Are 🇺🇸 Sexual Predators Ostracised?

Evidence from the US

Rainer Widmann, Michael Rose and Marina Chugunova have a fascinating new paper on whether sexual predators are professionally punished. Before digging into the empirics, tell me your priors:

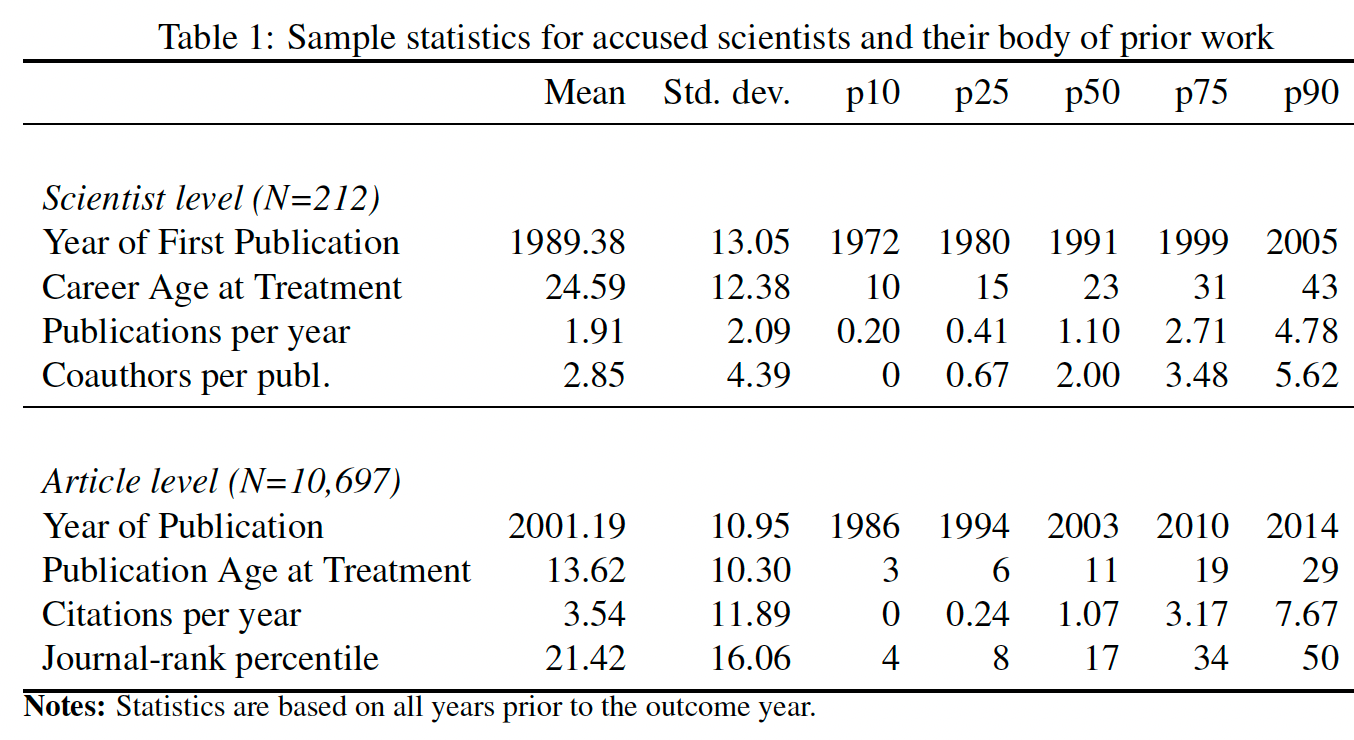

Widmann and colleagues identified 212 scientists at research-intensive U.S. universities who faced public allegations of sexual misconduct between 1998 and 2019. Cases were included only if there was substantive action taken in response to the allegations. They then connected accused scientists to their publication profiles in the Scopus database, tracking citations to their prior work over time.

Citations to accused scientists’ papers were compared to control articles from the same journal issues. Matched control scientists with similar characteristics were included for comparison (i.e. people with similar productivity, but no accusations of molestation).

Widmann and colleagues examine network effects: how do citation patterns change based on the distance between citing authors and accused scientists? How does this vary by gender? And what happens to accused scientists’ careers?

Ostracism

When scientists at US universities are publicly accused of sexual misconduct, their prior work typically receives about 5.25% fewer citations. This decline is most pronounced among close collaborators, especially among men. The effect appears to be less strong in male-dominated fields.

Figure 1 Panel A below shows that when allegations become public, citations drop. Panel C shows that this effect is strongest among direct co-authors, with male authors showing a much stronger reaction (-38.53%) compared to female authors (-19.80%). Panel D compares male-dominated fields with other fields. The effect is much stronger in fields with more than 20% women.

Let me add some important qualifications. The sample size is small (212 known abusers), the average article doesn’t get many citations, overall effect sizes are quite small, and the confidence intervals are large. We need more evidence..

What happens to accused scientists’ careers?

After sexual misconduct is publicised, accused scientists tend to publish less (Panel A) and collaborate less (Panel B). 80% of the decline in collaborations is due to accused scientists leaving academia.

Accused scientists are 24% less likely to continue publishing. Among those who do continue publishing, accused scientists are less likely to stay at the same university (28% vs 58% for controls). Accused scientists are more likely to move to non-university institutions (17% vs 6%) (Panel C).

(Unfortunately, they do not control for age. So I don’t know how many of these abusers were already verging on retirement. Nor do they control for whether the field is male-dominated. Would be great to see!).

How should we interpret these findings? Well, known abusers are highly likely to be institutionally ostracised. That said, 28% do remain at their universities. Frankly, I’m not sure whether that indicates leniency because the underlying dataset does not state the severity of abuse. So I’m unsure whether 28% is high or low.

My interpretation?

Fraternal networks are a major driver of patriarchy, especially in cases of sexual abuse. Men may be inclined to protect their friends, and keep accountability mechanisms weak, lest they also be charged. Throughout global history, victims have been disparaged and denigrated.

But in the late 20th century, something extraordinary happened. Millions of women gained control of their fertility, furthered their education, and pursued careers. Gaining strength in numbers, they increasingly criticised sexism and sexual predation, creating negative penalties. Norms shifted - in two ways. By listening to survivors, others may have become more empathetic. Another potential motive is more strategic. Men may be more inclined to disassociate themselves from known abusers in order to preserve their reputations. Either way, women’s incursions into historically male-dominated domains has changed the rules of the game.

Philosophy’s #MeToo

Let me give an example from Philosophy (which is very white and very male).

In 2010, Fernanda Lopez Aguilar, a recent Yale graduate and migrant from Honduras, accused world-renowned Yale Professor Thomas Pogge of sexual harassment, groping, and promising her with careers prospects. Yale administrators replied she had no recourse, since she had left. $2,000 was offered on condition of confidentiality. Despondent, Lopez Aguilar signed.

The following year, 16 students filed a Title IX complaint with the Department of Education, accusing Yale of ignoring other cases of sexual misconduct.

Lopez Aguilar tried again, bringing an official complaint. Yale’s Committee on Sexual Misconduct found insufficient evidence. In preparing her case, she discovered two other young women from low and middle income countries, who also accused Pogge of sexual misconduct. Critics allege that Yale knew about similar allegations at Columbia even before they hired Pogge. Yale arguably turned a blind eye to protect their reputation and an esteemed scholar.

Seyla Benhabib, a professor of political science and philosophy at Yale, observed,

In 2016, these charges were widely publicised. The New York Times wrote a highly critical piece, condemning fraternal cronyism. There was a surge in public solidarity. 169 philosophers signed an open letter condemning Pogge’s sexual harassment.

“You don't need him. He carries too much baggage -- he doesn't have to be cited anymore. He's a negative image and we don't need that. Maybe if he was Einstein we'd have to cite him, but he's not” - James Sterba, Professor at Notre Dame.

Was this just talk? Curious, I checked Pogge’s Google Scholar yearly citations. After 2016, they plummet from 2814 to 570.

Pogge is just n=1 highly publicised case. But it is consistent with Widmann and colleagues’ findings from 212 known abusers and ostracism.

The struggle for accountability continues

Bullying, harassment, and misconduct persist. As I see it, there are 2 major issues:

Victims may be inclined stay quiet, for fear of jeopardising networks amid an extremely adverse academic job market.

Universities may suppress complaints to prevent adverse publicity. A recent BBC investigation found that a third of UK universities had used Non-Disclosure Agreements. Seldom seeing accountability, other victims may remain despondent and self-censor.

What might help?

Better exit options - alongside job-creation.

Publicised peer disapproval in media or movies. Popular television shows might portray ordinary men chiding their peers for sexual harassment.

In 2021, UK politician Andy Burnham launched an excellent campaign, #IsThisOK, urging zero tolerance.

Related Essays

H/t the brilliant Florian Ederer, who has done pioneering research, quantifying abuse in Economics.

I think the strength or perceived strength of evidence may be a big factor and this aspect is completely missing from this article.

There are huge cultural norms around presumption of innocence, around better let 100 guilty go than punish one innocent, on protecting the accused's rights - habeas corpus is nearly 900 years old.

Feminists have been trying to shift it because in such cases evidence is nearly impossible. They do have a point - if Bob takes my bike from my garage, I should have to prove at court that I did not consent to it? How? If Bob beats me up, I should prove at court it was not a consensual BDSM play? Obviously these things are not provable.

But such a huge thing is just hard to shift and besides what exactly should replace it? Just believing all accusations is clearly not an acceptable replacement.

In old times, the rigid sexual norms maybe helped with convincing people. Just like people beating up some on the street is very unlikely to be consensual BDSM play, and no one would believe such a claim, back in old times no one would have believed the plumber saying that a random housewife consented to sex with the plumber fixing the pipes. But these norms have shifted - now hookups are an accepted part of culture and it makes lack of consent so much harder to prove, to convince people of it. We longer have an argument that in this particular situation consent would have been *unlikely*.

Kevin Spacey's legal defense sounded basically like Hollywood is full of gay men and all of them want him. 100 years ago it would have sounded ridiculous, but today - who knows? We no longer know in what situations is consent *unlikely*

But now there is a new norm slowly emerging: multiple similar accusations are to be believed. But it is unclear how many. Still ultimately multiple similar accusations establish a... reputation. Sexual harassment is not a one-time action but a general attitude and habit, and sooner or later it gets known.