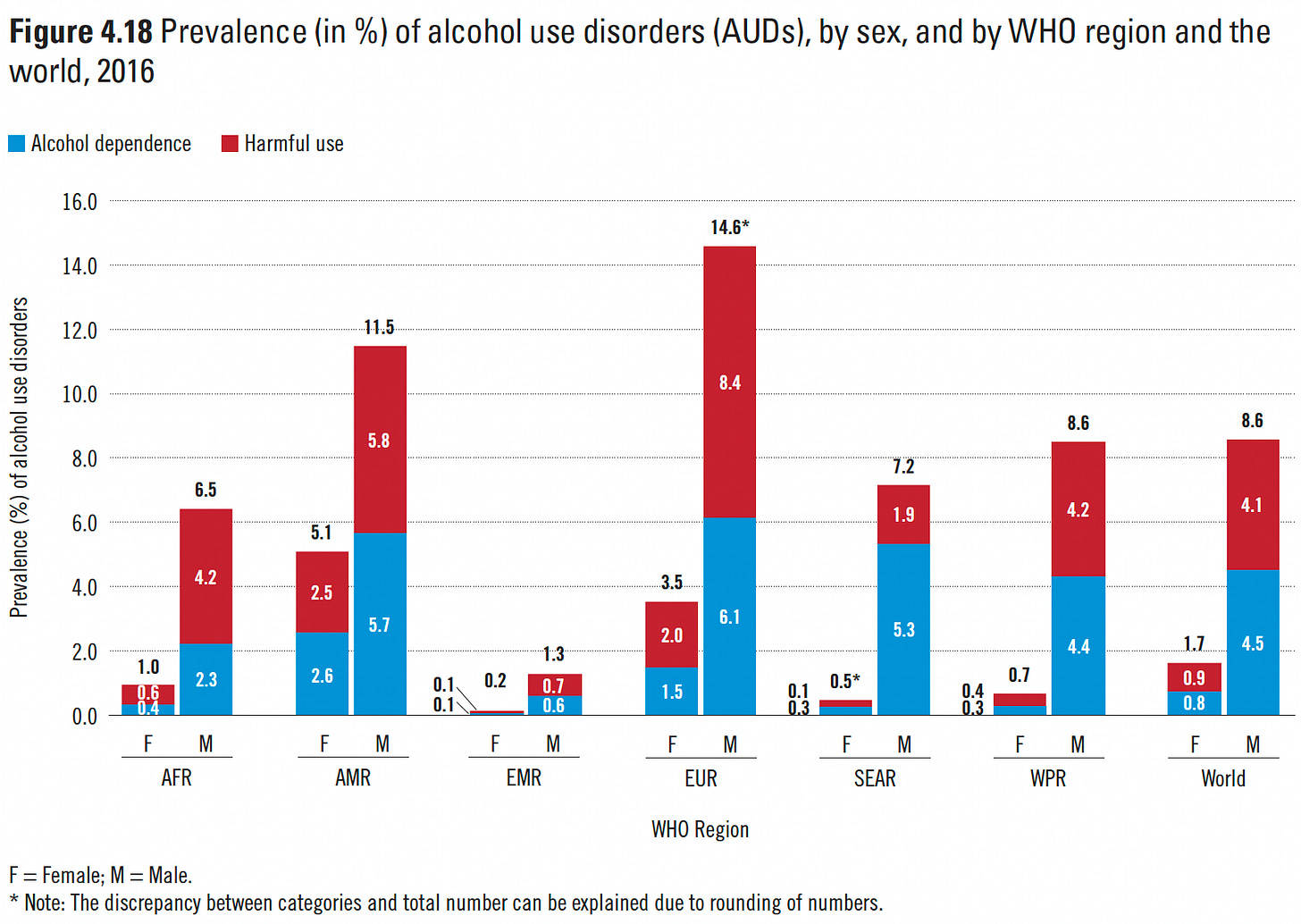

Alcohol use disorders were half as low among those taking semaglutide

In the obesity cohort, semaglutide was associated with a 50-56% lower risk of both new alcohol use disorder (AUD) diagnoses and recurrence in patients with a history of AUD.

Similar reductions in AUD risk were observed in the type 2 diabetes cohort, with benefits persisting for up to three years.

The positive effects were consistent across different genders, ages, and ethnicities.

How Can We End Alcohol Abuse?

The emerging research on alcohol abuse demonstrates the complex interactions between individual predisposition, economic development, alcohol consumption, and violence.

Certain individuals may be pre-disposed to heavy consumption, which in turn seems to exacerbate the risk of violence. Both factors can be addressed - either by reducing cravings or restricting access. This in turn seems to reduce violence.

Other effective alternatives include Islamic proscriptions, high taxation, and drink-driving campaigns - which obviously require state capacity.

Taking a globally comparative perspective, we also see a varying relationship with economic growth. In China, rising incomes may have enabled increased spending on alcohol, which lubricates social ties of ‘guanxi’. Whereas in the USSR and Zambia, deaths of despair shot up during economic crisis. Likewise in the US, the rise in prime age mortality was concentrated among the most disadvantaged. Understanding country-specific drivers is obviously an important part of any solution.

Related Essays

Can We End Alcohol Abuse? [my earlier review of the evidence, 2023]

Further Resources

Kajol Sontate, Mohammad Rahim Kamaluddin, Isa Naina Mohamed, Rashidi Mohamed Pakri Mohamed, Mohd. Farooq Shaikh, Haziq Kamal, and Jaya Kumar, Alcohol, Aggression, and Violence: From Public Health to Neuroscience

Kai Barron, Charles D. H. Parry, Debbie Bradshaw, Rob Dorrington, Pam Groenewald, Ria Laubscher, and Richard Matzopoulos, 2024, Alcohol, Violence, and Injury-Induced Mortality: Evidence from a Modern-Day Prohibition

William Wang, Nora D. Volkow, Nathan A. Berger, Pamela B. Davis, David C. Kaelber & Rong Xu, 2024, Associations of semaglutide with incidence and recurrence of alcohol use disorder in real-world population

Ria Ivandić, Tom Kirchmaier, Yasaman Saeidi, Neus Torres Blas, 2024, Football, alcohol, and domestic abuse

Elizabeth Brainerd, 2021, Mortality in Russia Since the Fall of the Soviet Union

Paul Novosad, Charlie Rafkin and Sam Asher, 2022, Mortality Change among Less Educated Americans

One thing I am curious about is why tobacco use has been treated like a public health concern with governments and other respected institutions actively and loudly discouraging its use, and alcohol has not been treated that way. As the campaign to reduce smoking has been very effective in the US, so it is easy to imagine that a similar campaign against alcohol use succeeding in dramatically reducing alcohol consumption and problematic alcohol use. My best guess is that alcohol is tied to social rituals in a way that cigarettes were not, and also that cigarettes were not viewed as fun either. So being against cigarettes wasn’t viewed as being a killjoy, nor did it interfere with rituals like toasts at weddings or other celebrations, or other social activities. But that is just a guess. Also, the campaign against cigarettes was never associated with religion so far as I know, nor so far as I know with gender, whereas the temperance movement in the US was associated with Protestants, rural areas, and with feminism. I also wonder about social class, as I have read that wealthier and more educated people drink more than others in the US. So desiring to see less drinking in the US would look like something low status.

Within our lifetime semaglutide may become as consequencal as condoms and birth control pills were in the 20th century. Techno-optimism for the win.

We might be a revival of the temperance movement of the early 20th century.