Culture and jobs in Asia

Female employment in India is extremely low. Men’s honour depends on female chastity. Given weak job growth, female earnings are very paltry and thus provide insufficient compensation. Families would rather maintain their prestige and place in vital networks than gain a handful of rupees. Female employment will only rise when earnings are sufficiently high to compensate for men’s loss of honour.

Some other scholars think I’m wrong. They think it’s purely a function of low demand. Employers typically prefer men (typing them as more reliable and productive). So when crowds of men surge for scant opportunities in railways or other government posts, women are left at the back of the queue.

That’s partly true. Mechanisation has lowered demand in agriculture, leading rural female employment to plummet. Neither industry nor services have been sufficiently labour-hungry to absorb surplus labour. Jobs are scarce.

Culture is also hugely important. This mediates families’ willingness to send their daughters to school and let them seize economic opportunities. Where male honour is primary and depends on female seclusion, women stay at home.

Let me illustrate via a comparison with China. It was historically patrilineal, just like India. Since descent was traced down the male line, great care was taken to remove suspicions of female promiscuity. Unmarried women were thus surveilled. Sons, meanwhile, were revered as scions of the family line, provided for ageing parents, and performed ancestral rituals.

But Chinese families had a stronger preference to exploit female labour. This small difference in culture mediated families’ responses to economic opportunities.

Back in 1990, the two countries had similar GDP per capita (see graph below).

But even in 1990, the gender gap in education was far smaller in China. Families were far more willing to fund their daughters’ education and permit them to travel.

India’s gender gap was much larger, but has now closed. Rising male education builds demand for female education, as grooms want educated wives to school their children.

The graph below comes from a new NBER paper by Barbara Fraumeni.

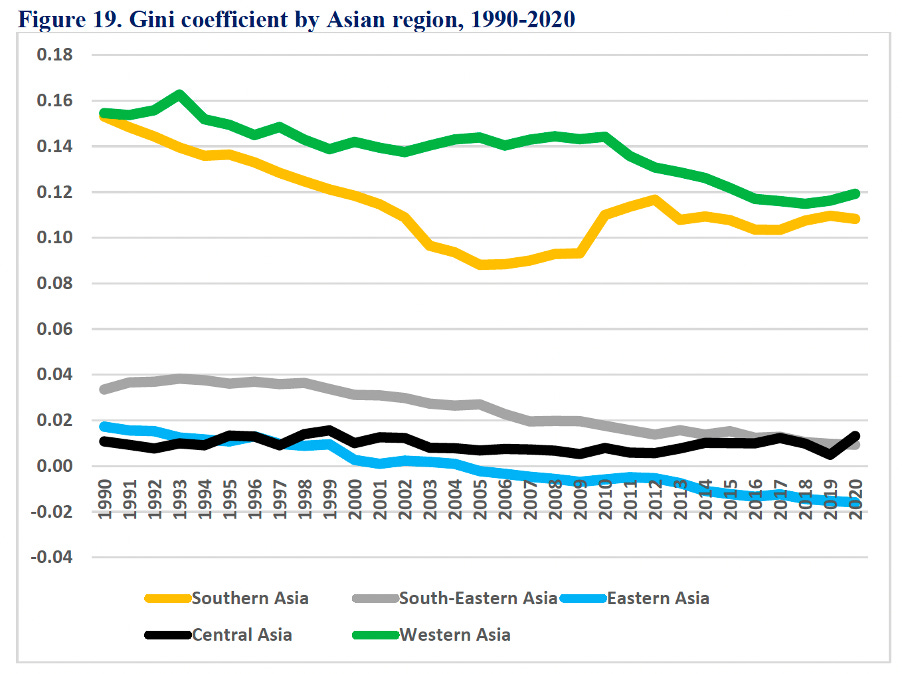

India is not alone. More patriarchal regions typically have larger gender gaps. Contrast patrilineal Western Asia and bilateral/ matrilineal South-eastern Asia (where there is parity).

Fraumeni also constructs a ‘Gini gender coefficient’, which is the ‘gender distribution of human capital among educated people’. This Gini is clearly much larger in more patriarchal cultures.

This same pattern holds for employment. When China was just as poor as India, in 1900, the gender gap in youth employment was zero. Even though available earnings were fairly meagre, Chinese families were much more willing for their wives and daughters to work.

Now you may object that GDP per capita is not a perfect proxy for economic opportunities, since China had a large share of state-owned enterprise. Fair.

But the trends holds more broadly, irrespective of state-owned enterprises. Patrilineal Western Asia’s gender gap in youth employment is large. Southeast Asia’s is small.

Culture clearly mediates the rate at which women seize economic opportunities.

So thank you to Barbara Fraumeni for very nice descriptive data! 😊

Could you explain a little more about how the Gini gender coefficient is constructed?