Did female driving increase Saudi patriarchy?

After women’s driving was legalised in Saudia Arabia, did they gain autonomy?

No. First up, the driving course was prohibitively expensive ($800 USD; six times higher than the course for men). Two years after the ban was lifted, only 2% of Saudi women even had a license.

Chaza Abou Daher, Erica Field, Kendal Swanson and Kate Vyborny then enacted a cunning plan to test the effects of actual driving: they randomised free driver training! 54% of respondents in their treatment group gained a license, compared with 10% of respondents in the control.

Did driving expand female freedoms?

Two years later, women in the treatment group were

61% more likely to drive;

19% more of their trips were unchaperoned;

35% more likely to be employed, BUT..

19% more likely to require permission to make purchases.

How come women both gained and lost autonomy??? The answer is that the effects diverged by marital status. Driving enabled more unmarried women to travel independently, get jobs, and exercise financial autonomy. Wives, by contrast, were immobilised.

Married women (who could drive) were less likely to travel unaccompanied.

Married women (who could drive) exited the labour market. Unmarried women entered the labour market. The authors observe:

48% decrease in employment among women who are married or divorced with children.

38% increase in employment among women who gained the opportunity to drive and are never-married, widowed, or childless divorcees.

Married women (who could drive) recorded lower spending autonomy:

Only 36% of treated women with husbands/ co-parents say they are allowed to make purchases up to SAR 1000 (equivalent to USD 265) without family approval;

53% of women in the control group say they can make these decisions alone;

44% of never married/ widowed/ childless divorces can spend alone.

Congratulations to the authors for getting under the bonnet of Saudi patriarchy! This is such a clever design, with awesome analysis of heterogeneity. Bravo.

Why might driving worsen married women’s employment & spending autonomy?

Abou Daher and colleagues offer two explanations: male guardianship laws and altruism.

Each Saudi woman is legally under a male guardian. Before marriage, it is her father; then husband; and if she is widowed/ divorced then guardianship returns to her natal family. Although women are legally entitled to employment without approval from male guardians, in practice employers want to see this in writing. Her exit options are weak. Less than 1% of divorces are initiated by women. Even if divorced, the child’s father still has legal guardianship over the children. Legally, therefore, women must negotiate employment with male guardians.

The Quranic decrees that men are responsible for household financial provision, while women entitled to their own earnings. Abou Daher and colleagues posit that individuals may be more altruistic towards offspring than spouses. Accordingly, self-interested husbands are more likely to refuse permission.

“Purely self-interested men are less likely to be supportive of female employment than they would be if household members' labor income were fully pooled, and altruistic household heads - who more fully internalize the utility benefits to women from working - are more likely to support female employment” (Abou Daher et al 2023).

Sorry, but I am not convinced.

Even if wives only spend on themselves, this still reduces men’s burden.

Even if mothers are not religiously obliged to spend on their children, they may still choose to. Income pooling is common. The authors actually contradict this in their own model, because they posit heightened altruism towards offspring.

The presumption of greater altruism towards offspring than spouses seems unwarranted. Many people love their spouses and make huge sacrifices!

If the religious institution of nafaqah (male financial responsibility) was the major factor, then wives’ employment would be similarly low across all Muslim countries. In fact, there is great heterogeneity. Back in 1960, Saudi female labour force participation was only 3%. In Muslim West Africa and South East Asia, women are twice as likely to work. Interpretation of scripture is always mediated by culture.

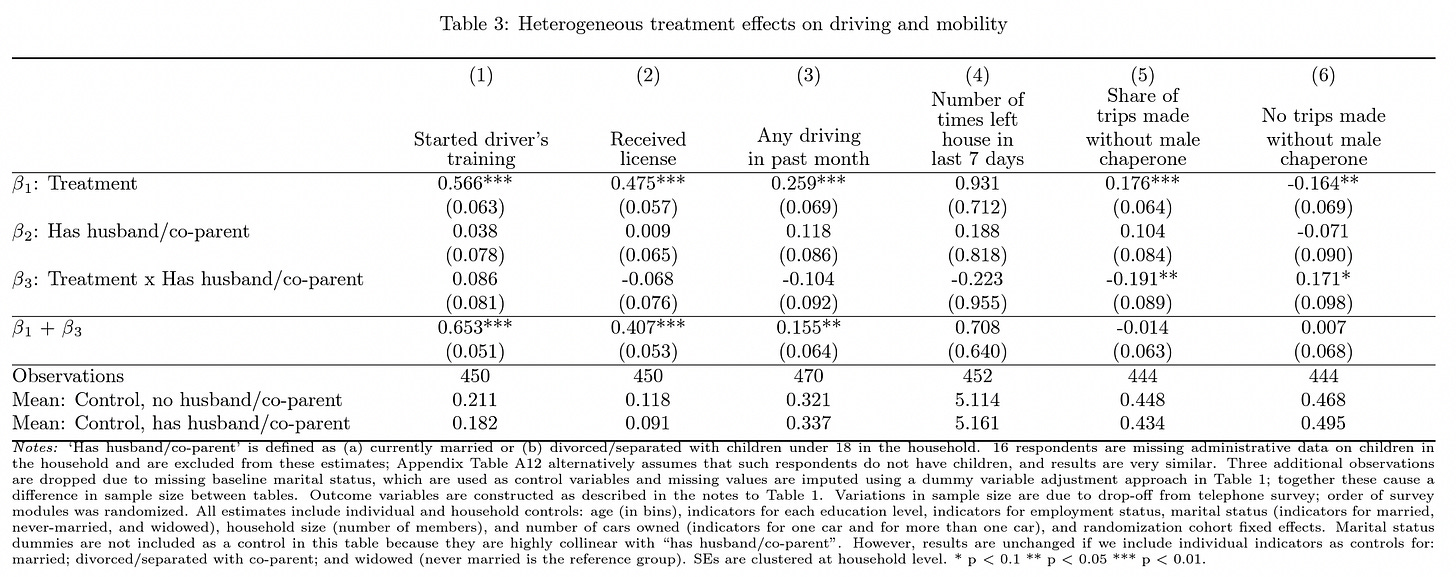

Abou Daher et al’s Table 3 suggests it’s not about financial provision but patriarchal control. After married women started driving, they made fewer trips unaccompanied.

Male Honour and Female Seclusion

For insights into Saudi culture, I strongly recommend a wonderful book by Aurelie Le Renard. As late was the 2010s, the religious police (CPVPV) bellowed over a microphone:

“Cover your face”

“Cover your eyes”

“Wear the abaya of Muslim women”.

Saudi women were publicly reprimanded, “in front of everyone”. Arrest was even worse. “People think that if the Committee [hay’a] have arrested someone, there must be a reason, shared 22 year old Amal.

Visiting friends may be prohibited, since this is considered dangerous. Four female close friends at university (interviewed by Le Renard) spent every break time together, but had never been to a cafe outside campus. The one time the four women met, their mothers came along as chaperones.

“Kalam al-nas” is a common concern: what will people say?. Reputations are zealously guarded. Young women self-police and zealously observe gender segregation, so that their families do not heighten restrictions.

Honour within close-knit tribes is contingent on eliminating all possible suspicion of impropriety. Saudi women may try to persuade their parents to be more lenient not through reason or scripture, but showing wider acceptance:

“The crux of the negotiation is to convince the family that a certain behaviour is the most accepted, the least stigmatised in the eyes of those who count”.

However, Le Renard observes that it is considered prestigious to have a daughter employed in a high position. A daughter may get a job iff there is no loss of honour.

Saudi husbands care deeply about their reputations and stop their wives from working because they anticipate stigma. This has been empirically demonstrated by the well-known paper: “Misperceived Social Norms”. In this Randomised Control Trial, married men were informed that female employment is actually more widely accepted. Their wives were subsequently more likely be employed.

The qualitative and quantitative research on Saudi Arabia thus lends support to an alternative interpretation of Abou Daher et al’s descriptive data on driving.

Legal reforms and free driving lessons do not undermine a culture of honour

If rumours of female impropriety can ruin family honour, then women’s increased capacity for physical mobility may just trigger patriarchal clampdowns.

After wives could drive, husbands increasingly pulled the breaks and effectively impounded their wives. Many were likely concerned for “kalam al-nas” (what will people say?). Driving was only permitted if chaperoned.

Why do the effects vary by marital status? In honour cultures like Saudi Arabia, female employment falls upon marriage. Married men want their wives at home.

But change is afoot. Saudi female employment has actually risen in recent years, the government has removed restrictions, signalled approval, and women are capitalising on new opportunities in private firms. As more women work, this signals wider approval. Others cease to anticipate stigma. They are starting to overcome what I call “The Honour-Income Trade-Off”.

Congratulations to Chaza Abou Daher, Erica Field, Kendal Swanson and Kate Vyborny on a fantastic RCT. I differ in interpretation, but LOVE this paper. Bravo!!

Is the higher price of female driving courses related to not being many female instructors available to give course and therefore very high salaries for these instructors? Am I wrong in assuming that instructors for female students must be female?

Yes. It’s rare and unregulated. People are profiting off of women’s back and when I say people I mean other women. I am in Saudi, that’s what my friends told me.