“Reader, I Married Him”

Patriarchy isn’t just determined by geography, states, or economic activity. Culture really depends on what communities celebrate and value - their pathways to status and social inclusion. Equality flows from transforming how we see and relate to each other. Charismatic storytelling is thus a powerful force for change!

Back in the 19th century, when women lacked the right to vote or even own property, English women novelists pioneered a revolution, masking radicalism with romance. They celebrated marriages based on mutual understanding and male devotion. Reaching educated homes across the country, women novelists helped make equal partnerships deeply appealing.

The Protestant Reformation

English novelists built on religiously sanctified ideas. Protestant churches already emphasised the spiritual importance of marital love and intimacy. By the 17th century, religious leaders actively criticised husbands who showed insufficient marital devotion. The English Puritan Robert Cleaver insisted that a husband should not treat his wife like a servant, but act in ways that would “rejoice and content her”.

Neil Cummins’s research on English wills reveals this shift in action – over the 17th century, men increasingly used affectionate language when referring to their wives.

The Rise of Women Writers

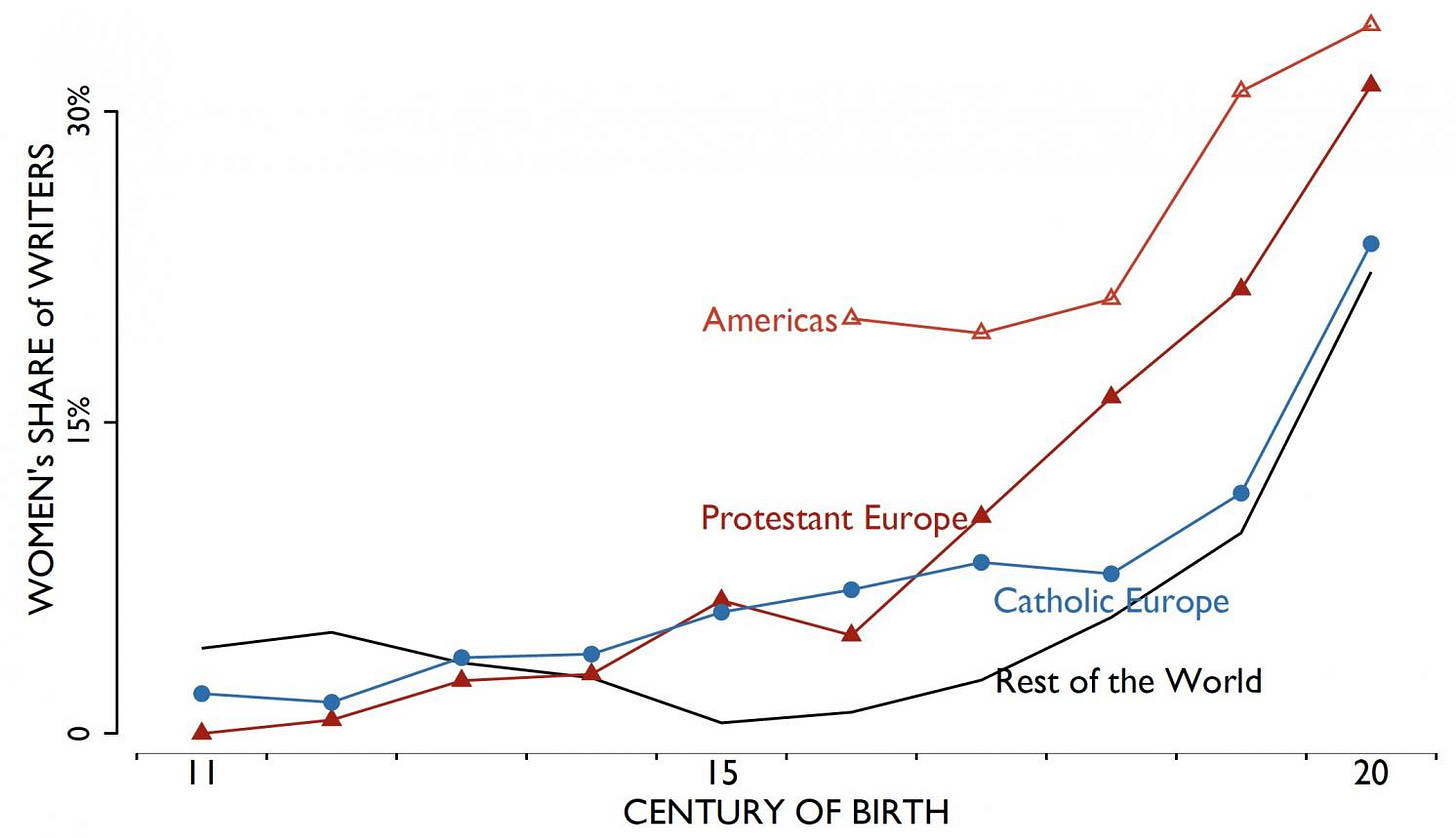

The Protestant Reformation also gave rise to women writers, who could directly communicate with a literate public.

How do they know this? By compiling a database of Wikipedia biographies in 292 languages, Arash Nekeoi and Fabian Sinn show that after the 17th century, Protestant Europe and America witnessed a dramatic surge in female authors.

Women Writers Celebrated Romantic Love

Women writers overwhelmingly wrote about romantic love - a pattern that was no coincidence. In a time when women lacked legal rights and economic independence, they recognised that male devotion could transform women's lives. Through their gripping novels, writers like Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, and George Eliot championed a revolutionary vision where men had to prove themselves worthy through devotion and mutual respect.

Jane Austen

In “Pride and Prejudice” (1813), Elizabeth rejects Darcy’s first proposal. Instead, he must prove himself worthy. When Lydia faces ruin, Darcy demonstrates utmost devotion. He tracks down the couple in London, negotiates with the unscrupulous Wickham, and pays a substantial sum. He acts purely out of love for Elizabeth, seeking no credit or advantage, demonstrating that his pride has been transformed into devotion. This story became an instant best-seller, treasured over generations.

In “Emma” (1815), the love between Emma and Mr. Knightley grows from deep friendship, shared concern for their community, and genuine knowledge of each other’s individuality. Mr. Knightley loves Emma’s vivacity and warmth, while she values his integrity and wisdom. Intimately close, they understand and cherish each other.

“Persuasion” (1815) celebrates the triumph of love. Anne’s initial rejection of Wentworth, made out of duty to her family, nearly costs her happiness. When given a second chance, she chooses love. The novel vindicates her choice - their reunion represents the triumph of authentic feeling.

The Brontë Sisters

“Jane Eyre” (1847) was truly extraordinary, possessing a firm understanding of her own consciousness and independent prerogative: “I am no bird; and no net ensnares me: I am a free human being with an independent will.” Moreover, “I do not think, sir, you have any right to command me, merely because you are older than I, or because you have seen more of the world than I have; your claim to superiority depends on the use you have made of your time and experience.” She only accepts Rochester after his first wife has died and he offers a partnership of equals. This mutual acceptance and equality allows Jane to declare, “Reader, I married him”. The onus is on her agency.

Not all readers were convinced, however! Literary circles were overwhelmingly male-dominated and often sexist. Writing in the North British Review, James Lorimer found Jane Eyre “hard, and angular, and indelicate as a woman”. Yet G.H. Lewes in Fraser’s Magazine celebrated precisely these qualities, praising “the strong will, honest mind, loving heart, and peculiar but fascinating personality”. Stepping into Victorian culture wars, Elizabeth Gaskell was commissioned to write a biography that helped legitimise Charlotte Brontë.

“Wuthering Heights” (1847) portrays love as an all-consuming force through Heathcliff's absolute devotion to Catherine:

“Be with me always - take any form - drive me mad! Only do not leave me in this abyss, where I cannot find you! ... I cannot live without my life! I cannot live without my soul!”

Elizabeth Gaskell

“North and South” (1854-1855) starts with characters that are deeply antagonistic. Initially, Margaret sees Thornton as a harsh industrialist, while he views her as a naive southerner. Echoing “Pride and Prejudice”, she rejects his first proposal. But through repeated interactions, they gain mutual understanding and empathy. Thornton cares for her so deeply that he visits her home town, just to understand her individuality.

Gaskell was married to a Unitarian minister, who strongly supported her writing. In fact, she was not the only novelist with a supportive partner..

George Eliot

“Middlemarch” celebrates marriages based solely upon mutual understanding. Dorothea’s first marriage to Casaubon fails because he cannot offer true partnership, he refuses to appreciate her intelligence. On their honeymoon, she weeps alone. By contrast, her second husband, Will Ladislaw loves both her intellect and her moral passion. Against social disapproval, they choose each other because true love enables both to thrive.

Through her fiction, Eliot makes astute social commentary:

“A woman dictates before marriage in order that she may have an appetite for submission afterwards. And certainly, the mistakes that we male and female mortals make when we have our own way might fairly raise some wonder that we are so fond of it.”

The Power of Cultural Persuasion

Austen, Eliot and the Brontes, didn’t just write love stories - they celebrated cultural ideals. Through compelling narratives of romantic love, they championed marriages built on mutual understanding and respect.

Their success rested on 3 crucial foundations:

Families that championed independent female authors.

Technological and social changes, which expanded their audience: rising literacy rates, circulating libraries and literary magazines brought novels to middle-class homes.

Religious sanctification of romantic love and courting.

What makes this cultural revolution remarkable is how it advanced women's interests within severe patriarchal constraints. At a time when husbands could exercise unchecked authority, his love was a game-changer. Thus, in an era when women lacked rights and autonomy, these talented authors achieved something profound: they made conjugal equality appealing and aspirational. Their stories became cultural cornerstones, passed down through families as cherished inheritances, shaping expectations.

The origins of romantic love and family structures in England present a complex historical narrative that challenges simplistic interpretations. While some scholars like Joseph Heinrich suggest the Catholic Church played a transformative role by banning cousin marriages, such claims require careful scrutiny. The notion that a Middle Eastern religious tradition like Christianity would fundamentally reshape European family dynamics seems counterintuitive, especially given the cultural differences between the region of origin and the societies it later influenced.

The relationship between Christianity and societal norms appears to be more nuanced than a direct transplantation of religious principles. The Roman Catholic Church might have effectively Christianized existing Roman practices rather than introducing entirely novel concepts. The Protestant Reformation further complicated this dynamic, with Anglophone cultures developing interpretations of Christianity more aligned with their cultural contexts, symbolized by the shift to conducting religious teachings in local English rather than the elitist Latin of the Catholic tradition.

Regarding gender dynamics, the impact of Christianity seems mixed and context-dependent. While the religion's emphasis on monogamy might have elevated the status of elite Roman women, its effects on Anglo women were likely less transformative. This is particularly interesting given that Anglo societies were already perceived as having relatively more egalitarian gender relations compared to some contemporary cultures. The religious narrative of romantic love and family structure appears to have interacted with, rather than completely reshaped, existing cultural norms about gender and relationships.

What a great find on Substack! I was just thinking about opting out of the app especially as I was rather ‘done in’ by the ‘stuff’ about the US election and its aftermath! Say no more. I shall look out now for more interesting and exciting things on this site….. thanks a lot for raising the bar!