Economic Precarity & Cultural Persistence

Does economic insecurity generate an intrinsic or instrumental desire for conformity? And does this relationship hold universally?

Why have some countries undergone rapid cultural change, while others are marked by persistence? And why does social norm policing often revolve around gender?

One key mediating factor is the great economic divergence. Some countries are now rich, while others remain poor. In places with weak job creation and chronic precarity, people remain heavily dependent on kinship networks. Men maintain inclusion in vital networks by ensuring their families conform to established strictures. Fear of social exclusion motivates an instrumental concern for approval.

Insecurity and instability - exacerbated by conflicts and ecological threats - may also generate intrinsic desires for group conformity and norm enforcement.

Economics is not the whole story, however. Latin America and MENA have undergone similar growth trajectories, yet Latin Americans have become considerably more liberal, secular and supportive of gender equality. Precarity thus only partly explains cultural persistence.

Obedience secures trust and favouritism, from both employers and kin

My argument that insecurity reinforces dependence on kin, which in turn motivates tight conformity, echoes Daron Acemoglu’s theory of how labour market expectations shape parenting. He argues that “in low-wage environments, low-income families impart values of obedience to prevent disadvantage in the labour market”. Fearing unemployment and long job queues, working-class parents teach their kids to obey in order to maintain their employers’ favour.

Acemoglu’s theory about courting employers is equally true of kin. He argues that “Obedient workers are less likely to deviate from the rules imposed on them by their employers, and hence require a lower efficiency wage premium”. Yes indeed! People prefer to do business with those they can trust. That’s precisely how kinship works. As Henrich observes, families may patronise their uncle’s shop, even if it is neither the cheapest nor the best quality. Workers and sellers are able to out-do market competition if they can offer unparalleled trust. Kinship networks then act like monopsonist employers, providing vital lifelines amid chronic precarity.

How economic under-development breeds cultural persistence

Most Indians remain trapped in agricultural or informal, small-scale employment. They lack regular pay cheques, let alone insurance against unemployment and workplace injury.

When Indians need help, support, access to raw materials, markets, loans, or jobs, they often turn to their trusted caste network. Insiders have long derived great benefit from their jati and strengthened trust through endogamous wedlock. Caste panchayats (assemblies of older men) built trust in caste networks by overseeing women’s sexuality and reproduction. If a woman rejected her arranged marriage, the caste panchayat might severely fine her family or even outcast them: prohibiting future marriages, cutting off their social networks, and sources of mutual insurance. An entire lineage could be alienated and expelled from the village because of one daughter's misdeeds. Punishing (women’s) deviation builds trust within jati. Out-marriage is only 5% in rural India: an eloquent indicator of the persistence of traditional networks.

India’s cities (especially the smaller ones) are thus rife with caste-based residential segregation. Segregation by caste is actually more widespread than segregation by socio-economic status. Ambedkar famously decried the village as ‘a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness and communalism’. Yet thanks to South Asia’s pattern of economic development, those same institutions have been transported to the cities.

“Everything is so dependent on social relations: contacts, helping each other, solving problems, capitalism is so entrenched in social networks, these are built through reciprocation of favours, attending each other’s events and buying gifts. We still need that community. This is why we have all these annoying aunties when you are getting harassed” – Pooja, Haryana.

In India there is a lot of fear and anxiety. If you rock the boat, you’ll be poor. If you speak out you’ll be a social outcaste. They don’t want to face the consequences of going against the grain” – Aanya, Mumbai.

[excerpts from my qualitative research in India]

Arab economies, meanwhile, are segmented into insiders and outsiders. Insiders benefit from state protection, contracts, subsidies, licenses, and land. Outsiders remain trapped in precarity. Economically, this retards private sector job creation; small firms struggle to grow and remain largely family-based.

Arabs continue to rely on wasta. Social connections are necessary to access jobs, secure permits, avoid trickery, and resolve conflicts. Even middle-class, professional Jordanians acquire social insurance from kin.

Inclusion is contingent upon maintaining trust and family honour, which is easily damaged by rumours of female impropriety. Marriages are the lynchpin of kinship networks. Since brides marry into men’s families, they are socialised to please their in-laws and preserve marriages at all costs.

Loyalty is culturally esteemed: girls are encouraged to put family first, police themselves, and protect family honour. ‘Good girls’ learn to stay quiet. Fear of expulsion from kinship networks motivates families to school women for subordination and enforce endogamy. Divorce is so intolerable that Indian newly-weds can coercively extract larger dowries by beating their brides. Her family would rather pay up than let her leave. By suppressing dissent, kinship networks remain intact.

Does precarity create an instrumental or intrinsic desire for conformity?

Acemoglu theorises that working class parents instil obedience in order to advance their children’s economic prospects in low-wage environments. Their motivation is instrumental.

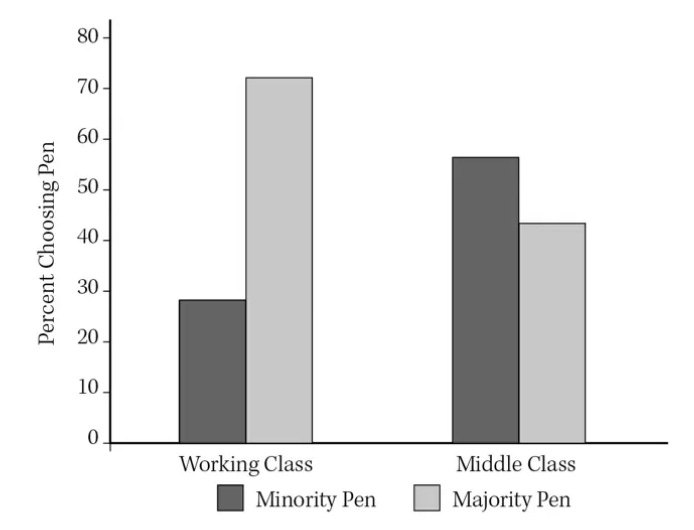

Michele Gelfand and co-authors suggest an alternative hypothesis. Insecurity and instability - exacerbated by conflicts and ecological threats - may generate intrinsic desires for conformity and norm enforcement. Working-class Americans - who often work in dangerous jobs, worry about making the rent, and have little social security - tend to extol obedience and authoritarianism. Their moral codes seem to extend beyond employment. When given a choice of pens (4 green, 1 orange), 72% of working class participants chose the majority colour. They valued conformity.

A wider body of evidence suggests that when people feel under siege, they may seek strength through unity, want norm violators to be punished and increasingly conceptualise God as punitive.

Earthquakes seem to increase religosity, especially among districts rarely hit by earthquakes. Pakistanis whose homes were completely damaged by an earthquake were much more likely to be religious.

Unemployment may also compound anxiety and insecurity (as famously argued by Richard Layard). Brits who grew up in areas with high unemployment are now more conservative on gender.

Unemployment also soared in 1970s Egypt. Failing to secure white collar work, many graduates found solace in religion. They turned to the Muslim Brotherhood. Clerics declared the economic and military failures of the state to be punishments for aping the West. Men sought to restore order by demanding veiling, harassing women in the streets, and enforcing patriarchal dominance.

If scripture reveals God’s word and deviance is met with eternal punishment, it becomes rational to impose strict regulations. Without a culture of dissent, sacrosanct teachings go unquestioned. Piety then becomes necessary for social approval. Pakistani Facebook users who pray daily and endorse religious absolutism are more likely to think that men have the right to beat their wives.

Germans exposed to terror attacks are more likely to vote for the far right, especially if they’re less educated and politically active. This holds even though 75% of attacks are by the far right. After terrorist attacks across Europe, German Twitter users also adopted the language of the far-right. ‘Immigrants’ and ‘Muslims’ become more common. This shift in language is correlated with more votes for the far right.

None of this happens automatically or mechanically. Humans are not robots. Everything is up for grabs and subject to ideological persuasion. But there is at least some evidence that organisations preaching obedience increase their followings under conditions of insecurity.

Does precarity increase an instrumental or intrinsic desire for conformity? Based on the available data, it seems hard to say. Both Acemoglu and Gelfand may be right.

Economic under-development does not entail cultural conformity

Latin America and MENA have similar economic growth trajectories. But Latin America has undergone rapid cultural change. This includes rising secularisation, female employment, feminist activism, and representation. Economic precarity does not therefore deterministically entail social conformity.

During my interviews in Mexico City, Puebla, Cholula, Atlixco, Oaxaca city and Tlacolula, people emphasised that historically strong concern for social approval has considerably weakened. Sofia (a 55 year old cleaner, working in a love motel) encapsulated growing individualism.

‘We [women] are always criticising. We always eat each other. “You see how she is dressed? Showing her legs, very provocatively”. Sometimes they criticise you talking to a man, not knowing it’s a relative. People talk about it, but people aren’t going to give you anything to eat. They’re always going to talk about it, whether you [a woman] are working or not working. I don’t care what they think, as long as I know I do the right thing and ask nothing of them.

“When my daughter was a teenager and went to university, she wore what she liked. I said to my daughter, “you have the right, the times are changing, just take care of yourself. Tell me who you are going with and what time you arrive”. They have to learn in life what is bad and what is good. You interact with people and learn how to take care of yourself.

I wish my daughter had been married. But it was her decision. I did not force her. I told my daughter, “it’s your decision whether you want to get married or not. I cannot oblige”. Previously we were forced to marry, because they worried what people would think, but not any more. Some [formal marriages] divorce after a year [i.e they are not effective]. [Cohabitation is okay] as long as they know how to understand each other.

I don’t care what people talk about me or don’t talk about me, as long as I know I’m not doing anything wrong, and I’m right. If people care about you it’s because they appreciate and love you, but if they do not appreciate you, they do not care what happens to you”.

(translated from Spanish, using Microsoft Translate)

Again and again, my Mexican participants emphasised that concern for gossip had radically weakened. The reasons for Latin America’s cultural change require another Substack, but for now let me just share this as evidence that economic under-development does not mechanically entail cultural conformity.

TLDR

Humans are incredibly inventive. In some cultures, they mitigate precarity through close-knit reliance on kin, which in turn motivates strict conformity. Insecurity may also generate an intrinsic desire for normative policing. Both mechanisms often revolve around control of women’s bodies. But neither are inevitable. In Latin America (though less so MENA) there has been radical cultural disruption and growing gender equality.