Why has Female Employment Fallen in China?

China’s female labour force participation has fallen. Why might this be?

This Substack explores seven contending hypotheses:

Stigmatisation of female employment

State-owned enterprises closed and shed labour

Unaffordable childcare, due to government cuts

Prosperity. As male wages rise, women step back

Discrimination

Stagnant labour productivity growth in low/medium tech and services

Low household consumption

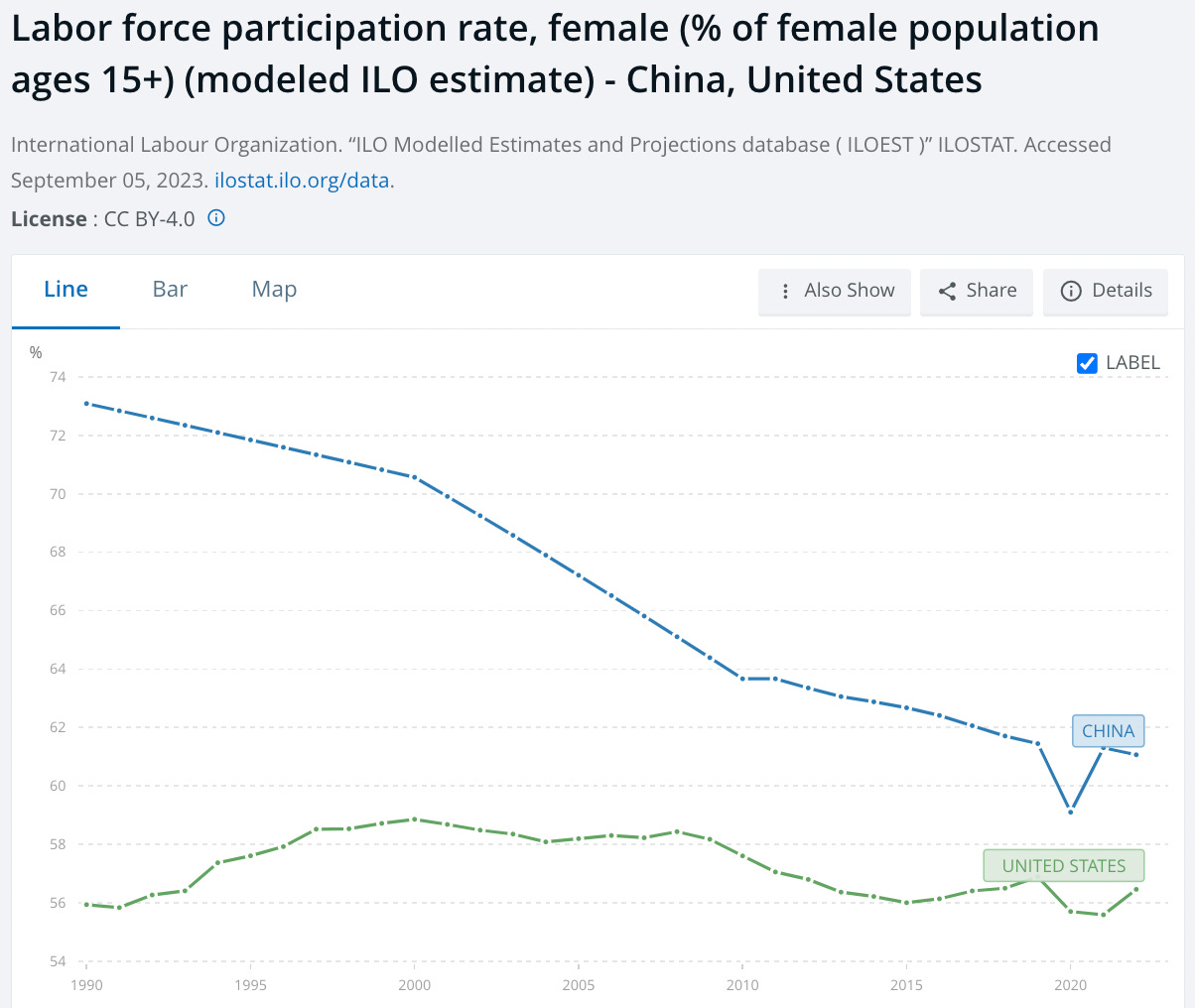

Chinese FLFP has fallen

Here’s the downward trend.

Stigma?

In South Asia, female employment has fallen because mechanised agriculture has shed labour while earnings in other industries are too low to outweigh cultural preferences for housewives.

This is not true for China.

In China, female employment is extremely high and broadly accepted. Most Chinese people say that wives should contribute financially. Working motherhood is supported by a large majority. Daughters display filial piety by providing for elderly parents - just like sons.

Economic success (not Confucian conformity) defines social prestige. Chinese women want to work. This holds right across the class spectrum - from precarious migrants to university graduates. Husbands are typically supportive. Chinese sons of working mothers tend to endorse gender equality, welcome their wife’s contributions and do more housework.

Chinese patriarchy is best encapsulated in this post on “Little Red Book” (the equivalent of instagram). A guy says,

“I want to marry a semi-feminist: someone who works, pay the bills, but is still a very kind, caring, self-sacrificial good wife” [translated by my friend from southwest China].

Female employment is perfectly acceptable!

Closure of state-owned enterprises?

Over the 1990s, China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) retrenched labour. When output contracted, SOEs shed women or else paid them far less.

But over the past 30 years, China’s booming economy has generated more jobs. This isn’t a simple story of falling demand.

Unaffordable childcare?

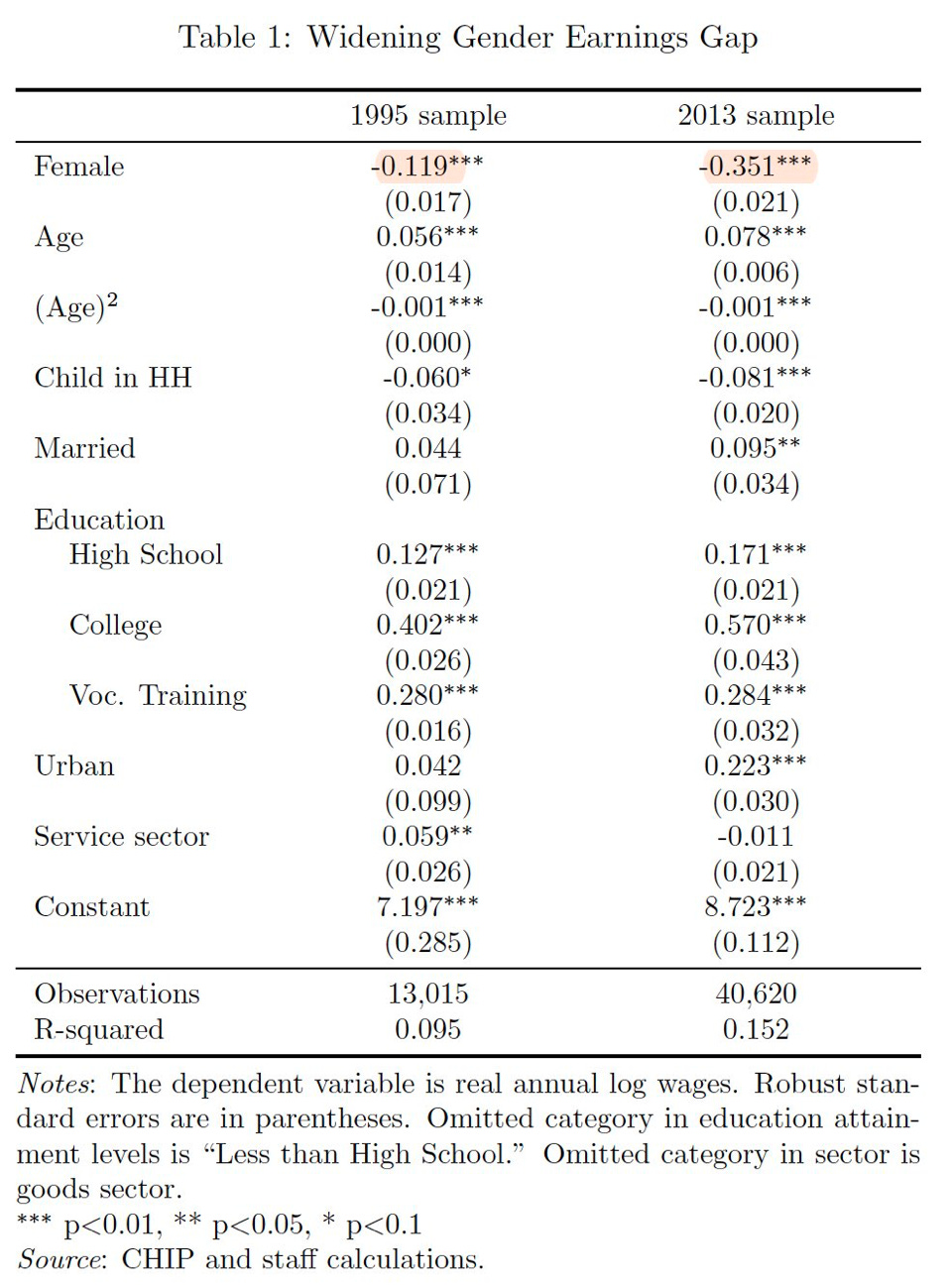

In 1995, Chinese women worked long hours regardless of whether they had children. By 2013, mothers were stepping back.

Unaffordable childcare is a major constraint for working-class women worldwide. In China, this has been compounded by state-cutbacks and closures of kindergartens. But is this the primary driver?

Childcare providers are actually viewed by Chinese mothers with deep distrust. Scandals about infant milk formula and children’s maltreatment continue to circulate. Constant anxiety and worry are encapsulated in the the now common term ‘jiaolv’ .

Distrust is a direct consequence of totalitarianism. Consumer protection is virtually absent. Property is insecure, vulnerable to destruction. Cronies are protected; the precarious masses venture on a precipice. Legal rights are poorly enforced, claimants are overwhelmingly dissatisfied.

Surveillance has intensified; social unrest is sternly punished. Mass mobilisation has virtually has waned. By crushing collective litigation, totalitarianism sustains impunity for myriad abuses.

Given distrust, Chinese families would not necessarily use kindergartens, even if they were more affordable. Instead, many would rather rely on grandparents, but this is difficult for rural-urban migrants.

Prosperity

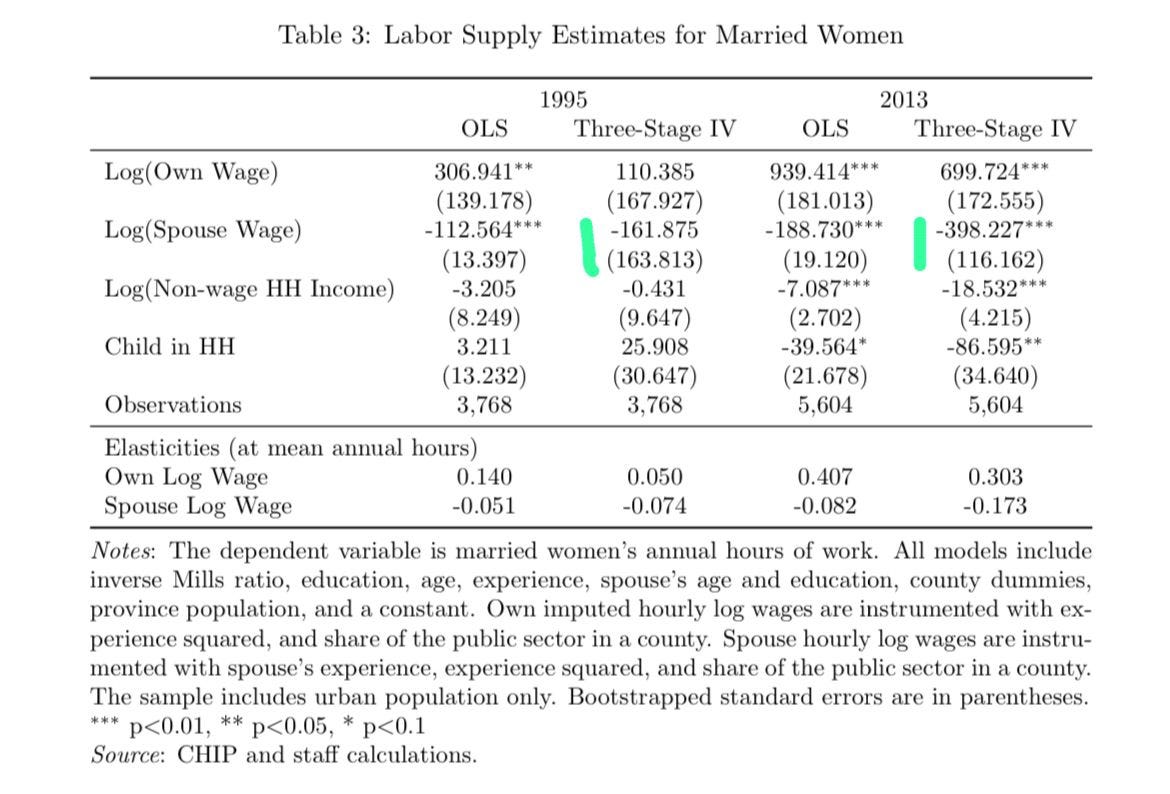

When wages rise, people work longer hours. But household labour supply is gendered. Chinese women now work fewer hours if their husbands earn more - this interaction actually increased between 1995 to 2013.

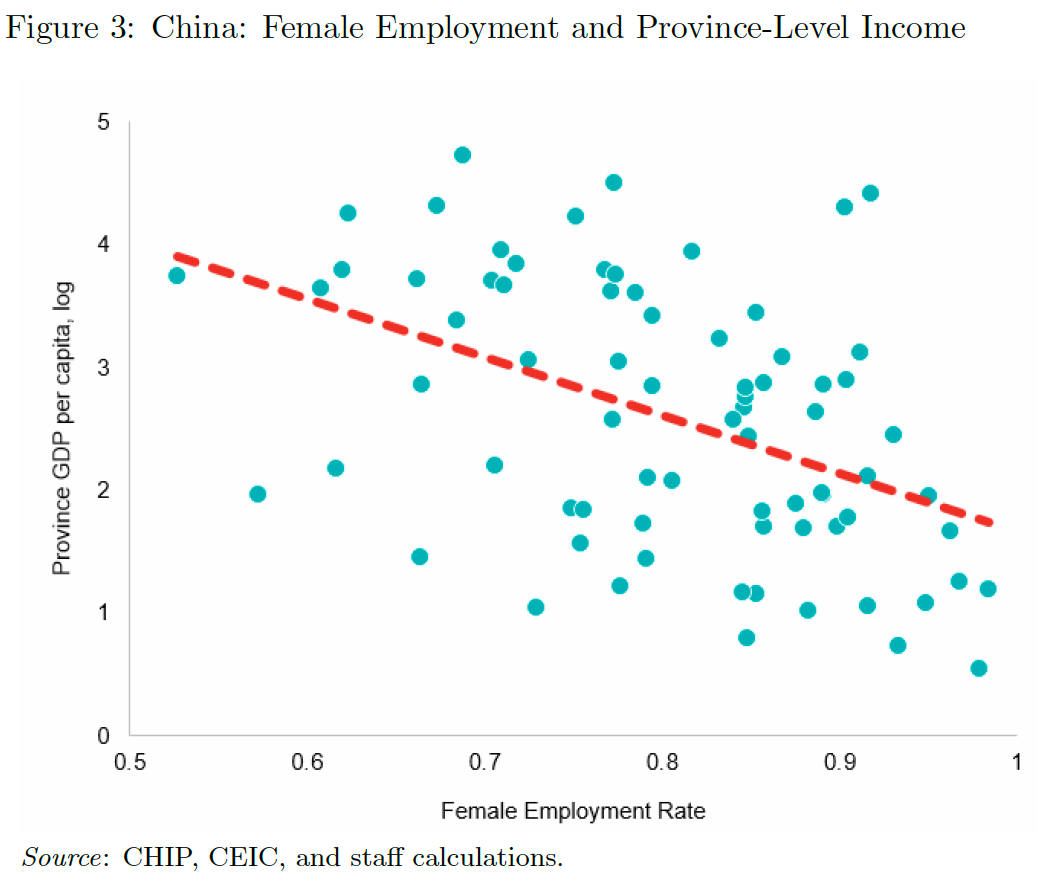

Chinese female employment is thus lower in provinces that are wealthier.

This is not evidence of patriarchal resurgence. China’s rate of female employment was extremely high. It remains much higher than the US.

Rather than exhausting themselves at the coal face, burning the candle at both ends, Chinese women are increasingly caring for their families.

Sexist Discrimination

The gender gap in earnings gap has actually increased. In 2013, Chinese women earnt 35% less than men.

Sex discrimination runs rampant. According to a 2017 official survey, 54% of women said interviewers had been asked about marriage and childbearing. Chinese migrants tell me their female peers anticipate discrimination, but feel powerless to resist.

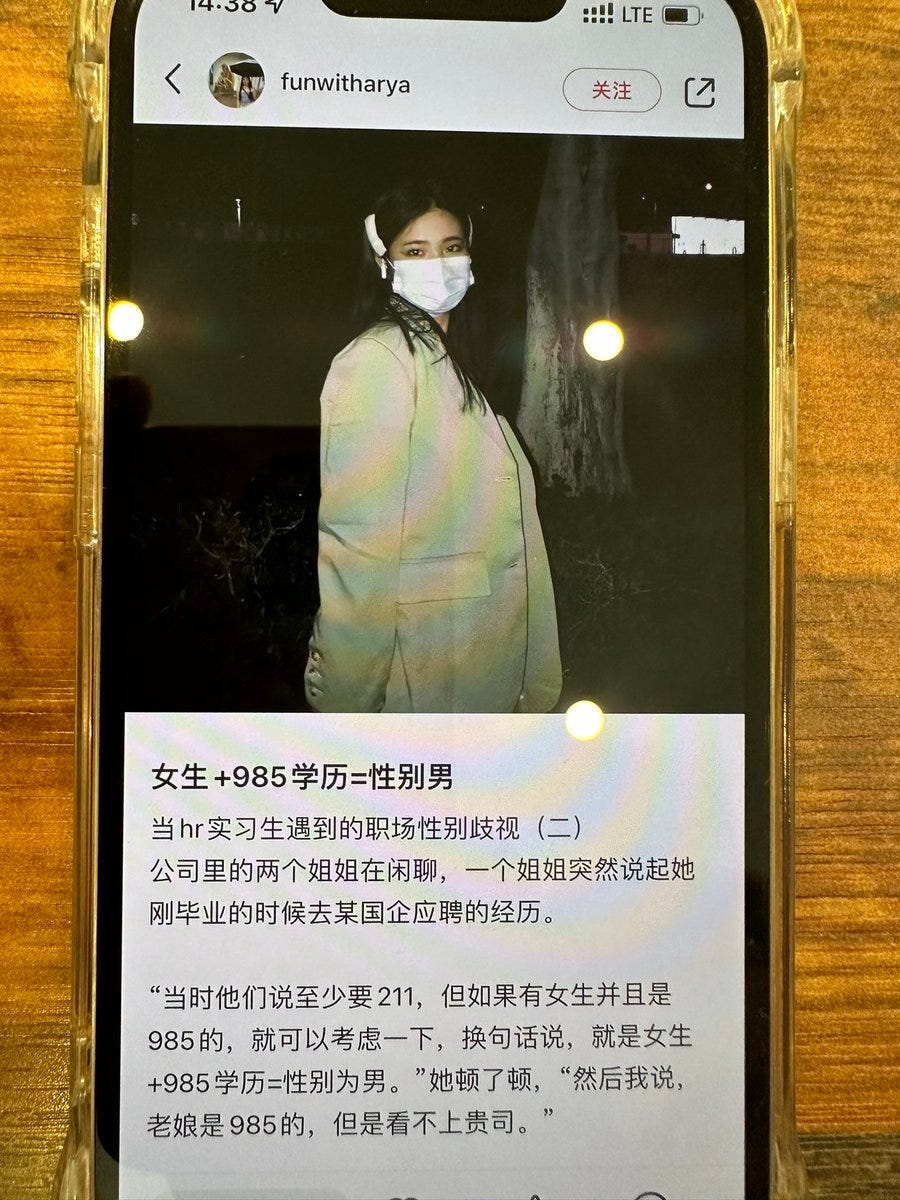

On “Little Red Book”, women vent their frustrations:

“Female + 985 = male” remarks one user. This means a woman with qualifications from a prestigious university is worth the same as a mediocre man.

At university recruitment fairs, companies openly tell women, “Don’t bother applying”.

China’s labour market is also hyper mobile. Women change jobs more frequently than men, every 1.6 years compared to 2.3. This may indicate higher female dissatisfaction.

While Chinese middle-class women resent discrimination, many feel powerless to resist. Chinese migrants tell me this isn’t even an option. Patriarchal authoritarianism has institutionalised despondency.

Sexism may sap labour market commitment. Married mothers re-evaluate. Why slave away for a company that refuses to recognise your worth?

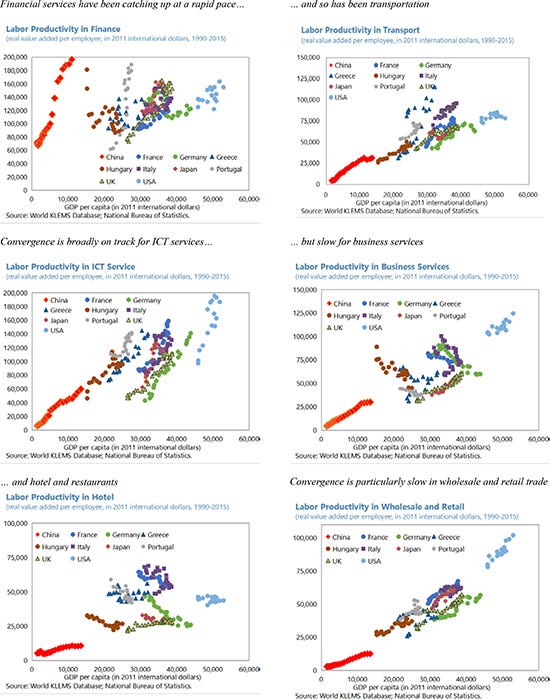

Declining labour productivity in services and low/medium-tech

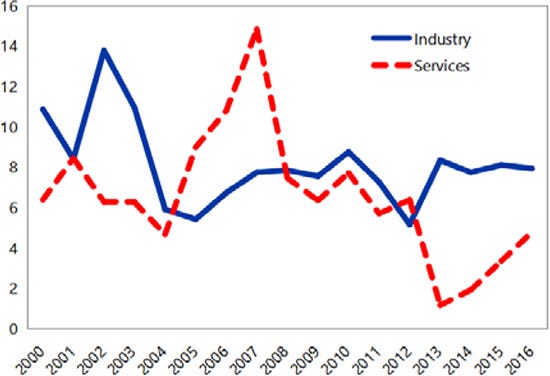

Sexist discrimination must be contextualised alongside labour productivity growth.

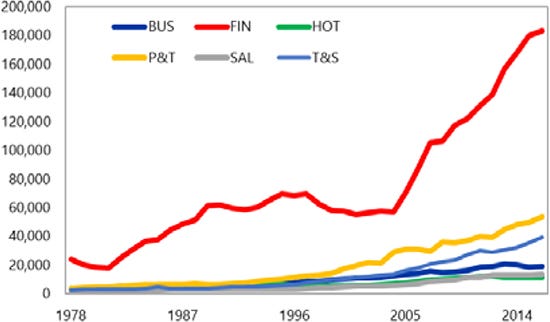

45% of Chinese working women are in services. Wholesale and retail trade comprises the largest employment share of market services, but productivity is very low. Retail may be especially attractive to Chinese women, as it is easier to juggle with child and elderly care.

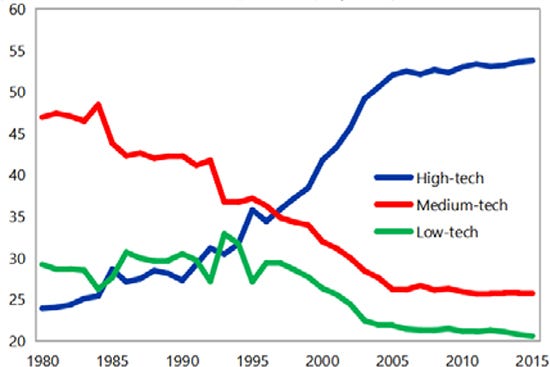

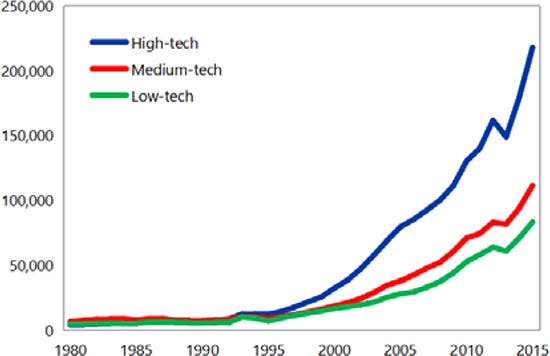

Labour productivity growth has also fallen in low/medium-tech. This suppresses labour demand and wage growth.

Low household consumption

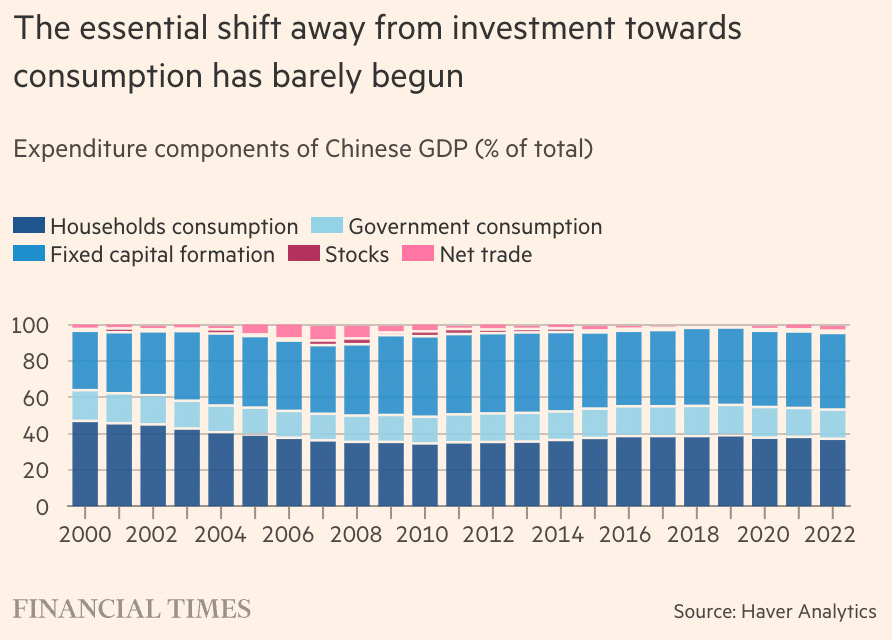

Household consumption (as a share of GDP) is also low and stagnant. China remains caught in an economic model of high savings rate and investment, which is running into diminishing returns.

Weak domestic demand for goods and services depresses employment generation and wage growth.

Why has female employment fallen in China?

Weak household consumption alongside stagnating labour productivity growth in retail trade and low/medium tech have likely suppressed labour demand and wage growth.

The labour market thus presents several options:

Paltry wages and harsh conditions in low/medium tech and retail trade;

Job queues in sectors where labour productivity is rising.

Meanwhile, male workers can credibly commit to working extremely longer hours. Employers take their pick and need not hire women.

Gender pay gaps aren’t merely a function of economics. Patriarchal authoritarianism maintains impunity. Women vent frustrations on social media, but seldom organise against sexist companies or oppressive government. Recruiters continue to discriminate in broad daylight.

So, if Chinese husbands can provide economic security, women sometimes step back. China’s historically high female employment has thus fallen.

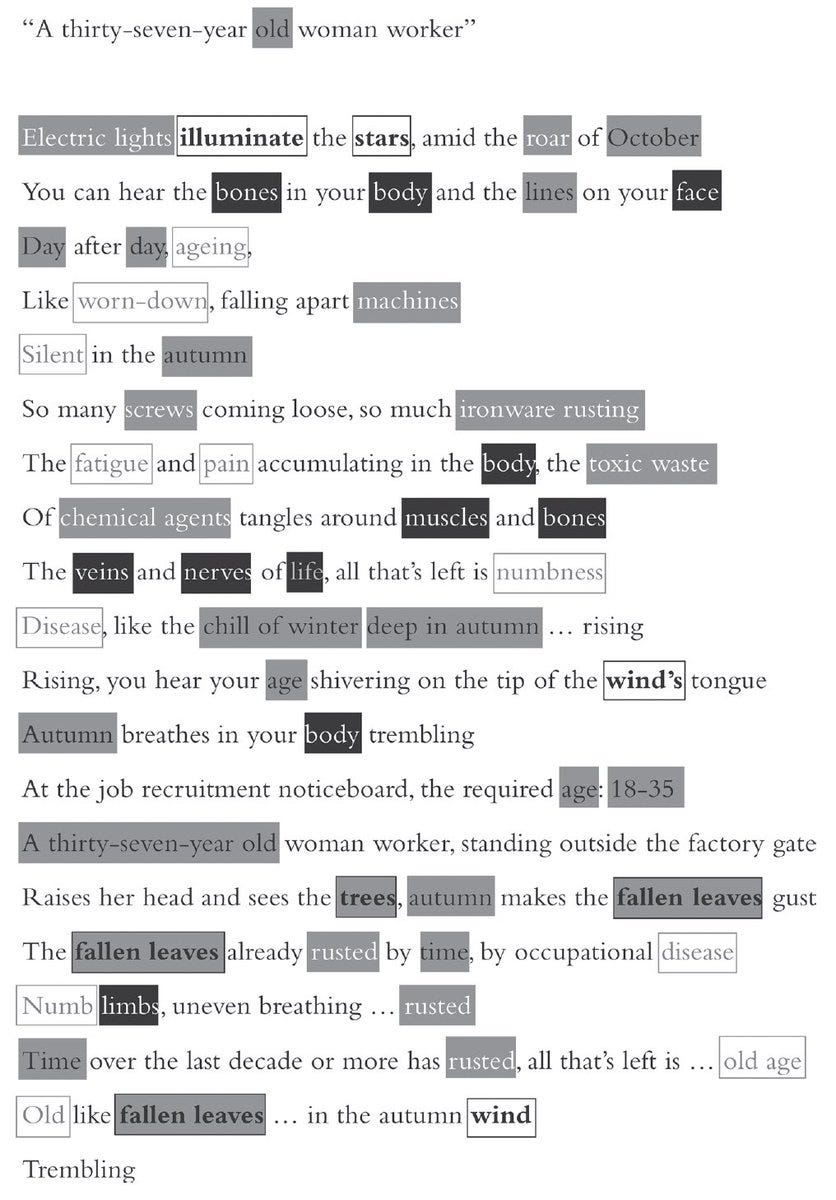

Migrant worker poet Zheng Xiaoqiong viscerally encapsulates this brutal rejection. Having toiled for several decades, her body breaking with fatigue and chemical pollutants - a factory worker learns she is unwanted.