Hire Alice Evans

I am on the job market.

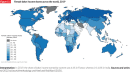

“The Great Gender Divergence” (forthcoming with Princeton University Press) will explain why the entire world has become more gender equal, and why some societies are more gender equal than others.

My analysis is summarised in “Ten Thousand Years of Patriarchy”.

In my view, this is the most fundamental fact about humanity that has not yet been explained. I’m keen to teach brilliant students and expand this new field.

This post outlines my major publications.

Apologies if this email is not relevant for you. Normal service will resume promptly!

Publications

I’ve published in Gender & Society; Socio-Economic Review; Annals of the Association of American Geographers (x2); Health Economics, Policies, & Law; Environment and Urbanisation; Third World Quarterly; Development Policy Review; Development & Change; Gender, Place & Culture; the Journal of Southern African Studies; Gender & Development; Development; Geoforum; the Review of International Political Economy (x2); and World Development.

Paid work in the public sphere promotes gender equality

If people seldom see women undertaking socially valued roles, they tend to presume them less competent and less deserving of status. Such perceptions perpetuate women’s exclusion from prestigious positions.

Exogenous economic shocks that catapult rising female labour force participation increase exposure to women demonstrating their equal competence, and thereby undermine stereotypes. Open discussions are equally important, enabling people to realise wider support for equality.

I published five papers on this theme, including “Women Can Do What Men Can do”, and “For the Elections, We Want Women”. For those who are optimistic about awareness-raising, you might like “Gender Sensitisation in the Zambian Copperbelt”.

Cities can catalyse cultural change

My comparative rural-urban ethnographic research in Cambodia and Zambia examines why cities are catalysts of cultural change.

Costly urban living and greater job opportunities motivate female employment, increase exposure to women in socially valued roles, and provide more associational avenues to collectively contest established practices. Interests, exposure, and association reinforce a snowballing process of social change. As women thrive in traditionally masculine domains, others cease to presume them less intelligent. Women gain status, autonomy, and solidarity through broader friendships. Gathering in the public sphere can be disruptive: critiquing unfairness and emboldening resistance.

Social change is slower in villages. Remoteness seems to limit people’s awareness of alternatives, reinforce gender ideologies, dampen confidence in the possibility of social change, discourage contestation and reproduce gender divisions of labour. However, even in cities, few people are exposed to men sharing care work, as this mostly occurs in private spaces. Accordingly, many men assume such practices are uncommon and anticipate social disapproval.

“How Cities Erode Gender Inequality” focuses on Cambodia, “Cities as Catalysts of Social Change” is on Zambia.

Labour repression in global production networks

I have published four papers on global production networks. These examine the comparative political economy of corporate accountability in Europe, the politics of pro-worker reforms in Vietnam, Asia’s patriarchal trade unions, labour repression in Bangladesh and Vietnam.

In “Export Incentives, Domestic Mobilisation and Labour Reforms”, I propose a complementary relationship between export incentives and domestic mobilisation in improving workers’ rights in global supply chains. Exploiting within-case variation in Bangladesh and Vietnam, I show that the anticipation of economic rewards can motivate governments to reduce labour repression and that domestic activists can then mobilise for substantive reforms.

“Overcoming the Global Despondency Trap” explores why a country might be the first to cooperate in a global prisoners’ dilemma. Theoretically, it proposes a “Despondency Trap”. If reformists never see progressive reforms, they may underestimate wider support and then not invest in sustained mobilisation, which perpetuates a negative feedback loop. But if reformists anticipate domestic support, they may become more optimistic, organise and ultimately secure victory. Drawing on comparative qualitative research across Europe, I examine the drivers of potentially ground-breaking legislation.

Politicising Inequality

“Politicising Inequality: The Power of Ideas” focuses on Latin America.

It argues that inequalities are reinforced when they are taken for granted. But this can be disrupted when marginalised people gain self-esteem, challenge hitherto unquestioned inequalities, and gain confidence in the possibility of social change. Social mobilisation can then catalyse greater government commitment to socially inclusive economic growth – as occurred during Latin America’s commodity boom. This paper contributes to the sociology of inequality by highlighting how ideas matter, differentiating between internalised ideologies and norm perceptions, and detailing the drivers of cultural change.

For a full list of publications, click here.

Teaching. I teach on the political economy of international development. I have written two tiny textbooks.

References: Claudia Goldin, Barbara Risman and Daron Acemoglu

Email: alice.evans@kcl.ac.uk

In my early twenties, overcome by testosterone poisoning, I was an MCP.

In my early 80s, I am a feminazi.

The first country, company, agency, religious organization or other group of people supposedly interested in accomplishing a task, changes their attitude and ceases to sideline over half of the population will Sprint ahead of the competition.

Men's supposed superiority pretty much relied on size, muscle and aggressive behavior.Those days are over. As they used to say in the old west "God created men. Colonel Colt made women equal." JK. Actually, it will be women's capacity for empathy that will Elevate them to leadership positions.