Why has Latin American female employment risen in the absence of growth?

Should we rethink conventional wisdom?

The great economist Claudia Goldin famously theorised a U-shape relationship between female employment and structural transformation. While female employment in manufacturing may be depressed by stigma, it rises with the expansion of female education and respectable white collar jobs. Cross-country research by Iversen and Rosenbluth corroborates the importance of services. In China too, structural transformation closed gender pay gaps.

But how do we explain Latin America? The region has been hammered by soaring inflation, relentless economic crises and persistent informality. Easterly famously described its ‘lost decades’. Productivity remains weak. Economic convergence with rich countries seems extremely unlikely. ‘Prestigious occupations’ (the kind that Goldin thought would induce female employment) are few and far between. Yet Latin America is the only world region where - in the past three decades - female employment has radically increased! Moreover, during its very brief period of commodity-induced growth, female employment mildly decelerated. What explains this paradox?

I have a suggestion! Let’s think more broadly about the opportunity costs of women remaining at home. So, on the one hand, yes, this can rise as structural transformation expands the share of occupations that are well-paid and prestigious. But as Latin America reveals, this is not the only route.

In Latin America, soaring house prices have undercut men’s ability to provide for their families single-handedly. Meanwhile, stigma and conservative social policing have weakened with secularisation. Together, these have increased the socio-economic opportunity cost of women staying at home.

My theory helps explain why Gaddis and Klasen found little empirical support for the U hypothesis.

Urbanisation and soaring house prices

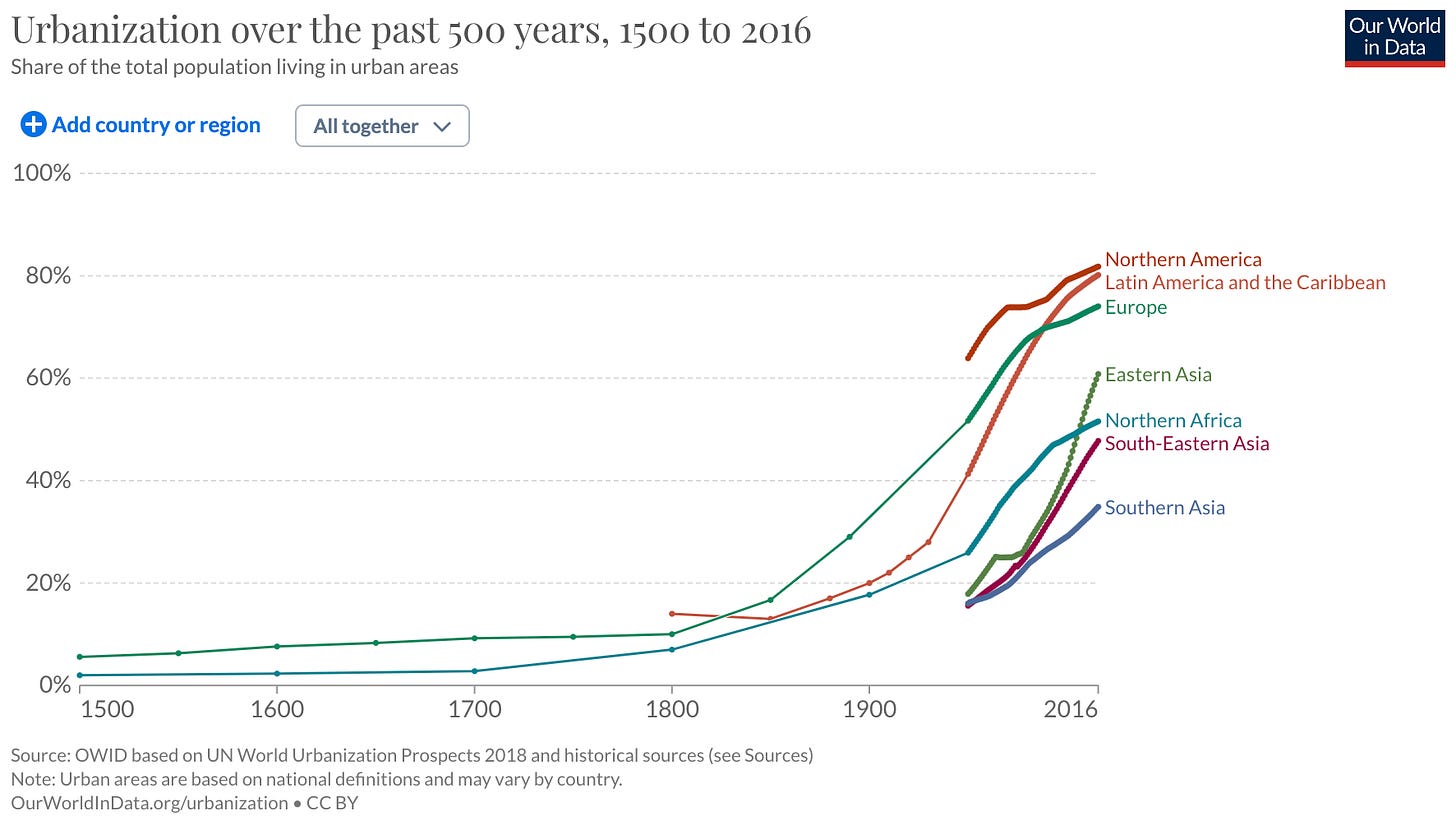

Compared to other countries with similar wealth, Latin Americans are far more likely to live in cities. When immigrants arrived in the Southern Cone circa 1900, they mostly settled in cities. Over the subsequent century, there was also rapid urbanisation. Thanks to weak constraints on female mobility, both men and women left the countryside in search of better economic opportunities.

House prices have soared, amid scarcity. Earnings, meanwhile, remain stagnant. It would take over 30 years to afford the median apartment in Buenos Aires (assuming one person works full-time and the other is part-time). As Gervasio Muñoz (president of a local tenants’ organization) explained,

“With rent increases across the board, people can’t cope because of delayed salaries and tough market rules.. So many families in Argentina don’t know where they will live because they can no longer pay rent”.

The male breadwinner is no longer tenable.

Rising individualism

Mexican parents used to be much more authoritarian and also feared social disapproval. “¿Qué va decir la gente?” (what will people think?). Rumours of impropriety would jeopardise their social standing. This motivated self-censorship and quiet conformity.

Moreover, many patriarchal ideals went unquestioned. Telenovelas gave hope to the Cinderella fantasy of an impoverished young woman falling in love with a rich man, overcoming adversity and eventually becoming happily ever after. The hegemonic narrative, shaping young women’s dreams, revolved around a male saviour. Economic dependence on a single man sometimes forestalled female friendships. Single women were often eyed with suspicion, rather than sorority.

But Latin America has become much more individualistic. This shows up in cross-country studies and also my own qualitative research. In narrating their life histories, Mexicans repeatedly prioritised economic advancement and individual autonomy. Thus even though Latin Americans typically underestimate men’s support for female employment, this is not a binding constraint, because they no longer prioritise social approval.

Cities are catalysts of social change

Social policing is most powerful in small, homogenous communities that provide mutual insurance and collectively punish deviation. If everyone bad-mouths deviants (like single mothers and working women), fear of ostracism motivates mass conformity.

But in big cities, new neighbours come and go. Communities lose their monopsonist powers to police. By mixing and mingling with diverse others, people form new friendships and learn about more egalitarian alternatives. From this rich variety of social networks, people can pick and choose more supportive friends. Seeing millions of others defying traditional expectations, others gain confidence in the possibility of change, and become emboldened. Self-expression is celebrated, and slogans of resistance are emblazoned on street murals. Thus despite Latin America’s weak structural transformation, its precocious urbanisation unleashes massive social change.

Four pivotal cultural shifts:

Recent democratisation, a culture of resistance, and human rights

The demise of marriage

More North American media.

The Church has lost its grip. In the latest Latinobarometer poll, 60% of Argentinians and Chileans said they were not religious.

Marriage, meanwhile, has plummeted. Couples increasingly cohabitate, and these unions are often unstable. When relationships sour, single mothers are left in the lurch, all on their own. Evidence from the US and Europe suggests that the demise of marriage can increase female employment. As women lose faith in men, they seek economic security from the market.

Media consumption has also diversified. US influence increased with cable TV, online streaming and social media. When I went to a women’s bookclub in Puebla, they were actually most excited to discuss their favourite shows on Netflix, such as the Marvellous Ms Maisel. Nearly 90% of Argentinians now have smart phones. Fantasies about being saved by Prince Charming are being displaced by stories of strong independent women. Rather than seeing men as saviours, Latin America’s young feminists are increasingly decrying machismo. Sexist violence and infidelity are no longer normalised. Instead, they are subjects of contempt (as shown by David Rozado’s media analysis below).

TLDR

Latin America presents a conundrum. Female employment has soared, despite economic stagnation. These two facts challenge conventional wisdom.

Rather than dropping a little data, omitting Latin America from our sample, let’s refine our theory.

I suggest we consider the social and economic opportunity costs of women remaining at home. In MENA and South Asia, female paid work in the public sphere jeopardises men’s honour. Female seclusion enhances social respectability. In terms of culture, the opportunity cost is actually low. In Europe and the US, by contrast, skill-biased technological change boosted prestigious white collar occupations. As graduate salaries soar, opportunity costs become even higher.

But Latin America suggests that opportunity costs may also increase with hyper-inflation and individualism. If house prices outpace male earnings, even a tiny increment in earnings may be deemed desirable. Stigma is also malleable; it wanes as societies become more urban, secular and individualistic.

So although Latin America lacks prestigious jobs, women still want to work.

I think you need more time series data here.