Does it Really Matter if Female Labor Force Participation is Miscounted?

Recently, Surjit Bhalla took me to task for (supposedly) using Female Labor Force Participation (FLFP) as an indicator of women’s status. He argues that FLFP measurement reflects cross-national differences in definitions of work rather than the fundamentals of women’s position in society. Women’s work in home production, for example, is not counted in FLFP. Therefore female labor force participation is underestimated.

In a purely statistical sense, he is right.

Home production is indeed undercounted in FLFP. For example, when West Bengal’s rate of female labour force participation is expanded to include all economic activities that enable households to save expenditure, it rises from 28% to 52%.

But if we’re interested in patriarchy, we must distinguish between different kinds of work. Not every kind of work is emancipatory. Ethnographies, focus groups, and surveys tell us that rural women's contributions are scarcely considered 'work' by men, and sometimes, even by women themselves. Women’s farm-work does not guarantee women's esteem, autonomy or protection from violence. Even if northern Indian women work long days harvesting crops, pounding grain and fetching firewood, they still eat last. As a 19th century Haryana saying goes, "jeore se nara ghisna hai": women as cattle bound, working and enduring all.

We must differentiate between unpaid contributions to the household and ,paid work in the public sphere.

When women work for family-owned enterprises, they remain under the ,control of kin. Market, factory and office employment offer far greater possibilities for female solidarity. Through paid work in the public sphere, women gain esteem, build diverse friendships, discover more egalitarian alternatives, collectively criticise patriarchal privileges, and become emboldened to resist unfairness.

Paid work in the public sphere is counted under ‘FLFP’. So whilst FLFP mismeasurement does erase women’s valuable contributions to their households, it correctly tracks the kinds of work which provide pathways towards female emancipation and solidarity.

Women’s share of paid work in the public sphere varies significantly across the world. This is both a cause and consequence of the global heterogeneity in gender relations.

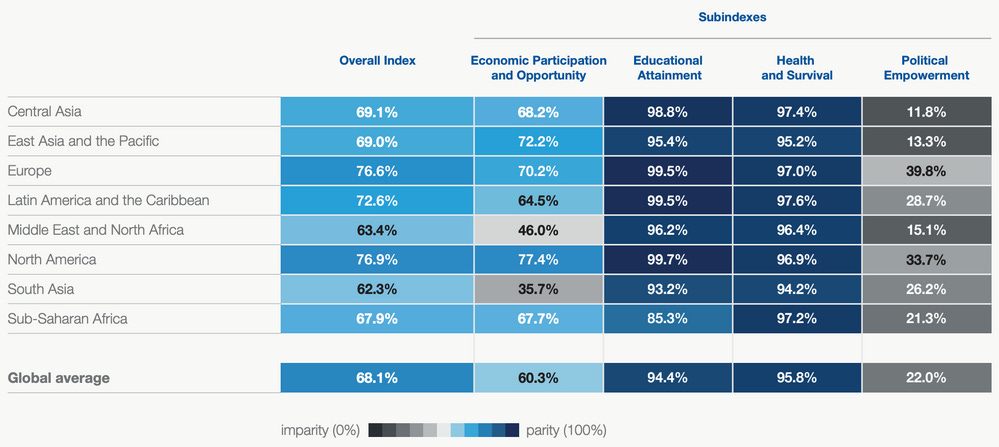

The table below shows how regions differ in terms of “Economic Participation and Opportunity.” This incorporates gender gaps in labor force participation, wages for similar work, earned income, share of senior positions and professionals).

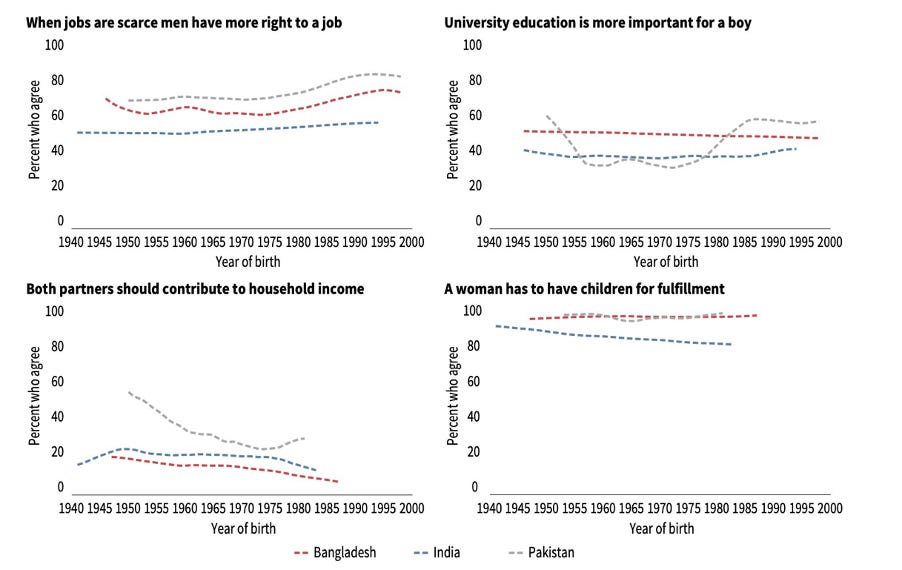

South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa are all caught in what I call “the Patrilineal Trap”. Women’s share of paid work in the public sphere remains low because available earnings are too low to compensate for the loss of male honour. Thus it is men who go out into the world, run family businesses and migrate to new economic opportunities. Women are more typically secluded, steeped in ideals of self-sacrifice, dependent on patriarchal guardians. The few women who encroach on men’s turf are vulnerable to patriarchal backlash: harassment and violence. As home-based South Asian women struggle to forge friendships, they remain beholden to patriarchal ideals.

East Asia was once similarly patriarchal, but job-creating economic growth created the social context in which women could pursue their own emancipation. Daughters gained ‘face’ (respect and social standing) by remitting earnings, supporting their families, and showing filial piety just like sons. By migrating to cities, women made friends, bemoaned unfair practices, and discovered more egalitarian alternatives. Emboldened by peer support, women came to expect and demand better - in dating, domesticity, and industrial relations. Mingling freely in cities, young adults increasingly dated before marriage, chose their own partners, then established their own households. They liberated themselves from parental control. This is a direct consequence of paid work in the public sphere.

Attempts to correctly enumerate women’s home-based work may please statisticians, but tell us little about patriarchy.

Paid work in the public sphere is always counted and heterogeneity in this regard reflects substantive differences in gender relations around the world.

This blog was originally published by Brookings.