Paternity leave (in feminist Spain) promotes gender equality among children. This may be due to changes in men's brains

In 2007, the Spanish government introduced 2 weeks of paternity leave. A fantastic new paper by Lídia Farré, Christina Felfe, Libertad González and Patrick Schneider finds that children of eligible fathers are now much more gender equal. Why might this be?

I suggest that Spain’s post-Franco secular backlash and relentless feminist mobilisation have pushed inequalities to the forefront of public conversations. Widespread endorsement of feminism accelerates cultural change because egalitarians anticipate social support. Spanish fathers overcame the coordination failure that elsewhere suppresses uptake of parental leave. Their children are now much more gender equal. Drawing on new work in neuroscience, I suggest Spanish fathers’ bonding with their babies promoted long-run care-giving.

60% of Spanish fathers took parental leave

By international standards, this is whopping.

When California introduced Paid Family Leave, paternal leave uptake only increased to 3%. American fathers appear largely insensitive to leave legislation. They are only 4 percentage points more likely to be on leave if covered by legislation. In Japan, only 13% of fathers take paternity leave.

Men may be caught in a negative feedback loop, sustained by concern for economic advancement and anticipation of disapproval. If men’s over-riding fear is that employers will doubt their labour market commitment and do not anticipate any condemnation for deserting their new babies, they may remain at work.

As Noboru Hosokawa, (a Japanese manager) explained,

“I was very busy with work and thought it was impossible to take the leave,” he said. “As a manager, I needed to improve sales, and mistakenly believed that taking paternity leave would undermine my image among my subordinates.”

Japanese men actually underestimate wider support. Since other men rarely take leave, onlookers presume it is widely opposed, and are thus reluctant to deviate unilaterally. This is a coordination failure. American men are also less likely to take leave if they anticipate stigma. Worries about seeming uncommitted deters men’s use of family policies.

What keeps Silicon Valley tech bros away from their babies? How did Spanish men overcome this negative feedback loop?

Let me share two hypotheses: feminist activism and welfare entitlements

(1) Overcoming coordination failure through feminist activism and public conversations about equality

After Franco’s death, Spain underwent a secular backlash. The Church had been totally discredited by association with authoritarianism. Spaniards came out in droves, to dismantle Catholic taboos and celebrate sexual liberation. Female employment, activism and representation have since soared. Spain had the world’s first female-majority cabinet. In 2018, five million joined a ‘feminist strike’ against machista culture. In Barcelona this year, 40,000 people marched for International Women’s Day. Feminism is also embedded within government bureaucracies. Barcelona’s City Government carefully monitors ‘the democratisation of care work’.

As you can see from David Rozado’s comparative analysis below, Spanish media has paid especially high attention to ‘sexism’.

Spaniards are exceptionally keen to identify as feminists (even more so than Swedes!). Massive marches and public endorsement of feminism accelerate cultural change, because onlookers anticipate broad approval.

(2) Widespread acceptance of welfare entitlements

Compared to Germans, Spanish people are more slightly likely to endorse state responsibility and individualistic exploitation of welfare systems. So here’s an alternative hypothesis: if fathers are entitled to a benefit, maybe they take it.

I don’t know the answer, I merely share these as two possible explanations.

Given widespread support, Spanish fathers eagerly took advantage of new entitlements. Widespread uptake may have reinforced a positive feedback loop in which paternal leave became both widespread and socially expected. Whereas in Germany - where very few identify as feminists - paternity leave legislation had zero impact on men’s share of care-giving.

Does this endogeneity invalidate Farré and co-authors’ research design?

No.

To study the intergenerational impact on gender norms, Farré and co-authors use a difference-in-differences approach. Collaborating with 16 schools in Catalonia, they surveyed and ran a lab-in-the-field experiment with 11-13 year old children, born around the cut-off for paternal eligibility. Since feminist conversations have been ongoing for decades, their approach seems totally legitimate.

My only caveat is that we should not expect legislation to have similar effects elsewhere without a commensurate rise in feminist activism or attitudes to welfare.

Children of eligible fathers are much more likely to endorse gender equality and share housework.

The share of children perceiving it as socially “appropriate” or at least “fairly appropriate” that a mother works increases by 18 percentage point. Boys born after the cut off are 15 percentage points more likely to do female chores. This is ginormous.

As the authors note, awareness-raising initiatives have a far weaker impact.

The fact that paternity leave can engineer an intergenerational shift in norms is hugely important. In North America and Europe, men’s lesser share of care work is a major obstacle to gender equality. Upon motherhood, women tend to take a step back from the labour market and pursue jobs with greater flexibility. High-paid, prestigious positions thus remain dominated by men.

What are the precise causal mechanisms?

The authors do not speculate. But let me offer a hypothesis, drawing on the latest work in neuroscience.

Martínez-García and colleagues ran MRI scans on a small sample of Californian and Spanish men’s brains before and after parenthood, as well as childless men. Men’s brains change upon parenthood, in ways that promote care-giving. Curiously, the Spanish sample of men showed a much larger volume change in dorsal attention. The authors speculate this was because uptake of paternal leave enabled Spanish fathers to spend more time bonding with their babies.

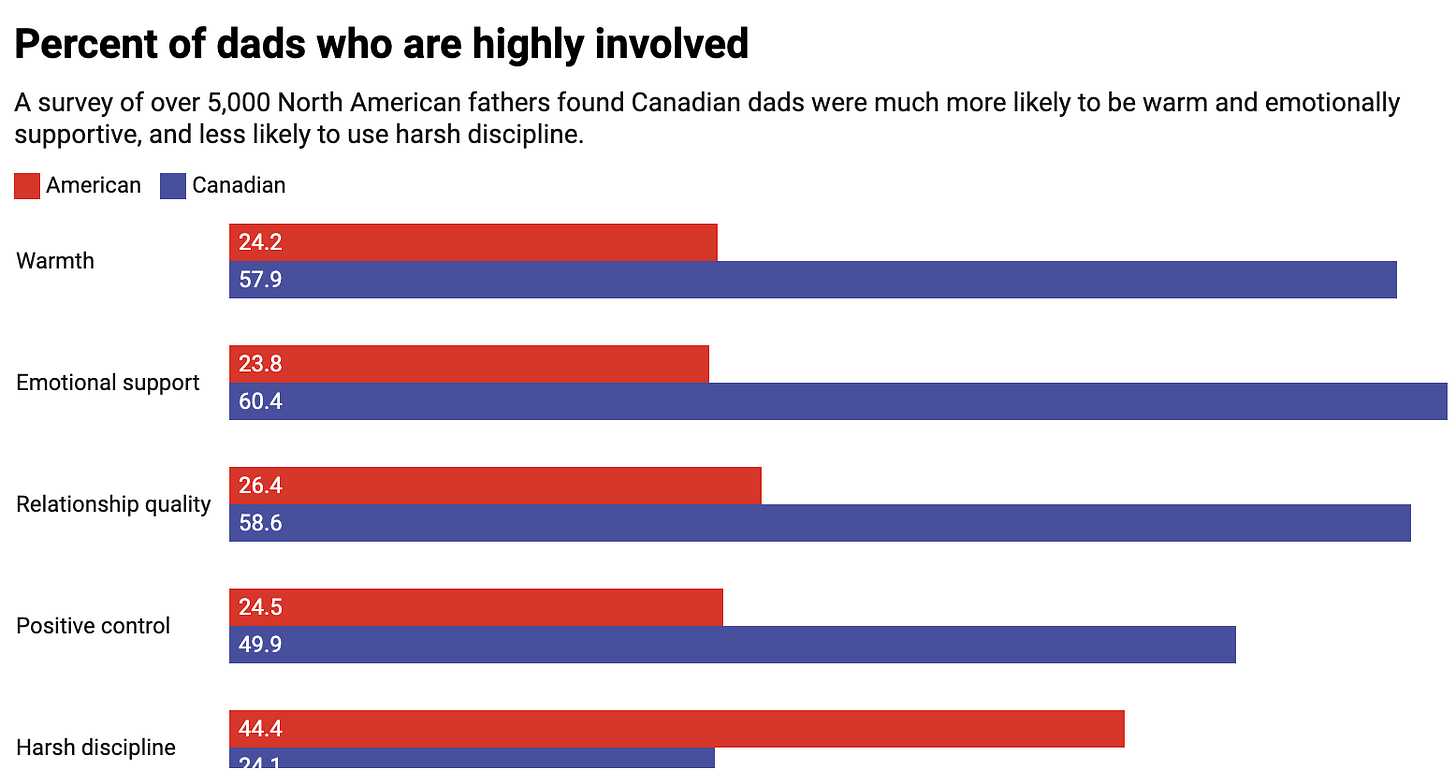

I would be curious to see more cross-national comparisons of men’s brains. Canada, for example, has paternity leave legislation, public conversations on care, and high paternal involvement. Compared to Americans, they’re more likely to provide warmth and emotional support. Has paternity leave changed their brains?

TLDR:

Men are trapped in a negative feedback loop, reluctant to take their paternal rights for fear of public disapproval. Spain’s feminist activism and government legislation nurtured an environment where fathers felt comfortable to spend time with their newborns. Those children then became radically more likely to endorse gender equality and share housework.

This is pretty weak argument, imo. The brain change is an aftermath of involvement not the causal reason why that happened. You are mistaking causality for mediating factors, presumably what this may imply is other men has evolutionary/genetic potential to be so! Unless you subscribe to genetic determinism but you don’t since you identify men’s perception as the factor implicitly here. In the case of children’s cultural change, one may ask what better ideology will a child subscribe to than what’s available in their family/society? The causality in children is with blind beliefs granted after birth, with men it seems to be an outcome not of some abstract policy making, conversations (think as you made in one post ab impact of advices in obesity/HIV) nor leaves themselves (as in the American ex provided), but something else in the environment. This fails to tackle what that is here and I don’t know clearly what that is either.