Can Laws undo Sexism?

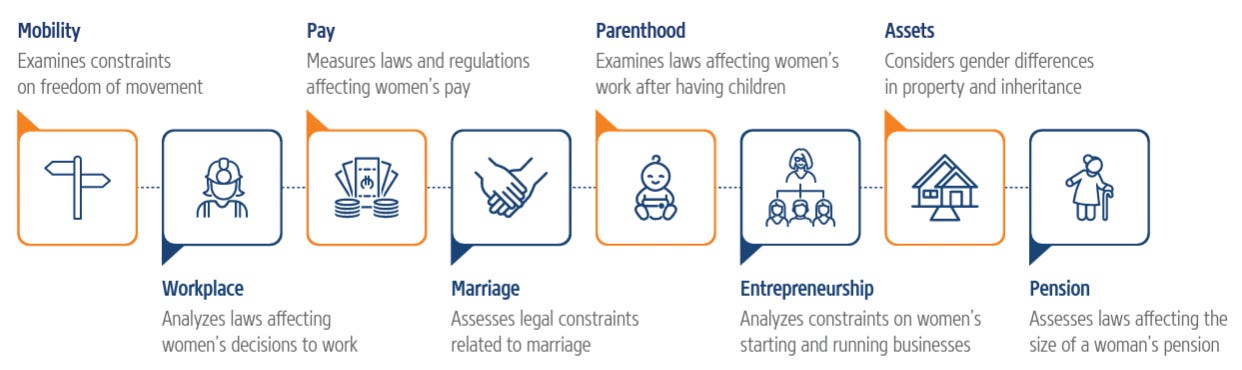

2.4 billion women still lack men’s legal rights. Legal discrimination persists in most countries: regarding mobility, employment, entrepreneurship, assets and pensions. The World Bank is pushing for parity. This begs the question,

Can laws undo sexism?

This Substack discusses:

Descriptive data on legal discrimination;

Government effectiveness

Men’s honour and reliance on kinship

Female seclusion inhibits claims-making

Despondency traps

Risks of incentivising legal reform.

1) Descriptive data on legal discrimination

Only 14 countries have full legal equality in all domains. European countries score highly for parity, while the Middle East and North Africa have many sexist laws (especially on mobility).

2) Government effectiveness

Even if sexism is legally proscribed, it may not be legally enforced. As Zambian parliamentarians repeatedly insisted, ‘the problem is implementation’.

In Liberia, women’s movements have pushed for enforcement, but this remains paltry in remote rural areas. Rwanda’s majority-female parliament has passed an inheritance bill, but women still struggle to secure these rights.

Why is implementation so hard?

Weak state capacity

Uganda has just revised its inheritance law to protect widows. But how can she possibly claim this right? Remote villages may be several hours drive from the nearest police post, or longer if waterlogged. If victims cannot get help, abuse continues with impunity.

Communications are also limited. Extremely poor families cannot afford radios, let alone smartphones. Remoteness forestalls exposure to critical discourses, networking, and contentious claims-making. In rural Zambia, neighbours may privately condemn assault but hesitate to intervene because they anticipate community disapproval.

Less than 20% of Sub-Saharan Africans live in urban agglomerations of more than one million. That’s a major challenge for law enforcement and government effectiveness.

Informality

The vast majority of Africans and Asians remain trapped in informality.

79% in India

75% in Indonesia

87% in Mozambique

They are employed in micro-enterprises, ranging from one-man entrepreneurial operations to petty family firms with a handful of workers. Such work is precarious. Small-scale self-employment is without job security or regular pay cheque, let alone insurance against unemployment and workplace injury. Those seeking jobs in micro-enterprises must get lucky at the labour chowk just to be hired for the day. Or they may be rounded up by harsh, exploitative middlemen. The fortunate ones might work for a prosperous uncle.

The World Bank notes that 93 economies still do not mandate equal remuneration for work of equal value, but against who might this right be claimed?

Without contract-enforcement, rules against discrimination verge on irrelevance.

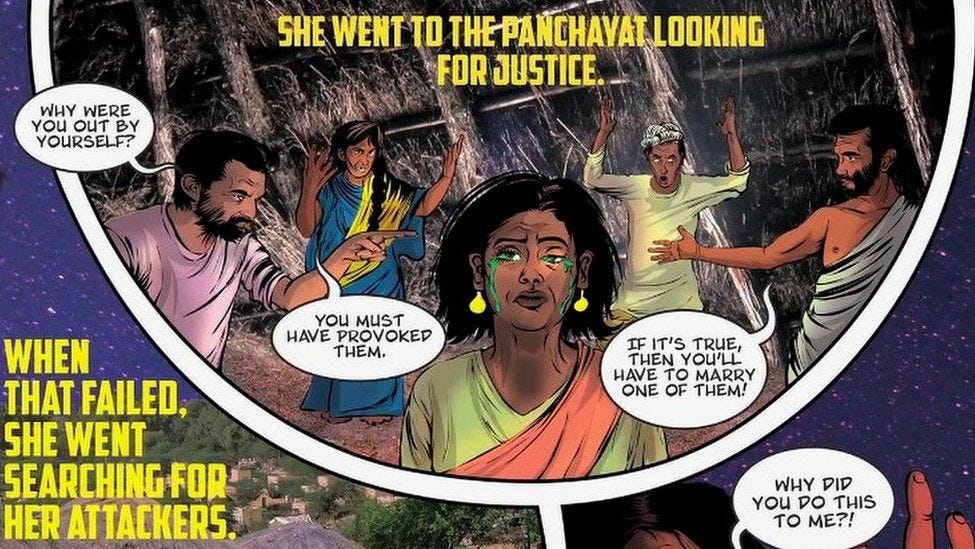

Incapacitated criminal justice systems

India is a great example. Unlike much of the Middle East and North Africa, it provides a range of legal protections against acid attacks, dowry domestic violence, divorce, and inheritance. Indian women’s legal rights do exist on paper.

But are they claimed and enforced?

Barely.

Only 4% of Indian women have actually inherited land!

The criminal justice system is incapacitated. India has one of the lowest police to civilian ratios in the world: one officer for every 720 people. Police stations are poorly equipped. As of 2018, 28.5 million cases were pending in India’s district courts.

Of all cases tried under 498A (Indian criminal law against domestic violence) only 16% result in conviction. 31% of cases await police investigation, 90% await trial. In Punjab the conviction rate for violence against women is less than 3% of registered cases.

As Poulami Roychowdury details in her fantastic new book, “Capable Women, Incapable States”, Indian police are short-staffed and over-burdened. Despite legal entitlements, the state is no ally. Officials in West Bengals’ criminal justice system routinely refuse to help, fail to process documents, lose evidence. Victims are dismissed. Cases languish.

Payel ran away from her abusive husband and wanted to retrieve her dowry. Visiting the police, her face was visibly wounded from where he’d scorched her with a hot spatula. But the police were too busy.

Law enforcement officials typically blame the victim and disrespect marginalised women. Dalits and Muslims believe that the criminal justice system views them with disdain and disrespect.

‘The police officers didn’t help at all. The police pushed me to drop the case and to say that he didn’t do it. Whatever I said the police refused to write down’ – explained an acid-attack victim in Bangladesh. Courts, police, doctors, and nurses are unsympathetic to victims of gender-based violence. Victims of acid-attacks are isolated and stigmatised, pressured to marry their assailants. Indeed, survivors are nearly always encouraged to reconcile with their abusers.

3) Men’s honour and reliance on kinship

Given the dearth of good jobs and state protection, Arabs, Persians, Uzbeks and Indians remain heavily dependent on kin. Social connections are necessary to access jobs, secure permits, avoid trickery, and resolve conflicts. Even middle-class, professional Jordanians acquire social insurance from kin. Ever at risk of ruinous monsoons or health shocks, Indian jatis provide vital insurance.

If inclusion is contingent on male honour and female seclusion, then women remain close to the home. Employment laws are almost irrelevant.

Even if labour laws forbid women from working at night or in male-majority sectors like mining and railways, what family would forfeit their honour and risk alienation?

Even if laws on male guardianship are over-turned, family life may remain the same. Sharia law remains widely supported in many parts of the Muslim world.

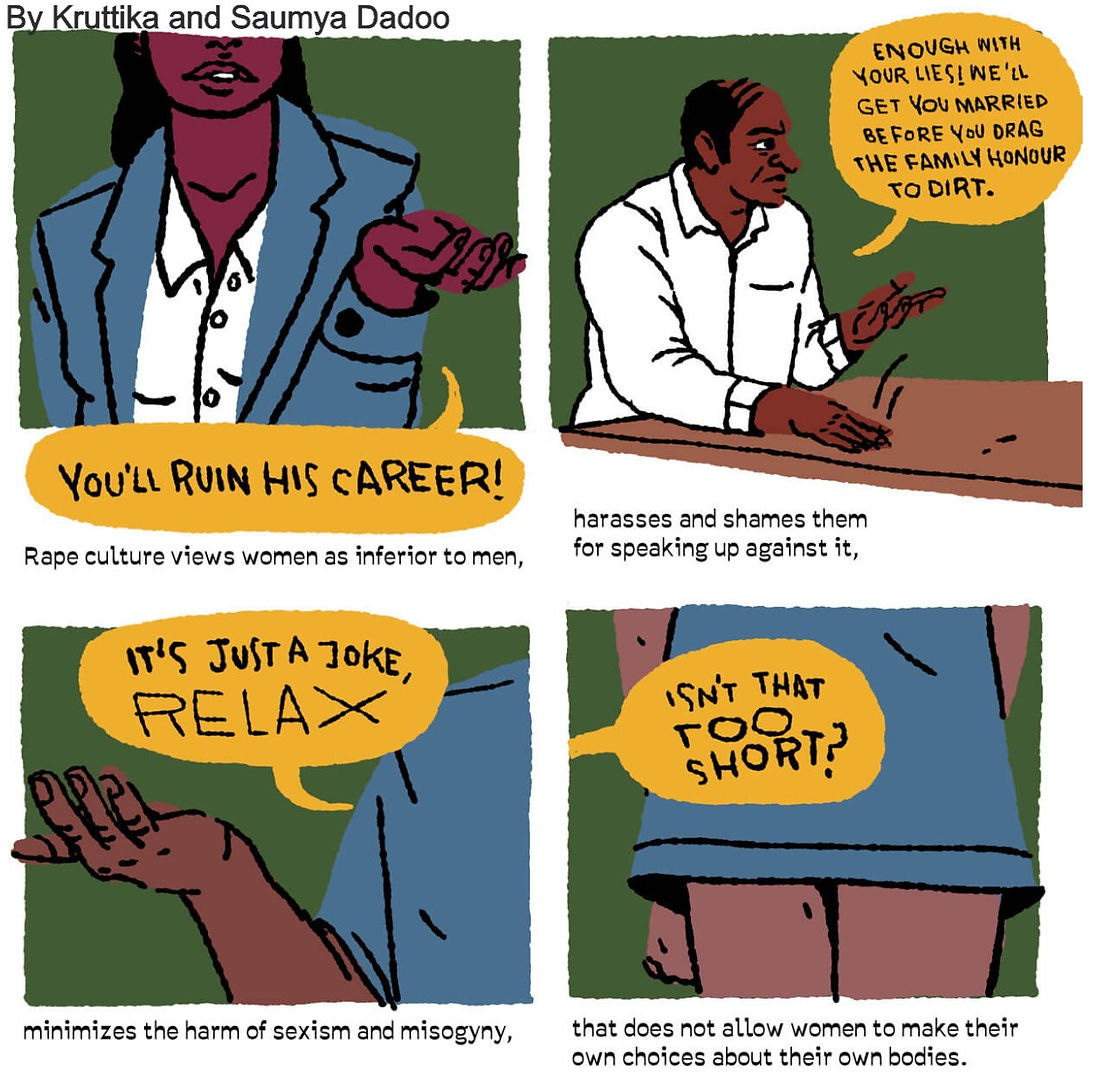

4) Female seclusion inhibits claims-making

Even in countries like India, where women have legal rights, their capacity to challenge challenge male guardians is constrained by social seclusion, patriarchal ideology, and economic insecurity.

In India, women are much less likely to attend or speak at village meetings, let alone make claims on local leaders. Attendance rates range from 25-33% for men and 6-11% for women. It is especially low in areas with tight restrictions on female mobility. In the absence of strong female networks and contentious claims-making, men continue to dominate informal and formal institutions in ways that maintain control over women’s bodies.

Women may not question gender wage gaps, as they presume men to be more competent – as in Pakistan’s garment industry. As Jobeda (a member of a social mobilisation NGO in Bangladesh) explained,

Whatever the village elders said we used to take as the truth. We never protested even though there was a lot of injustice and oppression in the locality. We were afraid of the chairmen, village leaders and members. Moreover, we could not see any reason to protest. After all they were our village leaders, we used to honour them. We thought that to argue with the chairmen was to commit an offence.

52% of Indian women think their husbands are justified in beating their wives under certain circumstances. In Roychowdhury’s sample, the vast majority wanted to remain with their abusers. This is the only way to maintain financial security, social support and feminine virtue.

Growing up, girls learn that the ideal Hindu wife is like Sita, withstanding torture to prove their purity and devotion. A woman virtue lies in being a good wife. Victims of abuse are usually presumed to deserve it. Violence is legitimate to correct ‘failed women’.

“Some women want to remain within their enclosures” Their ‘iccha’ (Bengali for desire) is to stay within the patriarchal ‘gondi’ (enclosure) - explained Dolly (NGO leader).

Brinda’s husband had beaten her, then left her in a house in Kolkata run by a ‘lady’ (possibly a brothel madam). He may have sold her into prostitution. What did she want? To re-unite with her husband.

Shame stains their entire family. Brinda’s parents lied so no one would know that her husband had abandoned her and left her to a brothel. “We won’t be able to show our face” - if people find out (said her mother). Shame discourages legal claims-making.

Brinda was to inherit nothing from her father and didn’t even consider challenging this. She “loved” her brother, acknowledged his inheritance rights, and did not consider her natal home as her own (Rowchowdhury 2021).

Victims may also be terrified of backlash from violent abusers. With so little confidence in justice, they may worry the situation will only become more dangerous.

Indian women are often socialised to sacrifice for the family, and may be relucant to disappoint. Moreover, women may crave their love.

Ashu’s family had greatly invested on her wedding and dowry. Her marriage strengthened their networks. Like many other victims of violence, she expected spousal abuse, but couldn’t bear to shame her kin.

Survivors were often relucant to make claims and humiliate their families. “If I decide to register a case knowing it pains my parents, is that self- esteem or selfishness?” - asked Anshu (Rowchowdhury 2021).

To knowingly disappoint and defy social expectations, one must be willing to be scorned and ostracised. And that’s incredibly difficult in societies where the costs are very severe and so few step out of line.

Given socialisation to be self-sacrificing, stigmatisation of failed marriages, fear of social isolation, loss of parental love, and hostile sexism from the Indian state, the vast majority of Indian victims just want to reconcile.

5) Despondency Traps

If women rarely see successful claims-making or enforcement, they may be caught in what I call “Despondency Traps”. This saps self-efficacy and deters investment in costly battles. Negative feedback loops persist, because almost everyone is pessimistic.

Sadia was in an abusive marriage for 12 years. Never once did she report her husband. She didn’t trust the police and worried reporting would only enrage her husband.

Observing persistent impunity, women wonder ‘What’s the point of complaining?’. The same goes for inheritance – seldom claimed for fear of alienating kin. As a Bangladeshi lawyer explained, ‘There are so many wonderful things… in the national action plan, but when you look in the field it isn’t happening’.

6) Risks of incentivising legal reform

Even if laws are no magic bullet, you may think it’s better to have parity on paper.

Yes, but at what cost?

The international development community has spent decades providing financial incentives for ‘good policies’. Yet it’s questionable whether this has actually led to substantive improvements in state capacity, or just the facade of reform.

TLDR: Laws cannot undo sexism

State capacity remains weak in places with high informality and overburdened criminal justice systems. Even if legal rights exist on paper, they are not necessarily claimed or enforced.

Where precarity is pervasive, families rely heavily on their kin and men guard their honour. In places where females are socialised to submit, vilified for dissent, and economically dependent on male guardians, they tend to endure abuse.

Even if laws are no magic bullet, perhaps it’s a start?

But at what cost?

The international development community has spent decades providing financial incentives for ‘good policies’. Yet it’s questionable whether this has actually led to substantive improvements in state capacity, or just the facade of reform.

What actually works to promote greater gender equality?

Job-creating economic growth and state capacity. This is amply demonstrated by the East Asian Miracle. Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong were once extremely patriarchal, but structural transformation enabled women to seize new economic opportunities, enter the public sphere en masse, and organise to promote gender equality.

I am from India and this post is very good. So what you are trying to say in this and your other articles is that to reduce casteism, sexism and other forms of discrimination, india needs labor intensive economic growth which will give financial independence and power to those oppressed groups to fight against discrimination.

As per Daron Acemoglu in the book “Why Nations Fail”, long term economic growth requires inclusive institutions and for that india has to improve its institutions and make them more inclusive.

Just being a Democracy doesn’t mean the institutions are inclusive.

What do you think india should do to make it’s institutions more inclusive such that it will spur labor intensive economic growth like east asia?

You mentioned working on reducing informal sector in your other post and how the labor laws lead to a lot higher costs for firms to grow beyond 8-10 employees. I really agree with that, but reforming labor laws is very difficult. In india, unions are very politicised and not in a good way, they don’t necessarily have the labor’s best interests in mind.

They are instead used as a political tool. Both the current political party and the Indian national congress have large labor unions and whenever someone tries to reform the archaic laws, they use those labor unions to shut out the reforms to gain short term political capital. Both the parties are guilty of this.

There is also the case where the industrial sector is very crony. Governments and businesses tie up and create laws and situations which are stalling growth, there are also special interest groups who benefit from existing laws and work against any change in those laws.

This seems like an uphill battle, My question is, what are possible solutions for this? How can india make its institutions more inclusive when there are powerful people benefiting from the current institutions and laws?

Another reason to support Robert Lucas' famous quip, "Once you start thinking about economic growth, it is hard to think about anything else."

May you succeed in getting mainstream academia and mainstream NGOs to support improved business environments as a means of improving gender equality.