President Trump has announced major cuts to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). This threatens millions of lives worldwide.

While I cannot do justice to the vast literature on aid effectiveness, let me provide a snapshot of how aid has dramatically improved human health and what cuts mean for the world’s poorest.

We’ll start with the big picture – has international aid actually helped? After reviewing global progress on infant mortality, smallpox and HIV, I’ll share my research from Zambia, where the government has dramatically reduced maternal mortality through data-driven accountability. Finally, we’ll consider USAID’s groundbreaking collaboration with UNICEF, Open Philanthropy and the Gates Foundation to tackle lead poisoning.

Global Progress on Health!

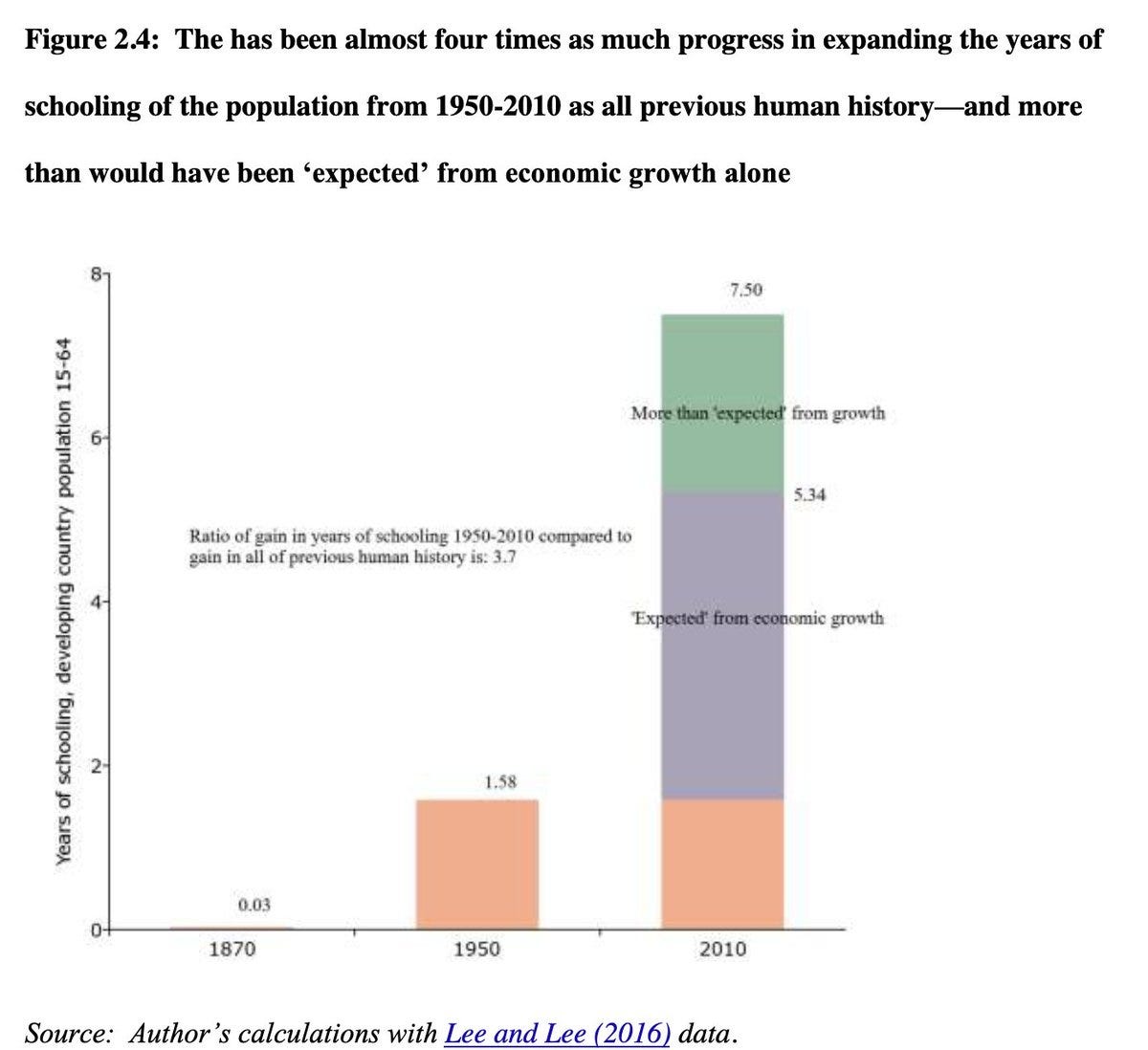

At the big macro level, Lant Pritchett considers whether aid has helped. As you can see, there has been a massive reduction in infant mortality and an expansion of schooling - more than would be expected from growth alone. One compelling explanation for these improvements is international aid.

Smallpox

Smallpox previously killed more people throughout history than all wars combined, causing disfigurement, blindness, and death to millions. At a relatively small cost of $1.5 billion, it was successfully eradicated in 1980.

As Owen Barder calculates, even if this was all that aid had ever achieved, then it would still have been extraordinarily cost-effective at just $78,300 per death averted - far below standard health spending thresholds in high-income countries. The smallpox program itself was actually much more remarkable, costing just $25 per death averted, making it arguably the most cost-effective intervention in human history.

HIV/AIDS

Since its creation in 2003, the United States President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) has directed over $100 billion toward fighting HIV/AIDS globally. It has saved more than 25 million lives and prevented millions of new infections.

Experts should correct me, but to the best of my knowledge, no other interventions have been effective. What worked is building healthcare systems and providing life-saving drugs, which also suppressed the virus and reduced risk of transmission.

Currently, PEPFAR provides lifesaving treatment to 20.6 million, including half a million children. Halting this funding risks triggering a resurgence of HIV.

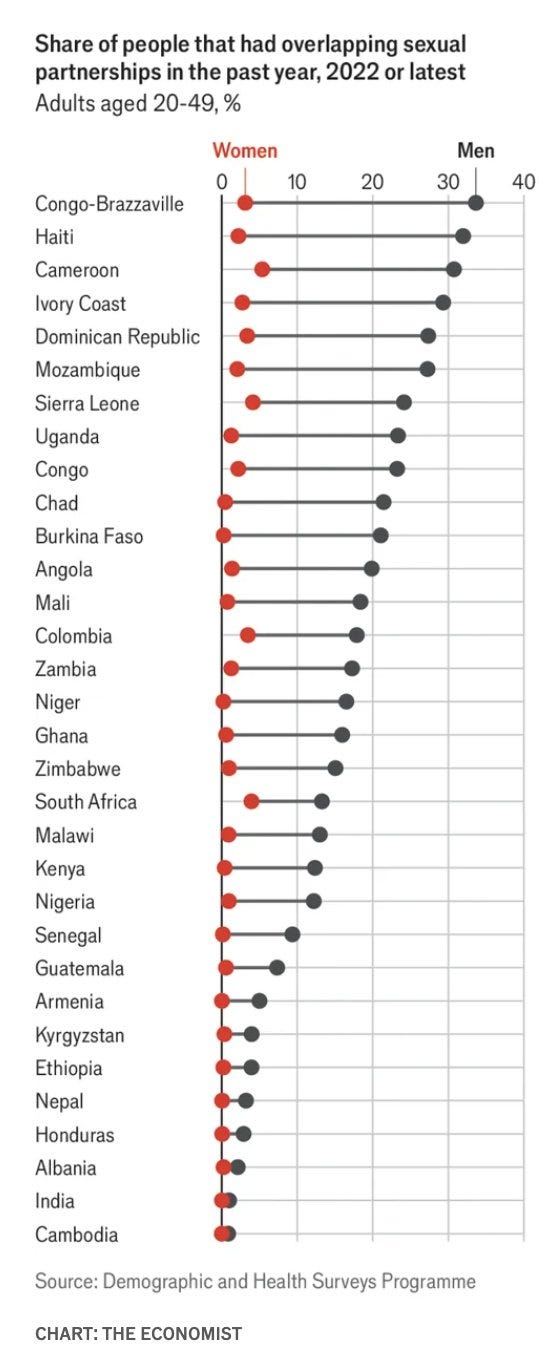

Trump’s Cuts to Demographic & Health Surveys

Cuts are also hitting Demographic and Health Surveys. For many low and middle-income countries, these are the only sources of nationally representative data on maternal and child health, mortality, nutrition and HIV infections.

Why does data matter? Well, my research in Zambia suggests data was actually vitally important - enabling performance accountability and peer competition.

Safe Motherhood!

Over the past three decades, Zambia has achieved remarkable success in reducing maternal mortality, while increasing skilled birth attendance and family planning.

When I first saw this data in 2012, I was instantly curious! What had enabled this fantastic improvement in women’s lives? I had just finished my PhD, and had neither a job nor any grant money, but I was fluent in Bemba (a local language) and wanted to learn! Scrimping together my savings, I returned to Zambia.

Methodology: Studying the Drivers of Change

Keen to understand Zambia’s exceptional success, I investigated both the political prioritisation of maternal health and also effective implementation. This required a multi-level ethnography over several years, working with both local and central government. Supported by Zambia’s Permanent Secretary for Health, I joined frontline healthcare workers in rural clinics, district health managers, provincial administrators, national health officials, parliamentarians, and former Ministers of Health. In total, I conducted in-depth interviews with over 50 participants, many interviewed repeatedly over several days.

I was seriously embedded. For three months, I lived alongside parliamentarians at the National Assembly Motel and separately with a government minister. Together, we attended parliamentary sessions and workshops. Generously, the Ministry of Health let me join a shared office alongside other civil servants.

At the frontline, I joined three neighbouring rural District Health Management Teams. These each had similar socio-economic and geographic profiles but different maternal healthcare indicators. I wanted to understand why some districts performed better than others. With their support, I was observed daily realities.

After completing my research, I shared and discussed my written summary with senior civil servants, Cabinet Ministers and even the Vice President.

How I Built Trust & Connections?

My fluency in Bemba - for which I created my own dictionary and studied an old grammar book made by missionaries - helped convey respect. I was repeatedly invited to discuss my findings on television and radio, and since there weren’t many channels, these were widely seen and I became rather well known..

Whether I was wedged in a bus traversing pot-holed roads in Kalulushi, hailing an unmarked taxi in Kitwe, queuing at Shoprite in Luanshya (90 km west) or passing provincial ministers in Lusaka (388 km south), many people knew my Bemba name (Mapalo) and my research on safe motherhood. Sometimes I would board a bus, get spotted and then everyone would start singing!

Once, after many hours of hitch-hiking on lorries, I arrived at a Maternal and Child Health Coordinator’s home and presented my formal letter of introduction, signed by the permanent secretary. Beatrice laughed:

“Oh there’s no need for that! I already know who you are, Mapalo!”

We had never met, nor had I ever before been to this very remote region. Yet Beatrice was instantly at ease, inviting me to stay at her house. Parliament was much the same - a former Minister publicly chided me for not having interviewed him sooner!

In December 2012, I got really lucky. My flight was full of American and European diplomats and aid workers going home for Christmas. Alas, our plane journey interrupted by heavy snow and forced to land in Madrid, where we were stranded at the same hotel for several days. Naturally, I interviewed them all!

Yes, I get around. Now let’s dig into the data!

Amplifying accountability by benchmarking results at district and national levels

Around 2006, Zambia’s senior civil servants and politicians realised that other African countries were making much faster progress toward Millennium Development Goal 5 - on safe motherhood. Senior leaders expressed their embarrassment of lagging behind.

“MDGs - we have to be part of the world … We found that we are not on track. The commitment has been there but it was enhanced by the MDGs”.

“We are a stable country; to be put in that place is a shame [points to sharing rankings with conflict-afflicted states]”.

“If you look at our performance towards the MDGs, the only indicators that are quite a challenge are MDGs 4 and 5, so it prompted us to say, “what can we do?” To meet the targets we need to do some extraordinary things”.

When shown regional statistics during planning meetings, one Maternal and Child Health Coordinator exclaimed, “No, Zimbabwe can't do better than us!”.

Performance benchmarking led Zambian politicians and civil servants to see that other African countries were successfully making progress. Leaders soon realised that maternal health could be rapidly improved, and this was increasingly part of their geopolitical standing. With increased gusto, the Zambian Ministry of Health institutionalised a series of reforms:

Institutionalised MDG Target 5.2 (the proportion of deliveries attended by skilled health personnel) as its own Performance Assessment Indicator

Launched a national program in 2007 to strengthen Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care

Created a separate budget line in 2009 for reproductive health

Implemented Maternal Death Reviews in all districts, and

Increased government expenditure on family planning commodities.

Previously, in annual meetings, maternal health indicators were quickly skimmed. With greater prioritisation and conditional funding from donors, health officials increasingly scrutinised the data and underlying bottlenecks. Together, they developed a shared mission. As managers explained,

“There would be threats of delayed release of money [by donors providing Sector Budget Support], if there were poor indicators. It helped us mobilise more resources, they said, ‘Why is it not improving?’ It allowed us to raise issues”.

“By putting in that indicator on skilled attendance that was a trigger to recruitment, to have more nurses and midwives, so that brought in the Human Resource Strategic Plan, scaling up the Retention Scheme and increased funding for medical training institutions. After two years we had doubled the production for nurses”.

“When issues came in, everyone in management was very supportive and wanted to be involved. When budgeting, they [the government] agreed to include reproductive health commodities, e.g. contraceptives”.

Benchmarking Results Drove Local Competition

As senior civil servants increasingly prioritised maternal health indicators, district health officers quickly sought to improve.

“All of a sudden, we dropped to among the last districts in terms of MCH performance” explained one District Maternal and Child Health Coordinator. “So a number of follow-ups have been made both by the national office and the provincial office. That’s what made people sit up”.

This changed her District Medical Officer's behaviour: “If the indicators are going down, he will make an appointment with me. He will ask questions like, ‘Is it me that makes you not perform well? If there's anything I'm doing let me know”.

Because he knows that at the end of the day his name is tarnished. He will be said to be a non-performer, so he gets concerned, he tries to dig deeper to find out why the district does not perform to expectation”.

Top-down accountability and benchmarking results enabled learning, emulation and competition between districts. One district manager explained how seeing data from neighbouring areas motivated improvement: “When you see that District X is doing better than us, we sit down and say “What can we learn from them?’”

In better-performing districts, health workers consistently emphasised the importance of supportive supervision - with managers providing both genuine concern, compassion and rigorous analysis of the data. As one healthcare worker explained, without monitoring

“you become relaxed a bit. But when they come for Technical Support they've got no time to see all our records. They just depend on what we tell them, so you can lie”

As part of my research, I also investigated the possible impacts of community-driven accountability and awareness-raising. These paled in comparison to top-down accountability and benchmarking results.

Top-Down Accountability and Benchmarking Results

Data is no panacea, it can certainly be ignored. But in this specific case, data was absolutely fundamental! Zambian leaders saw that other African countries were making rapid progress, which raised their expectations about what was achievable, catalysed status competition, and led to top-down prioritisation of maternal health.

Trump’s cuts to USAID and DHS threaten to undermine the very mechanisms that drove remarkable progress: data-driven benchmarking and accountability. Without accurate data, governments lose the ability to compare to their peers and identify areas for improvement.

Developing countries with limited statistical capacity rely heavily on international support for their data systems. Without these systems, Africa’s impressive gains in health are at risk. Problems become invisible and accountability weakens.

A Lead-Free Future?

Lead poisoning rots children’s brains - thwarting their cognitive development, educational progress and risk of violence. 800 million children worldwide have elevated blood lead levels, predominantly in low and middle-income countries.

In 2024, a fantastic breakthrough came with USAID, UNICEF, Open Philanthropy and the Gates Foundation launching “The Partnership for a Lead-Free Future”. This alliance brings together 30 governments and 36 civil society organisations to tackle a poison that kills over 1.6 million people annually.

Change is certainly possible! Coordinated efforts in Georgia reduced elevated blood lead levels in children from 60-80% to just 20% within five years. In Bangladesh, targeted interventions rapidly reduced exposure from adulterated turmeric.

In Nigeria, USAID was supporting the government’s efforts to protect children from lead exposure - caused by lead-acid battery recycling. Trump’s cuts threaten to derail this progress.

Aid Saves Lives

Thanks to global partnerships and scientific advances, we’ve seen massive improvements in maternal and infant health. PEPFAR saved 26 millions helped reduce HIV counts, reduced transmission and enabled people to enjoy their lives!

In Zambia, I witnessed first-hand how data-driven accountability enabled safe motherhood. Peer comparisons motivated improvements at multiple levels – government officials concerned about national rankings, health administrators concerned for performance metrics, district teams eager to outperform and compete! Demographic Health Surveys weren’t just providing statistics – they enabled governments to build systems of accountability that saved mothers' lives.

Looking ahead, the Partnership for a Lead-Free Future was ready to clean up terrible pollutants. With 800 million children worldwide suffering from elevated blood lead levels, this initiative promised to unlock vast human potential.

Trump’s cuts to USAID threaten all these vital programs - from life-saving drugs to data-driven accountability, to ending lead poisoning. I remain extremely concerned about a resurgence in HIV/AIDS.

To prevent suffering, the world needs a seriously big injection of money.

its unfortunate, but the government (right and left) abused and corrupted this organization so deeply that there is probably no way to save it. its rotten through and through, all the way to the core. both right and left used it as a cia political propaganda machine (which did serve some purpose, albeit shady af and with some disastrous results) the left finished it off repurposing it as an ideology propaganda machine.

Those lives were only put at risk because of the failures of the political elites in their countries. Continually rescuing people creates dependency and resentment. Better to ensure that the consequences of action and inaction, and the people at fault (their own leaders), are made plain, and to ensure that the developing countries have room to create their own capabilities and capacities for self knowledge and action. Aid is patriarchy. Toxic mansplaining.

Trade preserves cultural autonomy and respect. Trade, not aid.