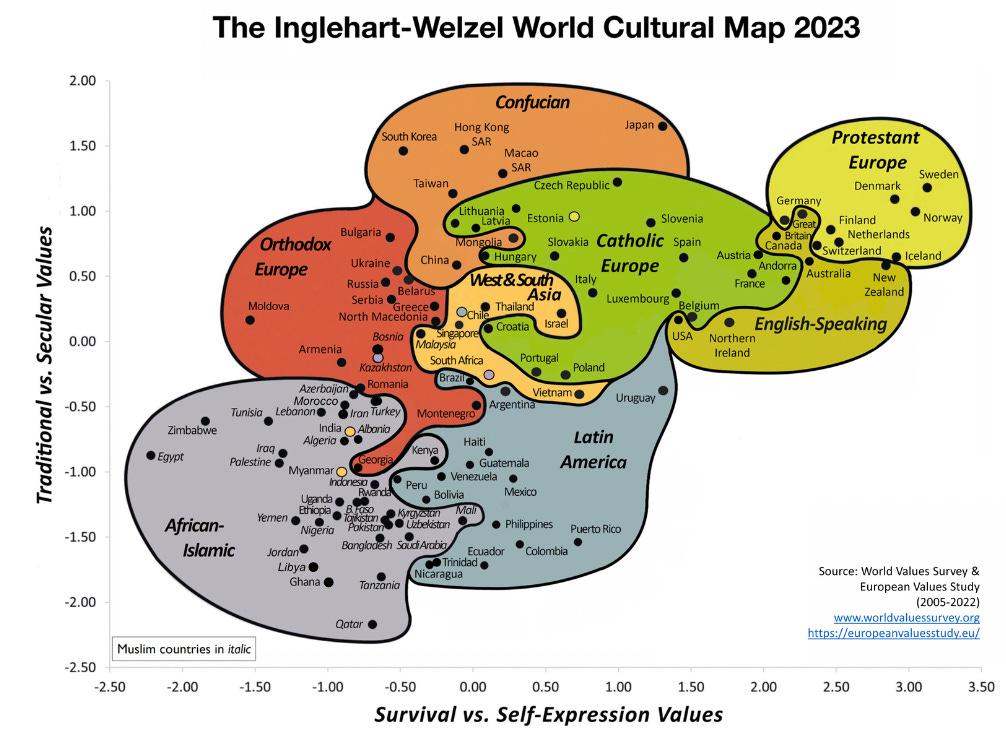

In the West economic development spawned individualism and the spirit of ‘68. Modernisation theorists predicted that growth would deliver liberalism worldwide. Inglehart and Welzel argued that post-industrial societies would champion self-expression. But in fact, this has not transpired. Many prosperous places - like Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and South Korea - remain quite conservative. India’s economic growth has not delivered secularism, but Hindu nationalism.

Why explains this global cultural divergence?

I have a theory:

Cultural change occurs when bold rebels stick their necks out, champion some radical alternative, and successfully encourage wider defiance.

In close-knit, collectivist societies, people care intensely about wider social approval, and tend to follow the herd. This suppresses individualism.

Cultural tightness is much higher in societies where:

Agriculture was extremely labour-intensive and required strong inter-dependence (e.g. rice or Andean potatoes), and/or

Intensive kinship meant that commerce, cooperation and marriages were all rooted in a close-knit, endogamous community (tribe, clan or jati);

Authoritarian governance represses dissent and reinforces despondency.

In culturally tight societies (with labour-intensive agriculture or strong kinship intensity), then even as families grow richer, they still care for social approval. This suppresses individual resistance.

Now let me present empirical evidence in support of all the above.

Warning: this Substack features graphic (but relevant) male and female nudity.

It’s also LONG. But this is a theory about the entire world! So please bear with me.

In the West, economic development spawned individualism

In North America and Europe, university enrolment soared over the 20th century. Leaving behind their families, university students enjoyed newfound fraternity and freedoms. Overturning gerontocracy, the 1960s Counter-Culture explored their own ideas of social justice. Protests erupted against the Vietnam War; while Rock and Roll music celebrated a spirit of rebellion; and people got loose on recreational drugs.

This culture of youthful resistance was enabled by job-creating economic growth, urbanisation, democratisation, and universities. Students had the time, fraternity, and economic autonomy to think for themselves and organise for alternatives.

In Zurich, I interviewed a leading Swiss activist (now elderly). For her cohort, ‘68 marked a new era of secularism, liberal tolerance, individual rights, independent critique, and a growing belief that change was possible through mass mobilisation.

Feminist activists shouted, ‘my body, my rights’. In consciousness raising groups, marches and art collectives, they rebelled against patriarchal expectations. They demanded autonomy. Let me share a few illustrative pictures from a current exhibition at Tate Britain: “Women in Revolt”.

Through history, patriarchy has been normalised through cultural celebrations. Marriage and motherhood were praised as women’s primary roles. While care-giving can be incredibly fulfilling, normative expectations can also make women feel guilty for pursuing other pursuits, like leisure or careers. Worldwide, female labour force participation is lower in countries where motherhood is seen as primary.

1970s British activists broke taboos by highlighting maternal drudgery. Maureen Scott’s (1970) “Mother and Child at Breaking Point” highlights tedium.

“Women: don’t break down, break out” - shouted Shrew Magazine (formed by the London Women's Liberation Workshop).

If you look at posters and placards from the Women’s March in London, you see strong demands for female autonomy. Women wanted ‘liberation’, contraception and abortion. They wanted to control their own bodies.

Penny Slinger designed a series of photos, which parody the wedding ritual by suggesting that women are treated as dolls. You may find it vulgar and graphic, but back then marital rape was perfectly legal. Feminists were saying ‘no’.

The West was patriarchal and homophobic. Both ideologies were increasingly criticised. Refusing to be silent or ashamed, gays came out of the closet.

Through protests and paintings, Western feminists challenged normative expectations of marriage and motherhood. Rather than putting family first, they demanded autonomy and self-fulfilment. These protests were distinctly individualist.

But the West was not culturally homogenous. Liberals’ demands for gender and racial equality triggered a counter-movement. Across America’s Bible Belt, close-knit communities demanded respect for the flag and the cross. They cheered for Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump, who promised to uphold white Christian nationalism.

Any theory of individualism must explain this sub-national heterogeneity.

Rule-breakers and rule-makers

If you walk outside and do something weird, will anyone mind? India’s panchayats would certainly express disapproval and punish deviation. Such cultures are ‘tight’. The rules are known, conformity is widespread and subversion is abhorred. But head to São Paulo and no one will care. ‘Loose’ cultures like these are relatively tolerant and open-minded. There’s plenty of scope for self-expression.

Professor Michele Gelfand and co-authors’ international survey (spanning 33 countries across 5 continents) reveals a spectrum of 'tight and loose cultures. People in tight cultures show greater self-control, conscientiousness, less littering, lower crime, more synchrony, stronger prejudice against outsiders, low immigration, low ethnic diversity, and more restrictions on public speech. Loose cultures are typically more open, tolerant, creative and over-weight.

Neither extreme is superior, these are just descriptively different cultures.

Within the US, there’s great cultural heterogeneity. Southern states have far higher rates of corporal punishment, executions and alcohol restrictions. In Texas in 2011, 28,000 school students were paddled or spanked. Alabama still criminalises the sale of sex toys. Tight states like these strongly opposed the Equal Rights Amendment.

What explains this variation?

Norm adherence isn’t just a function of self-regulation. Gelfand also emphasises institutions. Tight cultures tend to have more police per capita and security personnel. In Singapore, there are harsh punishments for littering, drug possession and even importing chewing gum. In some Chinese classrooms, webcams broadcast children’s behaviour, relaying footage to parents and school officials.

Pro-sociality may be also enforced through group rituals, like singing. A Chinese child’s school day may start with carefully coordinated group exercise. Synchronisation promotes unity and cooperation.

Why do some societies strictly police norms, while others turn a blind eye? Why are demands for conformity so much higher in the US South?

Cultural tightness is stronger in places where crops were labour-intensive

Our ancestors used to farm a rich variety of crops. Some were very labour intensive, requiring neighbourly cooperation.

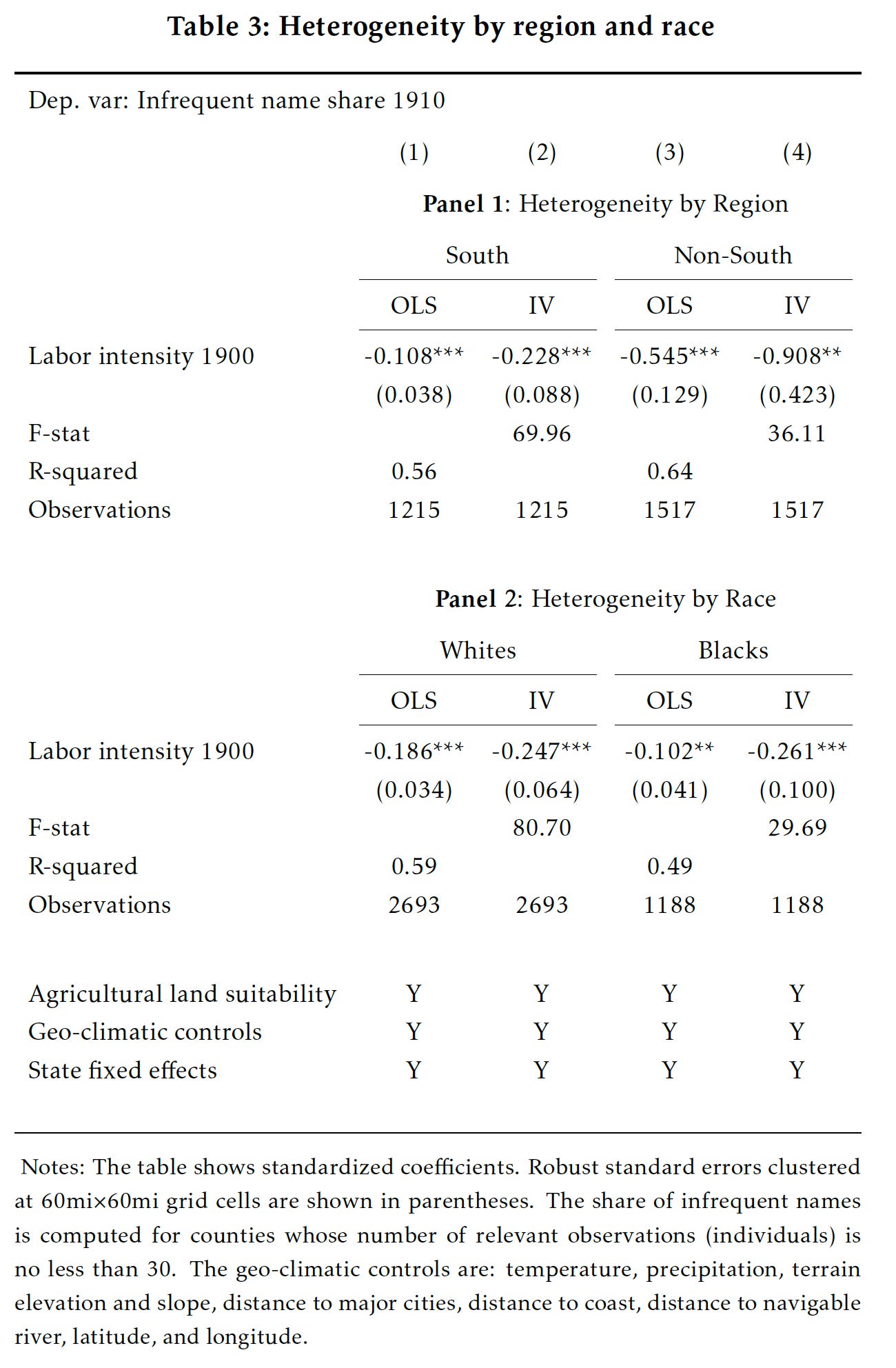

A phenomenal new paper by Martin Fiszbein, Yeonha Jung and Dietrich Vollrath finds that in U.S. counties with labour-intensive crops, parents were more likely to give their children names that were common. This may indicate a desire for conformity. By contrast, in areas where farmers could be more self-sufficient, they chose names that were more individualistic. And when exogenous shifts propelled farmers into economic autonomy, they became even more self-expressive.

Potatoes required three times the labour as wheat. Cotton needed seven times as much.

Crops in the U.S. South were exceptionally labour intensive. There’s also significant within-state variation - which the authors exploit to disentangle the effects of agriculture and institutions.

Agricultural labour intensity is strongly correlated with individualism. This holds in both the north and south, for both white and black Americans.

But what about endogeneity? Maybe individualists settled and survived in places where they could farm independently? To examine how farming shaped culture, Fiszbein and colleagues consider two agricultural shocks: mechanisation and pests.

Mechanisation

Mechanisation affected the amount of labour each crop required. Hand-cultivating an acre of wheat required 61 hours. Machines meant it could be done in 3. But the precise shifts in labour requirements varied by crop type. Cotton actually remained very labour intensive. In places where mechanisation increased crops’ labour intensity, names became less individualistic.

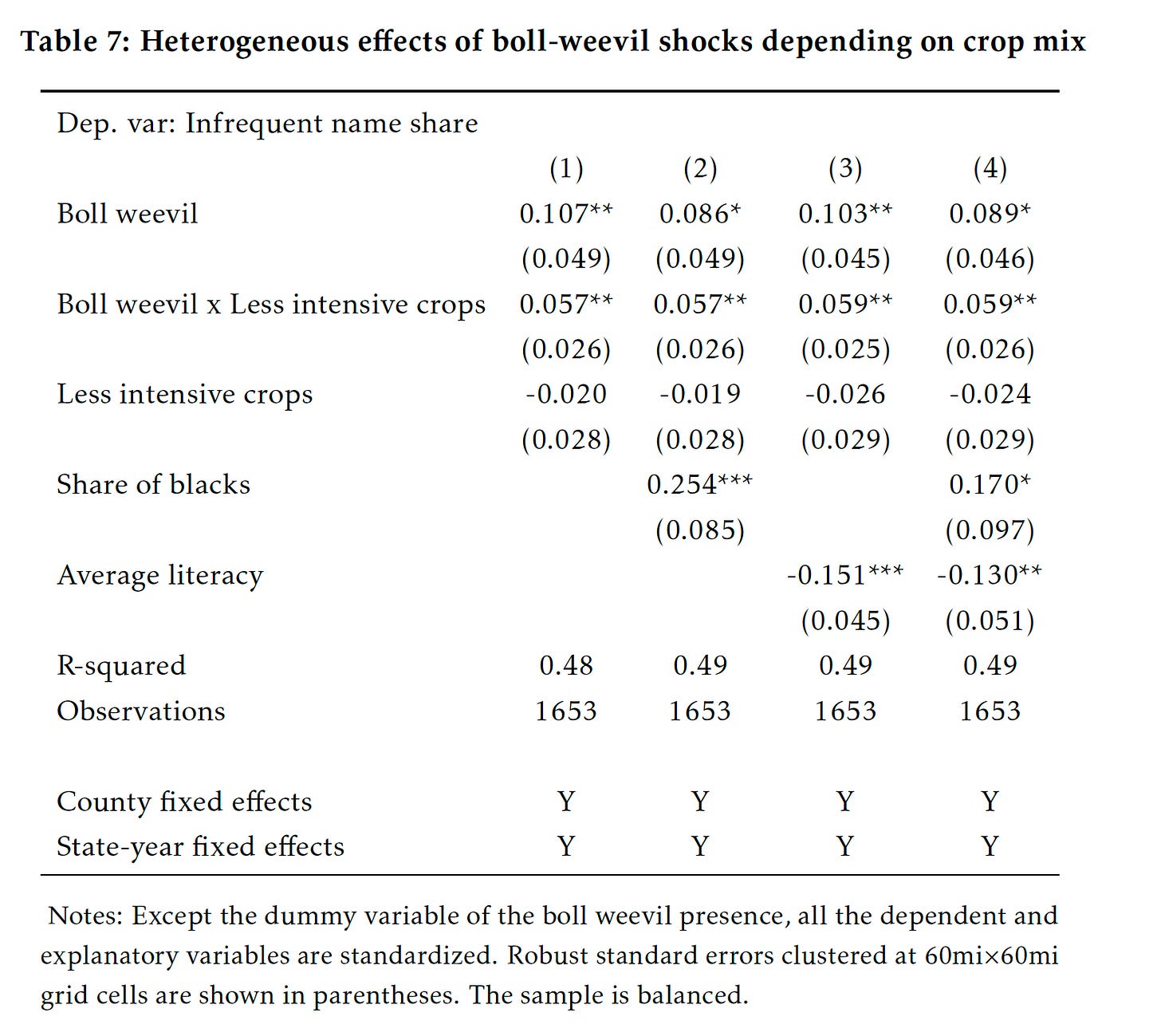

The boll weevil

Cotton was extremely labour intensive. But after the arrival of the boll weevil insect (1890s-1930s), cotton was decimated and farmers were forced to adopt alternatives. This exogenous shift in labour intensity led to an increase in individualism across the South. Farmers who adopted low labour intensity crops, like wheat or rye, became much more individualistic.

Long-Run Cultural Effects

In counties with high labour intensity in 1900, people are now more likely to search for the term ‘common’ (rather than ‘unique’). They’re also more likely to prefer team sports, support redistributive policies, and vote at high rates. These are all indicators of strong community bonds.

Cultural tightness

Economic interdependence seems to breed cultural conformity and collectivism. These are both examples of what Michele Gelfand calls ‘cultural tightness’. People in tight cultures show more synchrony, stronger prejudice against outsiders and more restrictions on public speech. Outraged by deviants, they tend to impose harsh punishments. As mentioned, in Alabama, for example, it’s illegal to possess, produce or distribute a sex toy. Fiszbein et al do not consider cultural tightness, but it does seem correlated with 19th century labour intensity.

Did agrarian interdependence sow the seeds of cultural tightness, worldwide?

Globally, cultural tightness seems more common in places where farming was once extremely labour intensive and necessarily interdependent. Wet paddy rice required immense coordination. Thomas Talhelm argues that this encouraged East Asian collectivism. Students from rice-growing regions contribute more to public goods and harshly punish free-riders.

I was initially sceptical of the rice theory of culture. What about Confucianism and institutions? Fiszbein et al’s paper enables us to disentangle the two. Even under totally different, American institutions, agrarian interdependence nurtures conformity.

Chuño may provide another fertile area of study. This is a freeze-dried potato made by Quecha and Aymara communities in the Andean Altiplano. After harvesting, potatoes are laid out, frozen over night, then exposed to intense sunlight.

This process is extremely laborious. High demand for labour may help explain why nearly all rural Peruvian women work. It may also explain why skeletons from 500 CE showed higher wear and tear if they were from (chuño-growing) highlands rather than lowland plains - indicating labour intensity.

Heightened labour intensity helps explain indigenous institutions. Highland society traditionally comprised ayllu communities with two kinds of reciprocal labour: prestamanos (borrowed hands for harvest) and minga (communal work, like irrigation). Minga comes from the Quechua word minccacuni: ‘asking for help by promising something’. Ayni is another word for reciprocity: ‘today for you, tomorrow for me’. Labour exchange sustained kinship ties of cooperation, fraternity and loyalty.

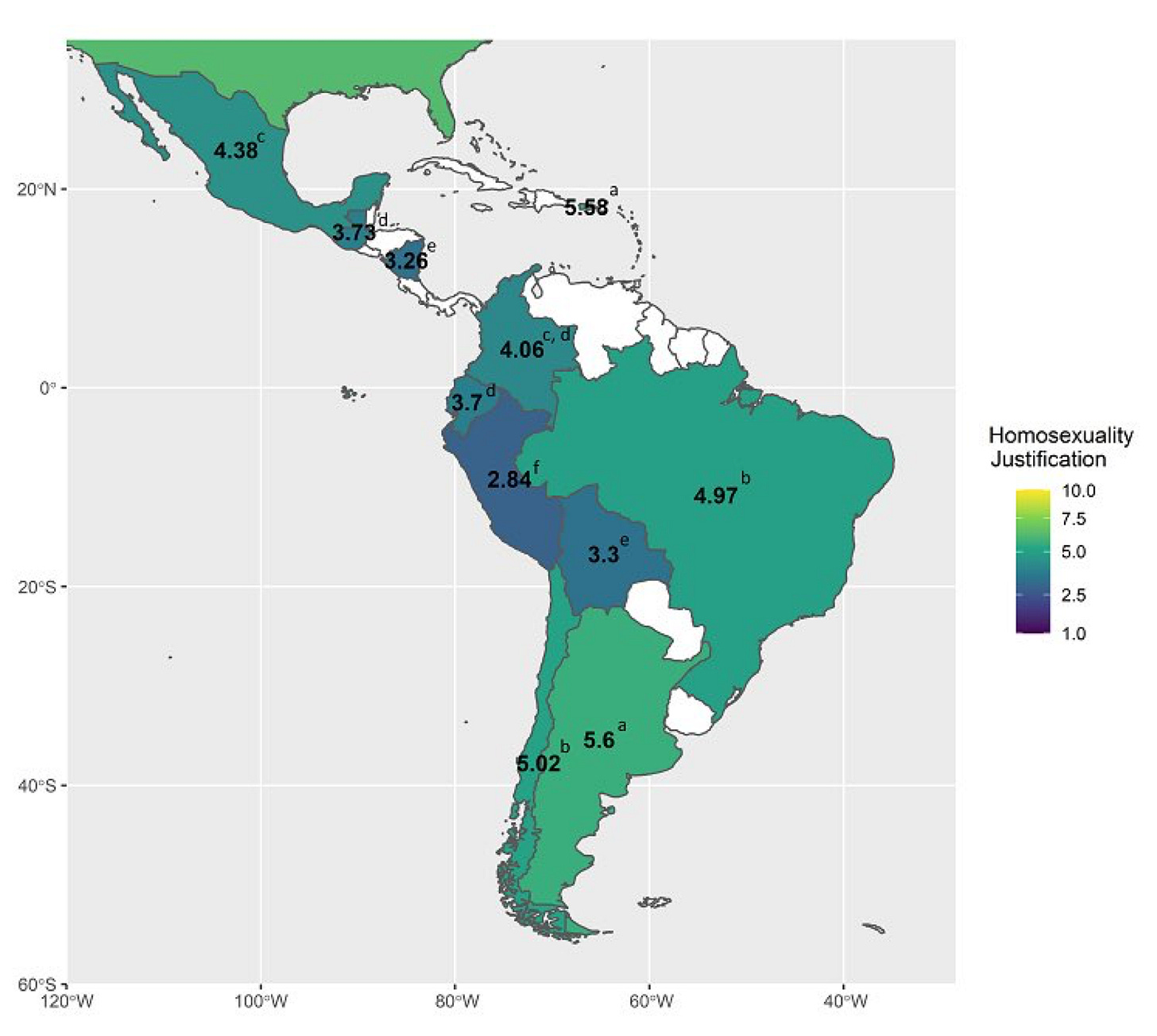

Today, Peru scores as very collectivist. Homophobia is also extremely high (indicating little tolerance of individual self-expression).

Geography is not destiny!

Over the past two millennia, Eurasia underwent an important cultural divergence.

Endogamy solidified in South Asia, Central Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa.

Around 1600 years ago, upper caste populations in north India became much more endogamous - marrying extended relatives. That’s when the powerful Gupta Empire enforced moral strictures, under the age of Vedic Brahminism.

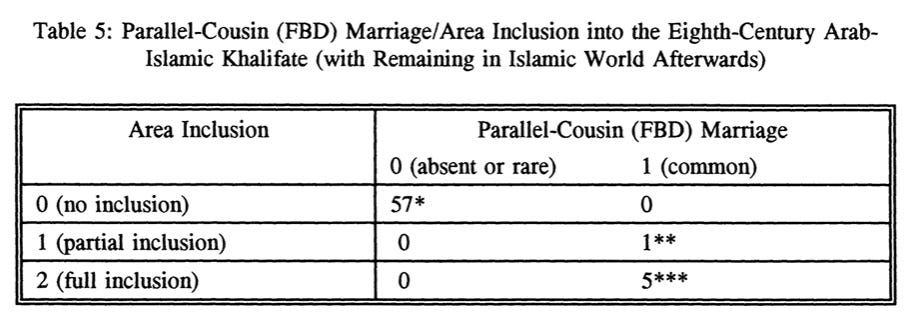

After Arab armies conquered territories across the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia, communities gradually converted to Islam. They also adopted Arab culture, like cousin marriage. Parallel cousin marriage is highest in areas once under the Caliphate and still Muslim.

In Western Europe, by contrast, the Church promoted nuclear families.

From 300-1300 CE, the Roman Catholic Church and Carolingian Empire stamped out cousin marriage and polygamy. English peasants disregarded lineage and rarely exchanged work with extended kin. Young men and women often worked in service until they saved enough to establish nuclear households. Precociously deep wage labour markets and urbanisation accelerated exogamy.

Back then, Europe was still extremely religious, conservative and patriarchal. But people were less orientated around the family. Merchants could develop broader associations and network more widely.

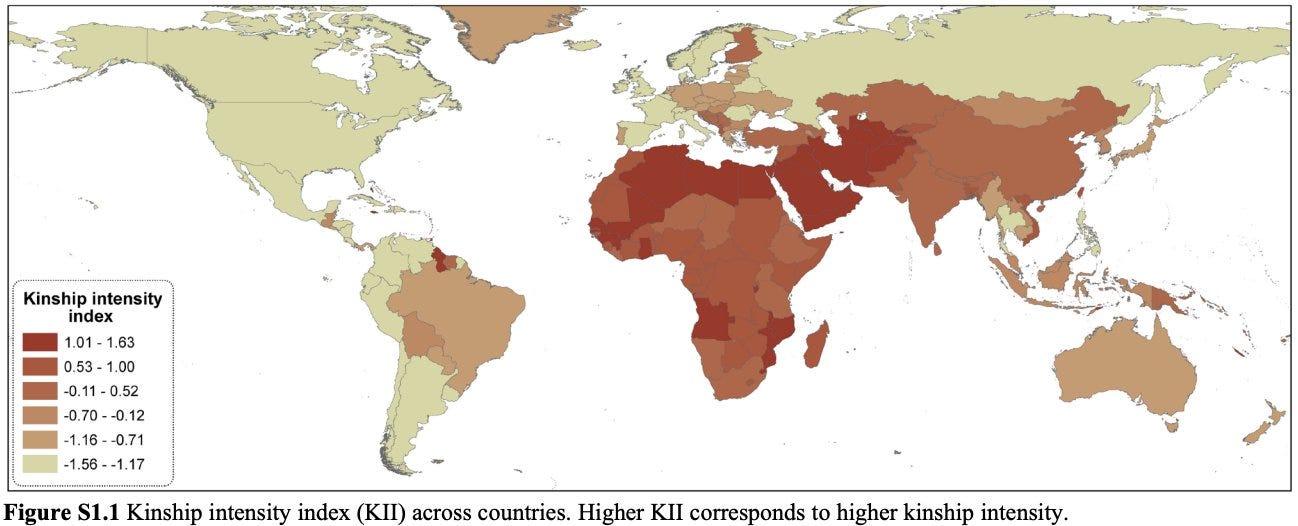

The map below - from Schulz and colleagues - maps kinship intensity worldwide.

In his book, “The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous”, Joe Henrich emphasises the Western Church and Protestant Reformation.

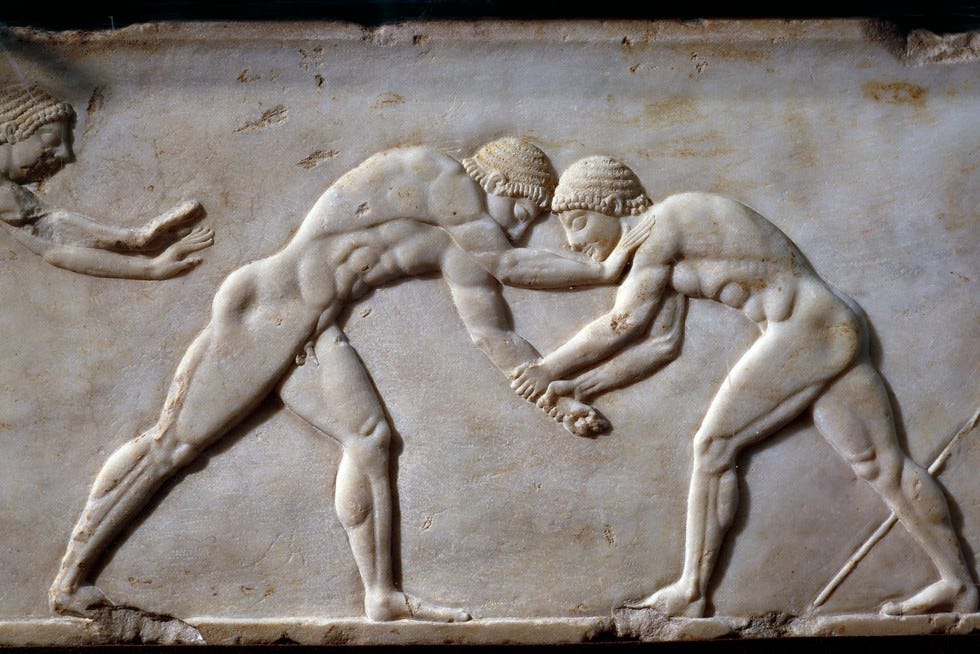

But this nuclearisation may have been enabled by prior geography. Europeans mostly grew wheat, which has very low labour intensity. While the wheat-growing Ancient Greeks were extremely patriarchal, they were also quite individualistic, e.g.:

A strong culture of philosophical debate, challenging established wisdom.

Olympic competitions were primarily between individuals.

Kinship intensity enables social policing

Strong kinship intensity keeps commerce and cooperation rooted around the family. This enables strong social policing and concern for wider approval.

Arabs continue to rely on wasta. Social connections are necessary to access jobs, secure permits, avoid trickery, and resolve conflicts. Even middle-class, professional Jordanians acquire social insurance from kin. Loyalty is also culturally esteemed: girls are encouraged to put family first, above narrow self-interest.

Caste remains imperative in India. Cities (especially the smaller ones) are rife with caste-based residential segregation. People remain dependent on close-knit networks, which maintain strict surveillance (messaging via Whatsapp).

“Everything is so dependent on social relations: contacts, helping each other, solving problems, capitalism is so entrenched in social networks, these are built through reciprocation of favours, attending each other’s events and buying gifts. We still need that community. This is why we have all these annoying aunties when you are getting harassed” – Pooja, lecturer from Haryana.

In India there is a lot of fear and anxiety. If you rock the boat, you’ll be poor. If you speak out you’ll be a social outcaste. They don’t want to face the consequences of going against the grain” – Aanya, professional in Mumbai.

Uyen Ninh (a hilarious Vietnamese immigrant in Germany) has an excellent video, where she contrasts collectivist Vietnam with more individualist Germany:

“[In Vietnam] you have to be as thin as possible. If you look like me, a bit chubby, you’re going to be called ‘béo’ [fat] by everybody. Everyone makes sure to let me know that I’m fat, even people that I don’t even know come up to my face and tell me that I’m very fat and must stop eating”

“In Germany, I feel like women doesn’t have to be finding a partner, giving birth to a son, and then devote her time to raising them. I remember the first time a woman told me she wanted to remain childfree. And that conversation BLEW MY MIND. I didn’t know it was possible.

Now I’m 28 and have a fiancé, sometimes we talk about whether we should have a child. It’s such a reassuring feeling that whatever I choose it’s going to be okay”.

Kinship intensity also seems to encourage religiosity

I suggest this is for 3 reasons:

Cultural tightness may foster a desire for moralising supernatural punishment, to police ‘bad behaviour’. Punitive gods substitute for strong institutions: they preserve order and lower cheating.

If close-knit communities are deeply religious, sacrosanct teachings may go unquestioned.

Members may conform with religious prescriptions to gain respectability. When Pakistani and Malaysian preachers emphasise ‘Hell’, they are implicitly threatening earthly ostracism.

Structural transformation and cultural liberalisation

When people are less dependent on their neighbours’ support and approval, they do become much more self-expressive. Fiszbein and colleagues focus on American farming, but their evidence is consistent with a wider body of evidence on structural transformation and cultural change.

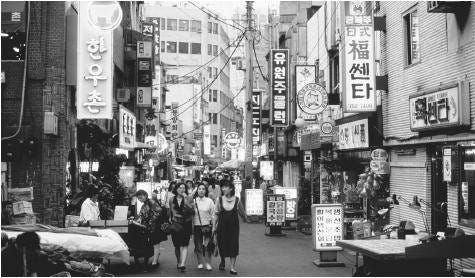

Koreans may be ‘culturally tight’, but this was weakened by rapid economic growth. As young adults moved to the cities and earnt independent wages, they increasingly dated before marriage, chose their own partners, then established their own households. They liberated themselves from parental control.

But even at the exact same level of wealth, Koreans are still far more conformist and collectivist than people in North Western Europe.

Why is Malaysia so conservative?

Malaysia has prospered economically, but still remains conservative and extremely religious. Is this due to Islam or the influence of Saudi Arabia?

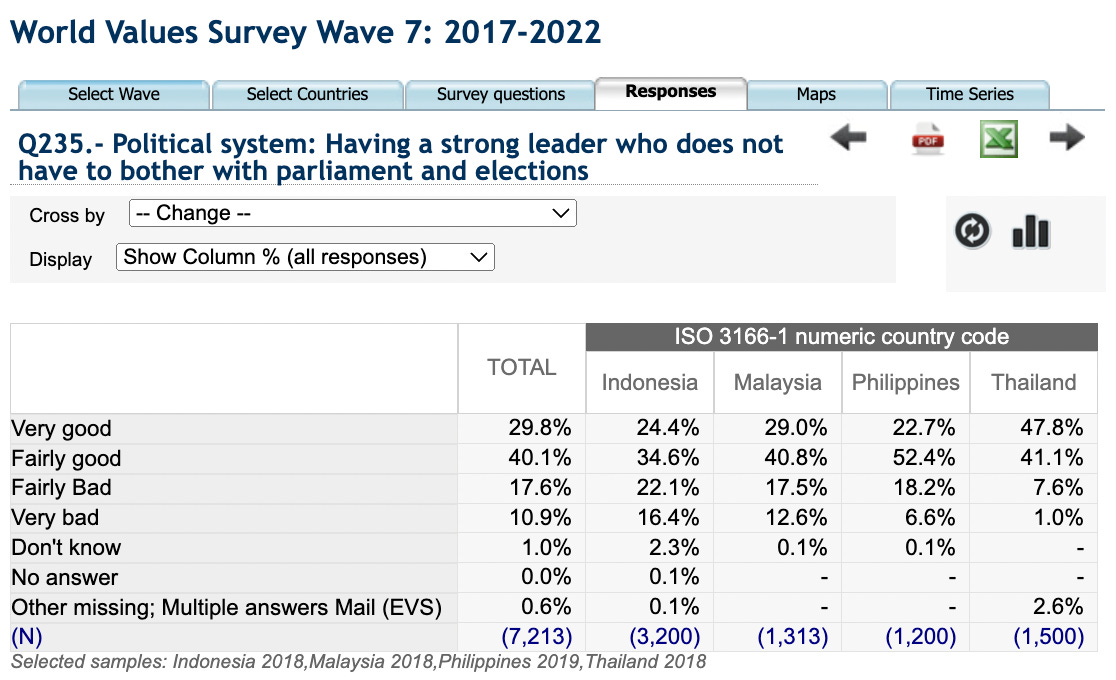

The global Muslim community is certainly conservative and Saudi Arabia has indeed exported its norms, but that cannot explain why the Catholic Philippines scores similarly highly for conservatism.

If you look at World Values Surveys, you’ll see that all rice-growing South East Asians share similar values. Very few want their children to be imaginative. All are extremely religious, they favour strong leaders, tend to distrust new people, and feel closest to their home town. These societies are culturally tight.

They also grow an extremely labour-intensive, interdependent crop: rice.

TLDR

In the West economic development spawned cultural liberalism and individualism. But growth has not had similar effects worldwide. Many prosperous places - like Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and South Korea - remain quite conservative. India’s economic growth has not delivered secularism, but Hindu nationalism.

My explanation is thus:

Cultural change occurs when bold rebels stick their necks out, champion some radical alternative, and successfully encourage wider defiance.

In close-knit, collectivist societies societies, people care intensely about wider social approval, and tend to follow the herd. This suppresses individualism.

Cultural tightness is much higher in societies where:

Agriculture was extremely labour-intensive and required strong inter-dependence (e.g. rice or Andean potatoes), and/or

Intensive kinship meant that commerce, cooperation and marriages were all rooted in a close-knit, endogamous community (tribe, clan or jati);

Authoritarian governance represses dissent and reinforces despondency.

In culturally tight societies (with labour-intensive agriculture or strong kinship intensity), then even as families grow richer, they still care for social approval. This suppresses individual resistance.

My theory can be tested empirically!

I predict that economic growth will foster more cultural liberalisation in societies

historically reliant on crops with low labour intensity

with weak kinship intensity.

Data-wise, I would recommend using the World Values Survey composite score of emancipative values over the past 15 years.

$50 says I’m right ;-)

Much of this sounds like it is simply a matter of timelags. This reminds me of the old debate about 'why is the USA so religious for its level of development? did free market in religion foster selection for uber-religions or something compared to Europe?' It's an old debate now, rather than a current debate, because it turns out US religion has been plummeting for a while and it no longer looks like such an anomaly. It just took time.

Even at the same level of per capita GDP, it takes *time* for any cultural effects to happen and cause convergence, as older generations are replaced slowly no matter how high or low the GDP. For example, South Korea: most of the elderly people in South Korea grew up when South Korean development looked more like subsaharan Africa level than anything like a First World country. Whereas for the USA, that was literally centuries ago. (If you are 80 in SK right now, then you were growing up in 1943-1963 - so literally during the WWII colonization by Japan and then the Korean War. You would have to go back, I think, to, like, the 1700s to find a USA with development equivalent to SK in 1943.) So it is no surprise if SK culture is far more conservative than it 'should' be at its current GDP! That's what happens when you go, within 3 generations, from one of the poorest to richest countries in the world. If you follow SK issues, you can see this massive generational shift at play in their current feminism culture war, where it's gotten very ugly because of the profound rift between 1940s thinking and 2020s thinking. Meanwhile, in Japan, the situation is not ideal but it's substantially more feminist (with a much higher birth rate too); one notes that it's been developed higher for much longer and it had parallel clashes in more like... the Taishō era, over a century ago.

What about Scandinavian countries? They are collectivists as well but have much better gender relations as compared to America which is similarly rich.

Also, why trust in government institutions is so high in Scandinavian countries? While it’s low in other countries of both high and low trust societies.

Is it because of their government system? (Proportional representation instead of first past the post thus leading to more civil political discourse)?