“There’s no way he can do it” - Inuits insisted.

Without his wife, a man simply could not survive. Her work was crucial. In the global history of gender, this was rather unusual. Elsewhere, men were glorified as providers, protectors and scions of the family line.

Why were the Inuits so gender equal, and what does this teach us about gender equality?

This Substack outlines:

Ethnographic evidence about Inuit divisions of labour, spirituality, sexuality, infanticide, and collectivism;

How this challenges the plough theory of patriarchy;

Why were the Inuits so gender equal? and

Implications for contemporary progress towards gender equality.

What’s the evidence?

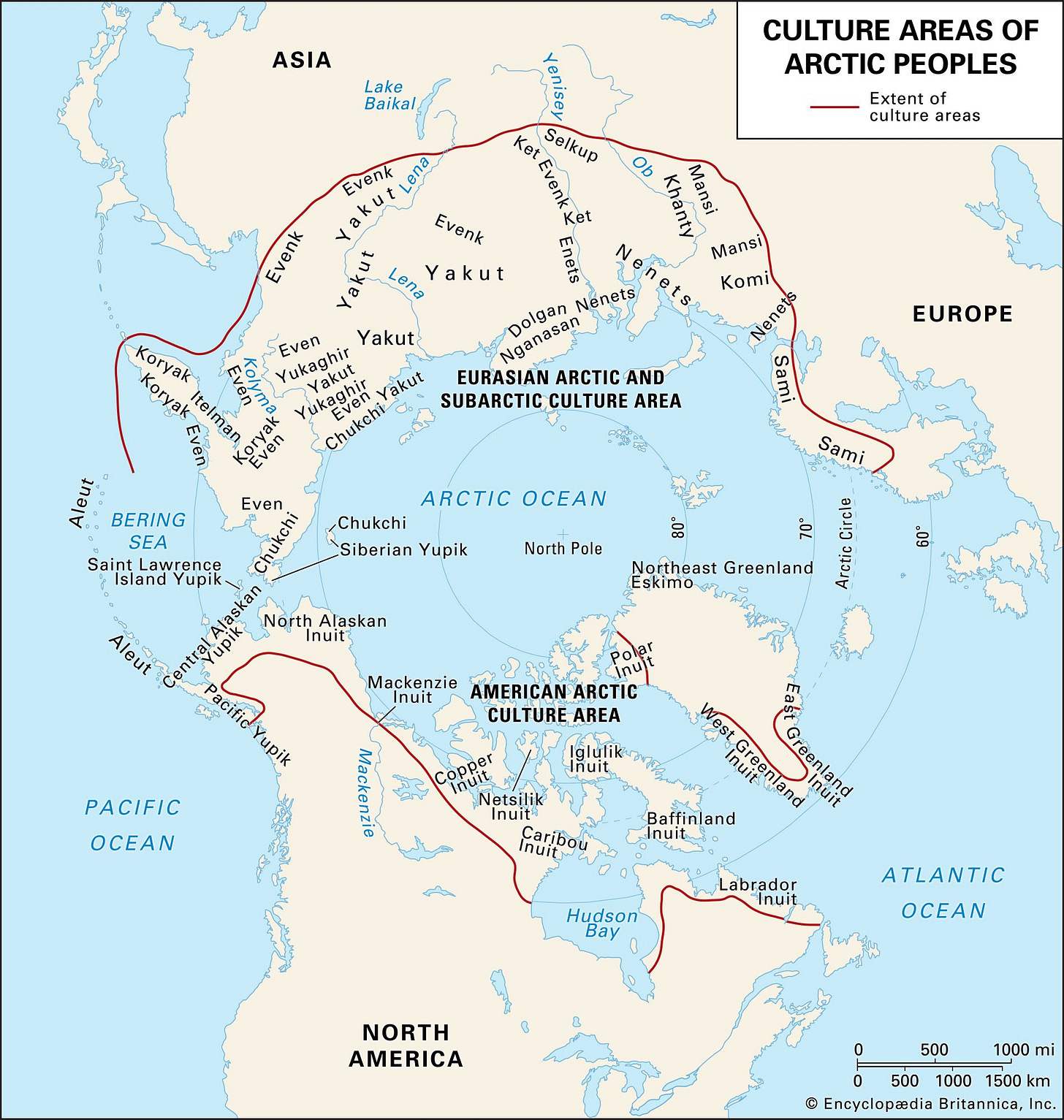

Small, nomadic communities embraced harmony with nature and left little trace. There was no call for writing nor ostentatious monuments. The earliest data comprises oral histories and observations from the late 19th and early 20th century. By this time, Inuit communities had undergone substantial change, emanating from: intensified trade in fur and whaling; pathogens and population decline; as well as conversions to Christianity.

Even before European contact, there were centuries of flux. Inuits adjusted to climate-induced shifts in resources through seasonal migration, and innovating with diverse types of social organisations. Observations and recollections from the past hundred years should not interpreted as evidence of how things always were.

Let us thus proceed cautiously.

Inuit husbands and wives were seen as interdependent

Instead of celebrating children’s birthdays, Inuits commemorated achievements - like the first time they killed a rabbit.

Bachelors improved their marital prospects by signalling skills and generosity. Back in the 1960s, a young man demonstrated his usefulness to her family by sharing food from his hunt; building a snow-house; repairing her father’s kayak; and collaborating as his hunting partner. Young women likewise aided his female relatives. (This sharply contrasts with patrilineal China, Egypt, Iran and India, where ‘good girls’ signalled virginity).

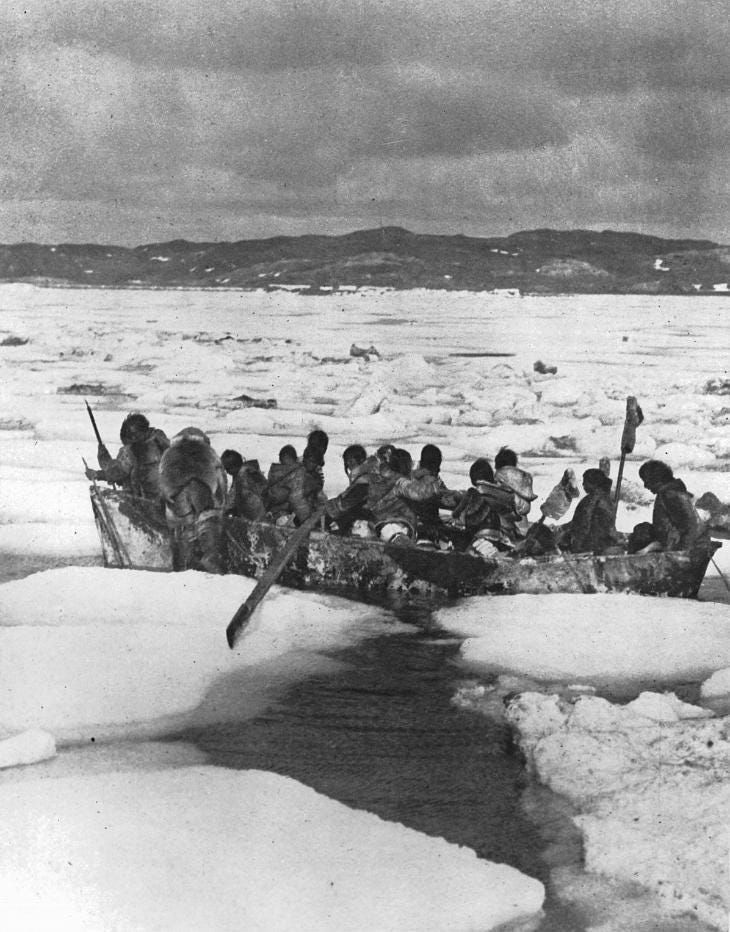

Spousal cooperation was manifest through labour. The sexes were defined as providing vital work for each other, as husbands and wives. Men hunted fish, walrus, seal, whale, and polar bears; then women transformed these hides into warm, waterproof clothing, made kamiks (boots), dressed the umiaq (whaling boat), sewed summer tents, and redistributed meat. Women’s skills saved lives, protecting hunters on dangerous journeys through the Arctic.

“This is what we have always known. When a mother loses a husband, she can sew, or she can get food by begging or working for it. But when a husband loses a wife, he can't do anything”.

“I always remember what Kagak said. When he lost his wife, he came over to see me. He told me I was able to do a lot because I was able to mend his kids' clothing. But when a husband loses a wife, even if he has a lot, here is no way he can do it”.

Spiritually, motherhood was revered

The Inuit creation myth has no men, just a woman who bore a litter of dogs.

Sedna was the goddess of the sea and mother of life. She only released sea mammals for the hunt when satisfied by humans’ good behaviour. A female goddess was the ultimate arbiter. Reflecting an ideology of gender complementarity, Sedna had male associates (the dog), just as the spirit of the moon has female associates (like Aukjuk).

Sexuality was not repressed

Adolescents were free to explore their sexuality, without censure or condemnation.

Adoption was also practised by the Inuits - since they had little concern for paternity or legitimate heirs. Wife swapping was also common, at least until the 1940s. This was generally consensual and temporary, undertaken at rituals, probably to strengthen community bonds.

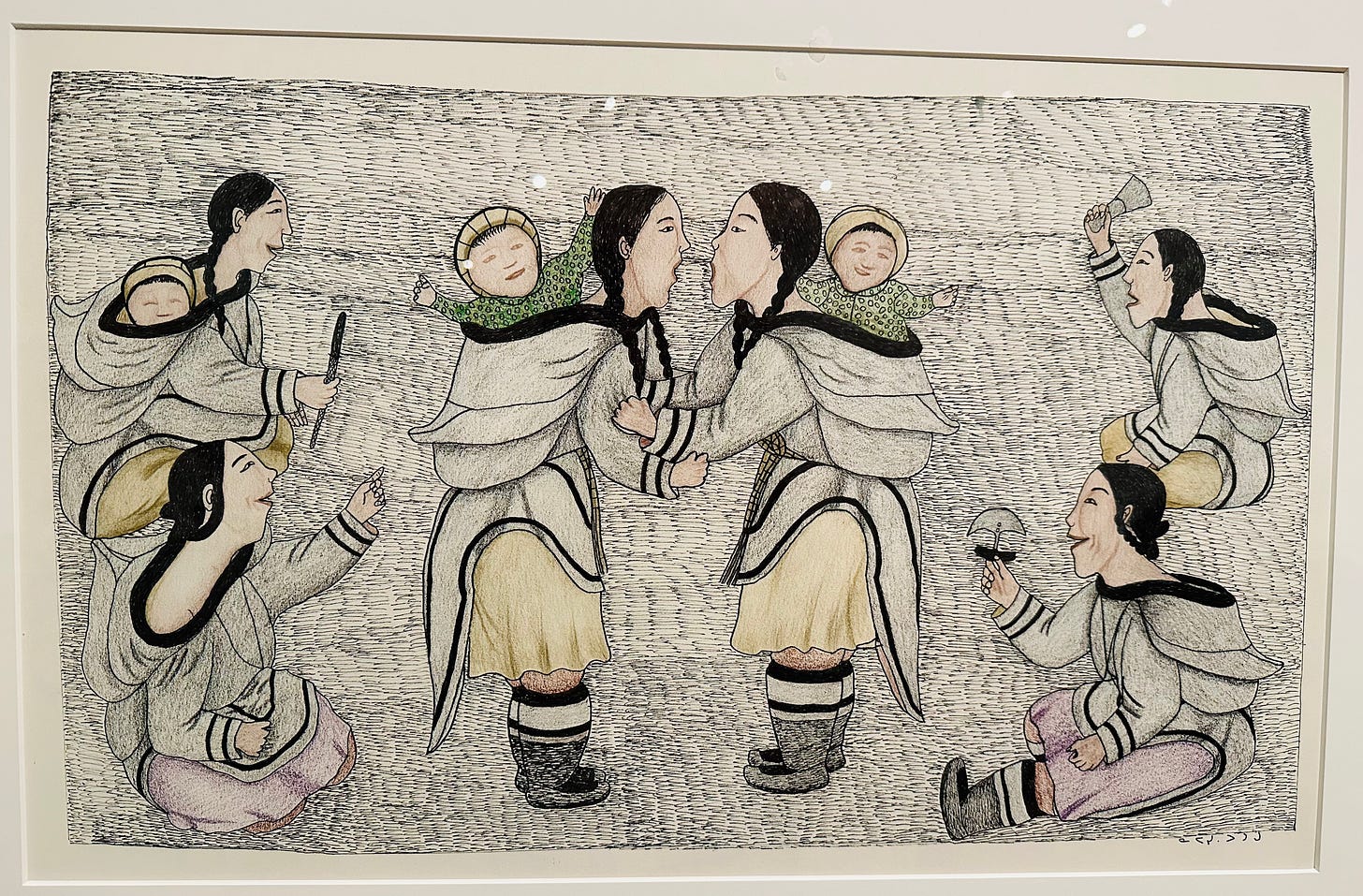

Everyone socialised together, in the evenings. Men and women told stories, made music, danced, and performed shamanic rituals.

Female creativity is given equal place. Kattajaq is Inuit throat singing; two women alternate breath exhalations to create a rhythmic call and response. This friendly competition tests vocal endurance and builds sorority.

The Inuit Tivajuut Festival honours fertility. Both men and women wore masks to participate in this spiritual ritual.

One Inuit mask dance is called uaajeerneq. With their face painted to represent male and female genitals, the performer erratically jumps on the audience, in a way that is both scary and sexy. Female sexuality was quite clearly not repressed.

Collectivism

Inuit morality emphasises working towards the common good and generously sharing that bounty. Collective interests are paramount, as determined by elders. This was no liberal free-for-all. Inuits instilled gender divisions, arranged marriages and killed baby girls.

Gendered divisions of labour were reinforced through ridicule. Women typically remained with children, close to the camp. They caught geese, ducks, foxes and shoreline fish. On Belcher Island, menstruating women were forbidden touch men’s hunting tools.

Elders were owed respect, regardless of gender. Governance styles varied, however. In some regions, ethnographies suggest that female and male elders discussed all important issues; elsewhere men exercised greater public authority.

Arranged marriages were historically normal - according to interviewed older women. Infants were betrothed, then taught to obey their elders. In this respect, neither gender exercised sexual freedom. Girls were often scared, angry and upset, but powerless to resist:

“There stood a man with long hair, mustache, bearded. I was really scared! He was there to go to bed with me!.. I thought he was creepy. I was 16; a year later, my first baby was born”.

“A man who was old enough to be my father came to our camp to speak to my parents. … My parents told him that he could have me as his wife, and I was sick with anger and sadness but could say or do nothing. There were many times when he would go out.. and I wished that he would never come back alive”.

“In my day, even though the women didn’t agree to marry, once their parents had made an agreement with the other parents, the marriage was arranged without the women having any say and there was no way out of the arrangement. We didn’t dare try to separate or get divorced because we had no rights at all except to listen to and respect our parents”.

(Though other accounts suggest unsatisfactory relationships could be terminated).

Sex ratios were highly skewed. Baby girls were put out on the ice and left to freeze. Why did Inuits do this? The most likely explanation is that sex-selective infanticide ensured even ratios in adulthood. In the perilous North, many men died while hunting. Male deaths in adulthood are directly correlated with female infanticide. Even sex ratios in adulthood were conducive to gender equality: they suppressed polygamy and enhanced women’s bargaining power.

Inuits were not tolerant liberals; they did not respect individual rights. Order was maintained through ridicule, menstruation taboos, arranged marriages and infanticide and obedience to elders. None of this should be romanticised away. Instead we might ask,

How come women had status despite coercion? How does it all fit?

Do the Inuits fit with popular theories of patriarchy?

Esther Boserup famously theorised that plough-cultivation encouraged patriarchy because it rewards upper body strength. Men worked outside the home, while women processed cereals indoors. Female domesticity became naturalised.

Alesina and colleagues find that traditional use of the plough is correlated with lower female labour force participation and more patriarchal norms today. This paper has gained serious traction, with over two thousand citations.

But have they accurately identified the causal mechanisms?

Boserup’s theory is untrue, on two counts. Domesticity entails neither seclusion nor subordination. While an igloo certainly represented the female domain, domesticity was never denigrated. Even if Inuit women historically spent time indoors, they have since been quick to seize job opportunities and provide for their families.

Boserup and Alesina confuse cults of female domesticity and seclusion. Although these two appear superficially similar, the underlying rationales are totally different, and thus respond very differently to economic opportunities.

In the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia, men’s honour is contingent on female chastity. It’s all about control of sexuality. Female employment remains low - unless available earnings are sufficiently high to compensate for men’s loss of honour.

The Inuit also demonstrate the importance of culture. Worldwide, women and men have always been interdependent, the actual activity is immaterial. What matters is whether this is work is valued.

Why were the Inuits relatively gender equal?

Loyal followers already know my theory, and Inuit culture fits this perfectly!

Elsewhere in the world, patrilocal clans coalesced to protect valuable assets, bequeathed wealth to male heirs, and idealised female chastity. Men then dominated institutions and preached their own primacy. A powerful myth prevailed,

Men do not depend on women.

Since Inuits lacked heritable wealth, they did not develop patrilocal clans. Kinship was bilateral: newlyweds maintained relationships with paternal and maternal relatives. A wife did not take her husband’s last name, for there were none. Adoption was common; men cared for the children of other men (quite unlike patrilineal societies).

Given scant concern for paternity, women were never secluded nor was their sexuality restricted. Women could thus fraternise freely, collectively contest male authority, and champion their own contributions. By speaking out during community meetings, female elders shaped narratives about the ‘common good’.

Random question: do you plan to write about societies that had matrilineal inheritance? I would be really interested to see your discussion of that.

Wow wonder article! Really interesting