The Economic & Cultural Drivers of Violence

What do the Rohingya genocide, witch-hunts, and agro-pastoral conflicts all have in common?

These are all violent land seizures, triggered by economic shocks, justified through vilification, controlled by exclusionary institutions. Let me explain, by discussing three excellent Economics papers.

The Rohingya Genocide

A new paper on the Rohingya genocide has rocked my priors. I thought this persecution was motivated by religion. Actually, it may have been more materialist.

Davis, Lopez-Pena, Mobarak and Wen (2023) leverage price fluctuations for rice (the local staple crop). They find that state violence against ethnic minorities increased when expropriation was most profitable. State-perpetrated looting increased in rice-growing areas precisely when rice prices rose.

Ideological persuasion legitimise attacks on the Muslim minority. Myanmar’s military propagated hate in order to incite rape, murder and religious persecution. A UN fact-finding mission found that this was facilitated by Facebook.

Land grabs may have been motivated by economics; propaganda made it seem righteous.

Witch hunts

Hundreds of witches are killed every year in Tanzania. Elderly women are demonised and killed by their own relatives. Witch murders double - finds Edward Miguel - in years with extreme rainfall (droughts and floods).

Witch-hunts may have also facilitated the transition from matriliny to patriliny. Govind Kelkar and Dev Nathan find that witch-killings often involve seizures of land. Just like Myanmar, vilification legitimised property grabbing.

Culture matters, of course. Most Tanzanians believe in witchcraft. Communities only tolerate these killings because they fear witchcraft as dangerous. “In the Sukuma community, if you kill a witch it is not really considered a crime. It’s like you are doing something for the community”.

A new cross-national analysis by Gersham suggests that witchcraft beliefs are more prevalent in places with weak rule of law, cultural tightness and zero-sum mindsets (one person’s gain is always someone else’s loss).

Farmer-herder conflicts

Nigeria’s religious conflicts go back at least two hundred years (see excellent books by Ousmane Kane, Olefumi Vaughan, and Moses Ochonu). Climate breakdown may be making it worse.

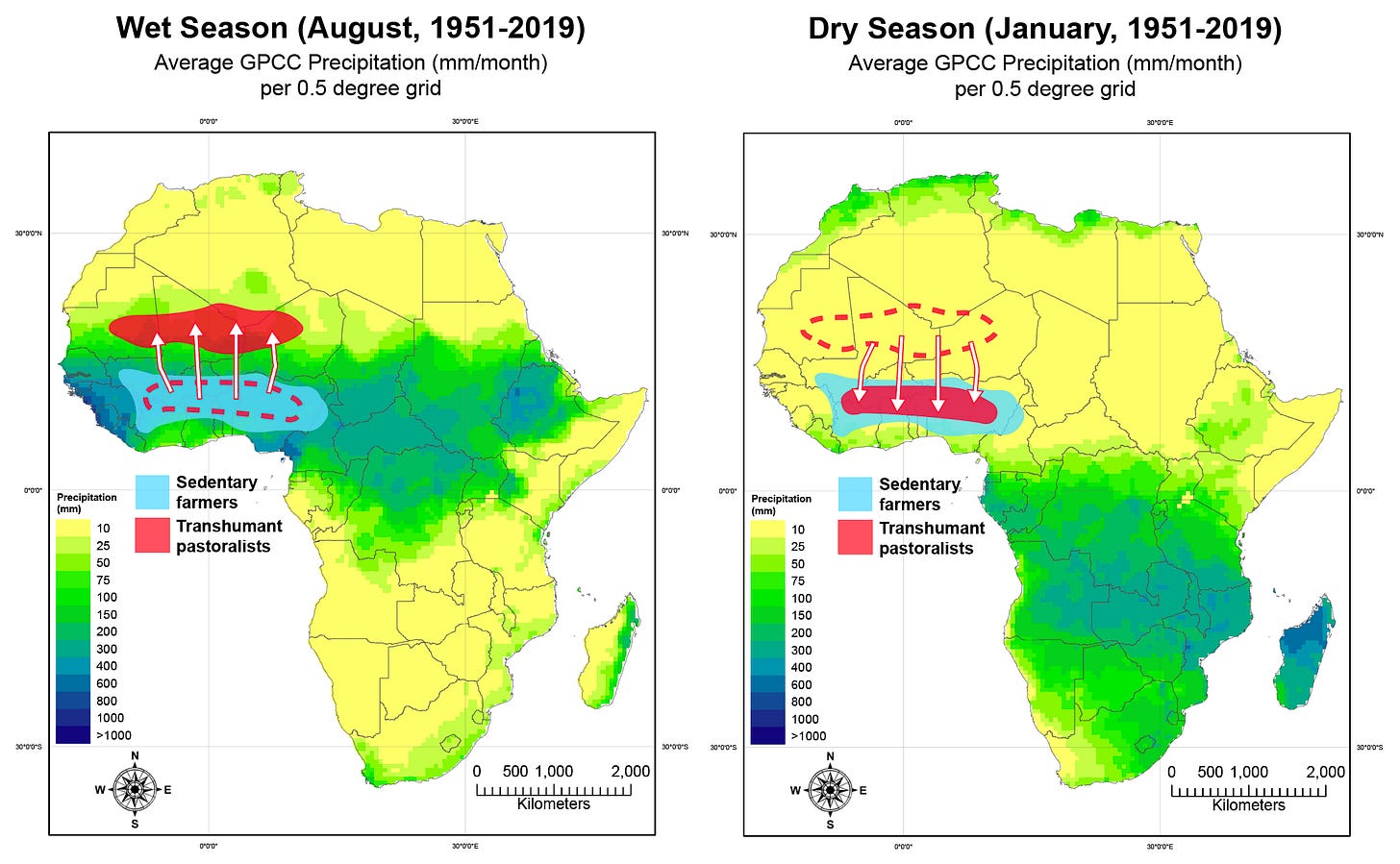

Desertification is pushing nomadic herders further south, in the search for fertile pasture - explain Eoin McGuirk and Nathan Nunn. Where their cattle graze, crops are destroyed. Farmers fight back and violence escalates. Thousands are being killed. Since pastoralists are mostly Muslim and farmers are Christian, economic struggles then take on the mantle of religion.

Institutions also matter.

Only in polities where pastoralists are politically excluded do droughts massively exacerbate agro-pastoral conflicts. The economically-motivated and ideologically-justified persecutions of the Rohingya were likewise facilitated by exclusionary institutions. Since 1982, they have been denied citizenship rights. Over in Tanzania, all-male sungu-sungu councils authorise witch-hunts - as a central part of their role in ensuring village security.

Corporate algorithms can also be conceptualised as a kind of institution. By favouring inflammatory content, nurturing filter bubbles and creating falsehoods, these too function as online ‘rules of the game’.

So what do the Rohingya genocide, witch-hunts and agro-pastoral conflicts have in common? All these fights for land are triggered by economic shocks. But communities only tolerate violence against a very specific group - which is a function of cultural persuasion and exclusionary institutions.

I have an as-yet unproven hypothesis at *all* wars are actually about resource conflicts, even the ones we think are about religion, even the Crusades. Religion is a huge part of people's identity and becomes a way to motivate and rally people, but resource conflict drives it all. Without resource conflict, people of different religions or ethnicities tolerate each other just fine.