Sub-Saharan Africa's Economic Stagnation

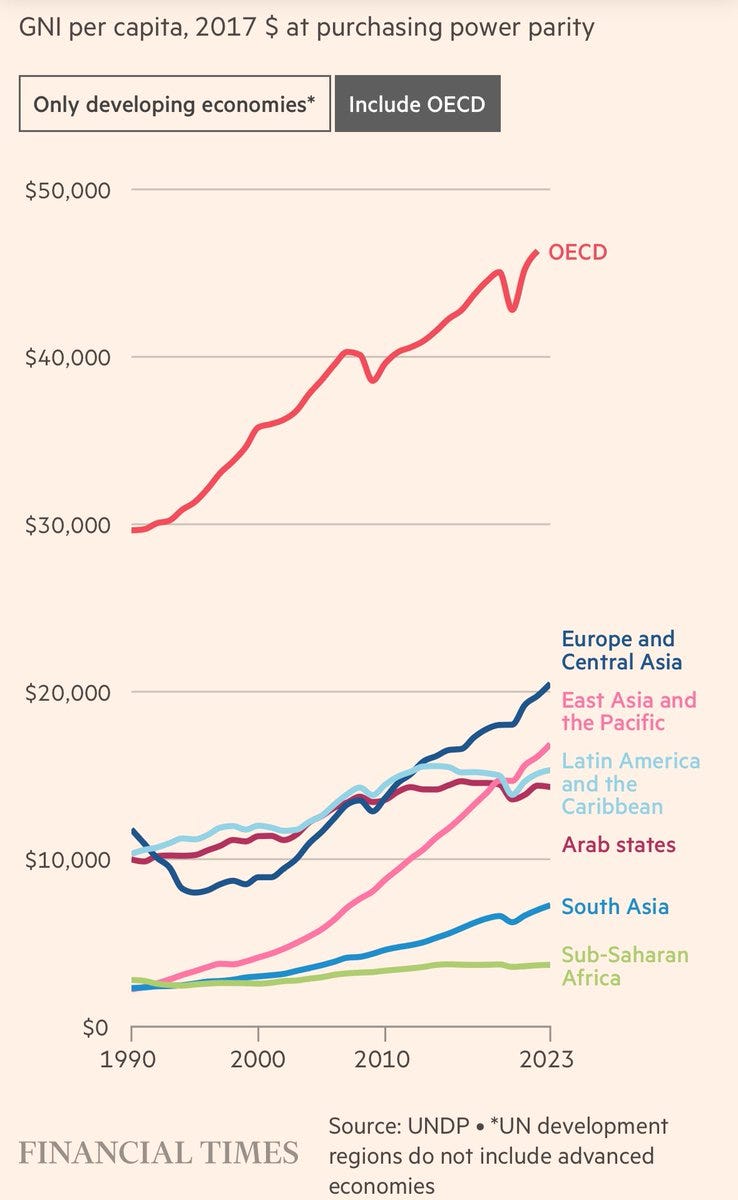

Over the past 30 years, Sub-Saharan Africa has seen zero change in GNI per capita. What does this mean for gender?

While Sub-Saharan Africa has great diversity (especially by religion, economic class, and livelihood systems), one trend is clear:

In low-wage economies, girls tend to marry young, bear many children, then remain trapped in back-breaking agriculture, or trapped in saturated informal markets. Many are also at high risk of violence, which remains normalised, largely due to poverty and conflict.

Over the past 30 years, Sub-Saharan Africa has seen barely any change in GNI per capita. More than half work on farms - which are typically small and unproductive. Africa’s crop yields have stagnated, unlike the rest of the world. Only 3.5% of agricultural land is irrigated.

Climate breakdown poses a further threat, destroying crops and pasture for livestock, thus hurting exports and pushing up urban living costs. In Sub-Saharan Africa, hotter weather is associated with lower GDP per capita.

Innovative entrepreneurs face major hurdles

African firms tend to grow very slowly, and are much smaller than other countries, even controlling for market size. Access to finance is a major constraint - worsened by low rate of savings, uncompetitive banks, and falling FDI. Credit is thus extremely expensive.

78% of firms in Africa experienced annual power cuts in 2018. Each year, African firms lose 25 days of economic activity through power cuts. Transporting goods in Ethiopia and Nigeria costs 3.5 and 5.3 times that of America.

The economic gulf between Sub-Saharan Africa and the rest of the world is growing.

Back-Breaking Drudgery

Sub-Saharan African women work at very high rates. So if one looked at this one indicator, one might infer that the region is extremely gender equal.

However, labour force participation includes unpaid drudgery on family farms. In Uganda, Tanzania, Ghana and South Africa, women are spending most of their days on home production.

Back-breaking drudgery in agriculture does not enhance women’s status, social networks, or independent autonomy. Indeed, it is not necessarily recognised as ‘work’.

Subsisting on very low incomes, unable to afford domestic appliances (like kettles, ovens or washing machines), sometimes without electricity or piped water,African women generally spend an enormous amount of time working in their homes.

Even when Sub-Saharan African women do work for markets, this is rarely in salaried employment. They are much more likely to have a little market stall or work for a family business - without pay.

Why are North and Sub-Saharan Africa so dissimilar?

It’s important to recognise that they face different binding constraints. Across North Africa, men’s honour depends on female seclusion, so women mostly remain at home. Sub-Saharan African women are generally much more responsive to economic opportunities.

With economic growth, women in Mauritius, South Africa and Ghana have seized new jobs in services. Malawian women are equally mobile, they are not physically restricted. Many communities are matrilineal. But the country remains very poor and agricultural, so women are trapped in back-breaking hoe-cultivation.

State Capacity remains Weak

Economic stagnation inhibits government effectiveness. Thus even though Sub-Saharan African parliaments include many female legislators, and have passed many gender equal laws, implementation is weak - as shown by Peace Medie.

Almost a third of adolescent girls have experienced physical or sexual violence

“One in four adolescent girls report having] experienced violence, and one in seven report having experienced sexual violence in the previous year”.

That’s the top-line finding from David K. Evans, Susannah Hares, Peter Holland, and Amina Mendez Acosta, after analysing Demographic and Health Surveys of the 20 most populous African countries (over 80% of the regional population).

In Montserrado (Liberia), 35% of women reported early sexual engagement [legally regarded as statutory rape], 40% of male assailants worked at schools.

Schools are not safe spaces, but neither are homes. Evans and colleagues find that Sub-Saharan African girls are just as likely to have experienced violence regardless of whether they attended school.

Girls are especially likely to have been sexually abused if their fathers have died, such as from HIV/AIDS.

Violence is pervasive - largely due to poverty and conflict

Intimate partner violence is also very high in Sub-Saharan Africa. This is strongly associated with low education and poverty. This holds worldwide and within Africa.

34% of adolescents in Cape Town have experienced physical violence, which in turn hurts their cognitive development.

Poverty begets intimate partner violence in several ways. Economic desperation exacerbates stress and marital disputes. Impoverished girls wed early - with scant resources, support systems or much understanding of the world. And child brides are more likely to be abused.

One time, a doctor and I were driving through rural Zambia. By the roadside, we saw a young girl. Her face was horribly swollen, her body was covered in cuts, and stubbled hay. Maybe she had been dragged through the field. Barely 16 and recently married, she wanted to run away. But where to?*

High fertility increases mothers’ economic insecurity

Women who have five children, and lack independent salaries, may feel extremely dependent on their husbands. Where can they go? Who else will look after them?

I spent six months living in a shanty compound with a locally elected councillor in Kitwe (Zambia). This area was very poor: there were no street lights, nor tarmac roads, nor indoor water. We cooked by making fires and washed with a bucket behind a bush. Barely anyone had a salaried job. Victims of male violence sometimes came - bloodied and bruised - asking the councillor for help. One had an engorged eye, her entire face was red, swollen and terribly disfigured. She asked for advice. But what were her exit options?

A couple of months ago, I received a message on Instagram. A Zambian woman (who had hosted me in a remote village) had been abandoned by her husband. He had re-married, and taken all their assets. Destitute, she was now living in a shack. She couldn’t simply make money because she didn’t have the capital to buy dried fish for re-sale. Obviously I wanted to send money, but even that was difficult since there was no local infrastructure for digital payments. Instead, another relative had to travel six hours to Lusaka to physically pick up the cash.

Many Sub-Saharan Africa women face similar challenges: they bear multiple children, struggle to secure decent work, and then remain economically insecure. While abused women could leave, many stay because they believe their children will be better off. In Zambia, I heard one term repeated over and over again:

“Ukushipikisha” (to endure)

Cultures of violence reinforce acceptance. Almost 70% of Sub-Saharan Africans say that parents may be justified in beating their children. This share is lower among those who are educated and wealthier. But since Sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP per capita remains low, violent discipline remains widely accepted.

Central Africa has exceptionally high rates of intimate partner violence - just like other conflict-afflicted places (Iraq and Afghanistan). Cultures of violence spread across multiple domains - both criminality and people’s homes.

TLDR

Gender interventions will have the highest returns if they address regionally- and country-specific binding constraints. Across Sub-Saharan Africa, this is primarily economic stagnation and violent conflict.

Of course there is a lot of ethnic and religious variation (just look at North and South Nigeria), I merely highlight how SSA’s gender relations are affected by economic stagnation.

Further Reading

Global Norms and Local Action: The Campaigns to End Violence against Women in Africa by Peace A. Medie

“Time Use and Gender in Africa in Times of Structural Transformation” by Taryn Dinkelman and L. Rachel Ngai

“Adolescent Girls’ Safety In and Out of School” by David K. Evans, Susannah Hares, Peter Holland, and Amina Mendez Acosta

“Cities as Catalysts of Gendered Social Change? Reflections from Zambia” by

Alice Evans

‘Women Can Do What Men Can Do’: The Causes and Consequences of Growing Flexibility in Gender Divisions of Labour in Kitwe, Zambia by Alice Evans

“Women’s decision-making capacity and intimate partner violence among women in sub-Saharan Africa” by Bright Opoku Ahinkorah, Kwamena Sekyi Dickson, and Abdul-Aziz Seidu

Thanks for writing this!

Very sad that GDP and yield have stagnated in Africa. There is definitely limited state capacity which I think is from limited voice of the populace which in turn is due to a culture of corporal punishment and prioritizing subservience rather than actual learning in Education. The graph you showed of decreased acceptance of corporal punishment is encouraging. We might be seeing the result of this with the recent youth protests in Kenya where a generation who were not as brutally punished for having different ideas have found their voice. Let's hope!

Note: the impact of climate change (figure 12) is *projected* not actual.

I have been looking for data to show what the climate impact on Africa is and have yet to find it. As far as I can tell global warming would have sligh positive benefit for Africa.

https://www.africanaccelerationism.com/p/global-warming-the-lesser-of-two Though I'm happy to be corrected on that.