Generative offer massive gains in productivity, and workplaces are increasingly eager to embrace new technology to maintain competitive advantage. One Australian law firm recently offered a ‘bounty’ of A$20,000 for ideas on how to harness AI. “We’re rolling [the tool] out to the whole firm and the goal is . . . within 12 months, for 80 per cent of the firm to be using it,” explained one partner. Frightened about being left behind, firms want workers who can help them adapt:

“[AI] presents an enormous opportunity for our practice and for all law firms . . . and enormous risks. It’s moving at such an incredible pace that if you don’t start you can get left behind.”

Adoption of Generative AI has been seriously rapid - faster than historical patterns of using personal computers and the internet. It’s all happening very fast.

Yet, women worldwide are 24.6% less likely to use these new powerful technologies. Well-intentioned efforts to prevent plagiarism may amplify these inequalities. A striking study from Norway finds that banning AI creates massive gender gaps in usage, which could jeopardise future earnings.

In this essay, I unpack three new studies on gender differences in adoption of Generative AI, then discuss how academics might provide more inclusive education.

Global Meta-Analysis

Otis and colleagues combine extensive survey analysis, web traffic data, and field experiments. They synthesise data from 16 independent studies surveying over 100,000 individuals across 26 countries. Harnessing Google Scholar, they incorporate all studies that measured both AI use and respondent gender. Samples ranged from U.S. working professionals and Danish workers to global science postdocs and Kenyan entrepreneurs.

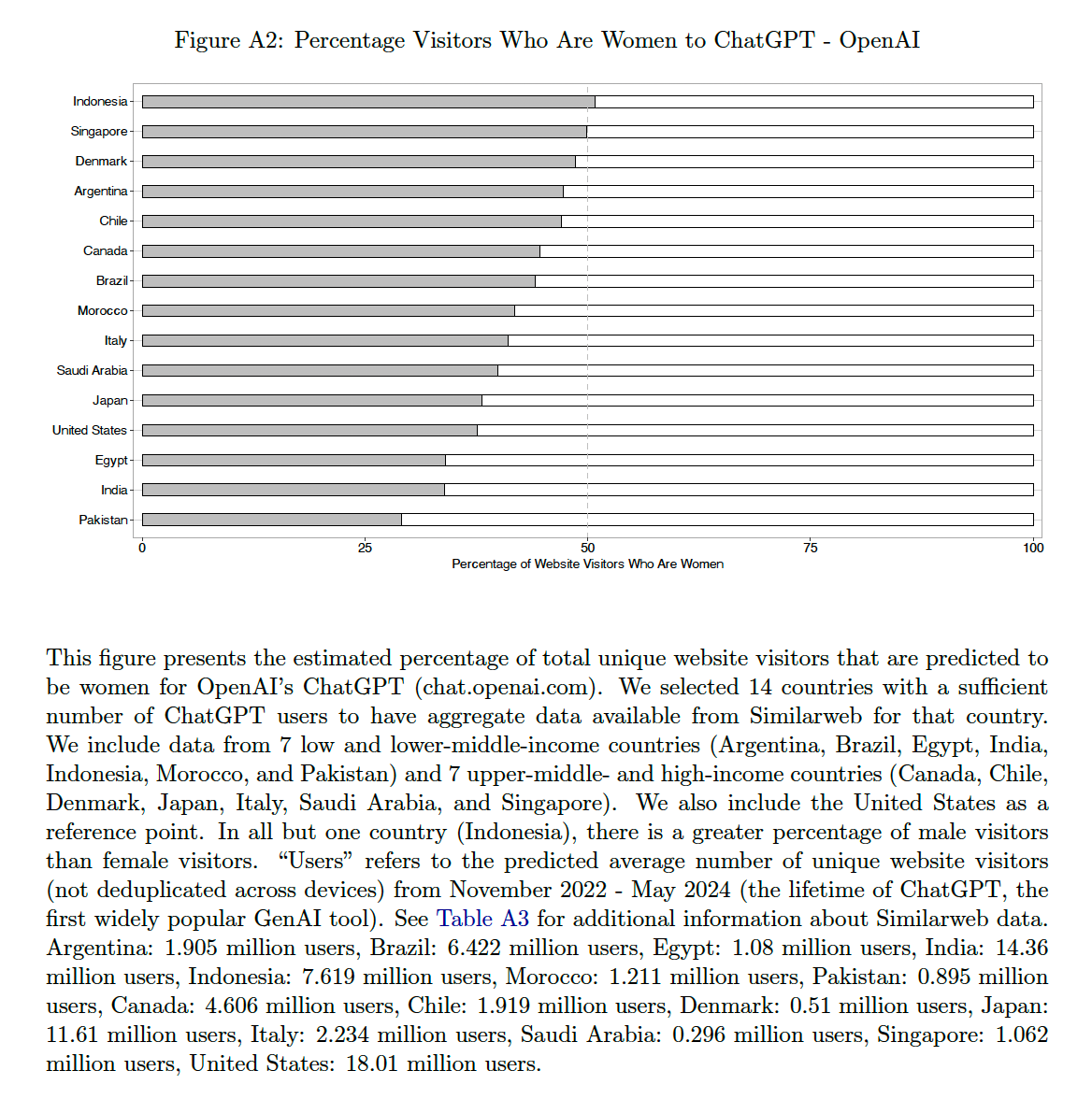

To validate these survey findings with behavioural data, Otis and colleagues analysed web traffic to major AI platforms using Similarweb data. Their analysis covered traffic to prominent platforms from November 2022 through May 2024. This includes 173 million monthly unique visitors to ChatGPT alone, along with 10 million to Midjourney, 7.1 million to Perplexity, and 1.9 million to Anthropic.

To ascertain whether gender gaps might be a function of access, Otis and colleagues ran two field experiments in Kenya:

640 small business entrepreneurs were given access to an AI-powered WhatsApp business mentor.

17,541 Facebook users were offered the opportunity to try ChatGPT.

Women were 24.6% less likely to use AI

This gap persisted across nearly all regions, sectors, and occupations, with only one notable exception: a BCG study of U.S. tech workers showed 3% higher adoption among women, driven primarily by senior women in technical roles.

This pattern was corroborated by web traffic analysis, across low- and high income countries. Women comprised only 42% of ChatGPT users globally, with similar patterns appearing across other platforms: 42.4% of Perplexity users, 39.6% of Midjourney users, and just 31.2% of Anthropic users.

Even when field experiments equalised access, there was a persisted gender gap. Women were 14% less likely to seek AI advice in the WhatsApp experiment, and when offered the opportunity on Facebook women were 12% less likely to use ChatGPT.

What’s the Wider Evidence ?

A comprehensive survey of 100,000 workers in Denmark finds that women are less likely to use ChatGPT even within the same occupations - suggesting the gap isn’t just about industry segregation.

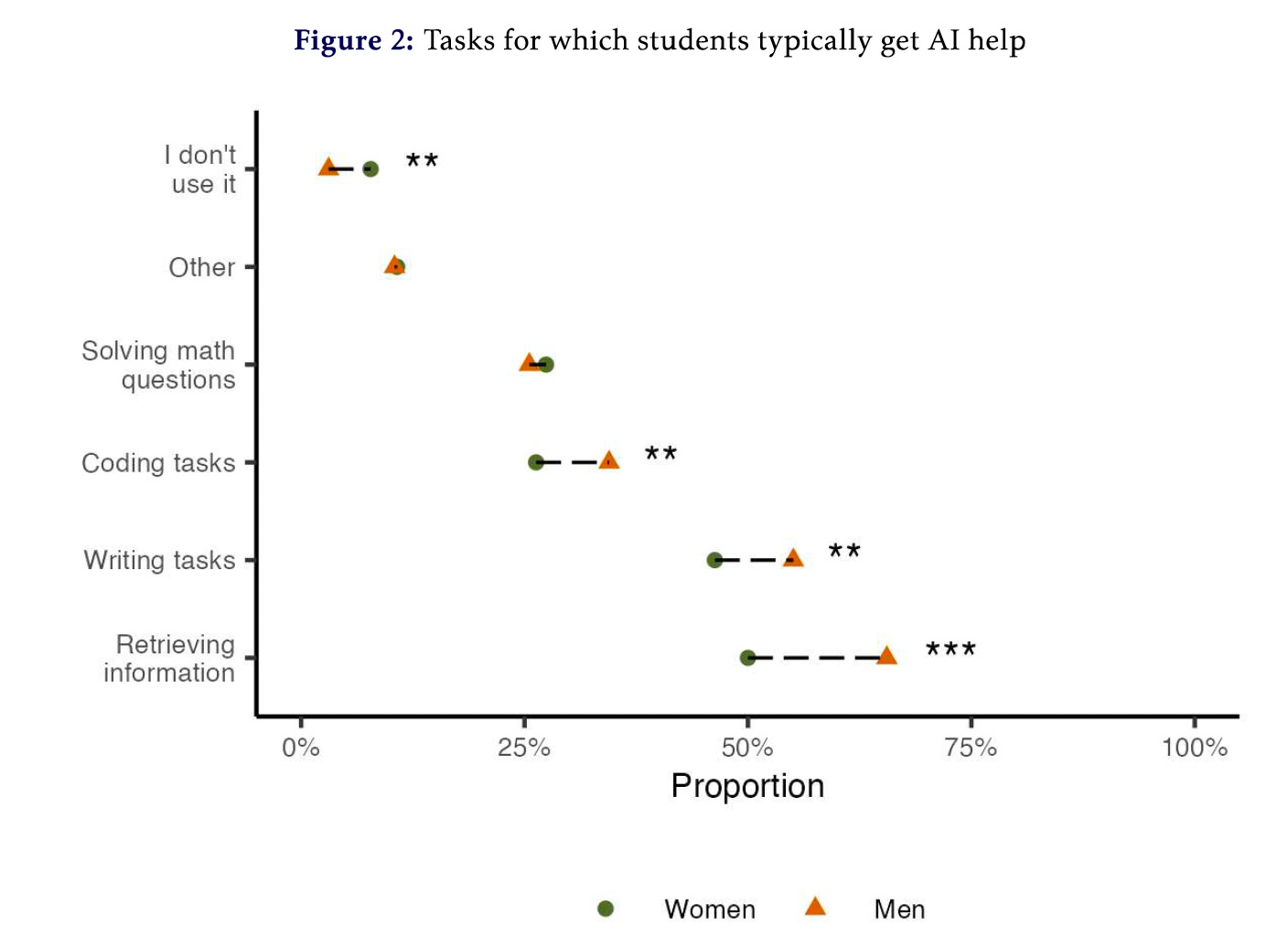

Carvajal, Franco, and Isaksson’s findings from a top Norwegian business school are striking. Female students are 25% less likely to report high use of Generative AI, with high-achieving women being particularly reluctant.

This isn’t just about ability - these women express more skepticism about AI and report less confidence in their prompting skills.

Female students are also less confident in their own prompts, and these attitudes are correlated with success. Self-efficacy predicts persistence, practice and learning.

Bans on AI may compound inequalities

Here’s the most important discovery: banning AI may create a massive gender gap. When AI is permitted, usage intentions are similar - 87% for men and 83% for women. But introduce a ban, and men's drops only modestly to 67% while women's intended usage plummets to 46%.

High-achieving women are especially rule-abiding.

The stakes are high. In a survey of employers, female candidates with AI skills were rated 7.6% higher, with managers overwhelmingly indicating they would promote workers who boost productivity using AI.

When academic policies discourage adoption of the latest technologies, they may inadvertently push women away from skills that increasingly drive workplace success.

Gender differences in college majors

These studies on Generative AI are consistent with the wider literature on the gender pay gap. Today, choice of college major is a major predictor of subsequent earnings. Yet women are less likely to major in STEM fields that ultimately pay more (accounting for 63% of entry-level pay gaps among US college graduates and 51% in Italy). We’re seeing similar self-selection away from productivity-enhancing AI.

How Might Universities Respond?

Vibes shape reality, particularly in universities as incubators of both culture and innovation. If professors portray technology as a threat or taboo, students may internalise that disdain, stunting their AI literacy and proclivity to explore.

Actually, there is a deep irony - academic communities committed to diversity risk reproducing gender inequalities if they demonise AI tools that could help level the playing field.

While broader questions about tech regulation loom, my role as a lecturer is to nurture inclusive education that helps students harness the technological frontier.

I actively demonstrate AI's benefits across the entire student cohort, focusing on building confidence, competence, and technological curiosity. During lectures, we engage with AI tools like Claude in real-time, collaboratively exploring student questions and analysing responses. Students learn to view AI as a writing partner - receiving feedback on drafts and mastering effective prompting techniques.

These hands-on exercises serve dual purposes: normalising AI while sharpening critical thinking. By explicitly welcoming use of AI in assessments, the classroom atmosphere mirrors modern workplace realities, where AI isn’t just permitted but increasingly essential.

My hope? That every student (including women) leave my classroom feeling confident about harnessing these powerful tools, ready to creatively innovate and explore!

I am also curious about the good results you're getting from AI in the classroom. I've had to ban using AI in searches for information during class discussion (I used to love having students look up answers for themselves on search engines) because the answers are wrong--and wrong in unique, bespoke ways for each student, even when identical prompts have been used in ChatGPT. (These are answers to non-controversial fact questions, like "What is the concentration of methicillin that will kill these susceptible bacteria?")

ChatGPT also fabricates references, even when students ask ChatGPT to simply reformat an existing correct reference page into another style. The fabricated references look real, but are amalgamations of author names and article titles form a variety of places, with publication dates, volume, page numbers and DOIs entirely fabricated. Colleagues of mine in university libraries also note that they are seeing the same thing across academic fields.

So, uh, for me personally as a professional woman, I am less likely to use AI because it doesn't work. It makes more work for me because it's so often wrong.

Maybe women have more common sense, and realize AI is hyped beyond its current possibilities.