Did Forced Resettlement promote Cultural Tolerance and Assimilation?

Kazakhstan is an under-rated beacon of secular tolerance. Only 29% say religion is very important. Just 10% favour Sharia law, and only 4% think those who leave Islam should be punished. These are some of the lowest scores in the Muslim world.

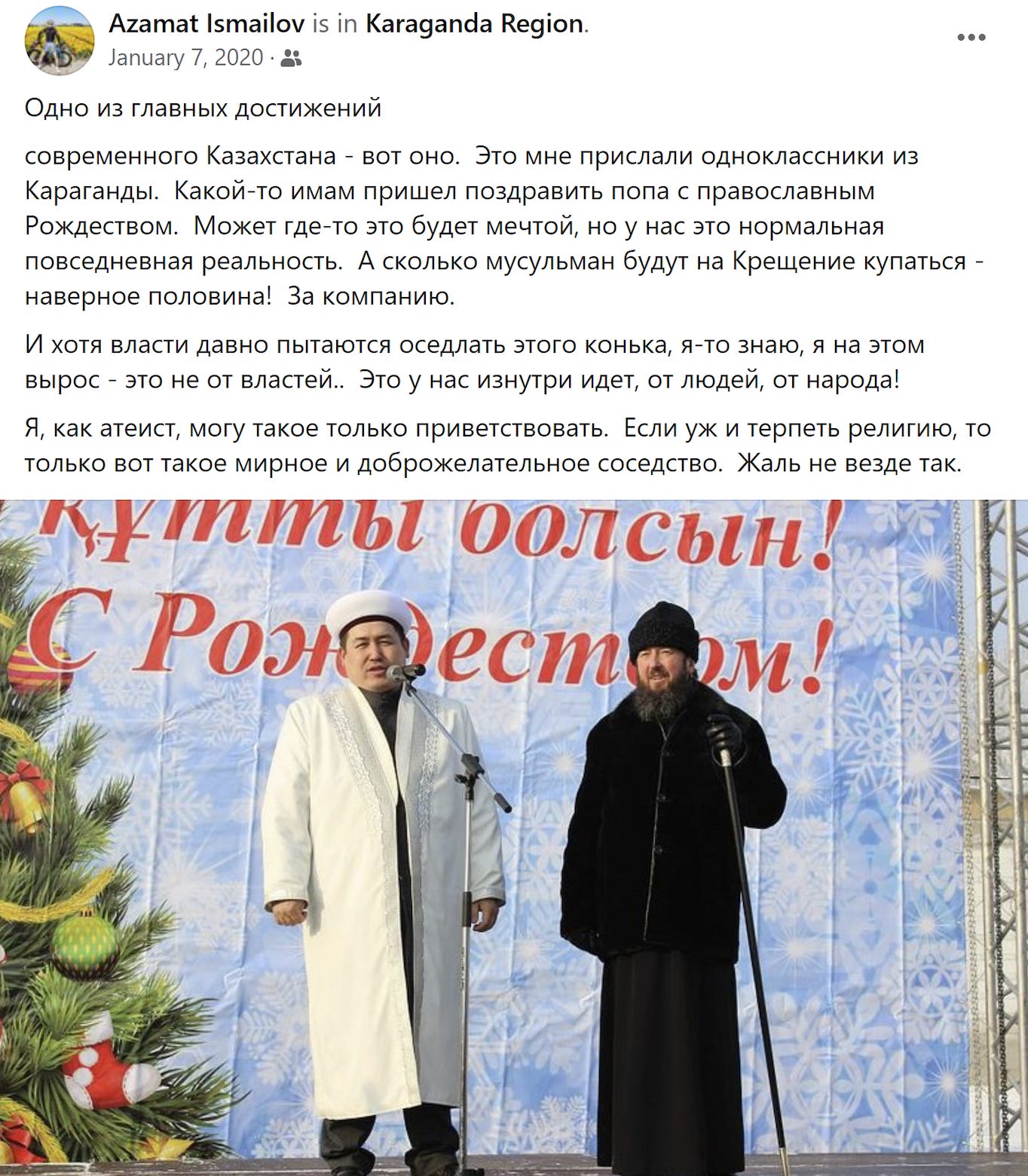

This screenshot shows a Muslim and an Orthodox leader jointly celebrating Christmas in a country that is majority Muslim, while Azamat Islmailov outs himself as an atheist.

How did this happen?

Nomadic pastoralists only adopted Islam superficially

Roaming across the vast Steppe, nomadic pastoralists were rarely schooled by Islamic madrasas nor governed by Sharia courts. Kazakhs and Kyrgyz maimed Turkic culture. They continued to drink alcohol, practise Shamanism, worship fire, worship ancestors, sacrifice horses, and represent animals in their burials.

Turkic mythology, sagas, skeletons and inscriptions suggest that women actively participated in public life. Kazakh girls were encouraged to develop their capabilities and compete with men - in music, poetry, and sometimes horse racing.

So even before the USSR, nomadic commitment to Islam was pretty weak.

But pre-Soviet variation cannot be the whole story. Like Kazakhs, Krygyz were also nomadic pastoralists. Yet today they are doubly religious and three times more likely to favour Sharia. Why might this be?

Economics?

Kyrgyzstan is still very poor. Poorer people tend to be more religious. There are several possible hypotheses - which may hold to differing degrees for different people.

Religious communities provide valuable club goods. Economically hard hit communities in Brazil turned to Pentecostalism. Public piety secures inclusion.

Rituals foster group-bonding and community;

Precarious communities survive through mutual insurance and inter-marriage. Veiling and other markers of piety signal that you’re a ‘good person’.

Economic desperation may make people long for a close connection with the divine. If everything else is failing, religious identity may provide righteous purpose. When life is harsh, heaven becomes incredibly appealing. If you are pious, you can reach eternal paradise.

But let me suggest three reasons for doubt:

It doesn’t explain why many high-earners in wealthy countries are very devout.

Even at similar levels of income, there’s still a lot of variation. Malaysian Muslims are three times more likely than Indonesians to favour the death penalty for leaving Islam.

The instrumentalist explanation that people only signal piety to secure club goods doesn’t seem to capture fervent religosity or violent punishment for blashemy. Saying someone should be stoned to death for leaving Islam is a lot more extreme.

Forced resettlement and multiculturalism

Under the USSR, Kazakhstan was heavily Russified. There was also a major inflow of Germans, Chechens, Koreans, and Ukrainians - usually by force.

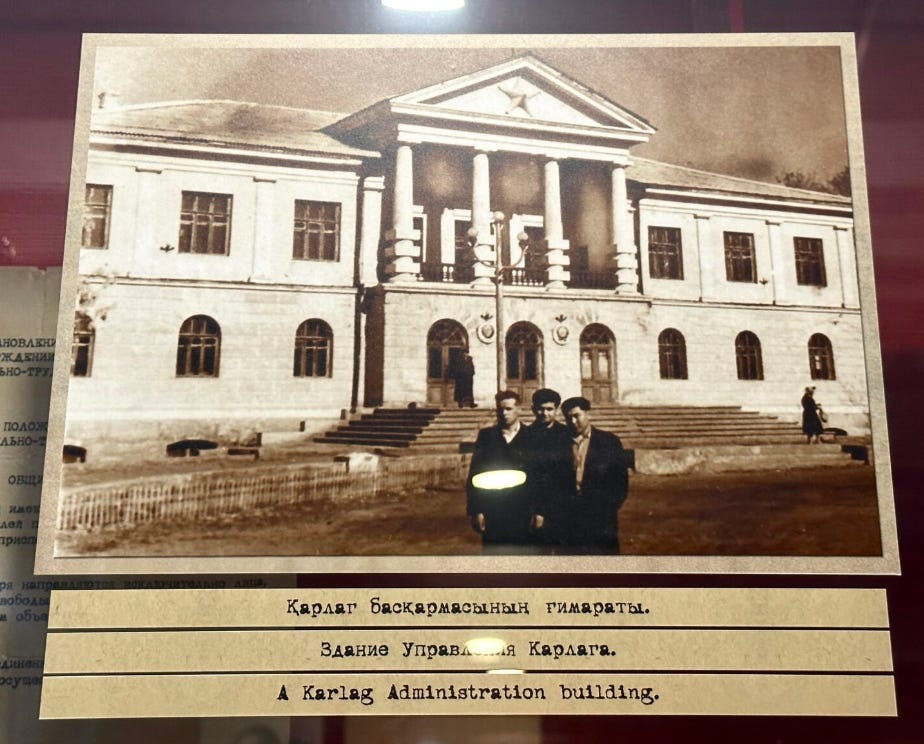

Between 1931 and 1959, a million ‘enemies of the people’ (vragi naroda) were sent to the Karaganda Corrective Labor Camp. ‘KarLag’ was 300,000 square miles - the size of France. By 1959, Kazakhs were outnumbered by Russians.

Economists Gerhard Toews and Pierre-Louis Vezina show that ‘enemies’ were typically highly educated. Intellectuals, scientists, politicians, businessmen and artists were deemed a threat and forcibly resettled in labour camps. Descendents of vragi naroda are now more educated and their surrounding areas are more developed.

But what was the impact on culture?

Forced resettlement and multiculturalism

I interviewed a young woman whose family came from Karaganda (near the gulag). She shared her family story of famine, repression, and multiculturalism.

“My great-grandmother survived the 1930s famine. It was horrendous. 6 of her 7 children died. Most of my relatives don’t speak about it.. If you ask my grandmother, one day she’ll say it’s okay we had a nice life, another she’ll say Stalin deserved to be beheaded in the square… My parents describe growing up as a dystopian nightmare.

They grew up in Karaganda, close to the gulag. Political prisoners from the USSR were sent there. Gulag prisoners were released in 1954 but they had to stay in Karaganda… Almost everyone at their school was Russian, German or Korean. There’s a huge Korean theatre. Shops sell Korean food, it’s extremely multicultural.

There are two gay clubs in Almaty, there’s more freedom to do anything. And there’s strong religious tolerance. Muslim and Orthodox leaders celebrated Easter together in Karaganda... For us, this is normal. It is not from the state, it comes from the people”.

My grandmother would hold up a shot of vodka and say - without irony - ‘Happy Eid!’. She was a paramedic, my grandfather was a surgeon. They met on the job. My family is full of working women, who’ve used opportunities to advance themselves… If there was an opportunity, they took it… Compared to Uzbeks and Tajiks, women had more mobility and flexibility”.

Makhabbat also introduced me to the popular Kazakh boy band “Ninety-One”. Modelled on Korean boy bands, these men celebrate individual freedom (a discourse I seldom heard in Uzbekistan).

Holy Assumption Cathedral Church

Political prisoners were also sent to Uzbekistan. The NKVD deported tens of thousands of Russian Germans, Karachays, Balkars, Chechens, Kalmyks, Ingush, Crimean Tatars, and Meskhetian Turks to work on cotton plantations. In 1944, over 150,000 Crimean Tatars were deported to Uzbekistan.

In conservative Namangan, most women are heavily veiled and stay away from men. Here I interviewed a Crimean Tatar waitress - sporting a short wool dress, leggings and bright red lipstick. She is certainly unusual, but the presence of women like her may still be contributing to more open-minded tolerance.

In this society, women are not allowed to use perfume, because if a stranger smells her it will be considered a sin of a relationship.. Uzbek men often tell me to dress more decently and wear baggier clothes. But I tell them that it’s my choice, I do what’s comfortable for me.. Now they’ve become more accustomed to me. [translated]

In Sang village, I interviewed an elderly Uzbek teacher. She had started wearing short-sleeved dresses like her Russian colleagues. One of her friends - a 66 year old former accountant - similarly recalled her enjoyment of socialising at work:

Jews, Germans, Tatars, and people from many nationalities all shared lunch, each bringing their national dish.

My qualitative research with Uzbeks and Kazakhs is consistent with a much larger body of evidence. When people collaborate towards shared goals, while performing roles with similar status, they come to see each other as equals, and become more open-minded. Communism may have been important, in suppressing inter-group inequalities, thereby suppressing status hierarchies.

Cultural assimilation, by force

None of this is to suggest that Kazakhstan is a feminist utopia (one government minister recently beat his wife to death). Nor is it a defence of gulags. As a social scientist, I’m just trying to understand cultural diversity.

So now let’s contrast two major actions of the USSR:

The Soviets tried to crush Islam by force. But coercion did not stamp out underlying desire. Uzbeks just falsified their preferences and privately prayed at home. Now that persecution has rescinded, Uzbeks are publicly expressing religiosity. Mosques are being constructed, streets are blocked for Friday prayer, religious vloggers attract hundreds of thousands of subscribers, and women are veiling.

But the Soviets may have nevertheless been unintentionally effective in promoting a genuine preference for secularism. Forced resettlement of dissidents may have enabled multi-cultural mixing and inter-faith tolerance.

There are two possible effects on gender. First, as Kazakhs embrace atheism, they may disavow religious tenets (e.g. that women should stay away from men). Second, by interacting with Russians, Jews and Germans, they may have culturally assimilated.

Forced resettlement may thus help explain why Kazakhs are now far less religious, far less likely to favour stoning as punishment for leaving Islam, and far more likely to support gender equality.