The Economics of Resentment

A new paper by Sahil Chinoy, Nathan Nunn, Sandra Sequeira and Stefanie Stantcheva examines beliefs that the world is ‘zero sum’: your success is my loss. If prizes are not only scarce but fixed, then one person’s victory comes at another’s expense.

This paper is fantastic and it has hugely important global implications - for racism, religious violence, xenophobia and authoritarianism.

US Results

Chinoy and colleagues surveyed 14,500 participants, over five waves, between 2020 and 2022. They inquired about ancestry, government policies, and zero sum mindsets:

Ethnic: “If one ethnic group becomes richer, this comes at the expense of other groups.”

Trade: “If one country makes more money, then another country makes less money.”

Citizenship: “If non-U.S. citizens do better economically, this comes at the expense of U.S. citizens.”

Income: “If one income group becomes wealthier, this comes at the expense of other groups.”

Zero-sum thinking is associated with support for redistribution, awareness of racial and gender discrimination, as well as being anti-immigrant.

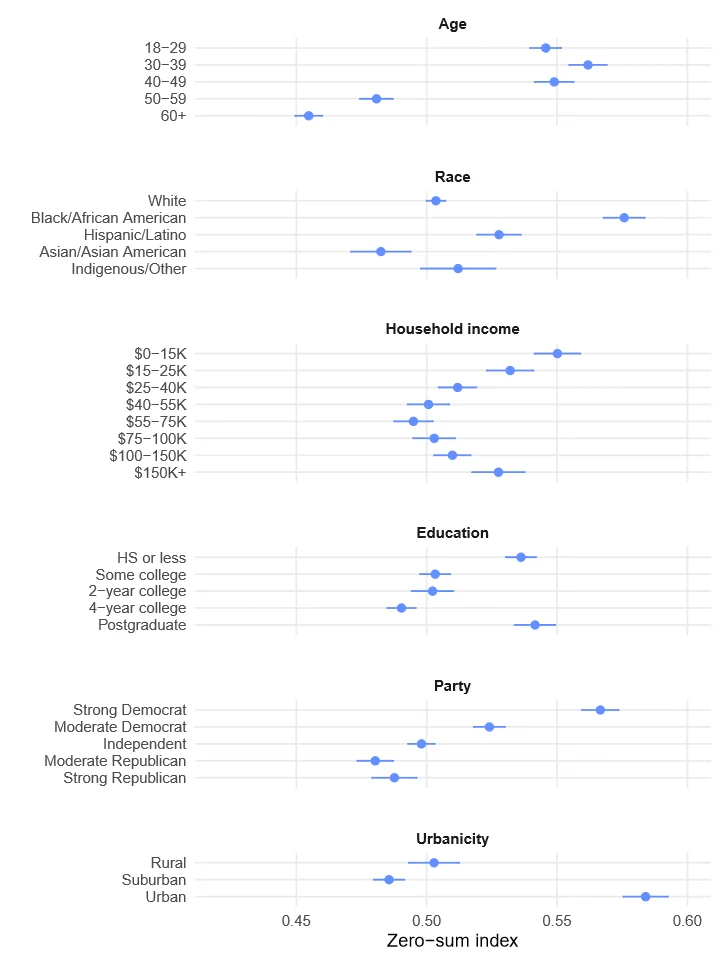

Younger groups and Black Americans are especially zero-sum. They’re more likely to say that when one group thrives, another is disadvantaged.

Why might this be?

Economic immobility

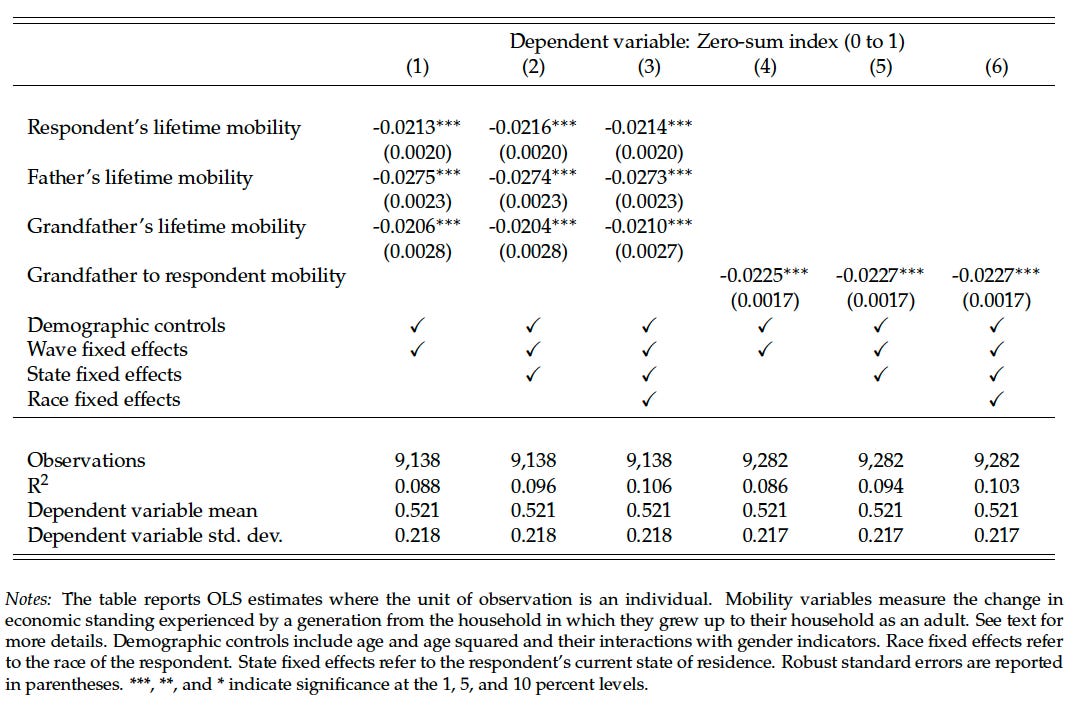

Zero-beliefs are strongly associated with economic immobility. If individuals and their families have not experienced intergenerational upwards mobility, they tend to say that opportunities are scarce and fixed.

Immigrants - who have experienced huge upwards mobility - are more likely to be positive-sum. They’ve seen massive improvements in economic well-being and believe this is possible more generally.

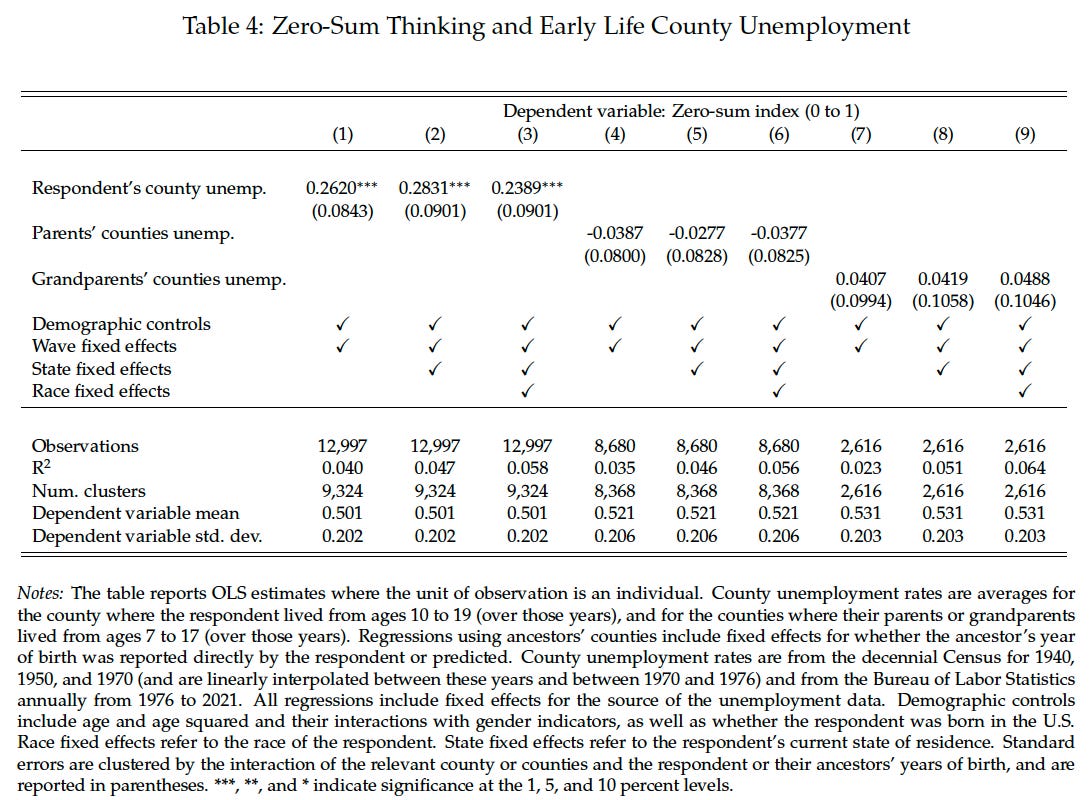

Local economic geography also matters. If you grew up in a place with high unemployment or fewer immigrants, you’re more likely to believe that opportunities are restricted. More for them is less for me.

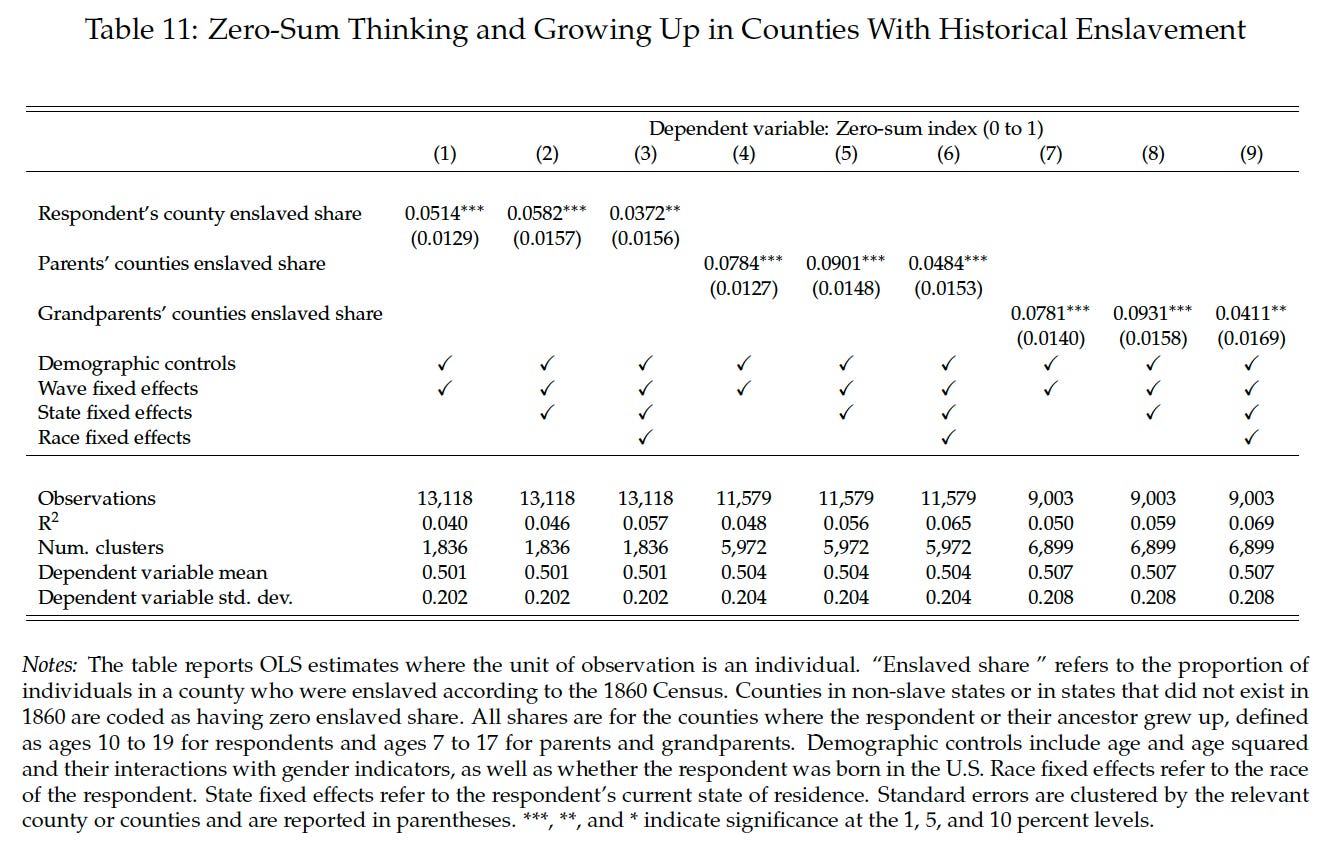

White Americans from counties with historical enslavement are also more likely to be zero-sum: their rise means less for us.

International Results

The World Values Survey asks 200,000 respondents from 72 countries to score the extent to which they believe the world is zero sum:

“People can only get rich at the expense of others” versus

“Wealth can grow so there’s enough for everyone”.

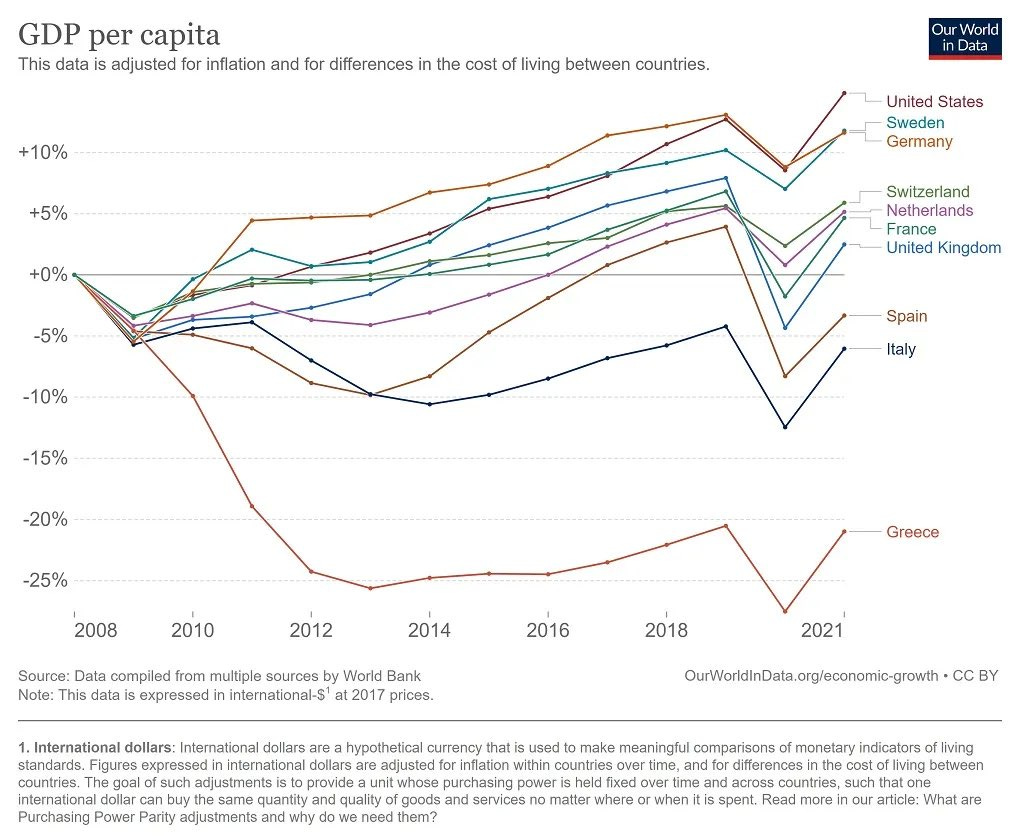

Over at the FT, John Burn Murdoch uses this data to tell a hugely important story. Globally, people who experienced high economic growth in their youth are much more likely to believe that everyone can thrive. Decceleration of economic growth has bred zero-sum mentalities.

The message is clear:

Families who’ve personally seen and experienced upwards mobility are more likely to believe that everyone can thrive.

Are you convinced? Personally, I think it’s brilliant!

Wider parallels

If socio-economic prizes are scarce, people may feel intense resentment of outsiders who are not seen as contributing to their own or their group’s success.

Consider the following applications:

Why are religious tensions rising alongside economic inequality and joblessness in South Asia? Why are temples being destroyed and men being accused of ‘love jihad’?

Why might Zambian slum-dwellers’ success incite their neighbours’ bitterness?

Why is South-Eastern Europe so conservative: what explains persistent aversion to feminism and immigration?

What explains the rise of the right in Italy and Greece?

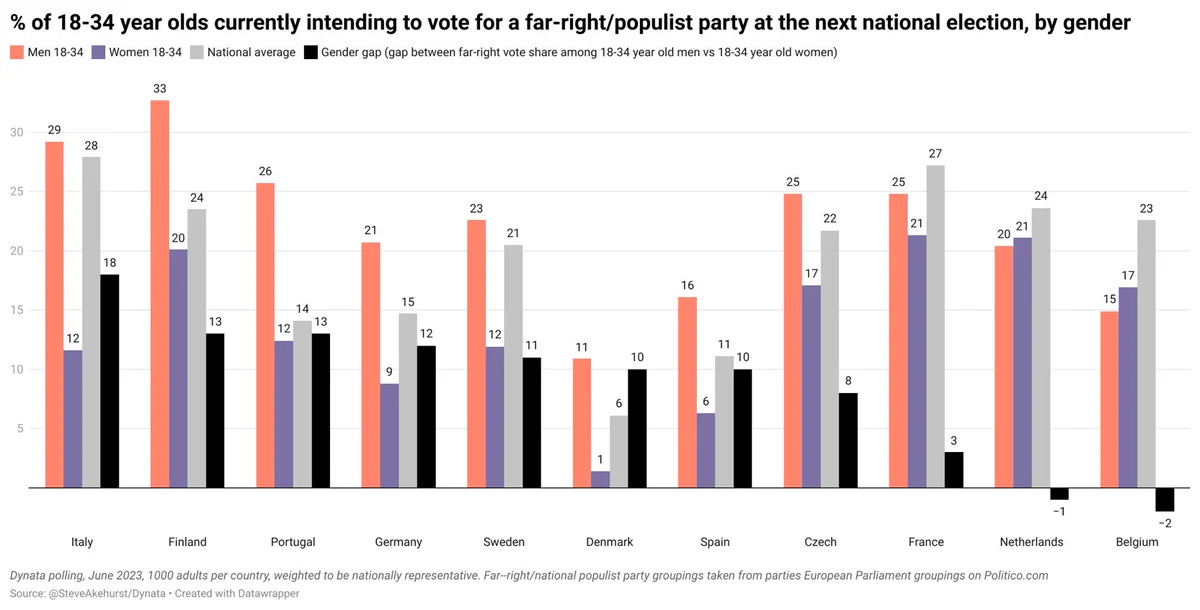

Why do a quarter of European young men say they’ll vote for the far right?

Why does unemployment often trigger hostile sexism - in Egypt and the US?

Why were women’s magazines so catty, highlighting celebrities’ physical flaws?

Why might a senior professor resent a young academic and try to tear her down?

Why did anti-Semitism increase after the Protestant Reformation, in areas where Jews competed with the Protestant majority, especially in moneylending?

Under a ‘zero-sum’ mentality, resentful hostility makes sense. Economic stagnation, rampant discrimination, and intense competition foster jealousy.

Of course, bias can be compounded by organisations, ideological persuasion and institutions. If Hungarians and Hindu Indians struggle to get ahead, they may be more susceptible to nationalist propaganda, and then vote for authoritarian strong men who punish critics, clamp down on civil society, and entrench their hegemony.

Social media filter bubbles may also shape the direction of ‘zero sum’ mentalities. This could be left or right. Charismatic politicians may try to evade blame for economic stagnation by scapegoating immigrants.

Personally, I’ve never experienced emotions like envy, so I’ve always observed these dynamics like a mystified alien. Thanks to Sahil Chinoy, Nathan Nunn, Sandra Sequeira and Stefanie Stantcheva for elucidating the economics of resentment!

This creates a feedback loop, doesn’t it?

Economic issues leads to authoritarianism which leads to extractive institutions which again lead to economic issues. How can a country prevent that?

Economics is not zero sum, but social status issues tend very much to be zero sum. Unfortunately, once people are above the survival threshold, they tend to care more about relative status.