Did MENA's weak exit options enable religious authoritarianism?

Why do Muslim-majority countries score above the global average for authoritarianism, official protection of religion, religious laws, criminal blasphemy laws, mob attacks on blasphemy, and belief in Hell?

Ahmet Kuru and Jared Rubin point to the long-standing “ulema-state alliance”. Clerics legitimised ruling caliphs, who in turn funded madrasahs, instituted sharia law and empowered favoured clerics.

Faisal Ahmed adds important nuance. He argues that religious authoritarianism was most firmly entrenched in territories conquered by Islamic armies. Political authority was then consolidated under a dictator, with elite slave soldiers, who were compensated with non-hereditary land grants. Absolutist rule was then legitimised by clerics. Authoritarianism persists in places with rents from oil or foreign aid.

But I have one question:

If the Middle East and North Africa was characterised by authoritarianism and religious persecution, why didn’t more people leave? Why didn’t rulers worry about mass exodus?

If people left en masse, then rulers might have been more restrained, for fear that they would lose valuable labourers. Small-scale societies in Sub-Saharan Africa were relatively egalitarian because reverse dominance coalitions contested elites, while maintaining credible threats of exit. Why didn’t this happen in MENA?

Until now, this question has not been answered. No one has provided a globally comparative analysis.

Before I share my theory, here are some useful maps, showing the global distribution of blasphemy crimes, countries with official state religions, belief in Hell, and importance of religion.

Let me offer a hypothesis:

Weak exit options enabled religious authoritarianism.

Circumscribed regions (with weak exit options) were early sites of cooperation, coercion and state formation.

Military and writing technology enabled rulers of circumscribed regions to capture and tax larger territories. This amplified authoritarianism.

Authoritarianism was more likely in circumscribed areas with awful exit options.

Islamic armies captured territories that were circumscribed.

Islamic rulers claimed divine legitimacy, banned apostasy and persecuted minorities.

Circumscription deterred escape and thereby enabled religious persecution.

Religious homogenisation was then collectively enforced.

(1) Circumscribed regions were early sites of cooperation, coercion and state formation

Back in 1970, Robert Carneiro proposed ‘circumscription theory’. Groups battled for control over circumscribed scarce arable lands, then losers were compelled to submit because the ecological alternatives were too bleak.

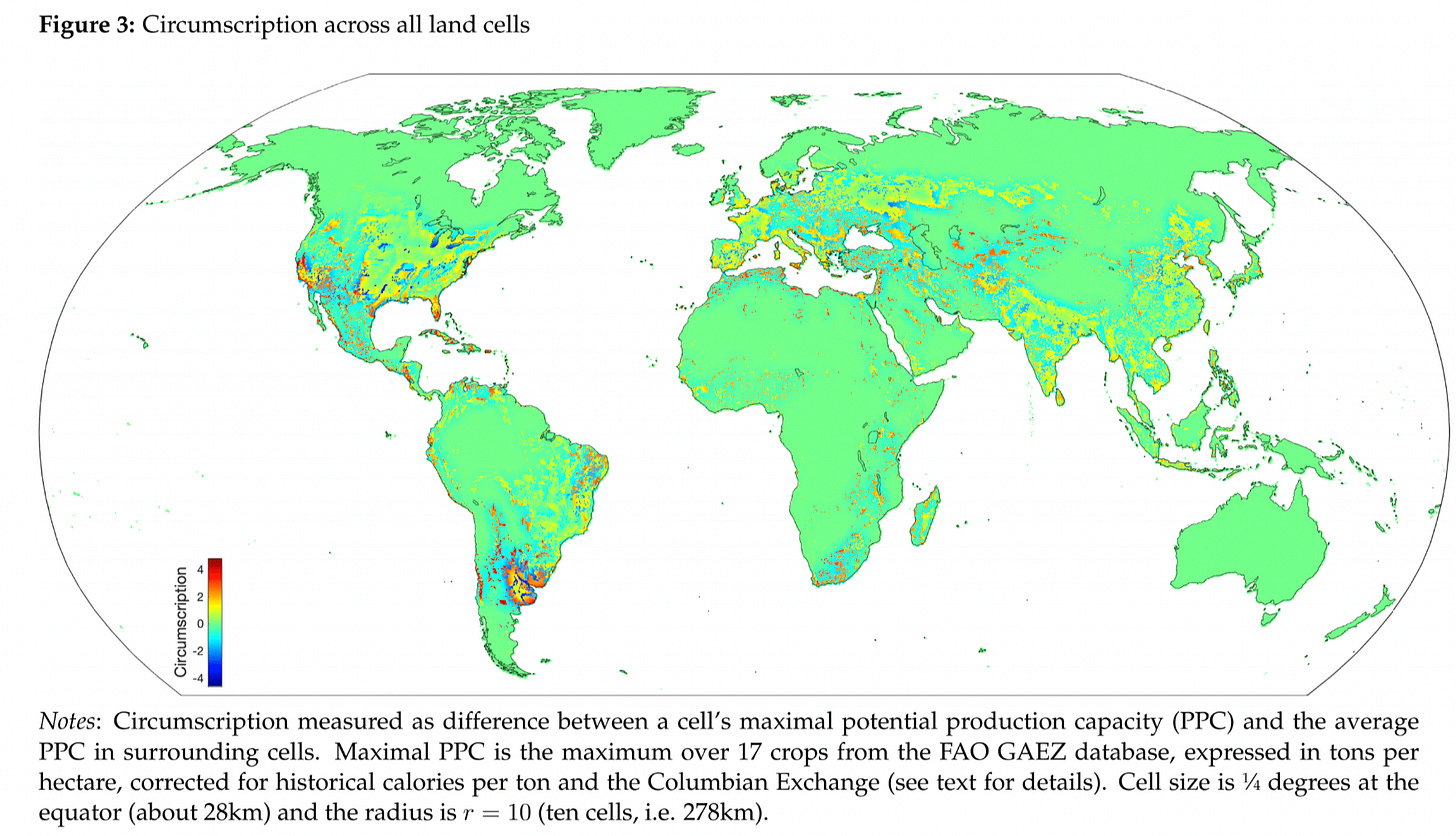

Circumscription’ is calculated by computing the difference between the productivity in a cell and the average productivity of all surrounding cells. Across the American Midwest and Western Eurasian steppes, pre-state agricultural productivity is pretty similar, so ‘circumscription’ is low. In the fertile Nile valley, by contrast, circumscription is high.

Schönholzer and François (2023) harness Seshat data to show this empirically: circumscribed regions were early sites of cooperation, coercion and state-formation.

The “Fertile Crescent”, North African coastline, Mesopotamia, Central Asian oases and Ferghana Valley are all highly circumscribed (as shown in red).

Southern Mesopotamia, Susiana, Konya Plain, Kachi Plain and Sogdiana all saw early state formation (as shown below by Schönholzer and François).

Circumscription did not, however, entail stratification or authoritarianism

Indus cities (c. 2600–1900 BC) had sophisticated technologies (like writing), but little evidence of stratification. There is no evidence of palaces.

Nor is there any evidence of palaces in early Ashur. Hereditary ‘princes’ were not even permitted to call themselves ‘kings’. The ruling dynasty governed in collaboration with male citizens.

What changed?

(2) Military and writing technology enabled rulers of circumscribed regions to capture and tax larger territories. This amplified authoritarianism.

Improved military technology (like chariots) enabled imperial expansion (Turchin et al 2022).

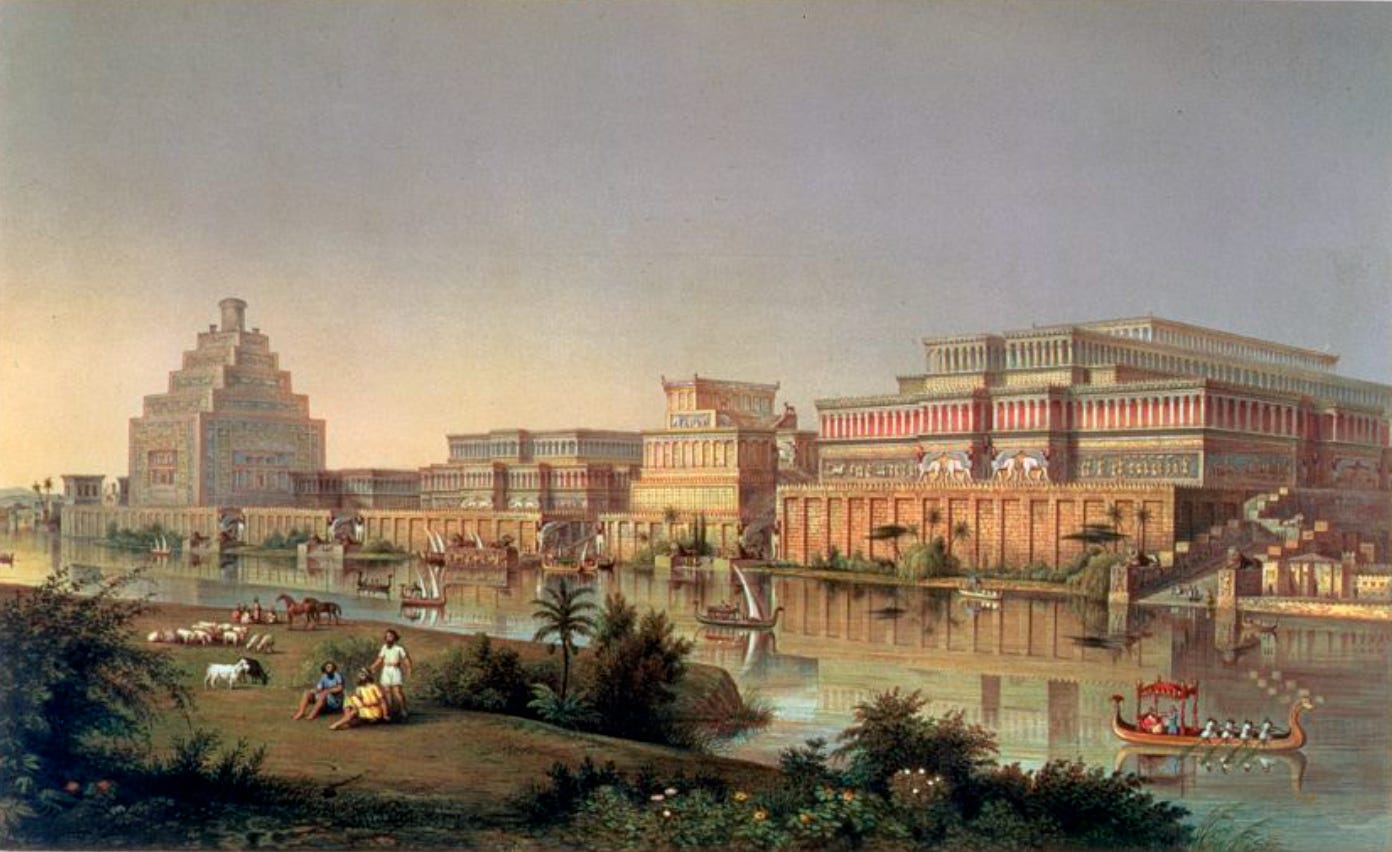

In Assyria, powerful kings marshalled professional armies, conquered vast territories, presided over complex bureaucracies, and conscripted thousands of workers. The City Assembly was replaced by a royal court. Assyrian monarchs proclaimed themselves “king of the world.”

Globally comparative, longitudinal Seshat data thus points to an interaction between circumscription and technology. Early states developed in circumscribed regions. Rulers then consolidated wealth and power via military might.

Authoritarianism was further amplified by irrigation, canals and writing technology. David Stasavage argues that rulers wanted to tax at the right level. If rulers could accurately predict crop yields, they could tax at a level that maximised revenue, without starving the peasantry. Ruling elites harnessed writing technology in order to accurately predict yields without ceding any power.

(3) Authoritarianism was more likely in circumscribed areas with awful exit options

Chariot warfare and writing technologies enabled rulers to conquer and tax larger territories, accumulate more wealth, and centralise political authority. Subjugated masses remained, since their exit options were even worse.

(4) Islamic armies captured territories that were circumscribed and predisposed to authoritarianism

Between the 7th and 9th centuries, Islamic armies conquered territories east and west.

This may be because they followed existing trade routes, camels were suited to deserts, and Islamic redistribution appealed in regions with high inequality.

(5) Islamic rulers claimed divine legitimacy and banned apostasy

In the Ridda wars of the 7th century, contending Arab leaders battled for authority. All claimed righteous lineage.

In terms of jurisprudence, the first four centuries of Islam were relatively open. There was broad tolerance of independent reasoning (itjihad).

From the 10th century, the gates of itjihad were closed. As Jared Rubin explains, jurists were thereafter supposed to accept previously codified wisdom. So began what Ahmet Kuru calls “the ulema-state alliance”. Clerics praised the caliphs in their Friday sermons, encouraged obedience, and accompanied them on pilgrimages. In return caliphs institutionalised sharia law, while entrenching favoured clerics.

In his new book, “Freedoms Delayed”, Timur Kuran sees bans on apostasy as a core aspect of Islamic history. (‘Apostasy’ means leaving one’s religion). Kuran gives many examples of Middle Eastern clerics and leaders who violently quashed dissent, persecuted various sects, and forced religious homogenisation.

Both Ahmet Kuru and Timur Kuran emphasise the influence of Ghazali.

‘Ghazali helped to establish the practice of treating heterodox Muslims as apostates who deserve execution. He urged the killing of independent philosophers as well as Ismaili Shiis, insisting that rulers and their military had a duty to destroy heretics… The fatwas of leading Islamic interpreters, such as Ghazali… were collected in volumes for use by later interpreters… statesmen and judges’.

This raises one hitherto unanswered question:

Why didn’t more people leave?

(6) Circumscription deterred escape and thereby enabled religious homogenisation

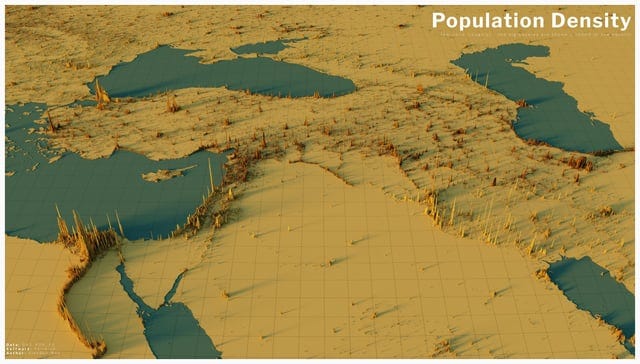

The Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia’s densely populated regions were highly circumscribed (as shown below). Peasants had terrible exit options. Very few people wanted to live in the desert or mountains. So they stayed put.

But those who stayed faced violent authoritarianism. Apostasy (leaving one’s religion) was punished with execution. The Almohads zealously persecuted religious minorities. Memory of bloodshed encouraged religious conversion and conformity.

While Faisal Ahmed suggests that Islamic armies instituted mamluk institutions, perhaps they were only successful because conquered people had no where else to go.

Some groups did escape to remote rugged regions and remained culturally isolated. The Kalash in Pakistan’s north-western valleys are polytheistic. Amazigh nomadic pastoralists also escaped Almohad persecution by retreating to the Atlas mountains. But those who remained on the plains tended to assimilate.

Population density remains highest along the Fertile Crescent.

Central Asia provides a good comparison.

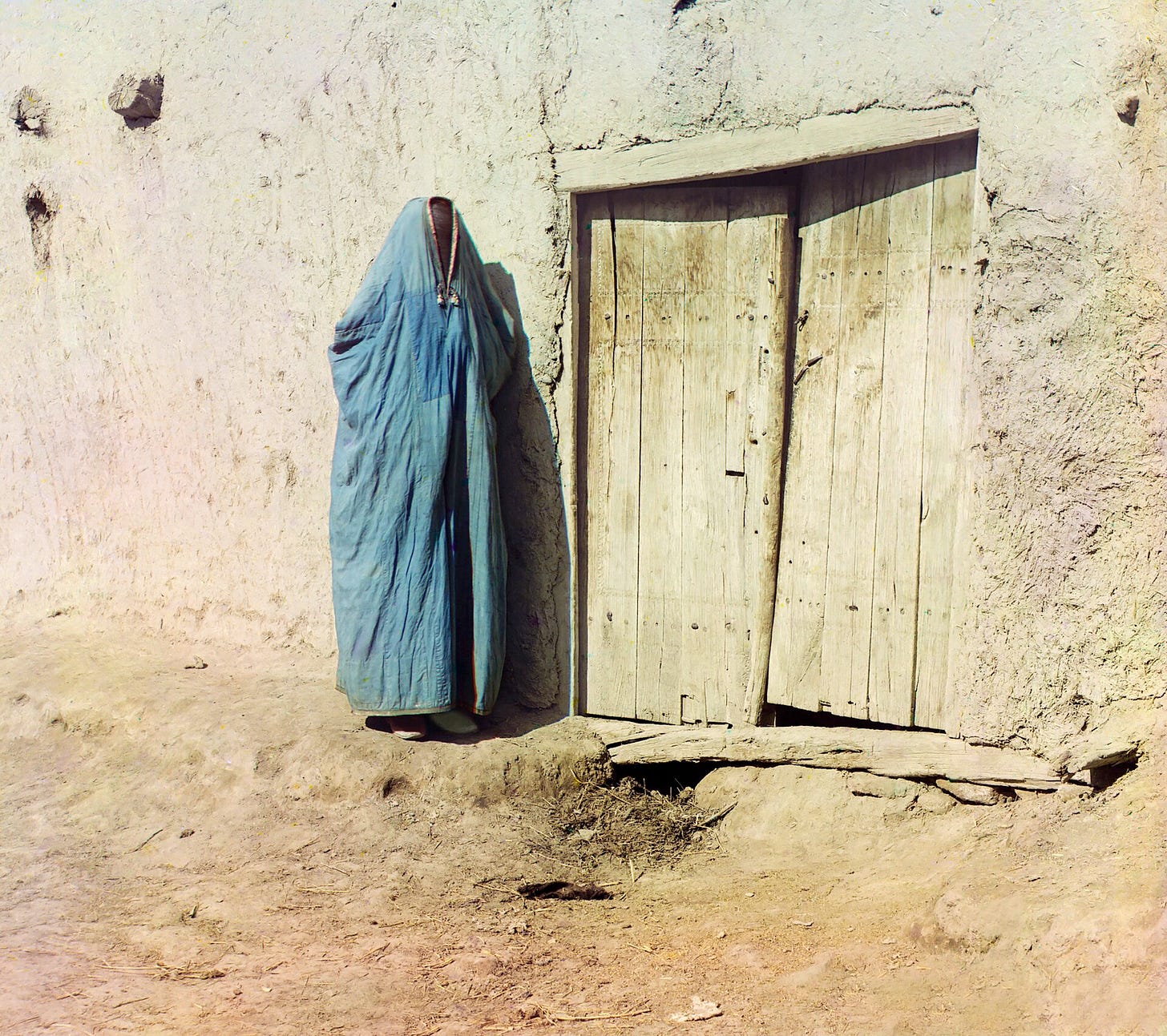

Fergana Valley was highly circumscribed: rich arable land is wedged between the Tein Shan and Pamir Mountains. After Islamic conquests, there was gradual cultural, religious and linguistic assimilation. Central Asia’s jurists, mathematicians, astronomers, scientists and geographers in the 9th-11th centuries all wrote in Arabic. Poetry and high culture was largely Persian. As part of cultural assimilation, they also adopted tribes and cousin marriage. Urban Uzbek women wore paranjas; they idealised female seclusion.

The Steppe, by contrast, has zero circumscription. Nomadic pastoralists defied control or coercion. Kazakhs thus maintained their customs. They remained patrilineal exogamous (never adopting Arab cousin marriage), only adopted Islam superficially, continued to drink alcohol, practise Shamanism, worship fire, worship ancestors, sacrifice horses, and represent animals in their burials.

Zero circumscription enabled the persistence of Turkic culture.

(7) Religious homogenisation fosters cultural tightness

Once religious homogeneity is widespread, it is not necessarily enforced by rulers or clerics, but collective enforcement. This includes

Credible cues of widespread religosity

Festivals, fostering joy and community;

Suppression of dissent

Cultural tightness and

Inter-generational socialisation.

Fasting for Ramadan can be tough. Seeing this widespread sacrifice, onlookers may infer that everyone is deeply committed, which in turn encourages religosity.

Festivals (like Eid) also bring people together; generating warm, fuzzy feelings of love and community. Longer Ramadan fasting boosts happiness!

Homogeneity may also be instilled through violence. Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Indonesia and Jordan have the highest number of mob attacks on blasphemy. In August this year, a crowd in Lahore attacked a factory owned by an Ahmadi and accused him of blasphemy. Rather than punish the attackers, Pakistani police charged eight Ahmadis with blasphemy.

Even if one is privately sceptical, one may nevertheless want to appear devout so as to secure wider public approval. Publicly performing piety enhances one’s reputation as good, trusted and respectable.

Together, this likely encouraged what Michele Gelfand calls ‘cultural tightness’. In societies with mass conformity, hegemonic practices tend to be revered as normative. Deviation is punished. Seeing that condemnation, others self-police. This feeds a negative feedback loop, suppressing dissent.

Parents also teach their children how to behave correctly, so they will be widely respected and marriageable. If young men’s honour is contingent on their sisters' chastity, they may impose tight restrictions.

TLDR: weak exit options enabled religious authoritarianism

The established scholarly consensus is that there has been a millennium of religious authoritarianism in the Middle East and North Africa. Dissent was suppressed by the “ulema-state alliance”.

But this leaves big, unanswered questions:

Why didn’t more people leave?

Why didn’t leaders worry that repression would cause mass exodus?

Here’s my hypothesis. MENA scores highly for circumscription. Exit options were terrible. Rather than venture into the desert or mountains, most people stayed and conformed under religious authoritarianism. Repression encouraged homogenisation. After Sunni Islam reached critical mass, it has been collectively enforced through cultural tightness.

Isn't your notion of circumscribed regions put far more succinctly by Karl Wittfogel with his concept of "hydraulic despotism": a tyranny which rules thru control of the water supply?