Is Pakistan becoming more Patriarchal?

Over the 20th century, the entire world became more gender equal. Or so I thought. But Pakistan has rocked my priors. Female employment has slightly risen. Meanwhile, young Pakistani women are more sexist than their grandmothers. What is going on?

Female employment is well below the global average - in Pakistan, Bangladesh and India

Women are far less likely to participate in the labour market than women in similarly wealth countries. This was true in both 1995 and 2019.

Although Pakistani female labour force participation is low, it has risen slightly.

Punjab is Pakistan’s most densely populated province. Women rarely work outside agriculture. The overwhelming majority of Punjabis are also strongly opposed to female leaders, and in some villages there are restrictions on female voting.

Across Pakistan, women report major restrictions

Only 30% of female respondents to the 2013 Labor Skills Survey said they could go to local markets or health clinics alone. One fifth of women reportedly never go to the local market. Women who are not allowed to venture outside the home are also much less likely to work.

Fear and discrimination constitute further impediments. Most Pakistani women say they do not feel safe in public places. Surveyed Pakistani firms have usually expressed strong resistance to hiring women.

Female labour force participation has risen, slightly

Even though Pakistan remains extremely patriarchal, gender gaps in labour force participation have actually fallen. In every province, rural and urban women are now more likely to work. This indicates that restrictions are loosening.

In rural Pakistan, women of all levels of education are much more likely to work. In towns and cities, employment has risen amongst university graduates. Skilled employment is both better paid, culturally esteemed and psychologically rewarding.

Is Pakistan becoming more patriarchal?

Even though female labour force participation has slightly risen, young Pakistani women appear much more sexist.

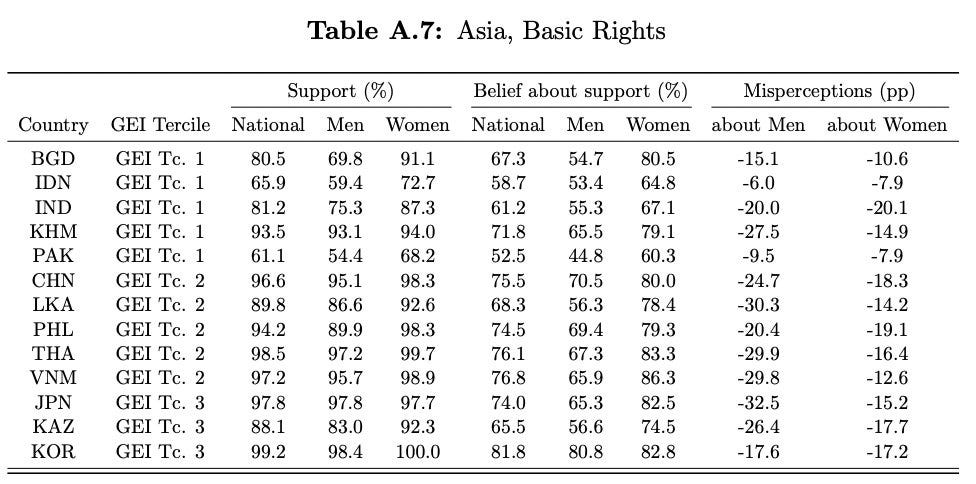

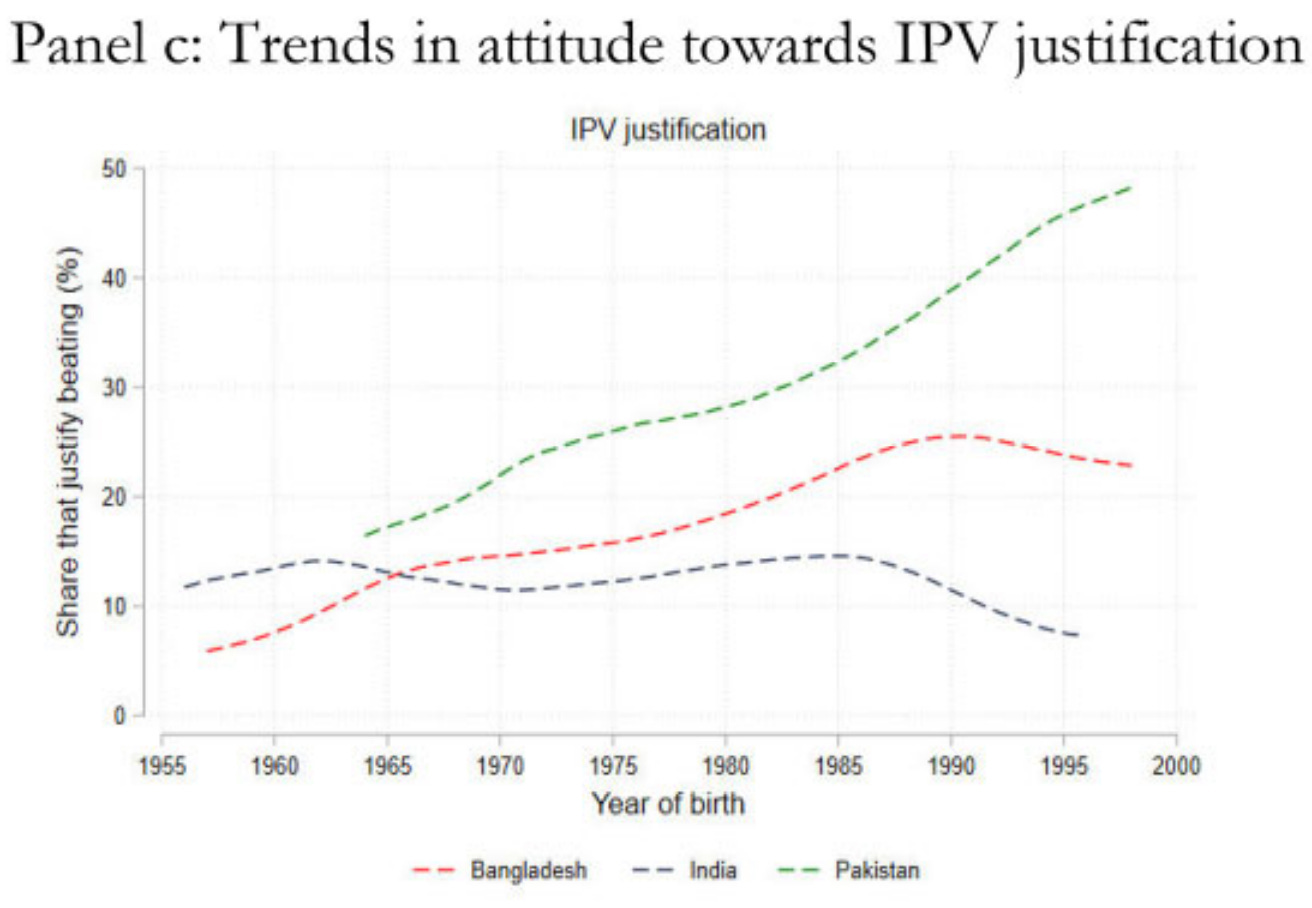

Intimate partner violence is more justified by the young

Wife-beating is justified by almost half of young women in Pakistan - find Bussolo and colleagues. Grandmothers are much more opposed. This bucks a global trend, since younger generations are usually more supportive of gender equality. In neighbouring India, attitudes are at least stable across generations.

“When jobs are scarce, men have more right to a job”

The overwhelming majority of young Pakistani women say that when jobs are scarce, men have more right to a job. Compared to their grandmothers, young women are actually more sexist.

Hostility is corroborated in a recent survey by Leonardo Bursztyn and colleagues. Only 54% of Pakistani men say that women have the right to work outside the home.

“University education is more important for a boy”

60% of young Pakistani women say that university education is more important for boys. Only 40% of their mothers’ generation concurs.

“Both partners should contribute to household income”

Pakistan is in deep economic crisis. But younger people are far less likely to say that both partners should contribute to household income.

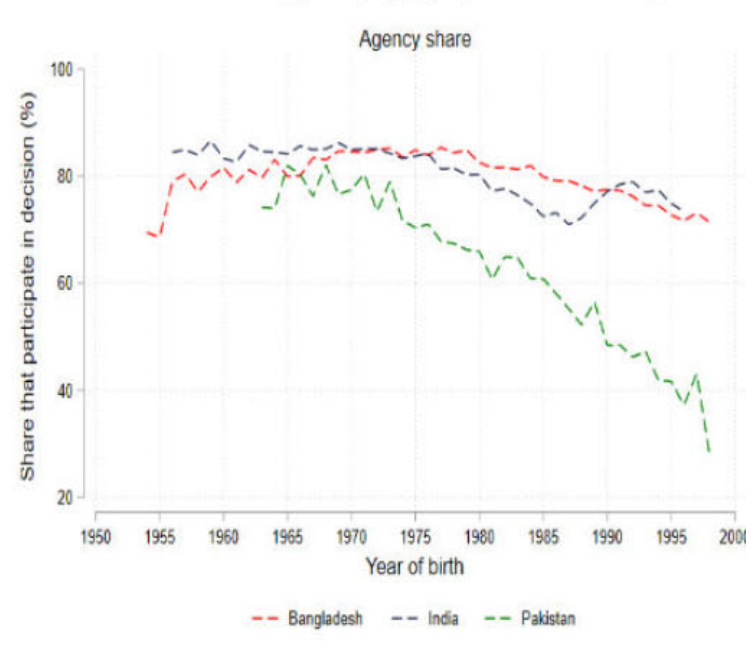

Women’s participation in household decisions

The vast majority of young Pakistani women say that they have no say in household decisions, their preferences are overlooked and ignored. Whereas in India, women of all ages usually have their say.

Is Pakistan becoming more patriarchal?

Something unusual is clearly going on in Pakistan.

On the one hand, female employment has risen slightly (though remains well below the global average, even compared to similarly poor countries). On the other hand, younger women are more likely to justify wife-beating, endorse male bias, and say their preferences are ignored.

We lack panel data on attitudes, so it’s impossible to say whether Pakistani youth are always more sexist or whether something new is impacting the current generation of young women.

Both of these trends are surprising! Elsewhere in the world, younger women are the strongest proponents of gender equality. Furthermore, rising female employment usually fosters support for gender equality. But both are flipped in Pakistan.

I share this data to motivate wider inquiry:

Are young Pakistanis becoming more patriarchal?

If so, what’s driving sexist attitudes?

Why has urban female employment slightly risen, while ideologies remain so sexist - in terms of education, employment, gender-based violence and household decision-making?

How can this (possible) trend of rising sexism be averted?

What explains the Pakistani paradox?

Hypotheses for rising patriarchy:

President Haq (1978-88) strengthened religious laws, institutions and madrasahs;

Saudi funding and labour migration has encouraged Wahhabism;

Does the incongruence of behaviour and attitudes indicate backlash? As slightly more women enter the workforce, are conservatives preaching that men have the authority to make decisions and beat their wives?

Have instability, insecurity, and economic crises fostered what Michele Gelfand terms “cultural tightening”? Threats (like neighbouring Afghanistan) may make people less culturally permissive.

Keen to understand the drivers of change over time, I’m heading to Lahore and Karachi for a month for qualitative research.

I am very keen to learn from Pakistanis. Please do email me (alice.evans@kcl.ac.uk) if you’d like to meet. Thank you!

So much to discuss from this article! Would have loved to meet you if I was back in Lahore. I grew up, and my family still lives, in a "lower-class" area of the city. Pakistan is a very paradoxical country and I often find myself checking myself when making statements about it. I wish we had more statistics that took urban/rural or economic class into account. For example, a very common story I've heard from domestic labour (house maids, cleaners etc.) is that the men in their family are not really earning or just don't earn enough so they have to do all the labour.

Some more thoughts:

There is just a very pervasive trend of Islamic conservatism in society that cuts across the economic divide. Pakistani media personalities also tend to all have a religious bent. The ones who don't have to check themselves. The most common exhortation I notice across social media is that we aren't religious enough, and our lack of religion is the main reason for the deterioration of our society. The most popular leader, Imran Khan, also had a very explicit religious bent. I'm sure this leads to what your findings say. I'm not at all surprised by them. This has largely been my anecdotal experience.

Women don't really venture out of their houses for leisure so much, yes. When you go to Lahore, you will see huge swathes of people in public areas, but exceedingly few women. This may wary depending on the place though. You will find majority women in clothing markets like Liberty Market, but rarely any in the markets of Hall Road for example. Societal expectations play a huge role in this. It's not considered "proper" for women to be out and about. My house has a small park in front of it. They even designated it a "ladies park" some time ago. I never see any ladies in it. Ugh, I can go on and on with personal anecdotes here.

Not surprised by employers not preferring women either. Men will largely keep working because they have to but there is the expectation that women often drop out once they get pregnant, or maybe their household (they largely live with the husband's family) would object one day to their working and they would have to leave their job. You will find women who've finished med school staying at home, because their in-laws don't want them to work.

This is all anecdotal of course.

Purely from observation I'd wager that FLFP is higher amongst families at either extremes of the socioeconomic pecking order. Women from lower socioeconomic classes are more likely to need the income and hence work, often in agriculture (sometimes unpaid in family farms), in factory work (textiles primarily), and as housemaids. Women from higher socioeconomic classes are typically from more liberal, elite families where the stigma of a women going to work is lessened, and where they have access to jobs deemed more 'acceptable' for women, such as office work. It’s in the in-between of these two where I'd expect FLFP to be the lowest. Again, I have no hard statistics to back this up, but I do think this is part of the explanation for the U-shaped 'FLFP by Education and Residence' Graph in your post.

I would also guess the same phenomena occurs with religiosity, where families from both the highest and lowest socioeconomic classes both display less religiosity than the middle majority. Families from lower socioeconomic classes have limited access to formal religious education, their practices are more influenced by local traditions and customs rather than Islamic teachings, so there is usually less of a rationale for them to be against their wives/daughters working. Likewise, families from higher socioeconomic classes are more exposed to western media, educated, and secular and so their men are more likely to accept their wives/daughters working, and their women are more likely to push back against attempts to limit their economic freedom. I'd guess there is a strong link between religiosity of oneself, one's family, one's community, and the likelihood of FLFP.

An anecdotal example of this; in my last visit to Pakistan a few months ago I saw only two people with tattoos – something that is incredibly taboo from a religious perspective. I saw a young woman with tattoos at a wedding in a prominent venue in Lahore, where various bureaucrats, two famous cricketers from the national team, a well-known actor, musicians, and overseas Pakistanis were present. I also saw a young guy in a barber shop with tattoos, who was clearly not as well off - there is a small subculture of urbanised youth who imitate western fashion trends, dye their hair, and even tattoo themselves. Think Mods and rockers except Pakistani – lol.

As you point out the period of Islamization under General Zia ul-Haq undeniably had a role in this. My grandmother – who was born under the British Raj pre-1947, says that growing up the Hindu and Muslim girls would celebrate each other’s Eid’s and Diwali’s. She once told me that there was nothing wrong with a Hindu girl marrying a Muslim boy, it is hard to imagine most women in Pakistan holding that view today!

One of the side effects of the arrival of Islam to the Indian subcontinent was that it severely weakened the caste system in Muslim-majority areas. In fact, some people converted specifically to escape the caste system - particularly Dalits. Sufiism is especially heavy on themes of egalitarianism. Unlike some interpretations of Hinduism, and like other Abrahamic religions, there is the notion of the equality of all believers. So, while we don’t suffer as much from the issues of caste, cultural classism is still incredibly prevalent in Muslim-majority areas such as modern-day Pakistan. It is ok for a woman that is a member of the liberal elite classes to wear western clothes, go out to malls, etc, but not for a woman of the lower classes. Being in a low-trust society with weak institutions lends itself to nepotism, corruption, and insular tribe-like communities; In Punjab a Rajput will not marry outside of their Biradari, In Sindh people will not vote for anyone outside their feudal lord’s family, Some Pashtun tribes arrange marriages within the same tribe to maintain tribal identity, etc. It also (probably) lends itself to an overly patriarchal society.

Anyways, that’s just my two cents. Have a good trip in Pakistan :)