Why does Kinship Vary across the World?

Inherited wealth and the deep roots of patriarchy

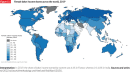

Family descent, inheritance and cohabitation vary worldwide.

Pre-Christian Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia, Central Asia and East Asia were all patrilineal and patrilocal. Clan members lived together, on their ancestral land. Sons were scions of the family line and inherited wealth. Daughters married into other families, then moved away.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, there were two kinds of patriliny. Pastoral communities (like the Tswana) practised patrilineal inheritance of cattle. The Gulf of Guinea was also patrilineal, but in a different way and this is totally overlooked. When a man paid the bride price, he gained ownership of the children. Yoruba patriliny concerns ‘wealth in people’.

South East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa and pre-conquest America were largely bilateral or matrilineal. Descent was traced down both sides of the family, or just the maternal. Under matrilocality, women remain with their kin. In Northern Rhodesia, a young man demonstrated his readiness for marriage by providing his in-laws with several years of ‘bride service’, working on their fields. He was junior.

Caveat: this is a crude synthesis. There are exceptions, like matriliny in Meghalaya and Kerala.

Patrilineal societies tend to idealise virgins, chastity and cloistering

Since patrilineal societies trace descent down the male line, they care about paternal certainty and legitimate biological heirs. Patrilineal societies thus idealise virgins, chastity and cloistering. In Ancient Greece, wealthy families secluded female kin. Women’s names were not uttered in public; they were only recognised as appendages to husbands and fathers.

Caveat: patriliny doesn’t condemn women to become servile baby-machines. Patrilineal Mongol women rode on horseback, managed trade, and represented lineages to Genghis Khan. But that’s an exception. The overwhelming majority of patrilineal societies with inherited wealth idealised seclusion.

Under bilateral or matrilineal kinship, women moved more freely, built independent networks and could gain respect as rulers. Folklore was seldom male-biased and language was not gendered. Today, matrilineal communities are typically more supportive of female leaders. Since male honour is not contingent on female chastity, female employment rises rapidly in response to job-creating economic growth.

Kinship is thus a major predictor of contemporary patriarchy.

Why does it vary worldwide?

Inherited wealth encouraged patrilineal inheritance

This is my theory of global heterogeneity in kinship:

Cattle, the plow and irrigation raised crop yields. Cereals could be traded and stored.

If population growth outpaced available arable land, land became a scarce and valuable asset.

Wealth turned patrilineal inheritance into a key element of social organisation. The more wealth a son inherited, the greater his reproductive success (by attracting wives, concubines and rearing offspring). But in places with high population density, where land was valuable, this was threatened by raiders.

Patrilocal lineages formed to defend valuable herds and land, as well as to provide irrigation, infrastructure, insurance, healthcare, and investment.

Inherited wealth generated concern for paternal certainty. Young women signalled their chastity with nuptial virginity tests, foot-binding, and veiling.

After marrying into patrilocal clans, young brides were outsiders - lacking status and supportive networks. They typically worked on family farms, but were otherwise hobbled so as to preserve male honour.

Land abundance predicts bilateral or matrilineal kinship

Pre-conquest America, South East Asia and the Gulf of Guinea generally had low population density and plenty of available land. Abundant land had no market value. Groups of men could cut down forests to create new fields.

Land was abundant in places with low population density - such as in places plagued by diseases. The Gulf of Guinea’s tropical rainforests incubated parasites and pathogens. Many children died.

High infant mortality combined with land abundance sustained perpetual demand for labour. In pre-conquest America, SouthEast Asia and the Gulf of Guinea, the major source of wealth was in control over people.

As economic historians Peter Boomgaard and Gareth Austin respectively remark of SouthEast Asia and Africa:

‘What was rare and valuable was people and their labor’.

‘Wealth was measured in subjects, and perhaps cattle too, not in hectares’.

Pre-Conquest America, SouthEast Asia and the Gulf of Guinea were thus alike: land generally had low value and coincided with bilateral or matrilineal kinship. Andean ayllu communities practised communal tenure; they traced descent down both male and female lines. Andean non-elite permitted pre-marital sex and encouraged trial marriage, deeming it necessary for companionate marriage. The matrilineal Bemba practised slash and burn agriculture; there was no inherited property.

Caveat: there was sub-regional heterogeneity. Where land was scarce, in highly commercialised regions of Java and Burma, there were pre-colonial land markets. But this was a small fraction. Communities were generally bilateral or matrilineal.

Bilateral and matrilineal societies were NOT feminist utopias!!

In the Gulf of Guinea and SouthEast Asia, women could be respected as spiritual leaders, political rulers, organise independent networks, and traverse independently as long-distance merchants.

However, these regions should NOT be romanticised as feminist utopias. Engels conjectured that private property led to the overthrow of the female sex. He omits what came before: bonded labour.

In the Gulf of Guinea and SouthEast Asia, credit was extremely expensive. The lowest interest rates may have been around 35% a year. Indigenous legal text in SouthEast Asia impose a maximum interest rate of 100%.

When struck by crisis and unable to afford credit, marginal families turned to debt peonage. They became pawns, or sold their female kin into bondage. Wealthy nobles were ready buyers, given labour scarcity. Bonded labour was widespread in both pre-colonial SouthEast Asia and the Gulf of Guinea.

So, while women could gain autonomy and prestige, their welfare was by no means secure. Life was ‘nasty, brutish and short’. Long before colonialism and capitalism, women were captured, sacrificed, enslaved, and died from pestilence.

Kinship is still important, however, as it predicts how families responded to economic and political opportunities in the twentieth century.

Patriliny emerges with cattle, markets and conquest

Thus far I have suggested that scarce valuable land led to patriliny. But kinship was not set in stone. It changed with cattle, markets, conquest and religion.

The spread of cattle killed matriliny

Nomadic pastoralism spread into much of Eastern and Southern Africa through male-biased migration. Pastoralists killed indigenous men and reproduced with the women. Since cattle is a form of inherited wealth, it leads to the consolidation of patriliny.

Disease was paradoxically protective. Pastoralists did not reach the regions with the tropical forests with the cattle-killing tsetse fly.

Wage labour markets enable men to escape matriliny

Young men are inferiors yet not secluded, so there is a strong incentive to escape. In Kerala, when young educated men earnt salaries, they pushed for nuclear families as they wanted to control their own homes. In Northern Rhodesia, men earnt salaries in the Copperbelt and stopped performing bride service. Independent earnings gave them new-found authority.

Markets and other forms of inherited wealth systematically kill matriliny.

Patriliny can be institutionalised after conquest

Ancient Egypt was bilateral, but became patrilineal after the Islamic conquests. To avoid the jizya head tax, Egyptians gradually converted to Islam. Sharia law recognizes succession through the male line, male agnates’ inheritance, paternal ownership of children, and easy divorce for men. This cemented close-knit patriliny.

Paradoxically, patrilineal kinship was also reinforced by the Islamic stipulation of female inheritance rights. Kin marriage kept wealth in the family, while also consolidating fraternal solidarity and shared honor.

Patriliny, once established, is self-sustaining

Since male honour depends on female chastity, women are cloistered. Even if they want to escape abuse and become financially independent, this must be weighed against inevitable shame, stigma and social ostracism.

The converse is never true of men under matriliny. Male escape is not shameful.

The Catholic Church imposed nuclear families

Europe used to be patrilineal. But from 300-1300 CE the Roman Catholic Church and Carolingian Empire stamped out cousin marriage and polygamy. Noble families also leveraged these incest prohibitions to prevent their rivals from consolidating wealth. So before the Black Death, English families were nuclear. Peasants disregarded lineage and rarely exchanged work with extended kin. Precociously deep wage labour markets and urbanisation further accelerated exogamy. Western Europe became nuclear.

Caveat: some manors practised primogeniture (the first born son inherits), so certainly valued female chastity. But this is not the same as patrilocal clans.

Colonialists and missionaries exported the ideal of the nuclear family - sometimes through force, but not always. African missionaries were key to the spread of Christianity. Tswana Chief Sechele, for example, embraced Christianity and promoted it among his people. Polygamy was forbidden, families became nuclear.

TLDR

Kinship practices vary around the world. Patrilocal clans guarded valuable herds and land, bequeathed these to sons, and idealised female seclusion. Where land was abundant, women moved more freely and could gain status as respected authorities.

This is my theory of the global diversity in patriliny, bilateral kinship and matriliny.

Fantastic article, like usual.

I wonder if you don't miss the scale of violence, security dilemmas in ancient societies, kinship networks, familial systems. Also without any stable authority, legal systems could not develop & shape culture over time.

Were we not dependent on nomadic pastoralism, semi mobile opportunistic small bands.

And, the ability to replace males as beasts of burden, applicators of violence has lower cost to the network vs. females who when they live to puberty can produce 10+ children, 50% which will live to puberty.

https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality-in-the-past

Assuming a maternal mortality risk of 2.5% per birth (25% over 10 births) the replacement rate was greater then loss rate.

https://tif.ssrc.org/2020/09/11/carrying-risk-in-antiquity-and-the-present/

While males value was

reproduction

beast of burden

security & violence

this is likely the world for 10,000s-100,000s of years until large scale agriculture, pack animals 5-9k years ago

we are all still quite new to patrilineal systems, just like we are new to large scale industrial development, massive explosion in energy use, high calorie nutrition in the 20th century, communication networks, universal suffrage, legal systems which will all have a profound impact on our culture.

thank you for a wonderful article.

Another explanation is that 'patriarchy' develops alongside other forms of complexity in family systems.

The hunter-gatherers' nuclear family (with a relatively high status for women and loose family ties) is gradually complexified by successive innovations in family systems. Like others (agriculture, state, writing...), these innovations appear in a few key points before spreading. For Eurasia, these points were the Fertile Crescent and China. Distant regions, such as Western Europe, retained primitive characteristics, including the relatively high status for women of the nuclear family. The same is true in southern Africa, far from the Niger and Egypt. And so on in Americas and Oceania.

The data strongly support this theory: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0279864

Besides, the Catholic Church merely formalizes a pre-existing family system: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279864.s001