Hierarchy and patriarchy are two kinds of status inequality. One mandates respect for authorities, the other concerns men having more status than women. Before now, they have always been considered separately. But this is a serious omission. Both are fundamentally about status: who is owed reverence and deference? Global heterogeneity in hierarchy is a hugely important aspect of “The Great Gender Divergence”.

Some societies are extremely hierarchical. Elders, bosses, clerics and politicians are highly respected. Subordinates keep quiet, use honorific titles, and bow their heads. Other societies are more egalitarian. Dutch Prime Minister Rutte provoked global surprise by cycling to work. But this was perfectly normal for a nation of equals. Swedish bosses similarly act like one of the team.

A hundred years ago, the world was very patriarchal. Men were revered as high status. They were seen as commanding authorities, speaking words of wisdom, capable of better judgement. Women generally had lower status. Although women always made important contributions to family survival, their work was usually devalued.

So what’s the connection between hierarchy and patriarchy? It is my contention that if everyone is equal, it is much more acceptable for women to get to the top. No one is special. ‘Leaders’ are not due unique perks, privileges or power. Queuing by the roadside, they board the bus like commoners. Since everyone is respected, it is much more permissible for (low status) women to become politicians, clerics and bosses. What’s there to envy? The status gap is meagre. The rest of society acts as a reverse dominance coalition - keeping her power, esteem and ego in check.

By contrast, in hierarchical institutions, where status gaps loom large, it would be enormously unsettling for a (low status) woman to command prestige. If men must always bow and let her first speak first, it may grate their egos. Even for men who are perfectly supportive of female employment or gender equality in abstract, it might still be uncomfortable to literally kow-tow. The larger the hierarchy, the more distressing it may be to see a woman soar. Likewise, if the presidency comes with great prestige and is occupied by a black person, racists may get very upset.

My theory helps explain why Scandinavian countries were quick to elect female leaders and share childcare. It also explains why management and politics remain so male-dominated in hierarchical Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Russia and Nigeria.

I am greatly indebted to Erin Meyer’s tremendous book, “The Culture Map”. Her comparative research on corporate practices has inspired me to theorise implications for gender.

Some societies are egalitarian, others are more hierarchical

Danish firms are extremely egalitarian - as Jepsen (a local manager) explained,

“In Denmark, it is understood that the managing director is one of the guys, just two small steps up from the janitor. I worked hard to be the type of leader who is a facilitator among equals rather than a director giving orders from on high. I felt it was important to dress just as casually as every other member of my team, so they didn’t feel I was arrogant or consider myself to be above them. Danes call everyone by their first name and I wouldn’t feel comfortable being called anything but Ulrich. In my staff meetings, the voices of the interns and administrative assistants count as much as mine or any of the directors. This is quite common in Denmark..

Although a lot of Danes would like to change this, we have been bathed since childhood in extreme egalitarian principles: Do not think you are better than others. Do not think you are smarter than others. Do not think you are more important than others. Do not think you are someone special. These and the other Jante rules are a very deep part of the way we live and the way we prefer to be managed” (quoted in Meyer 2014).

Jepsen did not even have an office. Instead he worked in an open space alongside everyone else. This worked well, Jepsen was extremely successful.

However, when Jepsen subsequently relocated to a small town outside Saint Petersburg, he really struggled. He emailed Erin Meyer, with a list of complaints:

“They call me Mr. President.

They defer to my opinions.

They are reluctant to take initiative.

They ask for my constant approval.

They treat me like I am king” (Meyer 2014).

The Russian workers were also dissatisfied, complaining that he was “weak and ineffective”. They wanted someone more dominant.

Moving from a hierarchical to egalitarian society can be equally frustrating. Mexican manager Gomez transferred to the Netherlands, only to be startled by insubordination:

“It is absolutely incredible to manage Dutch people and nothing like my experience leading Mexican teams, because the Dutch do not care at all who is the boss in the room… I struggle with this every day. I will schedule a meeting in order to roll out a new process, and during the meeting my team starts challenging the process, taking the meeting in various unexpected directions, ignoring my process altogether, and paying no attention to the fact that they work for me. Sometimes I just watch them astounded. Where is the respect?”

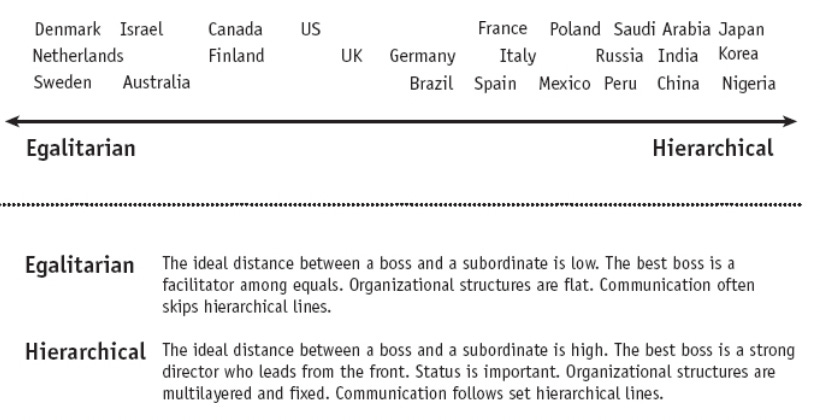

Erin Meyer has helpfully mapped out the global heterogeneity in business hierarchies. She drew on conversations with hundreds of international executives, as well as earlier analysis by Hofstede and the Globe Project. Below, she charts the spectrum of respect owed to corporate authorities.

(This spectrum is consistent with a wealth of data, but it does not draw on nationally representative attitudinal surveys or revealed preferences. As far as I am aware, organisations like Pew, Gallup, World Values Survey and Afrobarometer have not yet not collected data on status hierarchies. There is definitely scope for interested researchers to create representative surveys of hierarchical practices - within smaller firms, religious institutions, and political organisations).

What Caused this Global Heterogeneity in Hierarchy?

Meyer suggests several causes of cross-national variation:

The Vikings were especially egalitarian and consensus-orientated;

The Roman empire institutionalised hierarchy, especially in Italy.

The Protestant Reformation promoted egalitarianism: individuals communicated directly to God (rather than via ecclesiastical hierarchies of priests, bishops and popes).

Confucius extolled hierarchies. Low status persons should obey, while high status groups provided benevolent protection.

These hypotheses are clearly contested! For reasons of space, I will simply note Meyer’s explanations and move on. All that matters for now is that - as a result of thousands of years of cultural evolution - there is a global heterogeneity in hierarchy.

Hierarchies in South Korea and Japan

Drawing on my own interviews, let me share further examples of South Korean and Japanese hierarchies.

Bowing is common - to teachers, company executives and family elders. At Lunar New Year, Korean families bow to their eldest member (큰절). Submission is shown, daily:

“In the work place, it is customary to bow superiors. when passing by CEOs or executives the norm is to perform a “folder greetings” - where one bends at the waist. (Compared to Japanese greetings, it’s less formal though… I guess.) Regarding this greeting culture, “인사“(insa) literally means “the act of welcoming each other with respect.” So basically, in Korea, greeting etiquette seems to be inherently linked with a sense of flattery and appeasement. It is very important. So, I - as a low-ranking individual - would have to 24/7 nunch-ing” (young Korean social enterprise professional, who strongly dislikes ‘nunchi’).

Culture is clearly not static. Younger Koreans are often critical, they want greater voice and autonomy. But corporate practices do seem very persistent, especially in high-paying large firms.

Subordination is also enacted through honorific titles, deferential greetings, managerial oversight, and constant respect for seniority:

“My boss told me to use honorific titles when I write emails: ‘Dear Manager’, ‘Dear Team leader’ etc. there is specific Korean way of calling colleagues based on their position. I was also told that I need to greet my team leader every day when I come. The first thing I do. And preferably I say goodbye before going home. I was also once warned to do these when I forgot to attach titles to messages. When I worked in a ministry, my writing pieces, policy briefs should have gone through our director and approved... One day I wanted to attend a round table as it was my area of expertise, but I was told senior management members would go there” (Uzbek who worked in South Korea).

Respectful titles and social exclusivity set clear demarcations:

“1. Over respect for managers - such as calling them with respectful way (adding 님 addition to their names or adding 님 to a word "사장"(means boss or head). I've observed many people call other counterparts by name directly, but they call the bosses and managers in a respectful manner, even if the manager is young.

2. Smoking with the boss or manager is seen as disrespectful , unless he or she invites you with some gesture. That's why ordinary employees smokes with other employee counterparts while making the circle. Managers (과장) and bosses (사장) make another circle (Uzbek software engineer, working in South Korea)

Visual symbols may accentuate hierarchy:

People wore different coloured lanyards based on their level of seniority… People with the lower status one basically never spoke first in conversations. Bowed heads etc… (European journalist, previously based in Japan).

Where hierarchy is internalised, bad leaders go unchallenged. In 1997, Korean Air Flight 801 crashed. Over 220 people died. After its investigation, the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board criticised the plane’s flight crew (especially the first officer and flight engineer) for not challenging the captain, but instead showing extreme deference.

South Korea now has the same income inequality as the U.K, but far more conspicuous consumption. It is the world leader for spending on luxury goods, male cosmetics, plastic surgery and private education. Koreans are competing for status, because - in a hierarchical society - status is enormously important.

Malaysia gets an even higher score, on Hofstede’s indices for “Power Distance”. As one senior servant explained:

“1. In many corporates (and certainly the government), all workflow follows a chain of hierarchy. The Exec prepares something, which is then reviewed by the Senior Exec, which is then reviewed by the Manager, then the Director, and so on. There's not a lot of autonomy where, say, the Exec can go straight to the Head of the Department.

2. If you go to the offices of SOEs, they will all hang portraits of Malaysia's King, Queen and Prime Minister. The King's portrait is always hung slightly higher than the Queen's, which is then hung slightly higher than the Prime Minister's.

3. Junior employees are usually expected to be silent and to simply take meeting notes, and leave any and all speaking roles (presenting, discussing, etc.) to seniors. And, in the end, the decision is made by the HiPPO (Highest Paid Person's Opinion).

4. Most Malaysian companies have "organisational charts" which display the hierarchy of people in the team. Each department will have an organisational chart and it's always depicted in a "family tree" style with the Head of the department placed at the top of the tree.

5. In Malaysia, there are a lot of honorific titles - Tun, Tan Sri, Dato' Sri, Dato' etc. (the equivalent of Sir, Earl, Baron, Count, etc.). And most of the people who have these titles insist on being addressed by these titles. And people who don't have these titles normally automatically address those with titles by those titles anyway. It would be natural (you don't even have to tell the person to do it) for a non-titled person to call the titled person (e.g. Dato' Sri Azman) as Dato' Sri, instead of Azman, assuming they knew the person is titled.”

Egalitarian Societies and Reverse Dominance Coalitions

Meyer focuses on international firms in the OECD, but there were many egalitarian societies in pre-colonial Sub-Saharan Africa. These provide important insights about the relationship between political egalitarianism and female leadership.

‘Reverse dominance coalitions’ helped maintain egalitarianism within small-scale communities. Foragers mocked, ridiculed, bullied, and berated self-aggrandising ‘upstarts’ who sought to accumulate resources, sarcastically calling them ‘Big Chief’. In the Kalahari, the one influential !Kung San explained,

When a young man kills much meat, he comes to think of himself as a chief or a big man, and he thinks of the rest of us as his servants or inferiors. We can’t accept this. We refuse one who boasts, for someday his pride will make him kill somebody. So we always speak of his meat as worthless. In this way we cool his heart and make him gentle.

If the upstart does not relent, he may be punished with ostracism or even death.

Material conditions buttressed egalitarianism. Sub-Saharan African societies were often ‘heterarchical’: multiple groups vied for influence.

Africans traditionally valued "wealth in people". Land was generally abundant, while labour was scarce. In patrilineal communities, a groom paid the bride wealth and gained control of the children.

African states generally struggled to police their peripheries. The absence of inherited wealth and political centralisation usually constrained any one group from consolidating total control (Rwanda and Ethiopia are obvious exceptions).

African egalitarianism went hand in hand with female leadership, as explained by Nwando Achebe:

In small-scale societies, such as the society of my birth [Igboland], leadership is in the hands of a group of male elders and female elders. Age is so important in these cultures. That's what sets you apart from people who are younger, right? In these small-scale societies, you don't have one king or queen. In fact, they have proverbs that tell you, "if you want to be a king, go be a king in your mother's backyard". That's an Igbo proverb. We don't like kings. And we have another one that says when, "The Igbo have no kings", they don't respect kings. It's leadership in the society and in the group.

So, in societies like that, groups of women come together, in order to lead themselves, in order to support themselves. So instead of having one person in charge, you have groups of women in charge, women coming together to go to the marketplace, women coming together, forming groups to work on this person's farm, because I need help. And then tomorrow I will work on somebody else's farm. Groups of women help each other out.

I suggest that Igboland’s age-based seniority, dual sex systems of governance, and diverse spirituality enabled women to gain status without threatening men’s egos.

TLDR: If everyone is equal, it’s much more acceptable for women to get to the top

In societies where no one is special, men seem much more accepting of female leadership. Whereas in hierarchical cultures, where subordinates must bow to their bosses, female managers and politicians are more strongly disliked. They may even trigger backlash.

This is a novel theory of gender inequality. I believe it helps explain why Russia and Nigeria’s parliaments are almost entirely male, just like Korean and Japanese male-dominated management.

If I’m right, then Scandinavia’s feminist secret is not so much about gender, but rather an evolution of moral and political egalitarianism.

P.s. Thank you to all my friends who helped with this piece!

Further Reading and Podcasts

“The Culture Map” by Erin Meyer

“Female Monarchs and Merchant Queens in Africa”, by Nwando Achebe. Check out our podcast.

“Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior” by Christopher Boehm.

The next step would be figuring out what causes cultures to change their preferred level of hierarchy.

If you've seen a Strindberg play or the Ingmar Bergman film "Cries and Whispers" it seems clear that nineteenth-century Sweden was an extremely formal, class-bound society. Men used to be addressed by their titles ("Engineer Andersson"... although that's a bad example because Andersson is a "common" surname and successful men were sometimes pressured to change their names to something more aristocratic), which is something the rest of us only do for physicians and PhDs. And up until a government-led reform in the 1960s, spoken Swedish had a complex, Japanese-style menu of social registers:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Du-reformen

All of this changed because Swedes consciously decided to become very egalitarian. But why did they do that?

I don't know about this one. First of all I am always very very skeptical of claims in which good things go hand in hand together. But let me state my case.

I know this is a qualitative analysis but there is too much selective analysis and honestly wrong understanding of culture. Following are some of the problem I have:

1.) Jante Law is very much synonymous with a collectivist outlook which in your previous post you considered a detrimental to gender equality. Also Japanese work culture is very much consensus seeking where you can talk to your boss very much freely and has been for a long time. this is not true for how promotion works but there work culture is certainly more open.

2.)Why would Korean's personal consumption be geared towards achieving more status when generally in a collectivist and hierarchical you are not supposed to show off your status: a fact certainly true for Japan.

3.) Now I can argue against the claim that Confucius culture promote hierarchy but my objection here is if I accept the premise about Confucius values being more deferential to hierarchy than why does China(origin of Confucius values) have such a better female representation than SK and Japan in both senior management and in politics despite still having in some sense way worse sexist attitudes.

I have few other objections. But the last point I want to draw attention to isn't any disagreement i have but the simple widely agreed upon point that project of gender equality is a multi generation one and is not as rapid as economic progress in best of circumstances. Hence the secret of Scandinavian success is that due to geographical closeness to UK(birthplace of enlightenment) they just have a early start on countries like SK, Japan. Nigeria, etc.

I am really not trying to be mean or aggressive or dismissive here. Just not agreeing with the analysis.