Patriarchal Resurgence in Central Asia

Alarm bells have been rung about the resurgence of patriarchal ideals and demand for Political Islam in Central Asia. The Soviets institutionalised secular education and high female labour force participation. So what explains the rise of religosity, veiling, calls for female obedience and Shariah?

Here is my analysis of the available evidence:

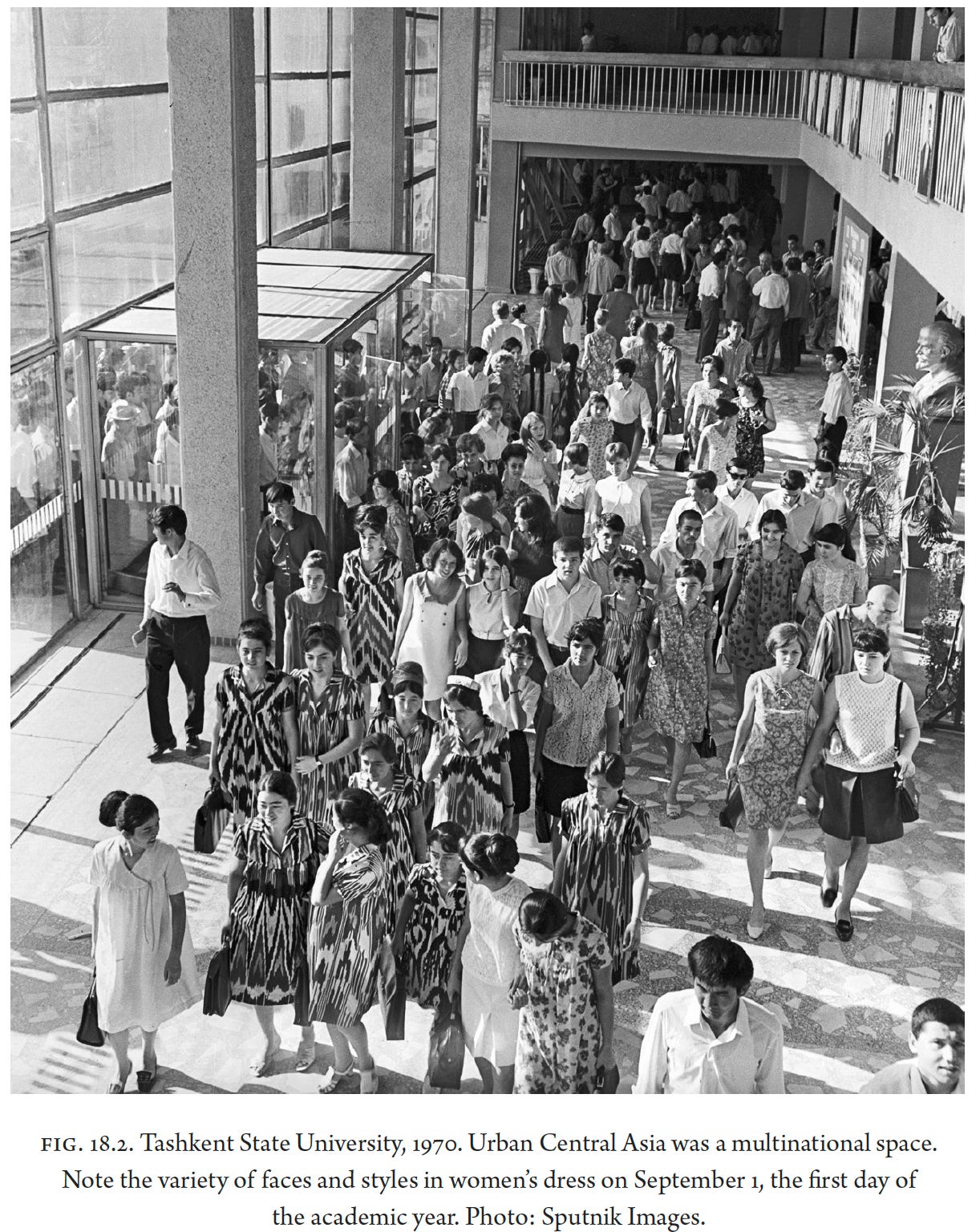

In Soviet cities, Central Asian women did gain new economic opportunities, freedoms and status.

Village life was the norm for most. Soviet penetration was weak. Religion and patriarchy persisted. Neither were dislodged by collective farms.

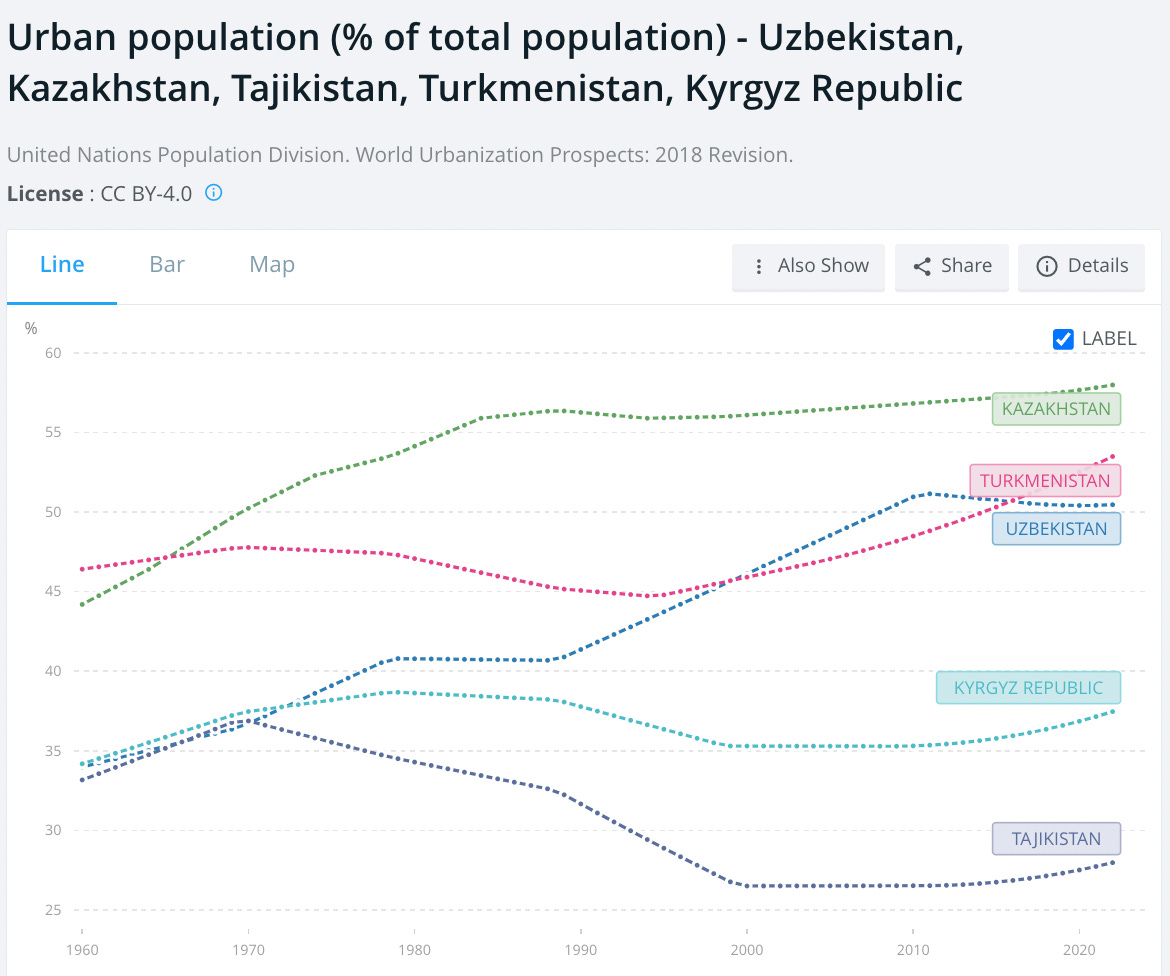

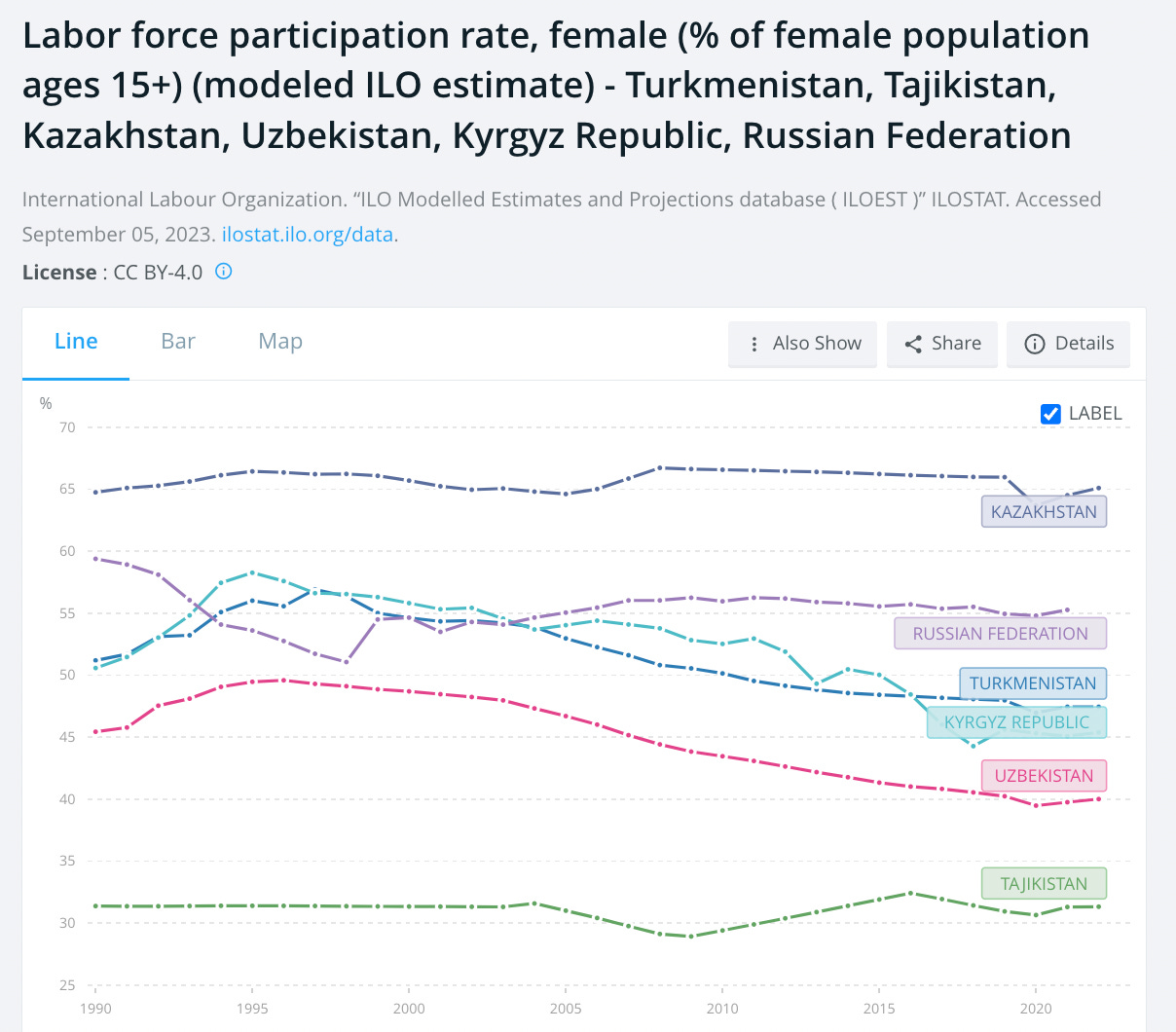

Job-creation has since been meagre. Many are still trapped in precarity - keen for the community and righteous purpose provided by religion. Economic stagnation may have perpetuated ‘zero sum mentalities’, in which men resent women’s encroachments. Oil-rich Kazakhstan bucks this trend (and continues to become more gender equal).

Transnational finance for conservative ulama. Saudi Arabia and others have championed patriarchal interpretations of Islam by funding mosques, foundations and religious entrepreneurs.

1) In Soviet cities, Central Asian women did gain new economic opportunities, freedoms and status.

Under the Soviets, Central Asia was brutally transformed. Directives were clear: local cadres would be rewarded for delivering the Plan, regardless of the human costs.

In cities, girls and boys studied together, in secular schools. Veiling was prohibited. Girls were strongly encouraged to join performing arts and competitive team sports.

Capital investment was tripled - with targets for productivity and female employees. Power stations, hydroelectric dams and railroads accelerated industrialisation. Cotton could now be processed in textile factories. Between 1925 and 1939, Uzbekistan’s female workforce leapt from 9 to 39%. To maximise female employment, the Soviets also established pre-schools - building over two thousand in Uzbekistan by 1940. Women graduated as doctors, lawyers, and scientists.

Female pioneers were celebrated - in novels, magazines and Soviet ceremonies. Basharat Mirbabayeva - Uzbekistan’s first female train driver and parachutist - was front page news. This was a ‘real revolution in life, in customs, in the minds of people’ - wrote Jabbarli in 1931.

Central Asian women attest to inter-generational cultural transformation:

“I felt I was the luckiest girl in the whole world. My great-grandmother was like a slave, shut up in her house. My mother was illiterate. She had thirteen children and looked old all her life. For me the past was dark and horrible, and whatever anyone says about the Soviet Union [now], that is how it was for me” - secondary school teacher in Tajikistan.

“[My mother] never put down her charshaf [chador].. She remained illiterate… “[But] we ourselves felt conscientious about our work. In those days it was regarded as usual that whether you were a boy or a girl, once you finished school you would gain some training and have a career.. From 1931 to 1932 all the schools became co-educational. We met with boys, at lessons, after school clubs, in the communal yards, everywhere we did things together. Later when we were at university or at work, if our male friends came to the house our mother may hide from them, but we considered that amusing” - Pusta, an ophthalmologist from Baku, born in 1921.

“I will be seventy soon. I know a thing or two about the deprived Kyrgyz woman’s civil rights before the revolution... I have gone through that humiliation. It was disgusting. When I was a fifteen-year-old girl, I was sold in marriage to a rich old man. However, my life has been changed. I have received the most supreme award on earth: Lenin’s Order, and a gold medal of the Hero of Socialist Labor. I have been serving my country as a Deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR for seventeen years” - Zuurakan Kainazarova, beet-grower.

2) Most lived in villages, which were strongholds of religion and patriarchy.

65% of Uzbeks and Tajiks in the 1960s lived in villages. That’s the same percentage rural as contemporary South Asia. State penetration was weak; religion and patriarchy persisted.

The above quotes about inter-generational cultural transformation are real, but not nationally representative.

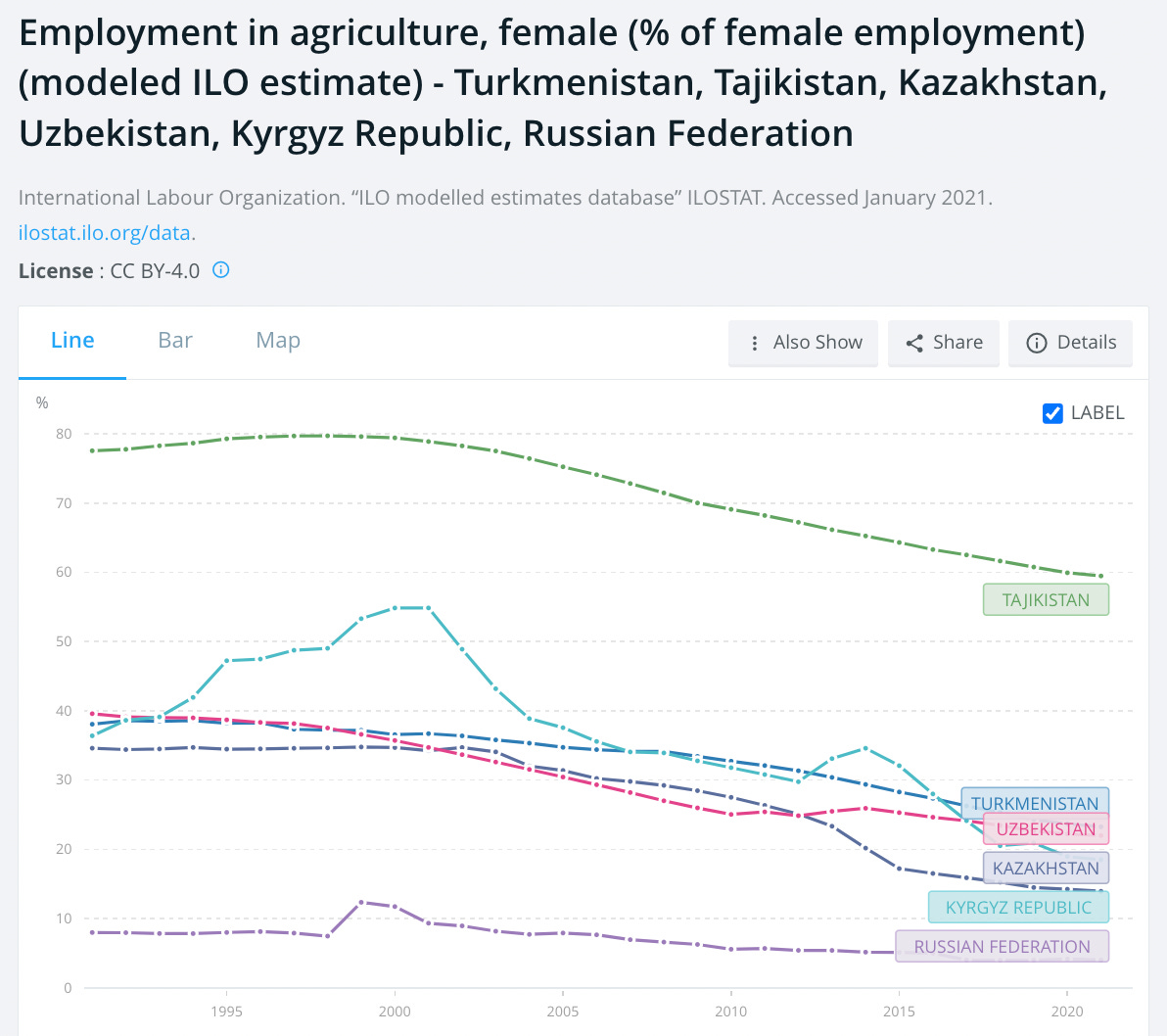

In 1990, less than half of Uzbek women worked, of which 40% were in agriculture.

Farm work does not enhance women’s status.

Women gain status when they collectively demonstrate and publicly affirm their equal competence in socially valued domains. But farm work is just drudgery. It does not enable women to gain economic autonomy, expand their social networks, discover more egalitarian ideologies, or become emboldened by collective resistance. It does not dislodge patriarchal beliefs that women should serve and obey.

In cities, religion was brutally repressed. But the Soviets lacked coercive control over the countryside.

In Soviet Tajikistan, rural women kept faith alive - organising circumcision rituals and fasting for Ramadan. When Khruschev travelled through the countryside in 1953-54, he saw strong religosity as a barrier to female employment and modernisation. Early marriage, bride price and veiling persisted in rural areas. Local Tajik officials were said to be complicit; they enforced seclusion. Soviet reports detailed that rural women were not allowed to welcome guests, or interact with unrelated men.

Respect for elders, family and community remained cardinal on collective farms - which gained legitimacy by adhering to custom. Socialising was sex segregated.

The countryside thus remained religious and patriarchal.

Post-Soviet Central Asia’s slow growth & high corruption

Central Asia’s secular authoritarians have lost legitimacy due to low economic growth, corruption and brutal repression. Uzbeks, Kyrgyz and Tajiks vent their frustrations with perceived injustice, especially corruption and repression.

People tend to support democracies if they live in a democracy that provides economic growth, peace, stability and public goods. By the same logic, successful secular regimes may breed their own support. But in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgzstan, secular authoritarians have failed to deliver.

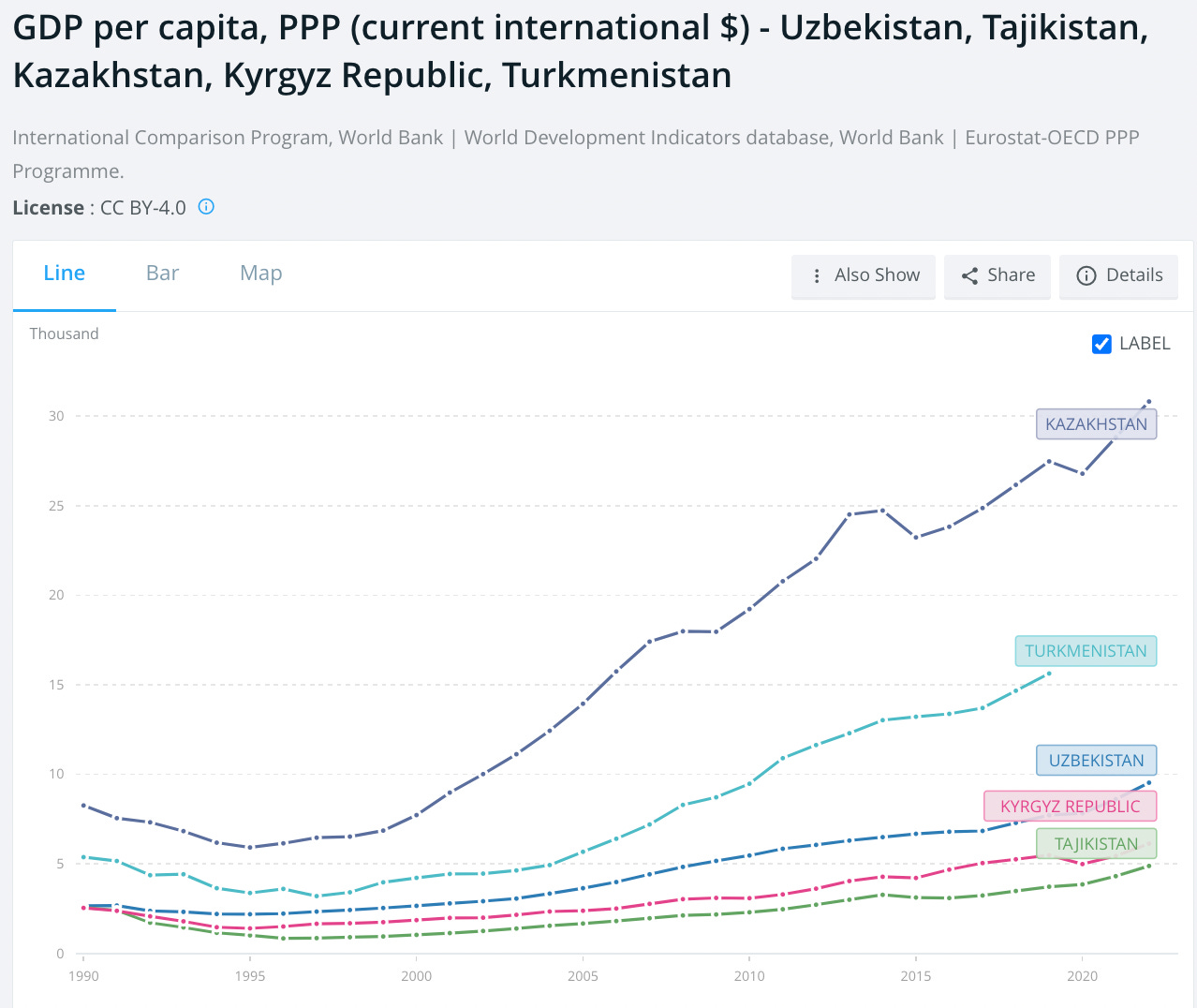

Between 1990 and 1995, Kyrgyz incomes halved. Inflation sky-rocketed. This was a massive economic shock. Precarity remains pervasive in Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Three quarters of Kyrgz men working outside agriculture are employed informally. Most Uzbek men and women lack social security.

Perpetual risk of penury can motivate demand for religious communities, which provide mutual insurance and valuable club goods. In the absence of social protection, people may turn to religion. If people feel scared, alone, and ill-served by the state, they may turn to the ulama. Publicly demonstrating piety signals commitment and helps secure inclusion (as shown in Brazil). Religion offers closeness with the divine, a sense of righteous purpose, member-only benefits and social approval. Religious rituals foster group-bonding and community.

Amid corruption, Shariah law promises fairness (backed by the threat of supernatural punishment). Political Islam retains an image of purity. Kyrygz women insisted:

“Police and the courts have no conscience. They show no justice… In an Islamic state there is justice” (Collins 2023)

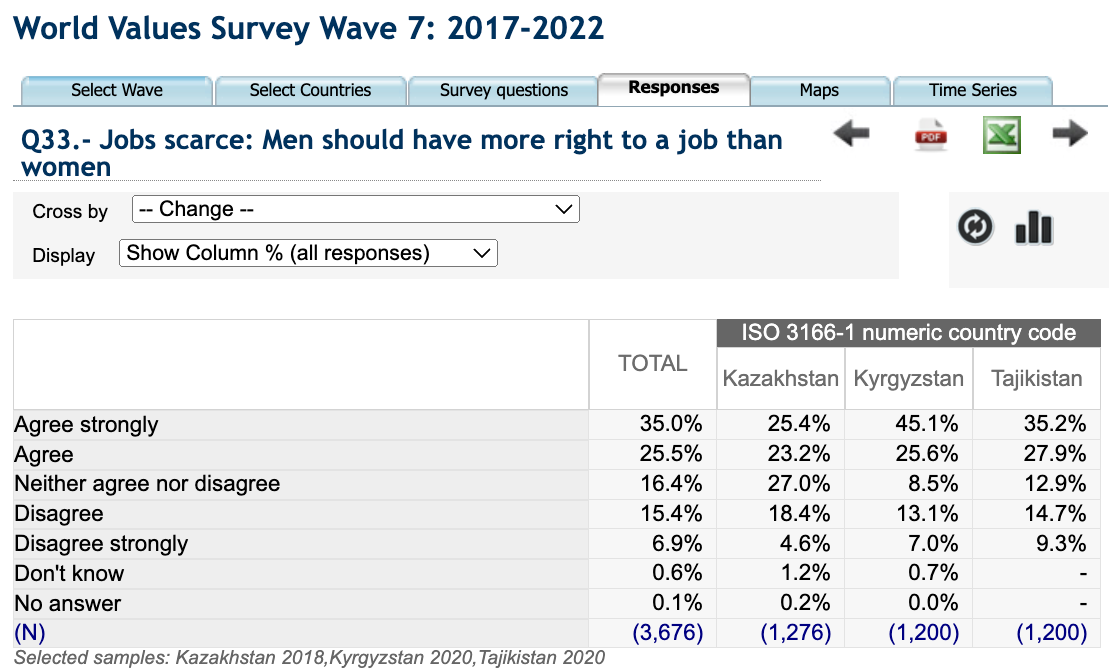

Economic stagnation may have fostered beliefs that the world is ‘zero sum’. If prizes are scarce, then one person’s victory comes at another’s expense. In Kyrgyzstan, 70% say that men have greater rights to a job. Men want to protect their rights to finite resources. Construction workers in Termiz (Uzbekistan) say that men are superior to women, who should stay out of many jobs. Meanwhile, mothers remain dependent on their sons, and seek obliging daughters-in-law. Precarity may help explain demand for strict religious conservatism.

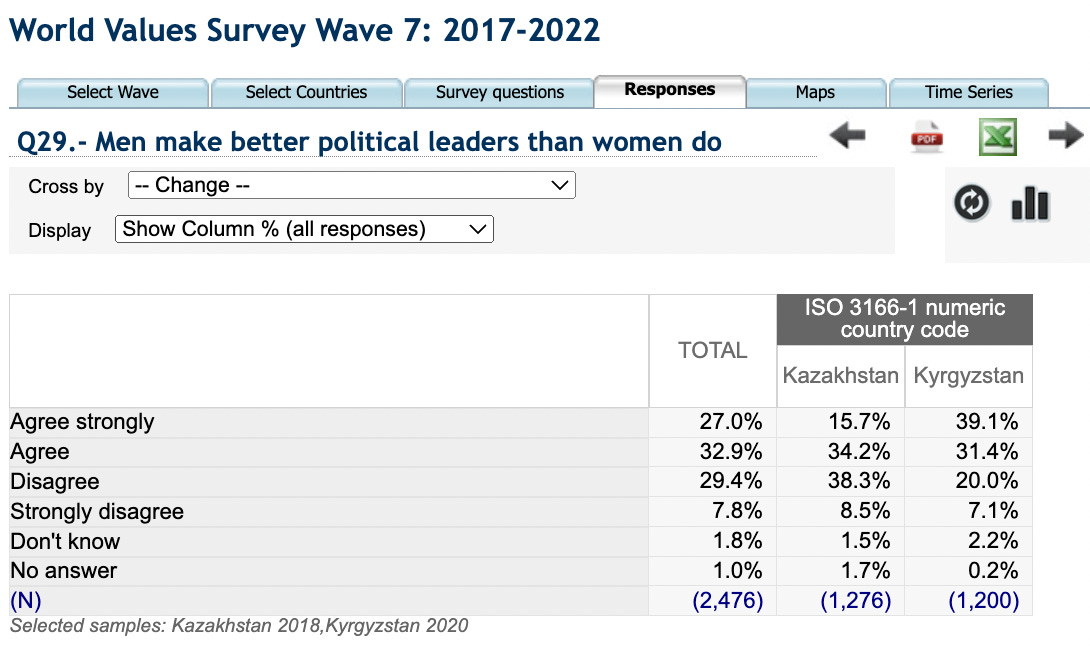

Kyrgyzstan and Kazakstan are good comparators. Both populations were nomadic pastoralists, who experienced totalitarian communism, and have since diverged economically. Kyrgyzstan remains much poorer: Political Islam has flourished; weddings may now include sex-segregated spaces; endorsement of male leadership has actually increased.

Oil-rich Kazakhstan has experienced rapid economic growth. Incomes have tripled, over the past two decades. Today, Kazakhs are half as likely as Kyrgz and Tajiks to say that religion is “very important”. They’re half as likely to say religion must be taught to children. Only 10% favour Sharia law. Women now earn a third of total labour income. Between 2011 and 2017, the share of Kazakhs strongly agreeing that men make better leaders actually halved.

Central Asia is not alone. Most Muslim-majority countries have undergone Islamic revival, with strong Arabisation. This points to global drivers.

Transnational Finance for Conservative Ulama

Saudi Arabia has promoted an extremely patriarchal and political Islam. With this funding and training, Central Asian religious entrepreneurs have mobilised the masses via cassettes, radio, and YouTube.

In the 1990s, the Government of Kyrgyzstan was relatively open to religion. Eyeing this opportunity, Saudi Arabia established numerous foundations and financed knowledge exchange. Krygz were eager for religious guidance and looked to Saudi Arabia as the birthplace of the Prophet.

Saudi Arabia also presents a strong Muslim identity against the West. While Muslims have been persecuted by their own governments, and attacked in the ‘War on Terror’, Saudi Arabia champions itself as the historic heartland of the ‘ummah’ (the worldwide community of Muslims). In Uzbekistan, interviewed young men expressed reverence for Arab and Arab-trained imams, with a ‘pure Islamic education’.

Turkey, Kuwait and Qatar have also funded mosques and foundations.

While there is great diversity across the Muslim world, and many do push for greater liberalism, Islamic thought remains dominated by conservatism.

Patriarchal Resurgence in Central Asia

The Soviets did advance gender equality in cities, but failed to culturally transform the countryside. Religious patriarchy persisted in villages. Many remain trapped in precarity - keen for the community and righteous affirmation provided by religion. Secular authoritarians, meanwhile, have lost legitimacy because they have failed to deliver. Economically struggling men resent women’s economic incursions, and use scripture to legitimise their primacy. Saudi Arabia has capitalised on this demand for Islamic revival by using its oil wealth and historic legitimacy to fund religious entrepreneurs, who promote strict conservatism worldwide.

Comments and correctives are always welcome.

I remember reading somewhere that Bangladesh banned foreign funding for non profit education many decades ago. So you think this is one of the reasons why Bangladesh has remained RELATIVELY secular than other Muslim countries of comparable wealth. Although migration into the Gulf countries for jobs has probably offset the benefit of the ban as these people learn political Islam from their Pakistani peers.

Yes that’s true. Russians left. But Kazakhs are still relatively gender equal