Is joblessness fuelling hostile sexism worldwide?

Economic development promotes gender equality. But why? Does industrialisation enable women to liberate themselves from patriarchal control? Or is prosperity paramount for men’s egalitarianism? In this piece, I’ll try to persuade you of both. When upward mobility is thwarted, men are more likely to lash out at women and demand patriarchal controls. This holds across America, North Africa and possibly more broadly.

Sexual harassment goes up when American men lose work

They also tend to share abusive porn, oppose abortion, buy guns, and reject female politicians. White men retrenched in 2020 were more likely to support Trump. Backlash is most severe in communities where unemployment has disproportionately hit men. It’s also mediated by culture, highest amongst Republicans.

Men who feel unfairly disadvantaged also tend to endorse hostile sexism, e.g. “women exaggerate problems they have at work”, “women seek to gain power by getting control over men”. This resentment holds in both China and America. Across Europe, young men in places with rising long-term unemployment express stronger opposition to women’s rights.

Misogyny is not just materialist. Ever since the 1970s, the Religious Right has harnessed media networks to ignite fears, mobilise zealots and affirm their righteous resistance. Charisma and propaganda are powerful tools, but resonate most strongly amongst those stuck behind in small towns, lacking the capacity to thrive.

7 million men (aged 25-54) in the US are currently out of work.

America is not exceptional.

Unemployment has also exacerbated male resentment in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

10-15% of people in the Middle East and North Africa are unemployed. Widespread economic frustrations may have exacerbated religious revivalism, sexual harassment and calls for female seclusion.

Strict ideals of female chastity go back at least a thousand years. Persian theologians managed state institutions of learning when Iraq was the seat of the Sunni Muslim empire. Transmitting Mesopotamian and Zoroastrian influences to Islam, clerics extolled rightful patriarchs who achieved ethical perfection by cloistering their wives. Religious authoritarianism inhibited dissent across the Ottoman Empire.

Traditions are changeable, however. In the twentieth century, ambitious leaders sought to catch up with Europe by embarking on top-down economic modernisation and societal transformation. From Cairo to Kabul, educated women abandoned their veils and shortened their hemlines.

In the 1970s, disruption ground to a halt. Unemployment soared. As Egyptian graduates increasingly struggled to secure white collar work, they found solace in religion. They turned to the Muslim Brotherhood. Clerics declared the economic and military failures of the state to be punishments for aping the West. Men sought to restore order by demanding veiling, harassing women in the streets, and enforcing patriachal dominance.

Islamic revivalism has prevented reform. Bucking a global trend, Muslim-majority countries of the Middle East and North Africa have maintained sexist legislation.

Economic insecurity does not preclude feminist progress

Latin Americans have suffered economic turmoil, yet made massive feminist advances. Female employment, activism, and representation have all soared. Ten Latin American countries now require gender balance among legislative candidates.

Economic downturn in Zambia actually advanced gender equality. Impoverishment forced urban women into the labour market, where they demonstrated equal competence and gained respect.

Culture matters! Since female seclusion was never idealised, Zambian and Latina women could seize new economic and political opportunities.

Male job loss remains dangerous, however. In Brazil, it exacerbates domestic violence. When Copperbelt mines closed and men were retrenched, their wives bore the brunt of ‘icifukushi’ (angry frustration).

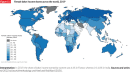

To what extent has relative deprivation worsened hostile sexism worldwide?

Unemployment amongst religious conservatives has fuelled hostile sexism and calls for patriarchal controls. Political elites have gained strength by courting these bigots and restricting women’s rights. We see this in both America and North Africa.

Where else? To what extent does globally uneven progress towards gender equality reflect the underlying economic divergence, men’s frustrations and hostile sexism?

What are the implications of automation? If low-skilled jobs are replaced by robots, men stuck in America’s small towns may become more misogynist. Progress to gender equality may then bifurcate with economic mobility. College-educated men secure high earnings, happily care for their kids and vote for female leaders. Meanwhile, those left behind are lashing out.